Under the impact of a rising Black freedom movement, the Russian and colonial revolutions, and the insistence of the new Communist International, the overwhelmingly white revolutionary workers’ movement in the U.S. was forced to reassess its past and reorient itself to the growing Black proletariat and its demands. An important series of articles in that shift were these by William F. Dunne, among the most authoritative labor and union voices in the Communist Party, of which he was a top leader, beginning with a personal understanding of his own history from a child called “poor white trash” to organizing the racial cauldron of the Chicago stockyards.

‘Negroes In American Industry’ by William F. Dunne from Workers Monthly. Vol. 4 Nos. 5 & 6. March & April, 1925.

As I look back over the years I can see that we were probably “poor white trash.”

We lived on Minnesota Avenue, and Joey, a little Negro boy whose last name I do not remember ever hearing, was my first playmate while we lived in Kansas City. Certainly we were miserably poor; that we belonged to the white race has never been disputed and justification for the supposition that we were “trash” is furnished by the distinct memory of being called “n***r lover,” by older children when Joey and I ventured onto the nearby vacant lot whose garbage piles furnished an inexhaustible store of treasure for the younger set of the neighborhood.

I remember that the epithet held no approbrious meaning for me, but nevertheless I resented it just as an Irishman, an Englishman or a Swede resents being classified nationally in a certain tone of voice. My attempts to revenge what was evidently, for reasons not understood by me, intended for an insult were not singularly successful. Joey was too goodnatured to be of much value as an ally and the conflicts were generally in the nature of rear guard actions ending in the retreat of the three of us, Joey, myself and Rover, one of the nondescript dogs with which Kansas City abounded and which Joey and I had adopted, to the fastnesses of the kitchen of one of our mothers—our houses were side by side—or to the woodshed.

Our mothers were singularly uniformed as to the reasons for our troubles and unbelievably unsympathetic—particularly towards Rover. Our fathers we saw but seldom. They worked in the Armour packinghouse and were on their way to work before Joey and I arose in the mornings. They went to bed at an early hour and so did we.

We were governed by a matriarchy.

Overshadowing all else as a source of danger to Joey, Rover and me was the city dog-catcher. He was the terror of the neighborhood children who were all well supplied with unlicensed prototypes of Rover, and whatever differences existed between the races were submerged in the face of this common enemy. His advent into the district was made known by a sort of grapvine telegraph that was surprisingly efficient. Even the dogs sensed the danger and as a rule they made no protest when hurried into woodsheds and cellars.

Rover was an exception. I do not know if his mongrel heart held a sort of fearless defiance or if he was simply in rebellion against an exercise of authority but the fact remains that Rover would howl to high heaven at the most critical moments when the enemy was within earshot.

On one terrible day the grapevine failed to work and the enemy was within the gates. Joey and I adopted desperate measures. I stole a pair of mother’s stockings and we lashed Royer’s legs fore and aft. Joey stripped his three year old sister of her sole garment—a frock fashioned on severely simple lines—and with this emergency muffler we bound Rover’s jaws while she ran screaming her protest in chocolate-colored nakedness.

Our mothers arrived as we were contemplating our work with justifiable pride. They lost no time debating the course to pursue. My mother seized Joey, Joey’s mother grabbed me. With a loud smacking noise, black hand descended on white bottom and vice versa.

Joey and I left home that day with two slices of bread and three cold fried catfish to brave a world that we felt could be no more hostile than homes ruled by mothers to whom an undressed female child was of more importance than the liberty of Rover.

We were captured within four blocks of our domiciles, spanked again on already tender areas and put to bed after our commissariat had been raided.

You ask what the foregoing has to do with the Negro in industry and I reply that the Negro in industry encounters a hostility from white workers that is artificial and not instinctive, that my childhood experience is that of thousands of white children who feel no hostility toward their Negro playmates until old enough to absorb the prejudices of their elders.

Nothing is clearer than this in the report of the Chicago commission on race relations–the most exhaustive and authoritative study of the real problem yet made in the United States and which was begun after the 1919 race riots.

The problem of the Negro in industry as well as in American society as a whole, is a problem created by the background of chattel slavery and intimately connected with its traditions, the propagation of a whole series of falsehoods and fetishes, scientifically untenable, but which by repetition and a certain superficial plausibility, have become dogmas which to question means social ostracism in the former slave states—the historical home of chattel slavery whose conceptions of the Negro as a social inferior who menaces white supremacy is the obscene fountain from which flows all of the poisonous streams that carry the virus of race hatred into he ranks of the American working class and the labor movement. Slavery not Abolished.

The slave south is not dead and slavery has not been abolished. It lives in song and story, it lives in every community where there are black and white human beings, it lives in the agricultural regions of the south, it exists in the industrial feudalism of the lumber and turpentine camps of the south, it lives in the southern non-union coal fields, it lives in the columns of the capitalist press of both north and south and the prejudice and strife among the workers is fed and inflamed like a gangrenous wound by this filth that it exudes.

The problem of the Negro in industry—it is really the problem of the dominant white workers if a white working class exploited as the American working class is can be termed dominant—must be approached from two viewpoints that of the Negro and that of the white worker. Both have their prejudices. Both are victims of constant and cunning misinformation supplied them with a deliberate aim and- a diabolical cleverness hard to combat. But it must never be forgotten by those who see the danger to the workers of both races and consequently to the whole working class movement, that while the prejudices of the white workers have absolutely no foundation in fact, those of the Negro workers are, although a grave danger to working class solidarity and serious obstacles to organizing work, based upon enslavement, persecution and torture of black by white since 1619.

The Negro worker is the injured party and because he is, because the dominant white knows he is, the changes are rung on the unprovable assumptions concerning the mental and moral inferiority of the Negro as an individual and as a race in an attempt to justify the denial of political rights, denial of equal educational privileges, Jim Crowism, discrimination in unions, mass murder in race riots, hangings, burnings at the stake and the rest of the long list of Dantesque horrors inflicted on the black race since its first representative was torn from his African home by white slave merchants.

Borrowed Prejudices.

The opinions of the working class in all social epochs up to the immediate period preceding revolution, according to the easily demonstrable Marxian theory, are the opinions of the ruling class. This applies with the greatest force to the opinions held by whites of the Negro. The white ruling class of the south has conspired since the civil war to deprive the Negro of every economic and political right. The rise of a Negro middle class has been fought consistently and white workers, imbued with the prejudices of their rulers have been only too glad to have inferiors to whom they could transmit the kicks given their own posteriors by the feudal aristocracy and the rising industrial capitalists of Dixieland.

The final argument for the suppression of the Negro with which disagreement must be accompanied by readiness to defend one’s life against both white southern workers and capitalists and the social strata lying between, takes the form of the inevitable question: “Would you want your sister to marry a black blankety blankety blank blank blank?”

This is the form into which the hatred and fear of granting equal opportunity to the Negro rationalises itself. It is the sexual motif which lies like a thick and fetid blanket over the whole south, extending into the north as well, but as a thinner fabric in which rents are appearing, rents torn by the inexorable forces of industrial, political and social development in the United States.

Into the labor movement itself has been catapulted the monstrous fallacy, promulgated by a decadent feudalism based on complete subjection of the Negroes, that the black race individually and collectively, lusts with an ungovernable passion for the bodies of white women. This false dogma has been and is used to excuse all overt acts against the Negro on the part of whites when all other excuses fail. The white press and pulpit, the lecture platform, the moving pictures, silly but white ego-satisfying books of the Nordicmaniacs, are used to perpetuate this easy and effective means of alienating all sympathy for the Negro even when he has been made the victim of the sadistic appetites of whole communities of maddened degenerates as in Mississippi, Jan. 26, 1919, where the burning of a Negro at the stake was advertised in the press for several days, the announcement of the hour at which the officers of the law would turn him over to the mob was made and special trains were run to accommodate the curious—a desperate spectacle without parallel unless we except the holocausts of Christians in ancient Rome.

A volume could be written or this phase of the race question alone but it is enough to say here that in other countries where there are large Negro populations, the sexual question does not arise. In the British West Indies, where the Negroes outnumber the whites 50 or 60 to one, according to the statement of Lord Olivier, formerly governor-general of Jamaica, no case is on record of an attack on a white woman by a Negro.

This instance alone is enough to discredit the whole myth of rape of white women as the basis of hostility to the Negro even if there were not available the testimony of competent and unprejudiced investigators who, without significant exception, are agreed that the opposite is true—a pronounced penchant of white southerners for Negro women the millions of mulattoes are alone proof of the soundness of this conclusion—and that it is extremely doubtful if a dozen cases of attack on white women could be proved as fact in the whole horrid history of the innumerable lynchings of Negroes.

So much for the justification on moral grounds of discrimination against the Negro in the labor unions and industry as a whole.

Is the Negro a “Natural” Strikebreaker?

But the discrimination of the unions against the Negro worker is justified by the white workers on other than moral grounds in the north. He is accused of being an incurable strikebreaker and therefore a willing tool of the employers.

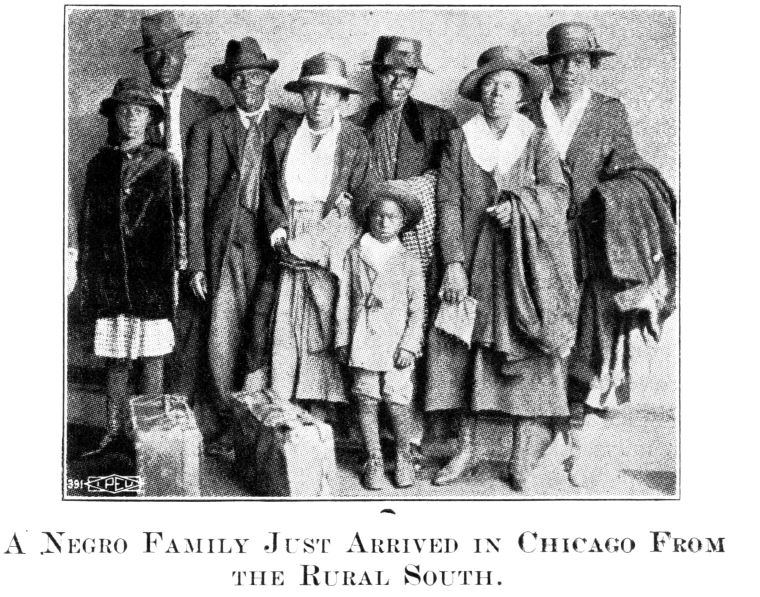

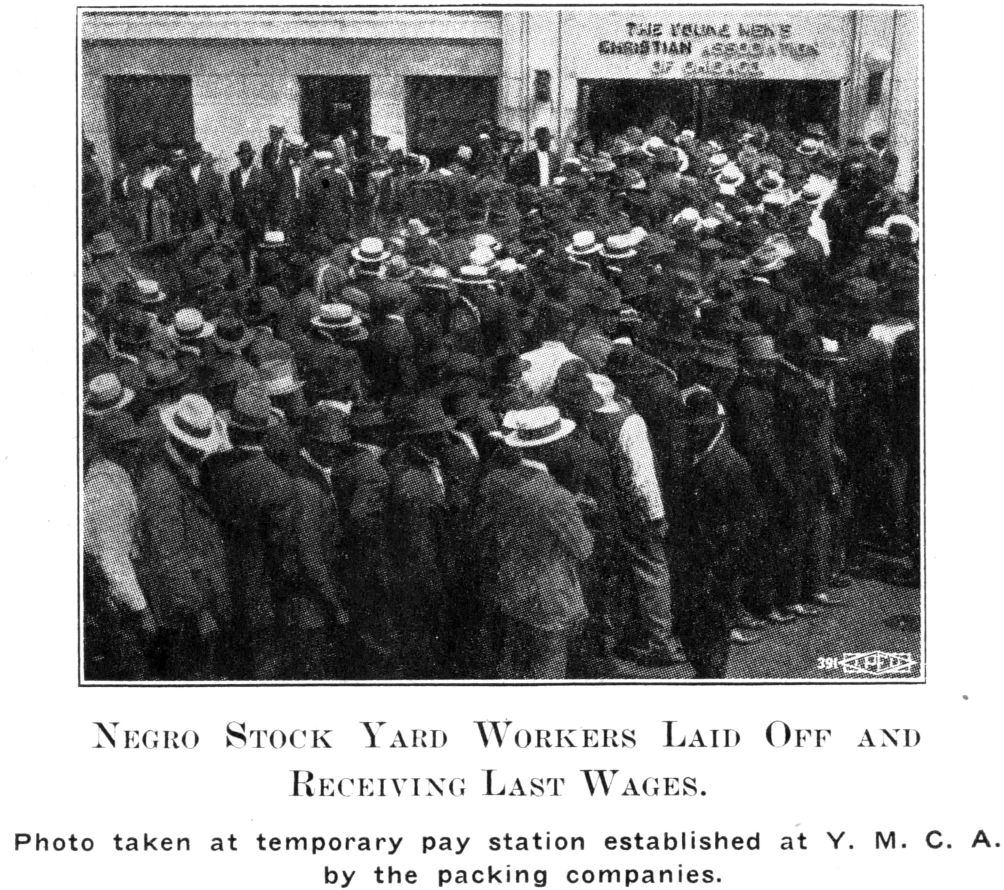

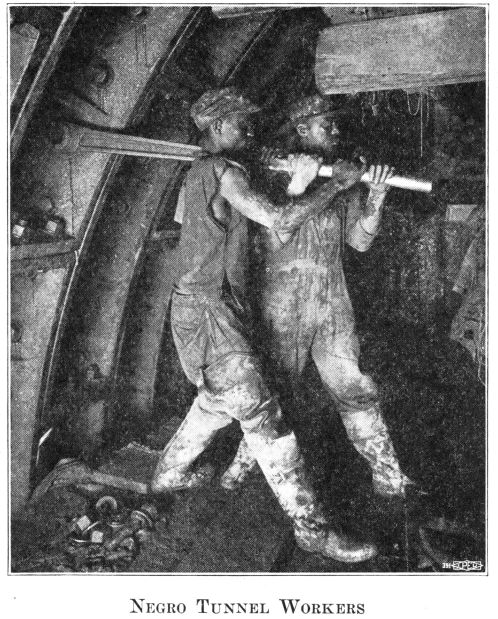

The influx of Negro workers into industry during the last decade has brought the question of his role in the labor and revolutionary movement squarely before the American working class. The expansion of American industry during the world war and the stoppage of immigration created a great demand for labor. The drafting of thousands of southern Negroes into the army intensified the racial antagonism south of the Mason and Dixon line, tore them loose from their feudal environment, and gave them an immensely broader outlook. Increasing persecution in the south and the demand for labor in the north brought hundreds of them into northern industrial centers into contact and competition with white labor. Chicago, Pittsburgh, New York, Boston, Gary, Minneapolis and St. Paul, Detroit, Cleveland, Buffalo and Toledo in the industrial east and middle west immensely increased their Negro working class as did cities lying halfway between north and south like St. Louis, Kansas City and Cincinnati.

Chicago is fairly typical of these industrial centers.

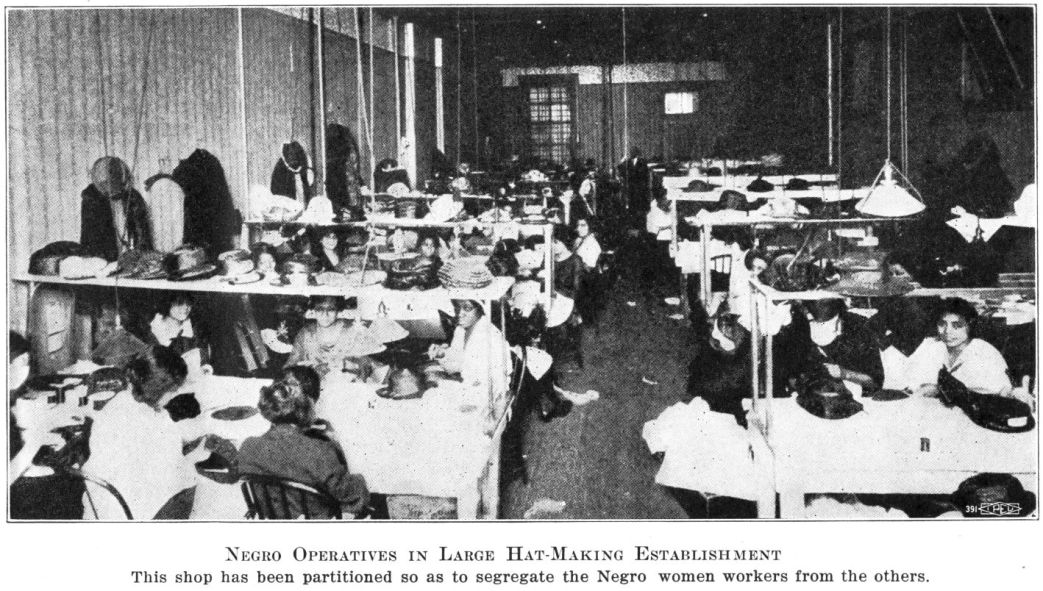

In sixty-two Chicago industries comprising box-making, clothing, cooperage, food products, iron and steel, tanneries and miscellaneous manufacturing, from which statistics were secured, the number of Negro workers increased from 1,346 in 1915 to 10,587 in 1920. The number of Negro workers therefore multiplied approximately eight times in the five-year period.

In forty-seven non-manufacturing industries in Chicago, employing 4,601 Negro workers in 1915, there was an increase to 8,483 in 1920, a 50 per cent increase.

In Chicago, concerns reporting the employment of five or more Negroes in 1920 and altogether employing 118,098 workers, the percentage of Negro workers classified generally by occupation was as follows:

Paper box manufacturing—14 per cent. Clothing—14 per cent. Cooperage—32 per cent. Food products—22 per cent. Iron and steel products (iron foundries)—10 per cent. Tanneries—21 per cent. Miscellaneous: Lamp shade manufacturing—27 per cent. Auto cushion manufacturing—50 per cent. Other industries (manufacturing)—5 per cent.

The percentage of Negro workers in non-manufacturing industries for the same year was as follows (the industries given below have always employed a larger percentage of Negroes than the industrial enterprises proper):

Hotels—53 per cent. Laundries—44 per cent. Mail order merchandise houses—8 per cent. Railway sleeping and dining car service—68 per cent. Miscellaneous (public service, warehouses, taxicabs, telegraph companies, etc.)—6 per cent.

A tabulation of the above percentages shows that in Chicago manufacturing industries in 1920 there was an average of 16 per cent of the working forces who were Negroes, with the quota rising to 23 per cent in the non-manufacturing industries.

According to the figures compiled by the Chicago Committee on Race Relations, the Negro population of Chicago increased from 44,103 in 1910 to 109,594 in 1920—an approximate increase of 250 per cent. The number of Negro workers increased from 27,000 in 1910 to about 70,000 in 1920. The increase in the percentage of Negro workers to Negro population in 1920 as compared with 1910 is undoubtedly due to the influx of Negro workers without families and consequently better able to leave the south.

Migration North

Chicago is the heart of industrial America and from these figures we can gain a good idea of the magnitude of the problem created for the Negro himself—the labor movement and the Workers (Communist) Party by a social phenomenon which is well expressed in statistics showing that already in 1920 about 20 per cent of the workers in Chicago, the greatest industrial center in America, were Negroes.

The influx of Negro workers did not cease in 1920. It continued thru 1921-22-23, and figures made public by the southern state governments show that in this period more than 500,000 Negroes took their scanty belongings and left the southern exploiters to sulk in helpless rage. The Negro has at last found a way to avenge himself on his southern persecutors.

In 1924 the number of Negroes “goin No’th” decreased due to the demand for agricultural labor in the south, where several million acres had reverted to the jungle because of the scarcity of labor.

The figures on lynching of Negroes in the south for 1924 speak volumes—they show a decrease of fifty per cent with a total of “only 19” Negroes done to death; horrible enough, but eloquent in that they show the increased safety of life and improved treatment in the drop from the 1923 total of 38 as a result of the withdrawal by the Negroes of their labor.

Most of the Negroes are in the north to stay and it is not necessary that the migration continue in a flood to bring the problem of the Negro in industry to the attention of the American working class. “The iron march of historical development” has already placed it on the order of business.

The unions of the industrial north and of southern states like Tennessee, North Carolina and Georgia that are rapidly becoming industrialized, can no longer shut their eyes and presume that only in isolated instances will they be called upon to make a decision. One-fifth of the American industrial workers now have black skins. They are in industry and are going to stay there.

II.

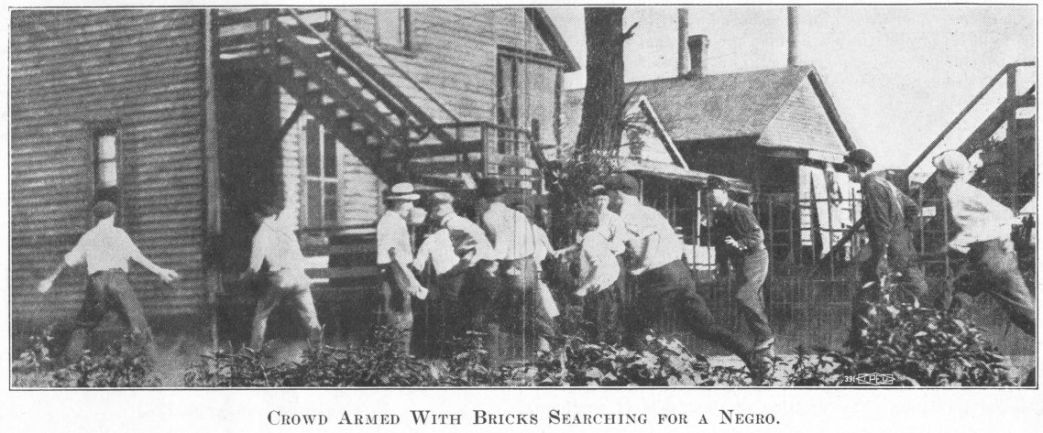

Two tendencies show themselves in the labor movement. One is the blind, dangerous and senseless hatred of the Negro workers, encouraged by the unscrupulous capitalists and carried on by the camp followers of capitalism—real estate sharks, prostitute journalists, labor misleaders and all the carrion crew that live on the offal of the system.

This is the tendency that brought white and Negro workers into conflict in the Chicago race riots in 1919, in which 23 Negroes and 15 whites were killed and 537 persons of both races’ injured.

The other tendency, manifested only by the Communist Party and the most intelligent and militant of the workers outside its ranks, is perhaps best illustrated by the white workers who gave their lives in an armed struggle to protect a Negro organizer of the Timber Workers’ Union from the attack of gunmen of the Great Southern Lumber Company, November 22, 1919.

The heroic stand of these southern white union men shines like a golden star in the bloody history of 1919—the year in which the antagonism between white and colored workers, as a result of the advent of the Negro into industry, reached its climax, expressing itself in race wars, lynchings and dozens of cases of terror against Negroes.

The employers have taken full advantage of the racial antagonism, if this term can be used to describe a problem that has, so far as the labor movement is concerned, an almost exclusive economic basis—the competition of the black workers with the white for the means of livelihood.

That Negroes were used to break strikes in the meat packing, steel and transportation industries, that they are undoubtedly hard to organize in some of the existing unions and are in many cases prejudiced against them, complicates the situation, but it no more proves that the Negro is a natural strikebreaker than the seduction of Negro women by white men proves that the whole male white race is engaged in this pastime.

There are two reasons for the Negro’s distrust of the labor unions, but it is yet to be proved that a much higher percentage of Negroes than white workers remain outside of labor organizations which they have an opportunity of joining.

The fact that in those occupations and industries where there are functioning labor unions and where there are any considerable number of Negro workers, but little complaint of the attitude of the Negro workers is heard, is proof that Negro workers can be organized successfully. In the United Mine Workers of America there are not only hundreds of Negro coal miners but Negro organizers as well; in the Teamsters’ union, the Building Laborers’ union, the Longshoremen’s union—organizations that have something of a mass character, there is practically no color discrimination and none of the racial prejudice found in other unions of the purely craft type.

The inescapable conclusion from the evidence is that when the Negro acquires industrial experience, is in actual competition with the organized white workers, two things happen—the white workers swallow their prejudices in the face of the need for better organization and the Negro worker abandons his suspicion of the labor union and its objects. This brings us again to the two principal reasons for the lack of organization among the Negro workers. They are:

1. The baseless prejudice of the organized white workers caused by

(a) Artificially created racial antagonisms—sexual jealousy fanned by the constant stream of propaganda, belief in the mental inferiority of the Negro, etc.

(b) The belief that the Negro worker is a natural strikebreaker as a result of his use as such in strikes of longshoremen, packinghouse workers, steel workers and other strikes.

(c) The distrust of the organized workers of any new element in the ranks of the working class (the Negro inherits the labor union prejudice formerly displayed against the foreign-born worker).

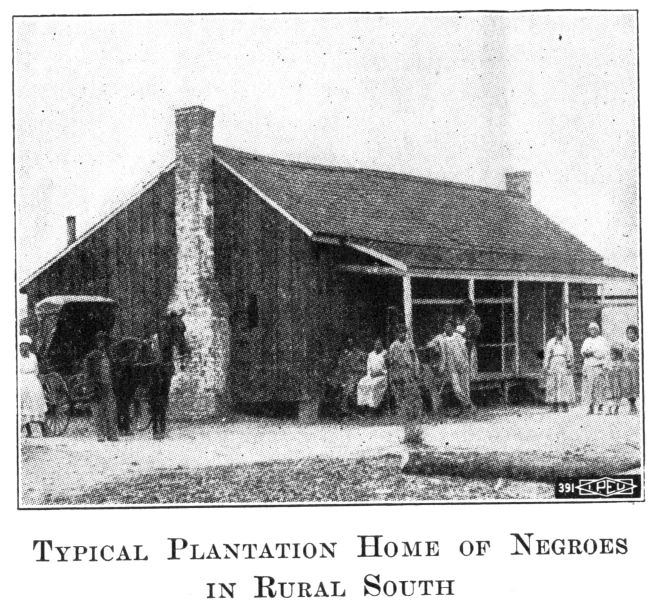

2. The Negro workers coming into industry are peasants with the lack of organizational experience characteristic of peasants the world over and with all of the ignorant peasant’s suspicion of the city worker.

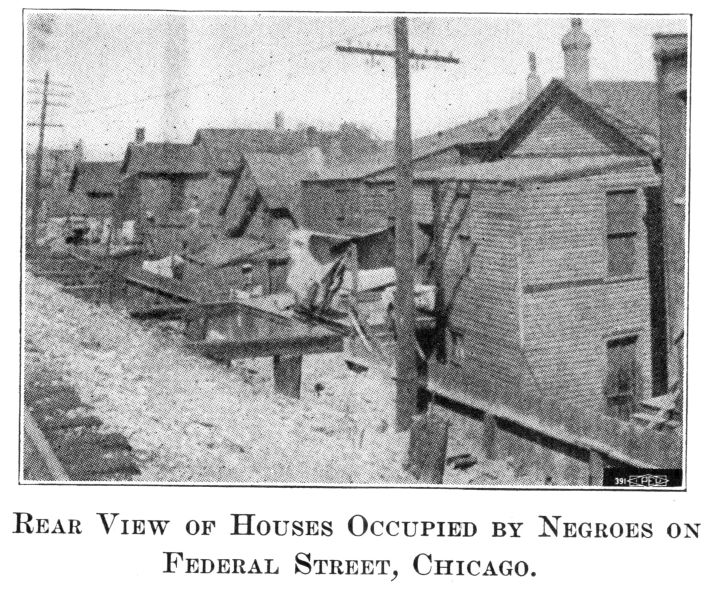

(a) Under the very poorest conditions in industry they have better wages, better food and better living than they have ever experienced before; they must acquire an entirely new standard of comparison before they are interested in unions.

It must not be forgotten in making any estimate of the importance of the first reason given, that of the whole American working class numbering approximately 28,000,000, less than 4,000,000 are organized, even though we broaden the definition of “union” to include many organizations that are not unions at all in the correct sense of the word. The weakness of the labor movement is an important contributing factor to the unorganized condition of the Negro workers.

The second reason is clearly understandable and its primary importance is appreciated more fully when we find, according to a report of the United States Census Bureau entitled, “Negro Population in the United States, 1790 to 1915” (1915 saw the small beginnings of the Negro influx into industry) that of 5,192,535 Negroes in the United States in 1915, who were “gainfully occupied,” 2,893,674 were engaged in agriculture.

In the south, in 1910, 78.8 per cent of the Negro population lived in rural communities and 62 per cent of all those employed were in agriculture. The peasant character of the Negro migrants is therefore clearly established and no one who has had any experience with American farmers and agricultural workers at the time of or soon after their transplantation into industry, will be inclined to blame the Negro peasant who is in process of becoming an industrial worker, for his lack of interest in unions.

If in addition to the well known difficulty of organizing farmers from the northern states, who in bad crop years have established quite a strikebreaking record of their own, we take into account the fact that the agricultural south is comparable to the last years of feudal society in Europe; that in the state of Mississippi as an example, the amount until recently allotted to the public schools was but $6 per capita, we gain a larger insight into the background of the overwhelming majority of the Negroes who came into industry since 1915.

It is useless to rail at workers who are the product of such an environment as this. There must be understanding and the patience which can come only from understanding. Industry itself is the chemist that compounds the antidote for the backward Negro worker, but while the harsh hand of the exploiter is forcing him to drink again and again of the bitter cup of the working class there must be the most energetic direction of the educational and organizational methods at the disposal of the working class.

Upon the white workers rests the responsibility for bringing the Negro workers into the class struggle. When the white workers rid themselves of their ruling class-inspired prejudices, when they see the Negro worker not as an enemy but as an ally, when they realize and acknowledge in tones that can be heard by the Negro workers (and by the capitalists who profit from and foment division of the races), that the Negro workers are necessary for the victory in both the daily struggle and the final victory over capitalism, the task of organizing the Negro workers will be found to be not so difficult after all.

In every union the left wing must carry on a constant and fearless struggle against every manifestation of racial prejudice. The militants must be prepared to challenge the trade union bureaucracy on this issue just as they have on the general questions of policy and tactics of the labor movement and as always the Communists must take the lead.

The work among the Negroes in industry must parallel the work done in the unions of white workers, but for some time it will be of a more elementary character and can only progress as the Negro workers can be shown by concrete instances that the American labor movement wants them as equals and because they are workers.

The Negro workers must be shown that the Workers (Communist) Party is the only party that fights their class and racial struggle uncompromisingly and without counting the cost. They must be shown by actual activity that the Communists are the foe of every enemy of the Negro worker whether he be Negro-hating trade union official or capitalist.

Like the white workers the Negroes are victimized and misled by their middle class. There is nothing more despicable in American life than the Negro business man, the Negro preacher, the Negro politician and the Negro journalist who smirk and grovel to the white tyrants and who teach the men and women of their race that the way to secure concessions and recognition is by servility and meekness, by trying to outdo the white man in smug respectability. It is a matter of record that some of these traitors have sold their followers into industrial slavery by means of fake unions which were nothing but scab agencies.

These two-time betrayers—betrayers of the black race and betrayers of the black working class-must be fought and discredited and this will have to be done by Negro Communists—revolutionary Negro workers who understand both the racial and class issues in the struggle.

The Workers (Communist) Party must train Negro organizers and Negro writers so that as the labor movement is forced by economic pressure to organize the Negro workers, the Negro workers, acquainted by these leaders of their own race with the true role of the labor movement, can become a tower of strength to the revolutionary elements within it.

A survey of those unions that have organized Negro workers affords irrefutable proof that in the unions where black and white workers discuss the ways and means of combatting the tyrannies of the employers, the racial lines become so faint as to be almost invisible. The necessity for common struggle pushes into the background the question of color and it is soon forgotten. Quite aside from the increased economic and political power of the workers that the organization of the Negro workers brings, in the unions is where white and black workers meet in the nearest approach to complete equality.

In the labor unions is where the work of solving the problem of the Negro in industry gets the quickest results and it is there that the problem will be solved as well as it can be under capitalism, while the social-reformers and middle class liberals, “friends of the Negro,” are lavishing wordy sympathy upon him and appealing to hide-bound enemies of the Negro to allow not quite so many lynchings next year.

The task that confronts the American Workers (Communist) Party in organizing the Negro workers and rallying them for the daily struggle and the final overthrow of capitalism side by side with the white workers is no light one. On the contrary it is a difficult and dangerous job.

No one who does not appreciate this fact should be allowed to come within a thousand miles of the work. It is something that cannot be expedited by undue optimism nor can the work be furthered by magnifying to Negro comrades the mistakes of the party and exaggerating its present strength and abilities.

Ill-balanced comrades who know little of the role of the Negro in American industry and less of the labor movement, comrades who appear to think that the whole problem centers around the right of the races to inter-marry, whose utterances give one the impression that they believe the labor movement, a product as it is of historical conditions in America, is a conscious conspiracy against the Negro workers, comrades who without thought of possible consequences would have the party begin immediately the organization of dual independent Negro unions, such comrades as these are useless in this work.

There are two things necessary before we can mobilize any great number of Negro workers for our program. The first is the development of some Communist Negro leadership. The second is a point of contact with the Negro masses.

There are excellent prospects for securing both these fundamental necessities and with the work already under way in the unions the American Communist party will be able to make steady progress in demonstrating to the Negro workers in industry and the whole American working class that it alone has a program for the working class, black and white, that strengthens it in the continual combat with the capitalists and that will bring the working class through victorious struggle, to full exercise of its power by the proletarian dictatorship under which men and women will be judged by what they do and not by the color of their skin.

Sometime this year will be held a conference of delegates from Negro working class organizations. Every effort must be made to have this conference representative of the most advanced group of Negro workers. It will be the first gathering of this kind in America and will establish a center for organizing work among the Negroes in industry.

There must be established as soon as possible a Communist Negro Press as a vital part of the party machinery. The existing Negro press is feeble when it is not actually traitorous.

The problem of the Negro in American industry has taken on an important international aspect. The colonial regions of Africa, where British, French, Belgian and Italian imperialists exploit the masses of Negro workers, are astir. As in America, the war brought the world to the masses of African Negroes. They discovered that the white tyrants had forced them to weld their own chains; that they were expected to fight and die to perpetuate their own slavery.

White supremacy is no longer accepted at the valuation placed on it by the white robber class.

Writing in a recent number of a semi-official publication of the British colonial office, a colonial bureaucrat tells of the changes taking place in the British African territories. He shows that the Negro tribes are holding tremendous semipolitical gatherings at which a high degree of organizational ability is displayed. He writes of the complicated structure of Negro states destroyed by the white invader and tells of the new interest displayed by the Negro masses in the history of their states and customs before the white man came.

He cites their adaptability to modern warfare and modern machinery and warns the British ruling class that new and more subtle methods must be used if the Africans are to be kept within the confines of the empire.

From among the American Negroes in industry must come the leadership of their race in its struggle for freedom in the colonial countries. In spite of the denial of equal opportunity to the Negro under American capitalism, his advantages are so far superior to those of the subject colonial Negroes in the educational, political and industrial fields that he is alone able to furnish the agitational and organizational! ability that the situation demands.

The American Communist Negroes are the historical leaders of their comrades in Africa and to fit them for dealing the most telling blows to world imperialism as allies of the world’s working class is enough to justify all of the time and energy that the Workers (Communist) Party must devote to the mobilization for the revolutionary struggle of the Negro workers in American industry.

The Workers Monthly began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Party publication. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and the Communist Party began publishing The Communist as its theoretical magazine. Editors included Earl Browder and Max Bedacht as the magazine continued the Liberator’s use of graphics and art.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/wm/1925/v4n05-mar-1925.pdf

PDF of second issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/wm/1925/v4n06-apr-1925.pdf