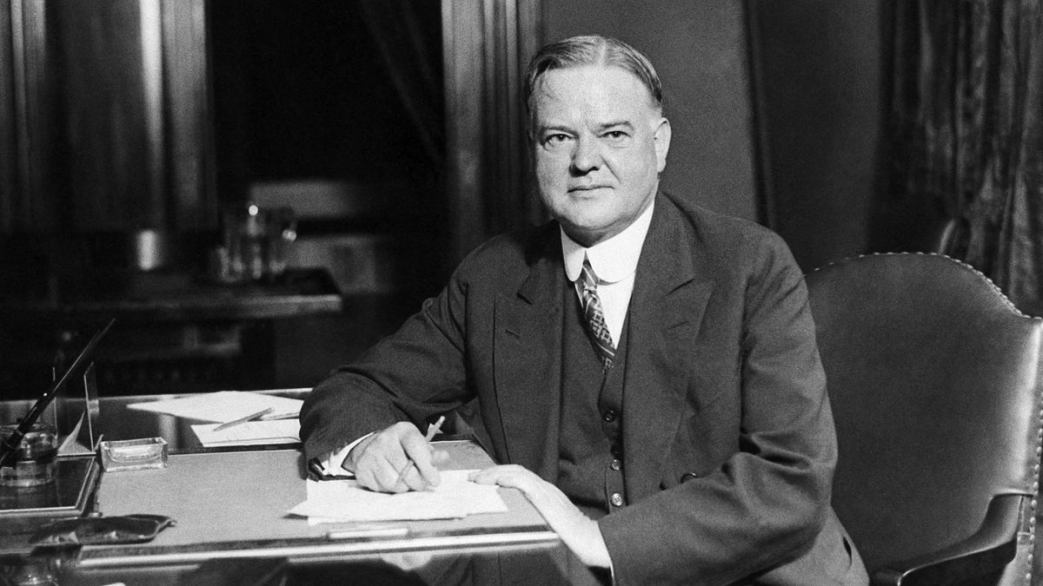

Using the crisis opened by the stock market crash of 1929, the Hoover administration passed one of the largest tariff bills, the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act, claiming it would protect U.S. industry and raise U.S. wages. Leading New York Socialist of the 1930s, and Skidmore College economics professor, Coleman B. Cheney with a popularly written explanation of the tariff’s role for the ruling class and a refutation of their claims. Spoiler: the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act did not prevent the Depression, is greatly deepened after its passage.

‘A Robber Tariff’ by Coleman B. Cheney from Labor Age. Vol. 19 No. 6. June, 1930.

REPEATEDLY have politicians declaimed that the tariff is designed and is functioning for the maintenance of high wages and good working conditions for labor; and repeatedly has labor cast large votes for high tariff Congressmen. Labor votes make possible the acts of Congress which raise the tariff rates; and labor votes could force a reversal of this policy if they chose. Is it to the interest of labor to make and keep the tariff high, or is labor being fooled by those who have a real interest in high rates and in a weaker working class?

Twenty years ago a healthy popular interest in this and other economic questions kept a constant discussion going on in regard to them. If this had continued much good might have come from it, for it is impossible for such discussion, if it does not stop too soon, to fail to bring out some truth. Today there is seldom to be heard anywhere any real argument about whether the tariff is a help or a hindrance; only a question of just how high, or, still more often, just how much higher, the rates should be. That complacence with the general principle of protection has nowhere been more in evidence than at the last convention of the American Federation of Labor at Toronto in October of 1929. The majority of the leading representatives of organized labor in the United States are either indifferent toward a high tariff or positively in favor of it. This suggests the wisdom of once more examining the effects which the tariff actually has on the wages, the security, and the bargaining power of labor.

At the outset, let it be clear that the question here concerns the protective principle only and not a revenue measure which includes a tax on imports. The tariff is often defended on the ground that even though it does cost the consumer something, the government is getting revenue and so the taxes which the consumer would otherwise have to pay are reduced. But on second thought it is evident that this notion does not correspond to the facts: protection to domestic producers is given only to the extent that foreign goods are kept out, whereas revenue is received by the government only to the extent that goods are brought in. Revenue without protection may be obtained by a tax which is not high enough to encourage domestic production; by an equal tax on domestic and imported goods; or by the prohibition of domestic production of the goods on which the duty is levied.

Among the numerous arguments that have been presented from time to time in support of the tariff, that which is commonly known as the “vested interests argument” has been increasing in importance until it now occupies not only the center of the stage, but almost the entire stage in the debates on tariff revision.

It is interesting to notice that this argument was once used chiefly against lowering the tariff, (since that would lessen profits and possibly wages in the protected industry, and thus cause loss to those who had invested their capital or their labor in that industry); but it is being used in a more positive way as a reason for actually increasing the tariff in order to protect that capital and labor invested in an industry from the increasingly severe competition from foreign producers.

Before a tariff law is passed on such grounds, several questions ought to be raised:

Protection for Profits

(1) Is there a real danger of serious losses from foreign competition, or is “protection” really demanded in order to increase profits in an already profitable industry ? When some of the Senators in Washington had the audacity recently to insist on an answer to this question, it was discovered that some of the most urgent demands for increases in rates came from the most profitable industries: e.g.—chemicals, steel, sugar, aluminum. Notice also the difference between the effect on the profits and that on the wages in such cases. While it is true that wages would undoubtedly fall or unemployment occur, or both, in case of a serious loss in any industry, it does not follow that wages and the volume of employment would necessarily increase if profits increase. Every trade unionist knows (better than many economists seem to know) that the fact a company is making profits does not mean that it is raising wages or hiring more men. The huge profits of the United States Steel Corporation have not brought high wages; the highly protected beet sugar industry pays wages that are notoriously low.

Why Special Favors?

(2) But even if there are losses, does it necessarily follow that the losers are entitled to special compensation, special protection? On what grounds are they entitled to discrimination as against other groups of citizens? Those who lose as a result of their failure to be able to meet domestic competition are not repaid. Is there any particular virtue attaching to one Pennsylvania manufacturer whose competitors happen to be in England that makes him more worthy of special governmental aid than his neighbor whose competitors are located in Indiana? As for labor, it is quite as likely to have its wages cut or its employment lessened by the competition of other Americans as by that of workers in Europe.

Other causes of unemployment are still more important than either of these: cyclical fluctuations in business and the too rapid introduction of machinery. Why is it that so few, if any, of those employers and politicians who are so concerned about the unemployment that may result from foreign competition never seem in the least concerned about the more serious unemployment from domestic causes? Then there is that vastly larger group of citizens whose only interest in the tariff is the consumers’,—the bill they have to pay. They talk much less than the manufacturers; are they on that account to be discriminated against? Yet that is what happens: those producers, whether manufacturers, farmers, or wage-earners, who are not given protection against losses from competition are obviously not being treated on a par with those given such protection. And every consumer of tariff-protected products (the exceptions are so rare they are not worth discussing) is being charged a tax, in the form of the higher prices he pays, in order that the protected industry may receive a bounty, in the form of the higher prices it receives.

This last statement calls for extra comment because there seems to be a widespread notion that the tariff costs nothing,—has no effects except to increase profits. And this notion is fostered by such statements as that of Secretary of Labor Davis, at the Toronto Convention of the American Federation of Labor, when he said, “In 1922 there was opposition to the tariff on the ground that it would increase the costs of production. The costs have decreased. It was said that the duties then proposed would raise prices. And prices have steadily fallen. It was said that the tariff would cut down imports. Our imports have vastly increased.” The three facts cited to disprove the assertions are indisputable, but they have no necessary relation to those assertions. Whether prices rise or fall depends on a multitude of factors; so the mere fact that prices were falling during a period of high tariff, tells us precisely nothing about the effect of the tariff. We must examine the tariff itself. A tariff has the sole function of discouraging imports. It does this by requiring the consumer to pay higher prices for the imported products than he would otherwise have to pay. If the foreign producers were to lower their prices so that these added duties were the same as the former prices, domestic producers would be in exactly the same position as before: they would not be “protected.” This rarely happens, however; prices are almost certain to rise and imports to be curtailed, and thus there is left a clearer field for domestic producers. It is because, and only because, the latter can sell their goods more easily and at higher prices that they want the tariff. If the tariff does not raise prices above what they would otherwise be, it is giving no protection; if it does not lessen imports below what they would otherwise be, it cannot raise prices.

Subsidy vs. Tariff

(3) If, in spite of all this, we do want to prevent loss to those who have in good faith invested their money or their skill in an industry which is unable to stand competition, is the tariff the best means of accomplishing this? It is the traditional way, but certainly not the only way. A subsidy to the weak industry would accomplish precisely the same results; and labor could be protected from serious loss during a transitional period by unemployment insurance. Both these means are worth examining.

The most important differences between a subsidy and a tariff are our more definite knowledge of the cost of the former; our constant awareness of that cost; and the distribution of that cost. The first two of these facts probably account for the greater popularity of the tariff; we have been taxed without being fully aware of it, sometimes without knowing anything about it, except perhaps as we realized that the cost of living was very high. And politicians have adopted it because of that popular indifference. It would seem, however, that between two policies, the cost of one of which is easily and definitely measurable while that of the other is very difficult 10 measure at all, the former would be the more desirable, unless the cost were considerably higher. As a matter of fact, the cost of subsidy would be at least no higher, and probably lower, than that of a tariff. This rise in price measures the amount of the protection given to domestic producers. Since we do not know exactly how much higher the price is than it would be without the tariff, we do not know just how much protection we are giving. Consequently we sometimes give more than is necessary to accomplish the result aimed at, or continue it unnecessarily long, and so pay more than we would be likely to pay in the form of a subsidy. Furthermore, the cost of collecting customs duties and of preventing imports from coming in without paying is tremendous; undoubtedly more than the administrative cost of paying a subsidy.

Burdening the Consumer

The other difference between a subsidy and a tariff is equally important: the incidence of the cost. If, for example, it should be decided that the growing of beets for sugar is an industry without which American civilization would be a failure., and that there would be no such industry without the aid of the government, the cost of such aid might be imposed on the consumers, in proportion to the amounts consumed, or it might be divided among all citizens in the same ways that the general expenses of government are apportioned. If the industry is to be supported for the general good, it seems rather obvious that it is fairer for the burden to be borne by the nation as a whole rather than by the consumers of a single product. The fact that this product, sugar, is consumed by practically every person in the country makes the case in no way less clearly in favor of the subsidy. A family with an income of $1,200 a year consumes almost as much sugar as one with $12,000. A tariff would thus impose almost as great a tax, in absolute amount, on the one as on the other, and the rate of taxation would be higher on the smaller income than on the larger. This is, of course, directly contrary to the general theory recognized in our income and inheritance taxes, that higher rates should be paid by the larger incomes.

When unemployment results from competition which cannot be met, provision ought to be made to prevent the suffering and want that so often result. But this provision ought to be made whether this unemployment is the result of domestic or foreign competition, and this the tariff does not and cannot do. It applies only in the case of foreign competition. Unemployment insurance, on the contrary, is a remedy (for it is a remedy as well as a relief) which works equally well whichever (or whatever) be the cause. It cannot be discussed here in any detail; but there has been enough experience with it in European counties to prove that it is fundamentally sound in principle and successful in operation.

High Tariff Does Not Raise Wages

The old argument that the general level of wages is raised by the tariff has been so often refuted that it is almost superfluous to mention it; yet it does persist. But most certainly a tariff cannot increase the skill of labor, the amount of capital, the amount and quality of the natural resources, the efficiency of management, or the bargaining power of labor relative to that of capital ; and these are the factors which determine the general wage level. What it does do is to shift labor and capital from some industries to others. It does this by raising the prices of certain products, thus making it possible for those industries to compete with other domestic industries in bidding for labor and capital. That is, it raises the amount which those industries are able to pay as wages, up to the level that other industries are already paying; and similarly as to interest. At the same time it injures other industries by lessening their foreign markets: if we buy less from abroad (less than we otherwise would buy,—not necessarily less than we bought last year, and this the tariff makes us do if it is successful) then we can sell less abroad. We could give goods away, of course; and for a short time gold could be sent, and after that paper promises, but we can live on neither of these. Cutting down imports inevitably cuts down exports. (The automobile manufacturers are beginning to realize this and therefore to question the sacredness of the tariff.)

We cannot tell in advance and perhaps not afterwards, which of the many exporting industries are so affected, but it is absolutely certain that some of them are. (The fact that agricultural commodities have throughout our history constituted our most important exports and the fact that farmers lack the homogeneity and certain other qualities which seem to be possessed by manufacturers, account in large part for the ease with which manufacturers have obtained and maintained the high tariff.) This shifting of labor and capital might possibly result in a greater demand for labor and thus for the time being at least have a tendency to raise the general level of wages. This would be true if the industries encouraged demanded more labor in proportion to the fixed capital than did the industries which were discouraged. The most casual observation of the actual process of tariff making, however, will quickly convince one that that object has never yet been the goal of American tariff policy. The public has recently learned enough about how tariff schedules are actually made from the Lobby Investigation Committee’s exposure of the work of Messrs. Eyanson, Grundy, Arnold, and others, to make it unnecessary to go into any details. Certainly the present Senator Grundy is not fighting for a tariff to strengthen the position of labor.

A single illustration of tariff rate-fixing in practice may be interesting, however. Under the rule which allows the President to raise or lower tariffs on the recommendation of the Tariff Commission, President Coolidge on October 17, 1928, advanced the rate by the maximum amount allowed, on fluorspar, a mineral used in the manufacture of steel. The interesting feature is that the product is controlled in the United States almost entirely by two companies, one of which is owned by the Mellon interests, the other by the McLeans of Washington. In neither case does it appear that the domestic producer was in danger of great losses, or that if such had been the case, it would have resulted in injury to the public. If this tariff increase is at all effective, it will mean increased profits to the McLeans and the Mellons, but certainly it cannot be regarded as a boon to labor, either in its intent or its result. And it is fairly typical of tariff schedules in general.

How Old Is An Infant?

The claim that the tariff would be. used to promote new industries through the period of their “infancy” is less often heard in these times. When it is heard, however, the same sort of questions and some others besides should be applied to that claim as to the one we have just been discussing; such other questions as whether politicians are generally considered to be more accurate and more far-sighted in forecasting the future of industry than are the capitalists; and how long the “infancy” of an industry is to last. The demand for the diversification of industry for cultural reasons is, of course, out of date for such a country as the United States; and the same demand for military purposes, while never very important in as large and as resourceful a nation as this, can certainly not be given much weight since the acceptance of the Kellogg Peace Pact. But if there is thought to exist a need for artificial aid on these grounds, what has been said about the subsidy applies here with particular emphasis.

With the recognition that the doctrine of laissez-faire is going out of fashion, there seems to be some confusion of the principle of protection of labor by labor legislation with that of protection of corporations by tariff walls. The two notions look much alike, but they are essentially different. The former is based on the facts that the welfare of society depends on the health and well-being of its members, most of whom are workers, and that the worker is unequal in bargaining power to the corporation. Tariff protection, on the other hand, is a shielding of one group of corporations from another group, not because the latter is more powerful and likely to be unscrupulous in the use of its power, but merely because it happens to be in foreign countries. This is obviously a very different sort of thing.

Then the claim is made that labor too may be protected against the foreign producer and the low wage rate of most foreign countries; and that protection of this sort is the same as protection against those in this country who, without legislation, would be willing, or required, to work under dangerous and unhealthful conditions. There is some point to this, but three major qualifications will reduce it to small proportions. In the first place, the greater part of the differences between the wage rates of this country and those abroad is due, not to the low standard of living, but to the lower productivity of labor. Labor cost per unit of product is very often higher abroad. (It is true that the standard of living may in turn have some effect on the productivity, but the principal cause of low productivity in Europe is the scarcity of natural resources as compared to those in this country. In the Far East it is lack of capital and organization. The standard of living is, in the main, the result, rather than the cause.) In the second place, a tariff wall around the United States, by making it harder for the producers in other countries to sell their goods here, would tend to depress the standards of wages and conditions in those countries still further, and thus help to make the status of labor abroad worse rather than better. In turn this would make the competition more severe,—and a vicious circle would be set up from which the tariff could never offer any means of escape. Finally, the notion of protecting American wage-earners by legislation against the competition of foreign labor is somewhat ludicrous the light of the fact that the United States has the least satisfactory labor legislation of all the important industrial nations of the world.

In summary then, the tariff for protection affects labor by raising the prices of protected products and thus the cost of living; by making it possible thereby for certain industries, at the expense of others which have the natural advantages, to pay wages as high as other domestic industries are already paying; and by strengthening the bargaining power of employers through increased profits. It conceivably could be, though it rarely if ever has been, used for the benefit of labor. But if such benefit is needed, it can be obtained by other means which would give the benefit more directly and therefore more surely to those it is intended to benefit and which would impose a known cost on those who ought to bear it.

Labor Age was a left-labor monthly magazine with origins in Socialist Review, journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Published by the Labor Publication Society from 1921-1933 aligned with the League for Industrial Democracy of left-wing trade unionists across industries. During 1929-33 the magazine was affiliated with the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) led by A. J. Muste. James Maurer, Harry W. Laidler, and Louis Budenz were also writers. The orientation of the magazine was industrial unionism, planning, nationalization, and was illustrated with photos and cartoons. With its stress on worker education, social unionism and rank and file activism, it is one of the essential journals of the radical US labor socialist movement of its time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborage/v19n06-Jun-1930-Labor-Age.pdf