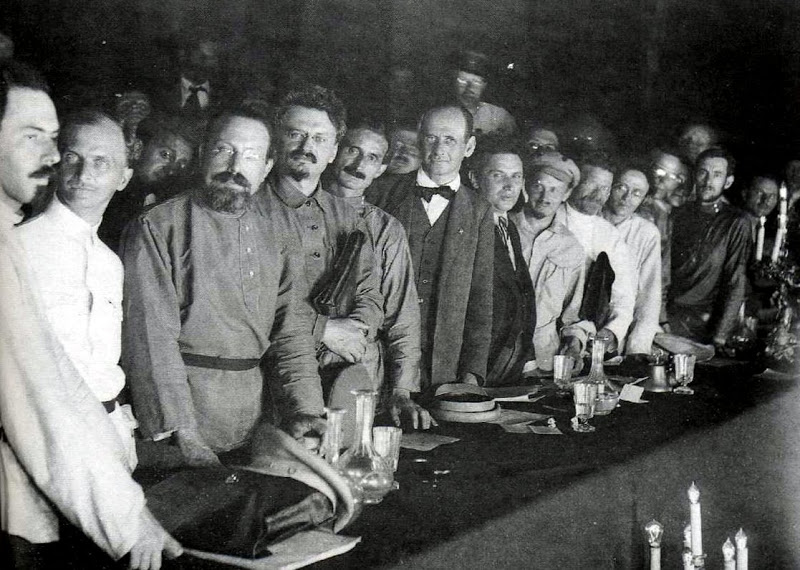

Giacinto Serrati attended the Second Comintern Congress in early 1920, serving on its Presidium and giving this report. A ‘conciliator’, Serrati broke with the Comintern over the Twenty-One Points the following year, to rejoin in 1924. Along with activity in the Italy, Switzerland, and the International, Serrati during his early 1900s sojourn in the U.S. was instrumental in developing Italian Socialist organization here.

‘The Socialist Movement in Italy’ by Giacinto Serrati from Communist International. Vol. 1 No. 13. September, 1920.

A Report to the Executive Committee of the Third International

My report on the Socialist movement in Italy will be very short. The attitude of our Party towards the war from the very beginning is sufficiently well known. Owing to the experience of the Tripolitan war, our Party was not caught unawares by the world war, and it was able to take up the same uncompromising class position which it occupied during the Libyan war. From the very first days we pointed out to the Italian masses the imperialistic nature of the war, and, guided by the resolutions of the Bale Congress, we set ourselves resolutely against it. Not a single vote did the members of our parliamentary group give in favour of the war credits, and all the branches of our Party—there are 2,500 branches in all—never swerved for a single moment in their negative and inimical attitude towards the war. The few members of the Party who showed some hesitation on this question were excluded from the Party, and the only member of the parliamentary group who volunteered for the army and went to the battle front was compelled to leave the ranks of the Party immediately.

Together with the struggle against the war, which we conducted in Italy itself, we undertook a whole series of attempts to revive the proletarian International. Together with the Swiss Socialists, we convened the first International Conference at Lugano (in October, 1914), during which we declared war against war and demanded the convocation of the International Bureau. Later on, together with our Russian comrades, we convened the Zimmerwald and Kienthal Conferences, and carried out in Italy the resolutions passed at these conferences.

We were against all collaboration of the classes, and held strictly to this rule even after the defeat at Caporetto. Our central organ, Avanti, adopted the implacable revolutionary point of view, and never swerved in its attitude, although its circulation fell from 46,000 copies (before the war) to 16,000 copies, and circulation was prohibited in twenty-two provinces. The bourgeoisie attempted to annihilate the paper entirely several times. On May 6, 1919, a band of nationalists assailed the editorial office of the Avanti, devastated the premises, and destroyed the printing machines. In answer to this, the working masses collected among themselves 1,500,000 liras within the space of six months. The circulation of the paper is now 400,000 copies, and it might be even more, were it not for the lack of paper and machinery.

With the suspension of hostilities, the situation in Italy became more complicated and acute. All the factions of the bourgeoisie have now recognised that the war has ended in a general bankruptcy and a complete refutation of the principles, for the realisation of which, according to its partisans, it had been waged. As regards the masses, their irritation and discontent developed from day to day, and the reason for this discontent, as well as the forms in which it was manifested, was not of an economic, but of a social-psychological nature, as evidenced most of all by their unfailing motto : “We do not wish to work for the masters.”

The bourgeoisie, greatly disturbed by such a frame of mind of the masses, strove to pacify them by all possible means. Thus, for instance, a most generous amnesty was proclaimed in Italy, and in a few days parliament will pass a lay on an eight-hour working day. The economic situation, not only of the middle and poorer peasantry, but of the labourers and industrial workers, was improved. The Italian Labour Confederation has established by statistical data that in no other country has the pay for work been raised so high, in comparison with the rise of prices, as in Italy.

Notwithstanding all this, the whole country is flooded by a wave of strikes of a political, rather than economic, nature; and some of them, as, for instance, the strike as a sign of solidarity with Russia, which took place on July 21, 1919, paralysed the whole life of the country. All the workmen and peasants stopped work, including the workers of the government institutions. The railwaymen decided, however, at the last moment not to take part in the strike, because the Italian government, having received a telegraphic message from the French government that the French workers would not participate in the strike, published the telegram in Rome, with the remark that the French workers had betrayed the Italians. After the end of the strike the bourgeoisie, desiring to instill mistrust among the working masses towards the Socialist Party, reproached us for not having made a “revolution.” We were pursuing a completely definite aim; we wished to show by this strike our complete and unreserved solidarity with Russia, without intending at all to carry out a revolution at the moment when this was desired by the bourgeoisie.

Even before July 21, when we went to Paris with Comrade Darragona in order to settle the question of the strike on July 21 with the French Labour Confederation, a strike movement broke out in Italy; the mob devastated the shops, and organised Soviets and factory committees. At present a whole network of such committees is organised in Italy, and the question of their technical and juridicial structure is warmly debated by the Press. Quite recently several factories and mills—metallurgical and textile—have been requisitioned, and one of them was completely under the control of the workers during a whole fortnight, until the capitalists agreed to make concessions and satisfy the demands which had called forth the strike ‘and the requisition of the factories.

In regard to the Russian revolution, the Italian masses are completely on its side. The Russian revolution, its leaders and its representatives, especially Comrade Lenin, are very popular among the masses. The revolutionary movement is maturing everywhere, and rapidly developing in breadth and. depth. We are straining all our efforts in order to render it invincible, to prepare the ground for it and to guarantee its success.

The Labour movement is growing rapidly. The Labour Confederation numbers already 2,000,000 members, out of which 800,000 are peasants. The co-operatives are also increasing, and handing over a share of their profits to their members. Their cash turnover amounts to tens of millions.

The number of members of our Party has grown since the cessation of the war from 42,000 to 165,000; and it must be borne in mind that not one of those who stood for the war or for collaboration of the classes has been received into the Party. In 350 towns the administration is in the hands of Socialists—as, for instance, in Milan, Alexandria, Novarra—and at the forthcoming election the number of towns with Socialist administrations will undoubtedly be increased several times.

The November Congress in Bologna was very important. The Congress revised and supplemented the program of the Party, which was founded in 1892. Since that time the social-political situation in Italy has undergone a radical change. At that time the objects in view were a complete severance from the opportunists and the entrance of the Party into a period of parliamentary struggle; at present the problem is to establish the Communist order by means of the dictatorship of the proletariat. At the Congress of Bologna, the latter idea was upheld by the majority (49,000 votes). Against it were the adherents of Lazzari-Turati, united under the motto, “Unitary Maximalism” (“Massimalismo Unitaria”), supporting the idea of a democratic revolution and repudiating all violence. Lazzari separated from the Communists because the latter insisted upon the inevitableness of violence and the necessity of preparing for the same. The tendency of Bordiga obtained 3,000 votes on two questions: first, regarding boycott of parliament, and, second, regarding the exclusion of Turati, Modigliani, and others from the Party. In regard to the joining of the Third International, the decision to join it was passed unanimously by the whole Congress.

The election campaign throughout Italy bore a clearly-defined class character; its mottoes were: “Struggle against all bourgeois groups,” “For Soviet Russia,” “For the revolution.” One hundred and fifty-eight members of the Socialist Party were elected to Parliament.

This rapid development had also its negative sides; the candidatures were put forward by local organisations. The Central Committee of the Party was not able to control them sufficiently, and, therefore, it is quite possible that some of the new members have proclaimed themselves to be extreme left because of opportunistic considerations only, as otherwise the masses would not have elected them. The first step of the newly-elected group was to elaborate a series of law projects, the carrying out of which is absolutely impossible under the capitalist régime, and the object of which is to show to the masses the impossibility of reconciling the interests of the proletariat with the existence of the old order. Several of the Socialist members were commissioned to draw up programs for the socialisation of the land and similar measures, which are radically inconsistent with the essential principles of the bourgeois order.

In regard to foreign policy, the Party not only demanded the suspension of the blockade, and pronounced itself against all intervention, but from the very first days it insisted on a recognition of Soviet Russia. The results of its insistence are to be seen in the alteration of the attitude of the imperialistic governments, not only of Italy, but of all the countries of the Entente. The new ministry of Giolitti signifies an attempt to establish at least a temporary reconciliation with the working classes. But it will not be successful, because even the extreme Right elements will not agree to coalition with the government. The Party will never allow this. The consequence will probably be new elections, that will lead to new successes of our Party, which is moving undeviatingly towards the realisation of its final aim. Our chief obstacle is a lack of comrades possessing a fuller revolutionary experience, and also a lack of organisation inside the army, into which we are penetrating but slowly. But even in this respect we have started energetic work among the soldiers and officers. Not long ago over 500 former officers—Socialists—met under our auspices.

The letter of Comrade Lenin was of great use to us; it suited our conditions so well that many suspected it had not been written by Lenin, but by us, Italian Socialists. The directions given in this letter correspond completely to our conditions and to the program of our Party. The advice regarding the necessity of a struggle in parliament was the more effective because the opportunist movement in Italy is comparatively strong, and it has its own daily paper with a circulation of 45,000 copies. The Syndicalists (Unione Sindicale) are not the leaders of the working masses—especially now, after the war, during which part of the Syndicalists passed over to the side of the imperialists.

Our Party is marching steadily and consciously to its final aim, which is a Socialist revolution through the dictatorship of the proletariat. We are moving towards this goal continuously, unhesitatingly, consistently, without stopping before anything. The Executive Committee of the Communist International must have full confidence in our Party, which has voluntarily taken the same road as the Committee did: through Zimmerwald and Kienthal to the Third International, regarding which we have fulfilled our duty conscientiously.

SERRATI.

Kremlin, June 19, 1920

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/old_series/v01-n13-1920-CI-grn-goog-r1.pdf