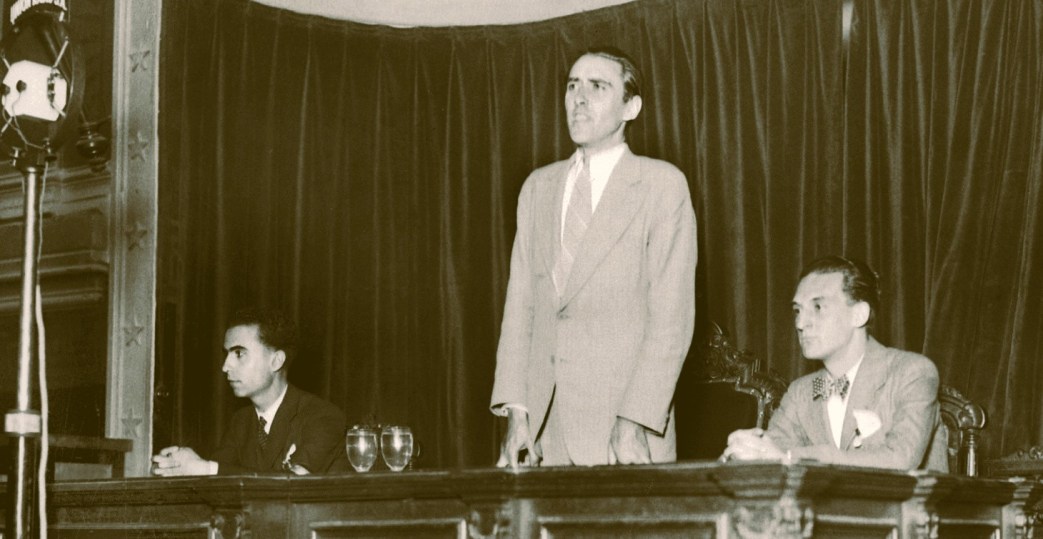

The P.O.U.M.’s Secretary Joaquín Maurin offers the Party’s outlook just before the victory of the Popular Front in May, 1936. Maurin is an exemplary figure in illuminating the larger, fluid, dynamic of syndicalist-Bolshevik debates and relations that would define first period of the Comintern. A CNT militant who became formative in developing Spain’s’ Communist movement, emerged at the central leader of the 1920s Spanish C.P. Later Maurin would align with the so-called ‘Right Opposition,’ forming the Workers and Peasants Bloc in 1931. That Bloc would unite Andreu Nin’s Left Opposition to establish the P.O.U.M. in 1935, in what was an almost unique fusion between ‘Right’ and ‘Left Oppositions’ to the Stalinist leadership of the International. That unity was based on rejection of the Comintern’s Popular Front conception of Spain entering a bourgeois revolution. The document below was written just before the Front’s victory, which the P.O.U.M. supported and participated in in Catalonia, and before Maurin’s arrest (the introduction wrongly says he was killed) at the beginning of the fascist rising in July. Maurin would spend the entire war in prison.

‘Perspectives for Spanish Revolution’ by Joaquín Maurín from International Class Struggle (I.C.O.). Vol, 1 No. 2. Winter, 1936.

The author of the article printed below is the widely known Spanish Communist leader Joaquin Maurin, recently captured and executed by General Mola’s butchers, on the Aragon front.

Maurin was expelled from the Communist International during the ultra-left drive in 1930 and immediately set about building his organization of opposition communists. He secured a large measure of success in Catalonia where he was very well known and greatly respected. Towards the end of 1935 Maurin’s organization merged with the group led by the capable and internationally known Andres Nin who had completely broken with Trotsky and Trotskyism. Thus was born the Workers Party of Marxist Unity (P.O.U.M.) which has established for itself a sterling reputation in the fighting on the Aragon front and in the Asturias.

Joaquin Maurin’s position, as also the present position of the P.O.U.M. in the bitter struggle against fascism in Spain is, in the main, identical with the position of the International Communist Opposition. In recognition of this agreement many contingents of German Communist Oppositionists offered their services and were welcomed into the fighting ranks of the P.O.U.M.

Maurin took an active part in the revolution of October 1934 and after the final defeat of the Asturian miners he was forced to go into hiding because the government had placed a price on his head. It was during this period that he wrote a series of five articles on the October revolt, under the pseudonym of Juan Antonio, especially for the Workers Age. A perusal of these articles will indicate what a keen political observer Maurin was. (See Workers Age of Feb. 9, 16 and 23, and March 2 and 9, 1935.)

The present article was first published in May 1936 in the Nueva Era, as a refutation of the contention of the Communist and Socialist Parties that the Spanish Revolution must not be permitted to go beyond the bourgeois-democratic stage. We submit it here in slightly abbreviated form, due to space limitations. Written fully two months before the fascist revolt, Maurin nevertheless foresaw with great clarity the course which events would take. His criticism of the People’s Front, the accuracy with which he forecasts the bid of the fascists for power and the ultimate role of the Azana Republicans, marks him as a leader of great ability.

There is little doubt that in the present confusion in the working class movement in Spain, the P.O.U.M. stands out as the only Marxist organization. The execution of Maurin was a tremendous loss to the P.O.U.M. and the Spanish proletariat and to the revolutionary movement thruout the world. Editor.

THE STALINIST communists, in practice ex-communists, affirm that our revolution is bourgeois-democratic in nature. This has extraordinarily grave political consequences. It signifies placing the proletariat in a secondary place, fulfilling the role of running footman of the bourgeoisie.

The socialists continue navigating in the midst of a sea of confusion and of a complete lack of theoretical outlook. Fundamentally, they also believe–and act accordingly–that the revolution is bourgeois-democratic. This theoretical position, and the consequent tactics of the Communist and Socialist Parties, are the principal cause for the slowness of the revolutionary process.

Opposed to the socialists and Stalinists there is a Marxist sector, ours, which begins with the supposition that we are in the presence, not of a bourgeois-democratic revolution, but of a socialist-democratic revolution, or to be more exact, a socialist revolution.

The bourgeoisie was a revolutionary class only when, after its birth in the course of the Middle Ages and especially during the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, it fought against feudalism and the church.

The bourgeoisie, after a series of centennial combats which at times acquired an epic splendor–the English and French revolutions–conquered political power in a great number of countries. The bourgeoisie then organized an economic system: capitalism. Now then, in the same manner as from the loins of ancient feudalism a new social class was born–the bourgeoisie–whose mission it was to destroy feudalism, so also from the loins of capitalism arose the proletariat, whose historic mission it was to be the heir, continuer and destroyer, at the same time, of the bourgeoisie. The bourgeoisie, a revolutionary class in relation to feudalism, has been transformed into a conservative and reactionary class with respect to the proletariat. This transformation of the bourgeoisie begins to manifest itself on the one hand, as feudalism is destroyed, and, on the other hand, as the working class develops in the heat of the factory system and large industry. This change is observed experimentally in 1848, attaining in 1871, in the French Commune, gigantic proportions. This evolution of the bourgeoisie in a retrograde sense, in opposition to the growth and revolutionary development of the proletariat, is accentuated more and more during the 20th century, the epoch of imperialism.

The first revolution in the 20th century is that of Russia, in 1905. Even in Russia where it had to liquidate feudalism, it was palpably demonstrated that the bourgeoisie was no longer a revolutionary force, that the only truly progressive class was the proletariat. Only the proletariat could carry the revolution forward. The lack of a true revolutionary party capable of fulfilling the functions of an axis of the proletariat and find allies, principally the peasantry, determined the failure of the revolution. The bourgeoisie, after some vacillations, ended up by allying itself with feudal Czarism against the working class.

In 1917 the problem is posed again, as in 1905. But the workers’ movement has before it the experience of twelve years ago. While reformist socialism, menshevism, pretends that the Russian revolution is a bourgeois one, revolutionary Marxism believes that the proletariat must conquer political power to fulfill the bourgeois revolution, which the bourgeoisie is incapable of doing, and that the proletariat must initiate the socialist revolution.

It is surely unnecessary to prove now that the bolshevist position was correct, as opposed to the menshevik position. The astonishing thing is that they who call themselves continuers of bolshevism, support the positions which the Dans, the Plekhanovs, the Tseretellis and the Kerenskys defended, when a situation similar to that of Russia of 1917, now develops in Spain.

The Russian revolution, or better said, the three Russian revolutions, the one of 1905 and the two of 1917, are for the proletarian revolution what the great French revolution, at the end of the 18th century, was for bourgeois revolutions: an exemplary standard.

In Italy, in Germany, in Austria, social-democracy insisted upon halting the revolution at the bourgeois-democratic stage. It wished to remain on the Russian basis of 1905 without arriving at the October of 1917. The defeat could not have been more overwhelming. The workers of the above mentioned countries and the international proletariat itself suffer now the consequences of the mistakes of reformist socialism, which hinders the triumph of the socialist revolution.

When the Communist International, in 1935 and 1936, considered as liquidated all perspectives of the world socialist revolution and set up the slogan of “democracy or fascism” we jumped, it seems, a hundred years backward. What is now fascism was then feudal reaction.

To the theorizers of the Communist International–many of them old mensheviks–nothing has occurred in the world in the last thirty years. They show, in the first place, a complete and total lack of comprehension of the nature of fascism. The fact that they oppose two abstract terms “democracy” and “fascism” proves their departure from Marxism.

When the bourgeoisie conquered power by an intransigent struggle against feudalism, it became dictatorial. The bourgeois dictatorship then was progressive. Cromwell and Robespierre symbolize this historic state. As the proletariat grows, it formulates demands. It wishes to have a place in the sun. It asks for bread and organizes its trade unions to make felt its requests; it wants liberty and forms its political parties to wrest it from a hostile capitalist state.

The struggle of the working class against the bourgeoisie, in an epoch in which the proletariat has not yet attained its majority, crystallizes and assumes democratic forms. The bourgeoisie, holding on to the sources of political and economic power, nevertheless is obliged to make concessions in both spheres since it can no longer ignore the working class.

The true source of democracy is not the bourgeoisie, but the working class. Only that social class which is the majority of the people can be a consistent defender of democracy to its ultimate consequences. After defeating feudalism, the bourgeoisie has always placed obstacles in the path of democratic conquests. The struggle for universal suffrage, for the right to organize, for freedom of assembly, for free speech, is the barometer which measured the great pressure of the workers’ movement. This struggle became effective thru the liberal parties of the bourgeoisie which had an eye on the conquest of political power.

But we have now entered the decadent phase of capitalism. The bourgeoisie understands that the proletariat has reached its maturity and is preparing to replace it. A democratic situation, naturally, favors the working class movement in preparing itself to engage in the final battle. In the face of this situation, the bourgeoisie, which has been reluctantly democratic when democracy was an aid to the working class, begins the speedy liquidation of every democratic vestige. It is the evolution to fascism.

Fascism is a new form of domination by the bourgeoisie which consists in handing over political power to a handful of “condottieri” and unscrupulous, regimented adventurers who exercise this power despotically by destroying all workers’ organizations and all the democratic rights gained by the working class. In this way the bourgeoisie, whose capacity for political rule has become exhausted, feels itself secure in the economic sphere and makes efforts to maintain with difficulty a social regime which is in opposition to the interests of the majority of the population, in contradiction to the necessities of society.

How is it possible, then, to pose the question of democracy or fascism? Democracy, as far as the bourgeoisie is concerned, corresponds to an outmoded period. The bourgeoisie no longer personifies democracy, but dictatorship of a fascist or semi-fascist type. Democracy today is linked up with the working class movement, with the triumph of the proletariat. To pose the problem of democracy means to bury the question of the seizure of power by the working class.

To endeavor to confine the historic question within the limits of “democracy or fascism” is an unpardonable crime, since it will not be the bourgeoisie which will bite on the hook. Such a conception will hinder the revolutionary movement of the working class precisely when the circumstances are most favorable for it, thus giving time to the counter-revolution to mobilize itself.

In a word, there would be repeated what the mensheviks desired in Russia in 1917 and what triumphed in Italy, Germany and Austria–that is, an effort to maintain the revolution within the framework of capitalism while the bourgeoisie evolves by forced marches to fascism.

The historic phase of the bourgeois revolution corresponds to the 18th and 19th centuries. In that epoch the Spanish bourgeoisie did not know how to effect its own revolution. And it did not do it because the power of feudalism, for a number of reasons which we do not have to investigate now, was so overwhelming and the strength of the bourgeoisie so relatively weak that the victory of the bourgeois revolution was not possible as in other countries. The feudal remnants grouped themselves around the monarchy. The struggle against the monarchy thus marked the first step of the liberating revolution.

The bourgeoisie made possible the restoration of the monarchy in 1874 and was not capable of overthrowing it later. This was a mission which devolved upon the working class. As the working class movement has been developing, acquiring class consciousness during the 20th century, the problem of the revolution has kept on becoming ever more clear.

The monarchy, resting upon the whole semi-feudal bourgeois system, was submerged on April 14, 1931, not merely on account of some election results but because of a wide mobilization and intense pressure of the working masses. When the monarchy fell, there was also submerged, in part, the existing capitalist regime in Spain. April 14 signified, historically, the beginning of the march to the socialist revolution.

Nevertheless, social-democracy made unspeakable efforts to aid the bourgeoisie to carry out a “decorous” bourgeois revolution. But all that resulted in failure, because it is not possible, not even with proletarian blood-infusions, to give revolutionary vigor to a social class, the bourgeoisie, which has entered the stage of decadence. The fundamental problems of the democratic revolution remained unsolved.

What is known in our recent history as the “first biennial” was no more, to put it concisely, than the overwhelming demonstration that it is impossible for the bourgeoisie to complete the bourgeois revolution, and the simultaneous proof that the Social Democrats have no solution of the problem of continuity between the democratic revolution and the socialist revolution.

On November 19, 1933, the representatives of the class forces defeated on April 14, 1931, triumphed at the polls. In two and a half years, the reactionary forces, hitherto grouped around the monarchy, had succeeded in regaining its strength, giving battle and winning it decisively. The proof could not have been more convincing. The bourgeois-democratic revolution had been a monstrous swindle. The bourgeoisie was travelling, by forced marches, toward a fascist position. It was following the road taken by other countries.

The Spanish proletariat, schooled by what had occurred in Germany and Austria, prepared to give battle to budding fascism before the latter became well organized and in a position to defeat the working class. There occurred the heroic and historic events of October 1934, culminating in the glorious insurrection of the Asturias.

The October movement was not republican in nature, that is, not a bourgeois democratic movement. It was eminently socialist in character. October signified a violent reaction against the stupid reform policy of 1931-1933 and an audacious step in the direction of socialist revolution.

It is the proletariat that fought in October, and it struggled against the reactionary bourgeoisie personified by the Republic. When the great explosion of October broke out, the petty bourgeois left republicans, struck with fear, made a gesture of revolt only to surrender later, bag and baggage, thus decapitating the movement.

October was defeated, but not conquered. The working class of the entire country became alert and far from feeling crushed, worked underground, continuing what October began.

October was the prologue to the second, the socialist revolution. The working class movement, after having written that preface with its own blood is now prepared to pass to new actions.

In the elections of February 16th, the counter-revolution was defeated. The battle of February 16 is the continuation, in a legal form, of October 1934. The struggle has as its focal point the question of October 1934. The main slogans are those of amnesty and the rehiring of the discharged workers. October triumphed, that is to say, the workers’ movement triumphed, the idea of socialist revolution triumphed!

Nevertheless, thru one of those frequent paradoxes of history, that force which externally occupies first place, that force which appears as the chief gainer, is the petty bourgeoisie, the republican movement. And it is the republicans who took power, basing themselves, to be sure, on the two working class parties–the socialist and communist.

Once more, Spanish politics seems distorted, manifesting a contradiction between what is and what ought to be. The overwhelming majority of the country is socialist. The urban workers, like the peasants, expect nothing from the pseudo-democratic republic. Their hopes go further, toward perspectives of a new social structure.

But power is enjoyed by fictitious parties which represent no more than an error. Neither Azana, nor Martinez Barrio, nor Companys have any real force behind them. The petty bourgeoisie has never had great specific gravity in Spain. And the upper bourgeoisie, does not support Azana, Companys and Martinez Barrio, but places itself openly on the side of the fascist counter-revolution. That republican parties can hold power is due to, is an index of the lack of will of the workers’ parties–socialist and communist–to set the working class on the path leading to the violent seizure of power.

There is being repeated here something analogous to what happened in Italy in 1919 and 1920. “The country was socialist,” said an observer, “but socialism did not know what to do with the country.” In effect, Spain, the entire country, desires a socialist revolution, but those who should be the most decisive leaders stubbornly adhere to the static attitude of the Popular Front. In other words, they insist that the revolution do not go beyond the limits set for it by the bourgeoisie.

The surprising and welcome development of the moment is that the masses are ahead of their leaders and their parties. The counter-offensive which took place in the entire country up to September 1934 was an intuitive movement of the masses. October was likewise an action of the masses, without any coordinating central leadership. The battle of February 16, 1936 represents another triumph of the masses. Amnesty, wrested immediately by pressure from below, is still another triumph. The general strike of April 17, declared in Madrid by mass pressure, in opposition to the leadership of the organizations, has been the last example, and not the least important.

The masses have done well, remarkably well. But a Marxist cannot believe in a constant, spontaneous capacity of the masses. The masses absolutely need a directing revolutionary party endowed with a correct Marxist policy.

Azana, as president of the government, supported by socialists and communists, proposes to stabilize the situation by consolidating the democratic republic. Is it possible that Azana and those who support him will have more persuasive force, more dominating and convincing power than German and Austrian social-democracy? Will they, perhaps, obtain in Spain what they have not been able to secure in any other place? Merely to formulate the question shows the absurdity of such a supposition.

Azana has two roads before him: either become the spearhead of bourgeois opposition to the working class movement, or be crushed between two stones: that of the bourgeoisie, on the one side, and the workers’ movement on the other. The first possibility is not unlikely, although the second is the more probable.

The offensive of the bourgeoisie had already begun. It is being carried out by all means: by unlawful acts, terrorism, demonstrations, military and fascist conspiracies, press campaigns in spite of the censorship, violent opposition in parliament, flight of capital, withdrawal of current accounts, stock exchange panic, closing of factories, conscious sabotage, disobedience of certain state laws, international press and financial campaigns, etc.

The economic situation is very grave. Within a short time, if affairs continue with the same rhythm, a financial collapse will occur similar to the ones which took place in France in 1926, in Spain in 1930 and in England in 1931. Then it is possible that the cry will be raised “truce and sacred union to save Spain,” which would be nothing but the salvation of the Spanish bourgeoisie.

Azana, in Parliament, in his first speech, said that he would carry out the program of the Popular Front, “without removing or adding a period or a comma.” This affirmation is quite significant if one takes into account the fact that the Popular Front was a compromise of an electoral character, the workers’ parties being obliged to make a series of concessions and to present only minimum demands in order to make the republican-worker coalition possible, this, they considered necessary given the state of affairs existing at the beginning of 1936. Azana does not wish to exceed the minimum demands of the workers. Will that be possible? Is it to be expected that the pressure of the masses will not break the narrow limits of Popular Front demands?

What transpired in Madrid in the middle of April is highly symptomatic and points to what may happen.

On April 14, the fifth anniversary of the proclamation of the republic was celebrated. There took place a series of unlawful acts and provocations of a fascist character. On the 16th a fascist military demonstration occurred. The situation was very serious. The working class movement understood the seriousness of the situation, contrasting the weakness of the government with the insolence of the counter-revolutionaries. The situation was favorable for a general strike to arrest the fascist advance and to oblige the government to take radical measures. But the parties and organizations which form part of the Popular Front yielded to the good promises of Mr. Azana and recommended “calm and vigilance.” But the working class movement of Madrid, with a very correct understanding of the importance of the moment, ignored its leaders, allied in the Popular Front, and went out in general strike. Fortunately, the masses go further than the Popular Front.

The Popular Front agreement says among other things that the Agrarian Reform must be carried out, that the problem of unemployment must be solved. Let us limit ourselves solely to these two aspects. Let us suppose that there really occurs that of which the Ministry of Agriculture frequently speaks. A bit of land will be given to peasants of certain Spanish provinces. But will bare land be able to satisfy these hungry peasants? They will need money to buy farm implements, seed, fertilizer, cattle. Where will they secure the necessary money? Azana said in Parliament, “We will give them money.” What cheap optimism! In order to create for the peasants economic possibilities there is no other way than to socialize the Bank. Oh! But Republicans of the Popular Front neither wish to speak nor hear of this.

Something similar occurs with the unemployment problem. “It is not a question of relief, but of providing work,” says Azana. But how to widen the possibilities for work when our economy is in chronic crisis and each day factories, mines and enterprises shut down? To take our economy out of its depression there is no other solution than to place the Bank at the service of the general welfare.

So, no matter which way we turn, we arrive at the inevitable conclusion that in order to get out of the present impassé there is no other visible perspective than to begin the realization of the socialist revolution. But since the republicans, the liberal bourgeoisie, cannot leap over their shadow, the failure of their program is as inevitable as during the first period of their rule–1931-1933.

If the Spanish proletariat had a great Marxist revolutionary party, the seizure of power by the working class would probably have been accomplished already. It has been demonstrated and it will be demonstrated again that it is impossible to confine the revolution within the limits of the bourgeois democratic revolution. History, the development of the working class, the political consciousness of the proletariat, the incapacity and contradictions of the bourgeoisie itself, the very collective needs–all lead to the final conclusion, to the socialist revolution.

The seizure of power by the working class will carry within itself the realization of the democratic revolution which the bourgeoisie cannot effect–the liberation of the land, of the nationalities, destruction of the church, economic emancipation of women, improvement of the material and spiritual position of the workers–and simultaneously will initiate the socialist revolution, socializing the land, transportation, the mines, large industry and the Bank.

Our revolution is democratic and socialist at the same time, since the triumphant proletariat has to complete a good part of the revolution which the bourgeoisie should have accomplished, and, simultaneously, has to begin the socialist revolution. The importance which the seizure of power by the workers in our country will have for the world is incalculable. It will inaugurate a period of great revolutionary uprisings, a period of destruction of fascist regimes, a period of overwhelming pressure by the enslaved people in search of their freedom.

Our country, favored by history, can, with one leap, place itself at the head of a great movement of incalculable significance. A series of circumstances make the Spanish working class today the center of hope of the world proletariat. To be sure, our workers’ movement has a number of pitfalls to avoid and subjective difficulties to conquer in order to bring its mission to a happy conclusion.

A short lived theoretical journal of the International Communist Opposition. Workers Age was the continuation of Revolutionary Age, begun in 1929 and published in New York City by the Communist Party U.S.A. Majority Group, lead by Jay Lovestone and Ben Gitlow and aligned with Bukharin in the Soviet Union and the International Communist (Right) Opposition in the Communist International. Workers Age was a weekly published between 1932 and 1941. Writers and or editors for Workers Age included Lovestone, Gitlow, Will Herberg, Lyman Fraser, Geogre F. Miles, Bertram D. Wolfe, Charles S. Zimmerman, Lewis Corey (Louis Fraina), Albert Bell, William Kruse, Jack Rubenstein, Harry Winitsky, Jack MacDonald, Bert Miller, and Ben Davidson. During the run of Workers Age, the ‘Lovestonites’ name changed from Communist Party (Majority Group) (November 1929-September 1932) to the Communist Party of the USA (Opposition) (September 1932-May 1937) to the Independent Communist Labor League (May 1937-July 1938) to the Independent Labor League of America (July 1938-January 1941), and often referred to simply as ‘CPO’ (Communist Party Opposition). While those interested in the history of Lovestone and the ‘Right Opposition’ will find the paper essential, students of the labor movement of the 1930s will find a wealth of information in its pages as well. Though small in size, the CPO plaid a leading role in a number of important unions, particularly in industry dominated by Jewish and Yiddish-speaking labor, particularly with the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union Local 22, the International Fur & Leather Workers Union, the Doll and Toy Workers Union, and the United Shoe and Leather Workers Union, as well as having influence in the New York Teachers, United Autoworkers, and others.

For a PDF of the full issue: https://archive.org/download/InternationalClassStruggleVol12Winter1936/ICS2_text.pdf