Veteran of the 1905 Revolution, historian, and International Publishers editor Alexander Trachtenberg wrote this substantial introduction on the Paris Commune in the work and thinking of Marx, Engels, and Lenin on the 55th anniversary of the Commune in 1926. The recent efforts of the Marx-Engels Institute in collecting and translating the works of Marx and Engels in the 1920s made this essay, and thousands more, possible for the first time.

‘Marx, Engels and Lenin on the Paris Commune’ by Alexander Trachtenberg from Workers Monthly. Vol. 5 No. 5. March, 1926.

Thirty-five years have passed since the working class population of Paris rose in revolt against a treacherous ruling clique, and with the use of arms established its rule in the city. The epic of that brave struggle has been written in the revolutionary lore of the proletariat, and wherever workers struggle for a free communist society each anniversary of the first conscious revolt against the bourgeoisie is joyously remembered. When the victorious proletarian revolution in Russia was marking red letter days on the Soviet calendar, it remembered the day of the Paris Commune as it did its own November 7th, and March 18th is a legal holiday in the Soviet Union.

The Story of the Commune.

During the war with Prussia (1870-1871), a war through which Napoleon III hoped to bolster up his tottering monarchy, and which Bismark used to mould a united and stronger Germany, the French armies were suffering one defeat after another. The debacle at Sedan sealed the doom of Napoleon’s reign and his monarchy and a provisional government was formed on September 4, 1870. With Paris as the objective of the victorious Prussians, the population armed itself and the National Guard was assuming the command over the defense of the beleaguered city. The Provisional Government ostensibly pledged to wage a defensive war, was in fact making overtures to Bismark, wishing to end the war at all costs. An armistice was signed on Bismark’s terms on January 27, 1871. As a guarantee of France’s observance of the pledges given in its behalf by Thiers, the head of the Provisional Government, the Prussian troops were permitted to occupy the forts surrounding Paris.

The National Assembly elected in February consisted in the main of reactionary elements anxious to make peace with the Prussians and plotting to secure their aid in clearing Paris of revolutionary elements who were gaining ascendancy. At the time when Paris was preparing to defend itself against the invaders, the treacherous government, settled at Versailles, was expediting peace negotiations with the external enemy in order to turn its attention to its foe at home. Having sufficiently humbled France and having inflicted heavy penalties on the French people for Napoleon’s adventurous war, Bismark was ready to accommodate Thiers and keep the Prussian troops near the gates of Paris. While occupying the surrounding forts, the Prussians conveniently kept a section open so that the Versailles troops could harass the Parisians at will.

After failing in previous attempts, Thiers sent during the night of March 18th his regiments to disarm Paris. His particular objective was to take away the artillery which the National Guard kept when the government troops were disarming under the armistice provisions. Thiers, however, miscalculated. The entire working class population rose to the defense of the city. Before the dawn the hired Versailles troops were in retreat from Montmartre and Belleville which they occupied during the night, and the National Guard was in complete control of the situation. There were even defections among the Versailles troops, Generals Lecomte and Thomas being executed by their own soldiers.

During the day the National Guard occupied the various administrative buildings, including the City Hall, and the municipal government of the French capital passed into the hands of the revolutionary Central Committee of the National Guard. Elections were held within a week, and on March 28th, the new city government consisting of 65 revolutionists and only 15 adherents of the National Assembly publicly proclaimed the Commune.

The Commune and the First International.

With bated breath the revolutionary workers of the world, organized then in the International Workingmen’s Association (First International), were watching the unfolding of the Commune.

The heroic struggle on March 18th, the establishment of proletarian dictatorship by the Central Committee of the National Guard was the first attempt at workers’ rule since the foundation of the modern labor movement. Marx took an active interest and was diligently studying the development of events in France and the reaction toward the Paris Commune throughout the world. Although the majority of the Communards were Blanquists and among the minority who were members of the I.W.A. were more Proudhonists than socialists, Marx abstained from open criticism of the activities of the Commune. Marx recognized in the Commune a united front of the various revolutionary groups determined to fight the bourgeoisie and the miserable Thiers’ government. The fraternal sympathy and loyal support of all revolutionists were immediately shown to the Commune. Marx wrote to Varlin and Frankel, members of the Commune and French representatives in the I.W.A.: “I wrote in behalf of your cause several hundred letters to all corners of the world where we have connections. The working class was for the Commune at the start.” The French police accused Marx and the I.W.A. of being responsible for the Commune, and even reproduced “official” instructions to the Paris members to rise against the government. The publication of “Zinoviey letters” and Comintern “plots” in various countries by the minions of capitalist governments are proofs of the old saying that history repeats itself.

The Marx-Kugelman Correspondence.

During the Commune Marx wrote a letter to his friend Dr. Kugelman in Hanover, which Lenin considered one of the greatest revolutionary documents and which he said ought to be reprinted and hung on the wall in the home of every class conscious worker. Outside of the famous “Address of the General Council” which we shall mention later, the letter to Kugelman gives Marx’s reaction to the great revolutionary drama which was being enacted before his eyes. The Marx-Engels correspondence, where so much valuable material on revolutionary tactics is to be found contains no letters regarding the Commune. The last letter to Engels during that period was written on September 16, 1870, and the next on August 29, 1871. During this time Engels was in London and lived near Marx.

In 1907 Lenin edited a Russian translation of Marx’s letters to Kugelman, written between 1862 and 1874 and published by the Neue Zeit in 1902. Kautsky, who was then editor of the famous socialist journal, wrote that the years which the correspondence between Marx and Kugelman covered were “the most important epoch of that period…Lassalle’s agitation, the founding of the International (1864), the appearance of Capital (1867), the first attempt at proletarian dictatorship during the Paris Commune (this Marxist language came naturally to Kautsky in 1902), the break-up of the International caused by the Bakuninists who, defeated at the Hague Congress (1872), have introduced the deadly poison into the organization. At the same time a revolution from above took place, which achieved at least in part, what the bourgeois revolution of 1848 attempted to accomplish—the fall of Austrian absolutism, establishment of a republic in France, unification of Italy, unification of Germany, the incomplete (without Austria).”

Lenin Applies Marx to Russian Revolution.

Lenin considered it important to publish these letters at that time because they contained some opinions of Marx which were applicable to the phase of the revolution which Russian socialism was then experiencing. It was after the defeat of the 1905 Revolution, when the Mensheviks with Plekhanov at the head were considering the Revolution completely defeated.

In an elaborate and brilliant introduction, Lenin takes the letters to Kugelman as a text for his answer to the white-livered socialists who lost all faith in the revolution because the first attempt was not crowned with success: revolutionary theory with revolutionary policy,

“In Russia there is abroad among the socialists a. middle-class conception of Marxism that. that union without which Marxism becomes Brentanism, Struvism, and Sombartism. The doctrine of Marx has combined in one the whole the revolutionary period with its special tasks for the proletariat is an anomaly, while the ‘constitution’, ‘left opposition’ is the rule. In no other country is there now such a revolutionary crisis as in Russia, in no other country are there ‘marxists’ (who belittle and vulgarize Marxism) who take such a sceptical and philistine attitude to the revolution. Because the nature of the revolution is bourgeois, the deduction is made that the bourgeoisie is the driving force of the revolution, while the proletariat has only subsidiary purposes and is not able to lead it.”

On March 3, 1869, Marx wrote Kugelman that the revolutionary movement in France was gaining momentum and that “the Parisians are beginning seriously to study their recent revolutionary past and to get ready for the newly approaching revolutionary struggle.” Lenin calls particular attention to Marx’s ability to feel the pulse of the epoch, and during peaceful times foresee approaching revolutionary crises,

“Pedants of Marxism,” writes Lenin, “believe this is ethical nonsense, romanticism, absence of realism. No, gentlemen, this is a union of theory and practice of the class struggle.”

On December 13, 1870, Marx wrote Kugelman, among other things, the following prophetic words: “Whatever the outcome of the war, it has taught the French workers the use of arms, and this makes the future more hopeful.” Three months before the Paris uprising Marx was already smelling powder, and foresaw the approaching crisis.

Marx Writes Kugelman on the Commune.

The celebrated letter to Kugelman which Marx wrote on April 12, 1871, during the height of the Commune, and which Lenin considers the crowning letter of the entire collection, began as follows:

“If you will turn to the last chapter of the 18th Brumaire you will see that according to my opinion the next revolutionary uprising in France will be an attempt to destroy the bureaucratic military machine instead of handing it over from one group to the other as was done previously. Such indeed is the preliminary condition of every genuinely popular revolution on the continent. This is exactly the attempt of our heroic Paris comrades. What dexterity, what historical initiative, what ability for self sacrifice these Parisians display. After six months of starvation and destruction caused more by internal treachery than by the foreign enemy, they rise under Prussian bayonets as tho there was no war between France and Germany, as tho the enemy wasn’t still at the gates of Paris. History records no such example of heroism. If they will be defeated it will be because of their ‘magnanimity’. They should have immediately marched on Versailles, as soon as Vinay and the reactionary portion of the Paris National Guard escaped from Paris. The opportune moment was missed on account of ‘conscientiousness’. They did not want to start a civil war, as if the monstrosity Thiers hadn’t already begun it with his attempt to disarm Paris.”

Marx, the revolutionary strategist, knew that when the enemy of revolutionary Paris was on the run, it was the job of the National Guard to pursue Thiers’ defeated army until it was annihilated, rather than allow it time to reorganize its forces and return to fight the Paris workers. Remembering Plekhanov’s famous admonition after the failure of the December, 1905 uprising in Moscow— “They shouldn’t have resorted to arms”—Lenin recalls that Marx warned the Parisian workers in September, 1870, when the Blanquists were bent upon the overthrow of the bourgeois government against unprepared uprisings. (In a letter to Engels in August, 1870, Marx expressed his doubt regarding a favorable revolutionary situation in France, while German troops were surrounding Paris.)

“But how did Marx act when what he warned against what took place in March, 1871? Has he used it against his opponents—the Blanquists and Proudhonists who were leading the Commune? Has he like a school ma’am kept on repeating: I told you so, I warned you. Here you have your romancing, your revolutionary dreams. Perhaps he criticised the Communards as Plekhanov did the December fighters with a self-satisfied philistine reproach: “They shouldn’t have resorted to arms? Marx considered an uprising in September, 1870, an insanity. Seeing a mass uprising in April, 1871, he gave the full attention of a participant in the great occurrences, which marked a step forward in the historic revolutionary movement.”

In the second part of his letter to Kugelman, Marx mentions another grave error in the early history of the Commune: “The Central Committee (of the National Guard) relinquished its powers too soon to pass them on to the Commune. Again on account of ‘honesty’ carried to suspicion. Be it as it may, this Paris uprising, even if it will be suppressed by the wolves, swine and dirty dogs of the old order, is the most glorious achievement of our party* since the June uprising. Compare these Parisians, ready to storm the heavens, with hangers-on of the German-Prussian holy Roman empire with its antediluvian mascarades reeking with the smell of the barracks, church, junkerdom, and especially philistinism.”

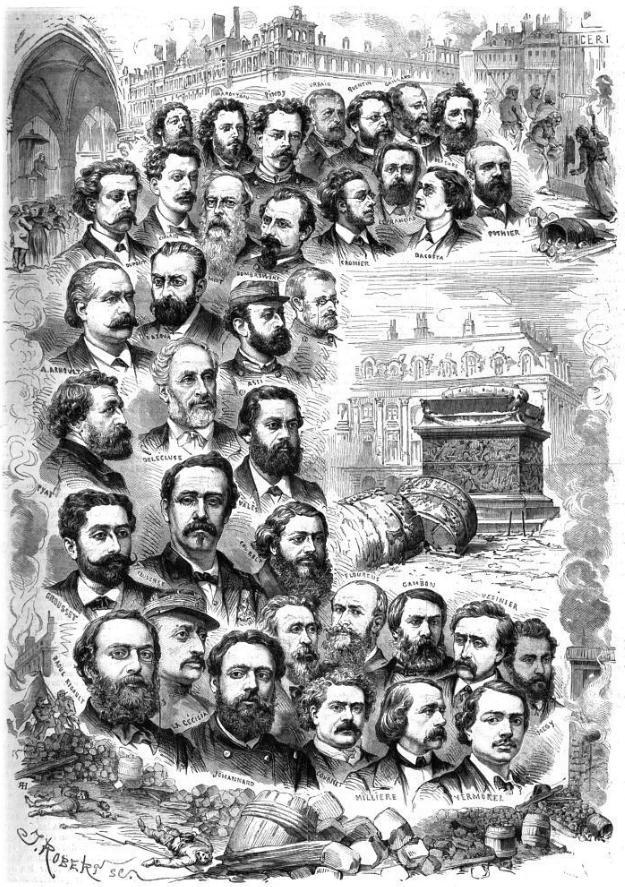

(*Although the majority of the leaders of the Commune were not followers of the I. W. A., yet the influence of the I. W. A, and Marx among the Paris workers was marked. Among the leaders were Varlin, Frankel, Longuet, Vaillant, Pottier, Dupont, Duval, Theiss and other members of the First International. A.T.)

Here again Marx, the centralist, realized that a successful revolutionary struggle against Thiers could have been carried out by the Paris workers only under the leadership of a centralized revolutionary authority which had the military resources at its command. This centralized authority was then the Central Committee of the National Guard. By renouncing its powers and turning over its authority to the loosely organized Commune, the National Guard dissipated the revolutionary energy of its armed forces.

Five days later, April 17, Marx writes Kugelman again about the Commune. He takes issue with his friend who seemed to have compared the Paris rising to the protest demonstrations which took place in June, 1849, and which were of a petty bourgeois origin. Kugelman must have been questioning the wisdom of the revolt and showed his skepticism regarding its outcome. “To create world history would be, of course, very easy if the struggle could be waged only under absolutely favorable circumstances,” was Marx’s caustic repartee.

After saying that other circumstances are also possible and these must be taken into consideration, Marx declared that in the case of the Commune “the decisive unfavorable circumstance must be sought, not in the general conditions of French society, but in the presence of Prussians at the very gates of Paris. “This,” he continued, “the bourgeois scoundrels of Versailles knew. That is why they put before the Parisians the alternative: either to accept the provoked struggle or to capitulate without a fight. The demoralization of the working class which would ensue as a result of the second instance would be a greater misfortune than the loss of any number of leaders. The struggle of the working class against the capitalist class and the state representing its interests, has, thanks to the Paris Commune, entered a new phase. However it may end this time, a new landmark of universal historical significance has been achieved just the same.”

This was precisely Lenin’s attitude regarding the December uprising in Moscow in 1905. The revolutionists of Moscow who had the support of the masses either had to accept the provocation of the Czar’s troops or go down in moral defeat before the Moscow workers. Tho defeated after a hard fought battle, the revolutionists came out of that unequal struggle glorified by the entire working class of Russia.

While the panicky Mensheviks were mumbling the Plekhanov formula: “They should not have resorted to arms,” Lenin saw in the heroic struggle of the Moscow workers the revolutionary will to conquer of the Russian working class as a whole.

Commenting on Marx’s observation that the Paris workers had to take up the fight, Lenin wrote: “Marx could appreciate that there were moments in history when a struggle of the masses, even in a hopeless cause, was necessary, for the sake of the future education of these masses and their training for the next struggle.”

It was this hopeful view of the Paris uprising applied to the revolutionary struggle of 1905 that led Lenin to maintain in his introduction to the collection of the Kugelman letters in 1907, when dark reaction was the order of the day in Russia: “The working class of Russia has already demonstrated once and will prove again that it is able to ‘storm the heavens’.”

And it did in 1917.

The Counter-Revolution Triumphs.

The Commune existed only two months. During this time it showed, according to Engels, its class character in most of the administrative acts. Among the social achievements of the Commune must be mentioned: the reorganization of the army to make it serve the interests of the Commune; the separation of the Church and State; removal of religious control over public education; abolition of night work in the bakeries; limitation of the payment of officials to not more than worker’s wages; abolition of fines levied upon workers; and granting the workers the right to operate the shops and factories deserted or closed by their owners.

Writing on the 40th anniversary of the Commune, Lenin made the following elementary Marxian observation: “In modern society the proletariat, enslaved by capital economically, cannot rule politically before breaking the chains which bind it to capital. This is why the Commune had to develop along socialist lines, that is, to attempt to overthrow the rule of the bourgeoisie, the rule of capital, the destruction of the very foundations of the present social order.”

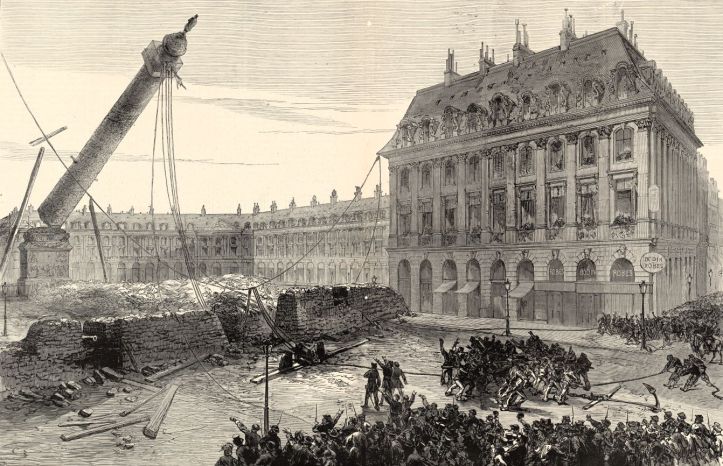

Cut off from the rest of the country, and having lost strategic opportunities at the beginning, the Communards were soon to fight for their very lives. Thiers reorganized his forces at Versailles. With the aid of soldiers hurriedly returned from the German camps and the benevolent attitude of the Prussian troops, he was able to marshall new forces and make war on Paris. Thiers’ troops were permitted by the Prussians to concentrate around the city. The Commune allowed it to go undefended, except the eastern part which was inhabited by the working class population. From May 21 to 28 the city was subjected to a bombardment by Thiers’ avenging hordes. The Paris workers retired to their quarters, fought like lions to defend the Commune. The counter-revolution showed no mercy. Fighting against odds the Commune fell amid ruin and destruction, brought by the Versailles army. As a result of a week’s fighting thousands lay prostrate in the streets, more thousands of captives were taken to the Pere la Chaise cemetery where they were slaughtered in groups and many more were exiled to penal colonies.

Marx’s Epic on the Commune.

The first attempt at proletarian dictatorship was short lived. The heroic struggles of the Paris workers, the actual achievements and potential possibilities of the Commune, have since been the subject of wonder and study by the revolutionary movement of the world. The first to come forward with a complete analysis of what had happened in Paris was, of course, Marx himself. The blood of the Parisian workers, spilled in the course of proletarian emancipation hadn’t dried when Marx read to the General Council of the I.W.A. a paper which was destined to become one of the greatest pieces of political writing ever penned. Two days after the fall of the Commune, May 30, Marx read his famous “Address” which later became known under the title “The Civil War in France.” From a letter to Professor Beesly on June 12, we learn that the “Address” was more than twice as long as was published.

When the Address was published in June, 1871, the authorship was not given. The names of the members of the General Council were affixed to the document. Marx was forced however, soon to announce himself as the author because of the attacks in the bourgeois press. In a letter to Kugelman, June 18, Marx writes: “Now, this manifesto, which you will soon receive, is creating a devilish excitement, and I have the honor to be at this moment the man who is vilified and threatened more than any one else in London. This is, really, fine— after twenty years of a muddy idyll! The government organ, The Observer, threatens me with court proceedings. Let them try. I dare the canaille!”

Marx wrote “The Civil War in France” to meet the attacks upon the Commune from the bourgeois and reformist ranks. In true Marx fashion he drew a picture of the forces which brought it about and hurled his invectives against the bourgeoisie and its agents. He knew that all crimes in existence would be charged against the Paris workers, just as the Bolsheviks were accused of all crimes which could be conjured up by the morbid mind. He unmasked the enemies of the Commune before they had a chance to speak. He also had in mind the faint-hearted, the ‘I told you so’ revolutionists, when he analyzed the conditions under which the Commune had to work and glorified the heroism and revolutionary self sacrifice of the proletarian workers of Paris. “The Civil War in France” will forever remain a literary communist landmark because one sees in it not only Marx the theoretician, but also the herald of the people, the fighter, the revolutionary strategist, the enthusiastic leader, the defender of his class against any and all enemies.

The Commune made mistakes. Marx was accused of taking the Commune with its mistakes under the protecting wing of the I.W.A. But Marx knew of these mistakes. He wrote to Frankel and Varlin in the letter referred to above on May 13: “The Commune, it seems to me, is spending too much time on small matters and personal frictions. Evidently other influences besides proletarian are at work. All this will not amount to much if you could only make up for the lost time.” There were grave errors mentioned by Marx in his letter to Kugelman referred to above. Marx wrote about the fatal mistake of the Commune in not fortifying Paris both against Versailles and the Prussians; leaving undefended the Montmartre heights in the north was, he thought, particularly playing into the hands of the enemy.

Marx’s “Address” does not deal with the details of the Commune. It was written too soon to give a review of what had actually occurred between March 18 and May 28. This was done by others in special studies of the Commune published later. Marx began his “Address” with a masterful analysis of the brigand crew which took control of France after the monarchy fell.

Thiers and every one of his accomplices are closely scrutinized, their treacherous dealings with Bismark revealed, and their political chicanery exposed. Marx shows how armed proletarian Paris stood in the way of their schemes and that is why the “pacification” of Paris had to be accomplished at all costs. The gauntlet was thrown by the invading mercenaries of Versailles and all Paris rose to the defense of the city. “The glorious workingmen’s revolution of March 18 held undisputed sway of Paris. The Central Committee (of the National Guard) was its provisional government. Europe seemed, for a moment, to doubt whether its recent sensational performances of state and war had any reality in them, or whether they were the dreams of a long bygone past.”

Marx testified to the absence of acts of violence after March 18th. While Thiers was crying out about the execution of two of his generals by the Communards, Marx tells how General Lecomte, who led one of the attacking regiments, came to his end. The general ordered his soldiers to fire on an unarmed gathering, and, when the soldiers refused, he insulted them. Instead of shooting women and children, his own men shot him. “The inveterate habits acquired by the soldiery under the training of the enemies of the working class, are, of course, not likely to change the very moment these soldiers change sides.” While the Commune would not use terror, —‘‘the magnanimity of armed workingmen”’—the Communards taken as prisoners to Versailles were tortured and executed without trial by Gallifet.

Marx and Engels on the State.

“The Civil War in France” is great revolutionary classic. The third part of it is particularly replete with passages which will always remain guideposts for the student and active worker in the Communist movement. It is here that we find analyzed the most important contribution of the Commune. At the very beginning of this section we come across the famous passage which was used the following year by Marx and Engels in an introduction to a new edition of the Communist Manifesto and which they considered as an important amendment of the Manifesto, Marx asks: “What is the Commune, that sphinx so tantalizing to the bourgeois mind?” He answers by quoting from the proclamation of the Central Committee on March 18: “The proletarians of Paris, amidst the failures and treasons of the ruling class, have understood that the hour has struck for them to save the situation by taking over into their own hands the direction of public affairs. They have understood that it is their imperious duty and their absolute right to render themselves masters of their own destinies, by seizing upon the governmental power.” Then follows Marx’s historic comment: “But the working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready made State machinery and wield it for its own purposes.” It was this theme and Marx’s discussion of the origin and development of the bourgeois State which served Lenin as text for his “State and Revolution.” Readers of that important study of the State, “the problem of all problems” according to Bukharin, will find profuse quotations from this part of “The Civil War in France.” It should be remembered that already on April 12th, in his letter to Kugelman, Marx spoke about “the destruction of the bureaucratic political machine,” as a prerequisite of a real popular revolution.

In 1891, the 20th anniversary of the Commune, Engels wrote an introduction to a new German edition of “The Civil War in France.” (The available English translation of the pamphlet has only part of that introduction. The reason for the omission of the second part is not given. Whether his omission was an act of vandalism or of ignorance, the writer is not prepared at present to venture an opinion). In criticising the Commune for not taking over the Bank of France and using it for its own advantage, Engels points out that the Commune tried to utilize the old government apparatus. He comes back to what Marx took up in his “Address” by asserting that “the Commune should have recognized that the workers, having assumed power, cannot rule with the old State power, the machinery used before for its own exploitation.” Engels concludes: “In truth, the State is nothing but an apparatus for the oppression of one class by another, in a democratic republic not less than in a monarchy.”

Here is Marx’s analysis of the nature of the State in capitalist society. “At the same pace at which the progress of modern industry developed, widened, intensified the class antagonism between capital and labor, the State power assumed more and more the character of the national power of capital over labor, a public force organized for social enslavement, an engine of class despotism. After every revolution, marking a progressive phase in the class struggle, the purely repressive character of the State power stands out in bolder and bolder relief.”

And further again, after analyzing the results of the various revolutions from 1830 to 1871, Marx concludes on the nature of the capitalist State: ‘“Democracy is, at the same time, the most prostitute and the ultimate form of the State which nascent middleclass society had commenced to elaborate as a means of its own emancipation from feudalism, and which full-grown bourgeois society had finally transformed into a means for the enslavement of labor by capital.” The Commune, according to Marx, “was not only to supersede the monarchical form of class rule, but class rule itself.” The different measures of the Commune were aimed at the very foundations of bourgeois rule. It was “to serve as a lever for uprooting the economical foundations upon which rests the existence of classes and therefore class rule. With labor emancipated, every man becomes a working man and productive labor ceases to be a class attribute.” Marx saw in the Commune not merely a revolt, not only an experiment. He saw in it a proletarian dictatorship exercising the will of the working class to abolish these forms which made class rule possible.

Speaking about those who usually prattle of the emancipation of labor until labor really begins to emancipate itself, Marx says: “The Commune, they exclaim, intends to abolish property, the basis of all civilization! Yes, gentlemen, the Commune intended to abolish the class property which makes the labor of many the wealth of the few. It aimed at the expropriation of the expropriators. But this is Communism, ‘impossible’ Communism!”

Marx shows that the middle classes had everything to gain from the Commune, and in fact, the Paris petty bourgeoisie benefited by the legislation regarding the moratorium on debts and the payments of rentals. Similarly, in the case of the peasants, Marx declares that the Commune was perfectly right in telling the peasants that “its victory was their only hope.”

Marx on “National Defense.”

Marx speaks of the last stand of the Paris workers, who fought against terrific odds. He shows how their defeat was accomplished under Bismarck’s patronage. The fact that they were but recently enemies did not prevent the Prussians from helping Thiers in his murderous work. Marx was moved to make the following observation on the nature of nationalism and war, after witnessing the cooperation of the German militarists and French reactionaries in their onslaught on the Commune:

“The highest heroic effort of which old society is still capable is national war: and it is now proved to be a mere governmental humbug, intended to defer the struggle of the classes thrown aside as soon as that class struggle bursts out in civil war. Class rule is no longer able to disguise itself in a national uniform; the national governments are one as against the proletariat.”

How many socialist parties of the warring nations remembered this passage in August, 1914. Plekhanov called upon the Russian socialists to fight against Prussianism. Scheidemann and Ebert yelled about the Russian Cossacks, threatening the “free” institutions of Germany. Renaudel and Vandervelde exhorted the French and Belgian workers to defend the fatherland in the name of democracy and national interest. Henderson did the same in England, and Spargo in America. A class peace was demanded so that the workers and capitalists might all unite to fight their “common” enemy. Only the Russian Bolsheviks and minorities in the various socialist parties did not surrender their socialism and refused to fall a prey to this apostasy. The social-patriotic parties during the war have continued their class peace after the war and are today the stone around the neck of the workers who still follow them.”

The Commune—the First Proletarian Revolution.

The Commune is the great tradition of the French working class. The mute walls of Pere la Chaise remind the French workers of the heroism of their proletarian fathers who fought for freedom from wage slavery. The Commune is also the heritage of the entire proletariat. It was the first revolution with the workers not only fighting in it but also controlling and directing it towards proletarian aims. As Lenin wrote in 1908: “The Commune taught the European workers to consider concretely the question of the social revolution.”

The Commune is one of the brightest jewels in the workers’ revolutionary diadem. Marx’s tribute at the close of his historic Address testifies to the fealty of the world’s proletariat to the memory of the valiant Communards and to the cause in behalf of which they fought: “Workingmen’s Paris, with its Commune, will be forever celebrated as the glorious harbinger of the new society. Its martyrs are enshrined in the great heart of the working class. Its exterminators history has already nailed to that pillory from which all the prayers of their priests will not avail to redeem them.”

Engels on the Commune as a Dictatorship.

The Commune was the first attempt at proletarian dictatorship. It was not victorious but it was the prototype of the lasting dictatorship inaugurated by the Russian workers forty-six years afterwards. The socialists, wedded to bourgeois democracy, claim that the founders of scientific socialism did not favor proletarian dictatorship and that only the “Byzantine” Bolsheviks introduced it into the Marxian lexicon. Engels’ introduction to “The Civil War in France” written in 1891, closes with the following passage: “The German philistine (read ‘socialist’—A.T.) has recently been possessed of a wholesome fear for the phrase: dictatorship of the proletariat. Well then, gentlemen, do you want to know what this dictatorship is like? Look at the Paris Commune! This was the dictatorship of the proletariat!”

Engels was the revolutionist par excellence. He lived in the spirit of a revolutionist to his old age. When he wrote the above quoted passage he was over seventy years old. Several years before, the day following Marx’s death, Engels wrote to his and Marx’s friend and comrade, Johann Philip Becker: “Now we are almost the only ones left of the old 1848 guard. Well, then, we shall remain on the barricades. Let the bullets fly, friends fall, it will not surprise us. If a bullet will get one of us, let us hope that it will strike well so one wouldn’t have to linger long.”

The Commune is Immortal.

From among the second generation of Marxists, it was Lenin more than anyone else who analyzed the lessons of the Commune. Kautsky, who has done a great deal to popularize Marx (which didn’t prevent him later from disowning him) neglected the Commune. Lenin saw in the Commune the birth of the methods which the workers will have to use in the struggle for their emancipation. In his article on the 40th anniversary of the Commune, quoted above, he summarizes as follows his evaluation of the historic significance of the Commune: “The cause of the Commune is the cause of the social revolution, the cause of the complete political and economic liberation of the workers; it is the cause of the world’s proletariat. In this sense it is immortal.”

Some twenty years ago a translation of a French pamphlet on the Commune was popular in the Russian revolutionary movement. It opened with the following words: “Uncover your heads, for I shall speak about the martyrs of the Commune.”

March is a month which is replete with days of remembrance for the revolutionist. “March days” include the barricade struggles during 1848 as well as the establishment of the Commune in 1871. March 14, 1883, is the day of Marx’s death, which to Engels meant that “Humanity became shorter by a head.” March 2, 1919, is the day when the Communist International was founded.

We shall think on this 55th anniversary of the Commune about the brave Communards but the best way to revere the memory of the dead at Pere la Chaise is to rededicate ourselves to the cause in which they heroically fought and for which they gloriously gave their lives.

The Workers Monthly began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Party publication. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and the Communist Party began publishing The Communist as its theoretical magazine. Editors included Earl Browder and Max Bedacht as the magazine continued the Liberator’s use of graphics and art.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/wm/1926/v5n05-mar-1926-1B-WM.pdf