Meyer Schapiro, a leading Marxist art historian and critic of the 20th century, with a critique of Frank Lloyd Wright’s world-view and how the architect’s Broadacre City project reflected it.

‘Frank Lloyd Wright: Architect’s Utopia’ by Meyer Schapiro from Partisan Review. Vol. 4 No. 4. March, 1938.

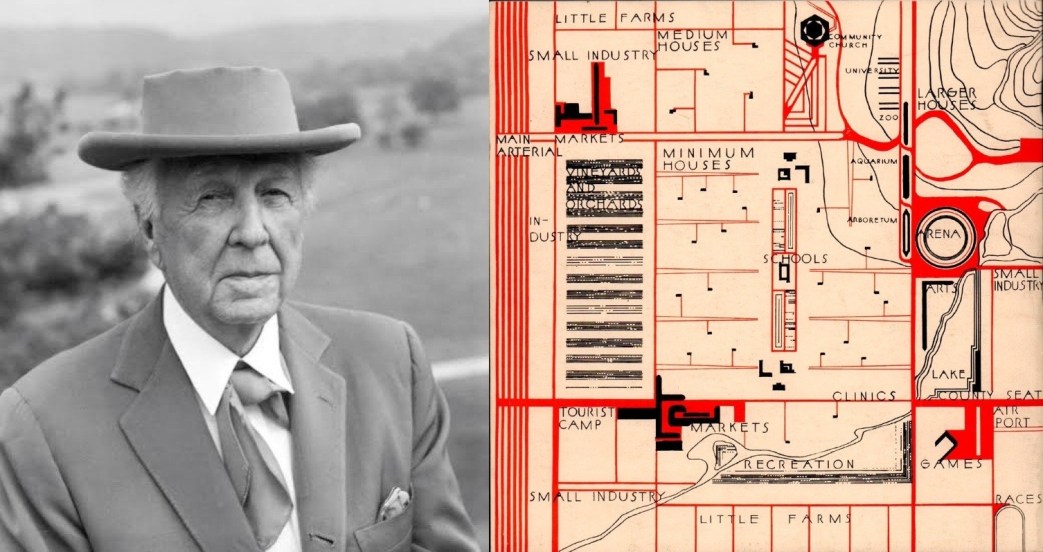

Frank Lloyd Wright believes that only “organic architecture” or primitive Christianity—”Jesus, the gentle anarchist”—can solve the crisis. This was also the theme of his earlier book, The Disappearing City, written in the depths of the depression. If we forget the undergraduate poetizing of the great architect, now seventy years old (“the earth is prostrate, prostitute to the sun”), and his no less profound philosophizing (“what, then, is life?”), and if we strip his argument of the grand, neo-Biblical and neo-Whitmanesque theogonic jargon of “integral,” “organic” and the man “individual,” we come at last to a familiar doctrine of innocence and original sin and a pian of redemption by rural housing. According to Wright (and this is developed in detail by Brownell) a primitive state of democratic individualism in the Eden of the small towns and the farms was perverted by the cities. A privileged class arose which did not know how to administer its wealth in the common interest; and what remained of the native culture was corrupted by the immigrants. But by an internal law that regulates the fortunes of mankind, swinging life back to its healthy starting-point when it has gone too far toward decay, salvation comes through the evil itself. As the city grows, it is choked by its own traffic and reawakens the nomadic instincts of man. Its own requirements of efficiency gradually bring about decentralization. And the insecurity of life in the city forces people back to the soil where their living depends on themselves alone and a healthy individualism can thrive. In the Broadacre City, already designed by Wright in his earlier book, the urban refugee will have his acre of ground on which to grow some vegetables; he will work several days a week in a factory some miles away, accessible in his second-hand Ford; the cash income will supplement the garden; and through these combined labors he will enjoy a balanced life in nature. The new integrity of the individual will bring about the end of speculation and commercial standards.

The deurbanizing of life, the fusion of city and country on a high productive level, is an ideal shared by socialists and anarchists. But when presented as in Wright’s books as an immediate solution of the crisis, it takes on another sense. It is the plan of Ford and Swope, a scheme of permanent subsistence farming with a corvée of worksharing in the distant mill, of scattered national company villages under a reduced living standard. The homes of Broadacre City may be of the most recent and efficient materials; they may be designed by the ablest architects—“integrated” and “organic” as Wright assures us they will be; but all these are perfectly consistent with physical and spiritual decay. Social well-being is not simply an architectural problem. A prison may be a work of art and a triumph of ingenuity. The economic conditions that determine freedom and a decent living are largely ignored by Wright. He foresees, in fact, the poverty of these new feudal settlements when he provides that the worker set up his own factory-made house, part by part, according to his means, beginning with a toilet and kitchen, and adding other rooms as he earns the means by his labor in the factory. His indifference to property relations and the state, his admission of private industry and second-hand Fords in this idyllic world of amphibian labor, betray its reactionary character. Already under the dictatorship of Napoleon III, the state farms, partly inspired by the old Utopias, were the official solution of unemployment. The democratic Wright may attack rent and profit and interest, but apart from some passing reference to the single-tax he avoids the question of class and power.

The outlines of Wright’s new society are left unclear; they are like the content of his godless religion for which he specifies a church in Broadacre City. After all, he is an architect telling you what a fine home he can build you in the country; it is not his business to discuss economics and class relations. But in the chapters by his collaborator, Brownell, who has more to say about technology, economics and culture (although the consequences are not faced in any field), the reactionary side of this shabby, streamlined Utopia becomes more evident.

The core of his argument is the critique of bourgeois society made over a hundred years ago by both the right and the left and repeated since, that it destroys idyllic values, dehumanizes man, disperses his interests and activity and subjects him to the machine. But following the right, he opposes to it the ideal of a self-sufficient agrarian culture on the Borsodi plan, with its elaborate household industry. By converting the middle class—the real subject of his anxiety—into a conservative peasantry, he hopes to restore their “human integrity.” There is little direct reference to exploitation and war and the everyday brutalities of class power; where he has to deal with the clash of interests, his thought becomes blurred or allegorical. The historical movements of our time are transposed into conflicts between shadowy principles. The great and primary struggle is between “relativism” and “absolutism”: an inherent tendency toward freedom and creativeness (relativity) meets an opposite inherent tendency toward “absolutism.” Beside this “primarily intellectual conflict” there are three lesser ones: Urbanism vs. Agrarianism, Security vs. Opportunity, Specialization vs. Integrity, the latter two being individual, not social, problems. Ignorant of socialist theory, of which he has acquired some elements of the vocabulary, he caricatures socialist ideas in a half-baked manner. He is against socialism because it is necessarily centralized and urban, surrendering freedom for security, but also because it is “essentially insecure, unstable, destructive of human values of life.” He can speak in the same work of the economic causes of crises, but also of the decay of western Europe and the economic disasters of the United States as “natural functions of the overgrown urbanism and cosmopolitanism of these times.” He cannot explain why security should decline as productive power increases; “the disorganization of personal life” is not the cause, as he thinks, but only an effect.

His own agrarian solution involves a similar indifference to economic facts. The interdependence of agriculture and industry, of production and the market, is nowhere analyzed and the obvious practical objections remain unanswered. He does not ask: what will be the effect of such a return to the soil and the self-sufficiency he advocates on the millions of farmers (with their tenants and laborers) who depend on cash crops and already find their market dwindling? or the effect of the lower income of the semi-industrial workers on the same agricultural market? He recommends a revival of household industry with modern machines as an essential part of the new agrarianism. But how can the farmer who grows crops only for himself afford this elaborate plant for producing his own household goods?

Characteristically enough, Brownell approves the trend toward industrial decentralization, not seeing that it coincides with an even greater concentration of ownership and a greater poverty of the masses. He innocently looks forward to a broader distribution of productive property as one of the results of this trend; but in the name of a mysterious concept of balance he would preserve centralized private control of some industries and a decentralized private ownership of others. Although the self-sufficiency of the farms in his ideal America is to rest upon the use of machines, he deplores the drift of the farm youth to the cities, which is due precisely to the mechanizing of agriculture.

His whole approach is based on the pathetic polarities of stability and movement, order and restlessness, the land and the city, formulated by the folk-loving, but anti-democratic, romantic reaction at the beginning of the nineteenth century. He has inherited its stock antitheses of security and insecurity, the whole and the fragment, the organic and the inorganic; and added like his predecessors other categories appropriate to the politics and science of the moment. There are indeed personal nuances, but in the muddled form of the whole, with its eclectic hyphenation of doctrines, they are as insignificant as the lyrical delicacies of the more learned Nazis. Like the religious and feudal reactionaries of the last century and their fascist successors, Brownell wants a “balanced” and an “integral” society. But balance, he admits, is not good in all fields. In population, for example, a homogeneous racial and national stock is preferable to a “balance of stocks.” Nevertheless, he finds “an integrated life” only in the South. And as he goes on to specify the ideals of his “natural” agrarian culture, he begins to resemble the fascists to a hair. He attacks the declining birth-rate and the increasing longevity. The old are uncreative and useless; big families, especially big rural families, with plenty of young men, are needed to effect the balance and the integration.

And these big families must produce in their domestic factories an American “folk art and a folk religion and even a folk education” to end the cultural crisis. Brownell shares the Nazi enthusiasm and vagueness about the folk as a classless primordial “natural” mass which he opposes to the landless immigrants with their “unnatural” and un-American urban interests. “Surely one of the main influences toward a more integrated life and culture is the nature of the American people. They are not suited to urban lives and extreme specialization. The agrarian tradition is deeply in them.” But strangely enough jazz music in its dynamic character becomes for him an American folk product, although in his yearning for repose he has criticized this dynamism as a foreign and urban perversion.

The contradictions and naivetés of this book are so numerous that the informed reader can have little confidence in the authors. He is struck again and again by the contrast between their reverence for technique and science and their complete failure to analyze the social mechanism they have in mind and the means for realizing their goals. They are obsessed by modern life as an expression of something peculiar to the moment, but are wholly unable to make an historical explanation. The idea that society is known through its reflections permits a crude analogical thinking and the flattest impressionist substitutes for a rounded historical study. The pages devoted by Wright to architectural style are no better; he says little that is precise about the forms of contemporary building, and his survey of past architecture is a grotesque parody of the views of the 1880s, a home-made affair based on old readings and the artistic propaganda of the pioneers of the modern movement. All architecture after the fourteenth century is regarded as decadent, and post-mediaeval painting as merely photographic.

The social imagination of Wright should not be classed with that of the great Utopians whom he seems to resemble. Their energy, their passion for justice and their constructive fantasy were of another and higher order and embodied the most advanced insights of their time. The thought of Wright, on the other hand, is improvised, vagrant and personal at a moment when the social values and relations he expounds have already long been the subject of critical analysis and scientific formulation. He is not in the direct line of the Utopians, but his social criticism as an architect is in many ways characteristic of modern architectual prophecy and has its European parallels, though addressed to an American middle class. During the last fifty years the literature of building has acquired a distinctive reformist and prophetic tone. The architects demand a new style to fit a new civilization, or if the civilization has become problematic, they propose a new architecture to reform it. In either case, the architect, unlike the poet or the painter, is a practical critic of affairs. Even his aesthetic programs are permeated with the language of efficiency, and underneath his ideals of simplicity and a flexible order we can detect the emulation of the engineer. As a technician who must design for a widening market, he can foresee endless material possibilities of his art, and by the existing standards he can judge the wretchedness of the average home. The whole land cries out to be rebuilt, while he himself, inventive and energetic, remains unemployed. But his social insight is limited by his professional sphere; in general, the architect knows the people whom he serves mainly in terms of their resources and their tastes. Their economic role, their active relation to other classes, escape him. His certainty that architecture is a mirror of society does not permit him to grasp the social structure. The correspondences of architecture and “life” by which he hopes to confirm the historic necessity of his new style, these are largely on the surface, reflections of reflections: architecture, for Wright, is “a spirit of the spirit of man.” Hence Le Corbusier could wonder how such pillars of efficiency and honor as the bankers tolerated the sham facades of their banks; he offered to protect them from revolution by designing hygienically superior workers’ homes. Today, Wright returning from Russia finds it hard “to be reconciled to the delays Russia is experiencing no matter how cheerfully in getting the architecture characteristic of her new life and freedom.” But he explains the “falsity” of the current bureaucratic classicism of the public buildings by Stalin’s eagerness to please the people who want the luxuries once enjoyed by their masters. “If Stalin is betraying the revolution, then I say he is betraying it into the hands of the Russian people” (Architectural Record, Oct. 1937).

This blindness to the facts of social and economic power makes possible the visionary confidence with which architects like Wright correct society on the drawing-board. Accustomed to designing plans, which others will carry out and for which the means of realization already exist, they assume for themselves the same role or division of labor in the work of social change. The conditions which inspired their architectural inventiveness are more like those which preside over reforms than over revolution. Through their designs they have effected the almost daily transformation of the cities, and when society has to be rebuilt, their self-assurance as prophetic forces is strengthened by the current demands for housing and public works as the only measures against ruin. Their reformist sentiments are echoed by the architectural metaphors of planning, construction, foundations, bases and frameworks in the language of economic and social reform. Advanced architects who have only contempt for the grandiose, unrealistic projects of academic architectural competitions, relapse into social planning of the same vastness and practical insignificance. They are subject especially to the illusion that because they are designing for a larger and larger mass of people they are directly furthering democracy through their work; Mumford, for example, supposed that the use of the same kind of electric bulb by the rich and the poor was a sign of the inherent democratic effects of modern technology. The existence of fascism is the brutal answer to such fantasies.

To the degree that the crisis is judged psychologically as the result of “restlessness” and is neurotically laid to a “faulty environment” or to mistakes of the past, the architectural utopia of Wright, the specialist in new environments, must seem really convincing to those from whom the economic reality is hidden. Around the private middle-class dwelling cluster such strong and deep memories of security that the restoration of the home appears in itself a radical social cure. Throughout his books Wright insists that architecture is the art which gives man a sense of stability in an unstable world, and that of all styles of building the modern is the most “organic.” “The old is chaos, restlessness”; the new, “integral, organic, is order, repose,” he writes,—-like the modern mystics of the state and church. In his survey of modern architecture—otherwise so meagre—Wright tells in detail how he built the Imperial Hotel of Tokyo on marshy ground, and how this building alone withstood the earthquake of 1923. But social earthquakes are not circumvented by cantilevers and light partitions.

In spite of the exaggerations and errors of Wright in giving architecture an independent role in shaping social life, the experience of his profession has a vital bearing on socialism. But it is just this bearing that Wright and Brownell, as spokesmen for the middle class, ignore. They have failed to recognize—what must be apparent on a little reflection—that the progress of architecture to-day depends not only on large-scale planning and production, but also on the continuity of this production and on a rising living standard of the whole mass of the people–conditions irreconcilable with private control of industry. It is only when all three conditions are present that the architect can experiment freely and control the multiplicity of factors which now enter invariably into his art. Monopoly capitalism and its political regimes also plan on a large scale, within certain limits, but they are fatally tied to crises and war and declining standards of life (not to mention political and cultural repression) which limit the architect at every point. The masses cannot afford good homes and the intervention of the capitalist state in housing is tentative and even reactionary, since it helps to perpetuate lower standards and supports the familiar speculative swindles. Moreover, even under more prosperous conditions, the great mass of architects have no chance for original artistic creation; they are salaried workers submerged in a capitalist office, with little possibility of self-development. The architect cannot be indifferent to these as merely economic and material factors inferior to creative problems. The latter are not posed unless the architect can really build, and the quality of the solutions depends in part on the freedom of the architect in realizing his designs. In our day the best architects have built very little during the last eight years, at a time when the need of new construction was universally admitted. Even the slight upswing just experienced has already subsided and architects face a desperate future. A return to the soil, far from stimulating architecture, can only depress it further.

ARCHITECTURE AND MODERN LIFE. By Baker Brownell and Frank Lloyd Wright. Harper & Bros. $4.00.

Partisan Review began in New York City in 1934 as a ‘Bi-Monthly of Revolutionary Literature’ by the CP-sponsored John Reed Club of New York. Published and edited by Philip Rahv and William Phillips, in some ways PR was seen as an auxiliary and refutation of The New Masses. Focused on fiction and Marxist artistic and literary discussion, at the beginning Partisan Review attracted writers outside of the Communist Party, and its seeming independence brought into conflict with Party stalwarts like Mike Gold and Granville Hicks. In 1936 as part of its Popular Front, the Communist Party wound down the John Reed Clubs and launched the League of American Writers. The editors of PR editors Phillips and Rahv were unconvinced by the change, and the Party suspended publication from October 1936 until it was relaunched in December 1937. Soon, a new cast of editors and writers, including Dwight Macdonald and F. W. Dupee, James Burnham and Sidney Hook brought PR out of the Communist Party orbit entirely, while still maintaining a radical orientation, leading the CP to complain bitterly that their paper had been ‘stolen’ by ‘Trotskyites.’ By the end of the 1930s, with the Nazi-Soviet Pact of 1939, the magazine, including old editors Rahv and Phillips, increasingly moved to an anti-Communist position. Anti-Communism becoming its main preoccupation after the war as it continued to move to the right until it became an asset of the CIA’s in the 1950s.

Access to full issue: https://archive.org/download/sim_partisan-review_1938-03_4_4/sim_partisan-review_1938-03_4_4.pdf