In this penultimate chapter, Nearing synthesizes his experience through an interview with Jean Riappo, Deputy Commissar of Education in Ukraine, about whom he writes: “Among all of the educators that I spoke with in the Soviet Union, none had a clearer vision of the tasks before the schools.”

‘XII. Unifying Education’ by Scott Nearing from Education in Soviet Russia. International Publishers, New York. 1926.

XII. UNIFYING EDUCATION.

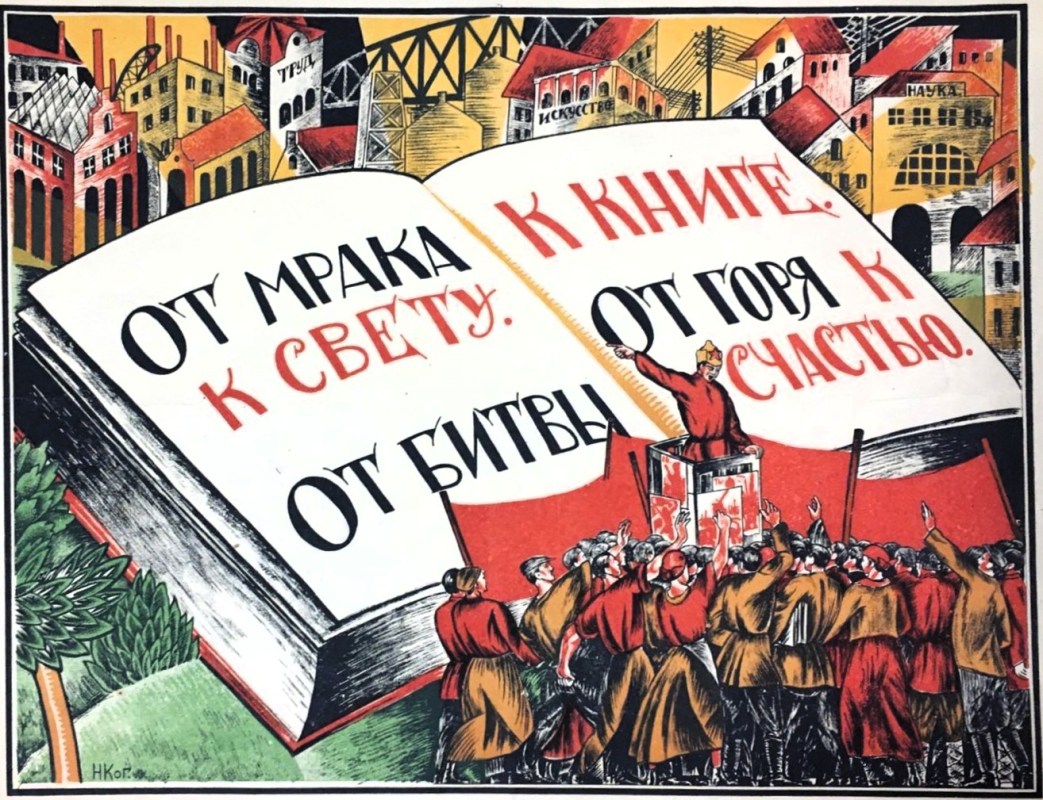

Soviet education has one dominant aim–to enlarge the life experience of the people. Since the vast majority of the people in any modern community are workers, it is upon the lives of the workers that the Soviet authorities are concentrating their educational efforts.

There are three other propositions subordinate to this main proposition: (1) Education must be primarily for children. The child is the educational objective, not the school system. (2) Socially education must prepare the child to function in his present environment, and at the same time to improve it. (3) It must enlarge the vision of life by opening to children the whole field of human culture.

Krupskaya, Chairman of the Section of Scientific Pedagogy in the State Scientific Council of the Russian Republic, puts the proposition in this way: “The new school proposes to serve the great cause of the workers in training the younger generation, in forming men that are fit for life and for collective work.”

Schools must be run for the children. That is their sole cause for existence. Adults must realize this, and if they fail to do so, the children must insist upon their rights.

This is the substance of the message which Krupskaya sent to the Pioneers. “The Pioneer movement produces in the soul of the child a consciousness of human dignity. ‘We are not slaves, we are free citizens,’ declare the Young Pioneers. In the schools where there are Pioneers, they will not permit punishments; nor will they allow the children to be injured, or even spoken to roughly. That is past. When teachers persist in treating children roughly, the Pioneers will wage relentless war on them (feront une guerre acharnée). This struggle is necessary, and it will assist in the construction of the new school, in which the only possible relations between pupils and teachers will be fraternal ones.”

Each part of the program must be explained.

“If the child asks: ‘why is it necessary to study this or that?’ he must not be answered in the old way: ‘that is not your affair; study your lessons without asking questions; your elders know better than you do what must be learned.’ On the contrary, he must be told in careful detail, why these things must be studied, and the explanation must satisfy the child. Only in this way can the school be tied up with life.” (Quotations from a statement prepared by Krupskaya for the Pioneers, and distributed by the Education Workers’ Union.)

These are bold words. Socially they involve an appeal to the children to revolt openly against what they regard as unfair treatment in the school. Educationally they require every teacher to work in harmony with the pupils, and to make the course of study meet their experiences and their interests. Dealing with the second point, the necessity of relating what the child is doing in the school to those things which are a part of the child environment, Lunacharskey, People’s Commissar for Education, writes: “The program of the lower classes begins with matters that may be made the object of simple discussions with the child: the seasons, the conditions that form the daily surroundings of the child, the group that surrounds him, simple notions of the family in which he lives, and of the society of which he is a part. The next year he begins to understand the atmosphere of work in his neighborhood; he receives ideas on the village and the city; thus enlarging the horizon of what he knows concerning his milieu. Leaving the circle of phenomena directly perceptible to his child understanding, he turns to analyze nature: what is air, water, etc. The constituent elements are appraised, and simultaneously the conception of them is raised. The village is taken, not only as the common working unit, but in its formation as a social historic unit. Then they study the neighboring country, the province, and finally the whole nation. Each time the ideas are more abstract, more profound, and in connection with the working process there emerges the idea of social organization.” (Quotations from statements issued by the Education Workers’ Union, summer of 1925.)

Concerning the third point, the broadening horizon that comes with education, Lunacharsky is equally emphatic: “Science is the surest path to Communism, and it is at the same time its principal end. A political revolution has no value, and from it there does not arise human well-being. But well-being itself remains an absurdity, something that does not distinguish men from animals, if it does not lead to a broadening of the intellectual, artistic and emotional life; if it does not augment the happiness that life gives to man in order that he may give it to his fellows. The finest conquest of Communism will be a renaissance of art and of the sciences–this is the most sublime objective of human evolution. Marx told us that the only goal worthy of humanity is the greatest possible enlargement of all human faculties.”

These sayings are quoted from men and women in Moscow. That does not mean that the ideas are localized or isolated in Moscow. They existed wherever I talked with school people. They are not the ideas of any one man or woman. They are the conclusions that have been forced upon the educational authorities in a workers’ state after years of careful testing and experiment.

“We started with the American school methods immediately after the Revolution, but they did not meet our needs,” said Davidovitch N. Horolsky, Director of the Transport Workers’ Educational Department of the North Caucasus. “We have been forced by circumstances to build our own educational system. At the present time we are experimenting with various means that are aimed to make our schools productive and creative. It is in the schools that the children must learn how to live, and they must learn by living.”

Then he told of the struggle they had gone through to adapt the methods and the educational ideas imported from western capitalist countries to the new educational system that the workers were trying to build. At the beginning of the movement, the trade unions of the North Caucasus carried a great deal of the burden. As life returned to normal, after the famine and the Civil War, this burden was shifted to the state. “Russia is still poor economically, but she is making progress fast. Before the Revolution she was poor and ignorant. Now she is poor and determined.”

With great zeal Davidovitch described the work that was being done toward the social education of the children. “In the schools the children are facing and working out their own collective problems,” he said. “In all of our schools, the students work in groups. The Young Pioneers are an excellent example of the kind of social education we are giving.

“The Pioneers are making a new generation. They are interested in the world. They know it and understand it. They work. Many of them are spending from two to four hours a day at some useful occupation. This is a part of their Pioneer training. They are organized. They are disciplined in group activity. They obey their chosen leaders. They will make a great generation of workers.”

This man held a position under the trade unions. He was directing social education. He had been first a worker, and then for years a teacher. He was not repeating phrases that he had read in a book or heard in a speech. His ideas had been hammered out through eight hard years of educational experience under bitterly adverse conditions.

Among all of the educators that I spoke with in the Soviet Union, none had a clearer vision of the tasks before the schools than Jean Riappo, Vice-commissar of Public Instruction and President of the Directing Committee of Scientific Institutions in the Ukraine. Through the Civil War Riappo had held positions of high military authority on one front after another. As soon as the Civil War ended, he went to what he calls the “educational front,” and there he has been ever since.

My contact with Riappo was typical of the experiences that one has in the Soviet Union. I went to his office on Friday, accompanied by an official of the Kharkov Department of Education. Friday is “student day” in that office. From all parts of the city, and from the surrounding region they come, crowding into the office from nine in the morning until three in the afternoon. Other business waits. We were “other business,” so we waited.

The anteroom was thronged with students. Some of them wore the conventional dress of the town. Others wore peasant clothes. There was one figure that stood out among the rest–a big, blond lad of eighteen or nineteen dressed in a goat-skin hat, a long leather shepherd coat and high leather boots. He was part of a delegation of students that had come to Kharkov from their mountain home with a request for improved school facilities in their home community.

The students were admitted to Riappo’s office one at a time, unless they were members of a delegation. Some stayed a minute and some stayed ten. Each one put his case and got his answer.

There was pressing public business. The local legislature was in session; school appropriations were up for consideration, but it was Friday, and there Riappo sat all day, talking with students. On Saturday Riappo went before the legislature with his report and his request for appropriations. Other public business was transacted, but on Friday students were “public business.”

I heard some criticism from educational officials of this practice of receiving students and letting public business wait. Said one man: “These students are a nuisance. They are under our feet wherever we go. How can we get anything done with them around?”

The answer was simple and conclusive: “We are not running these schools to ‘get anything done.’ We are running them for the students–to meet their needs. The least we can do is to put aside one day a week, listen to their requests, and hear their suggestions. They come here in all seriousness to put their cases before us. What is more important than to give them a chance to have their say?”

After the students were through, I had my opportunity to speak with Riappo. He gave me more than two hours.

Riappo had just completed a third book on the educational problems before the people of the Ukraine. The data were at his finger-tips. He had organized his ideas and his material as he organized his armies. The first thing he did, when I sat down, was to ask his secretary for a large piece of paper. On this he drew the plan of his educational campaign, sketching in the details as he went.

“There are three important sectors on the educational front,” he began. “They are the schools, the press and the films. The theatres, libraries, museums and the like have to be considered, of course, but for the moment they are less strategically important than the other three.

“Two principal tasks confront us in our campaign: the education of children who are of school age, and the education of adults who are at work.”

Riappo then turned his attention to the “school sector” and drew on his paper a diagram in four parts, with the following headings:

“I. Pre-school education; ages 3-8.

“II. The mass school; ages 8 to 18 or 19.

1. Social education; ages 8 to 15. The ‘seven year school,’ divided into:

a. A first division; ages 8 to 12, during which the child learns his environment.

b. A second division; ages 12 to 15, during which the child receives a general training in the main subjects that are included in human knowledge.

2. The professional schools; ages 15 to 18 or 19. With these are included factory schools, and other technical schools of high school grade.

“III. Schools for specialists–the officers of the new economic and social order. Higher technical schools of all kinds.

“IV. Institutes, where the generals and directors of the new social order receive their training.”

Then, point by point, he outlined the detail of each of these main headings, with some explanation of the principles that lay behind each part of the program. Pre-school education, he said, aimed to take the children as soon as they were ready for any social life training, and to put them into three institutions, each of which was designed to provide some social opportunity for young children: the day-nursery, the kindergarten and the playground.

“Before the Revolution these institutions existed for the children of the very rich and the very poor. They were never made available for the great mass of the children. We started that work in 1917. The famine and the Civil War stopped us temporarily. Now we are back at the work again.

“There were two great reasons why these pre-school institutions should be made available for all children. The first reason is that children begin to develop social desires at a very early age. They wish to be with other children. This is plainly impossible in many homes, and for such young children the pre-school institutions provide the child with its sole social opportunity.

“The other reason is equally important–perhaps in view of the immediate needs that we face, more important. The wives of workers and peasants in Russia have always been denied social opportunity. The wives of the bourgeoisie had leisure. The wives of the workers and peasants have been tied to their homes through long hours and days and years of unceasing toil. One of the most practicable methods of relieving the women from this toil is to establish institutions where they can safely leave their children for several hours each day. We must do this if we expect our women to take the part they should in public affairs.”

Riappo then turned to the mass school. The plan was to make a school that would accommodate all of the children in the Soviet Union between the ages of 8 and 18. The mass school therefore covered the same ground as the elementary and high schools in the United States.

“The first section of the mass school gave a social education, in seven school years. This was the labor school designed for all children in the villages as well as in the cities. This labor school was divided into two sections: a lower section of four years and an upper section of three years. Soviet educators were concentrating upon the first, or four year section.

“That gives you an idea of how far we still have to go,” Riappo interjected. “We are not deceiving ourselves. It will be at least another year before we are able to provide school accommodations for all of the children in the Ukraine between 8 and 12 years of age. When we have achieved that, we shall go on with the next task–the final three years of the seven year school, and at that point we shall be abreast of the civilized countries of the world— with a place in school for every child of elementary school age. Meanwhile we are continuing with the inadequate equipment we have. It is not good, but it is better than nothing.”

There was no specialization in the labor school. It merely aimed to give the children an all-round acquaintance with life. It provided a thorough social education, and gave a synthesis of the elements of general education.

“The foundation of the social education that the labor school is furnishing lies in the children’s movement—the organization of the children in the classes, in schools and in groups,” Riappo said.

“Perhaps the most important part of this movement is the training they get in hygiene, social organization and in politics through the Pioneer movement.

“The Pioneers were organized in 1923. That year there were about 40,000 of them in the Soviet Union. To-day there are more than 300,000, and the number is growing rapidly.

“The Pioneers are the conscious, intelligent children; those that grasp things quickly, and that are able to act up to that understanding. A Pioneer must take an active part in what is going on about him; he must visit factories and social institutions; he must learn to know the community in which he lives, for he is the builder of a new social order. He declares war on the old society and all of its institutions. It is the Pioneers who will protect what we have won in the Revolution.

“By 1927 or 1928 we hope that practically all of the children in the Soviet Union between the ages of ten and fifteen will be in the Pioneer movement. Thus they will themselves develop the social education they require; they will build from the inside. It will be our duty only to show them what there is to be studied, and to assist them to study it intelligently.”

Riappo then passed to the scholastic side of the labor school. It would not study subjects–arithmetic, spelling, reading, geography. That was the work of the old school, where all of the work was subdivided into special topics, and the children never got any synthesis out of the divisions. Many, even among the teachers, did not get this synthesis.

“Education in the new labor school is built around the themes that are taken directly from the life that surrounds the child. School begins in the fall. The children take the topic ‘autumn,’ discuss it, analyze its meaning, collect leaves and nuts and fruits, organize an autumn fete or festival. For weeks the smaller children think and talk in school about this subject. It is their introduction to education.

“Such things always interest the children. The class work deals with the topics that touch their lives most closely. They talk about the family, the street, the village. Children and teachers plan and work out the lessons together. Each lesson is a part of the general topic they are studying.

“During this process of analyzing the life of the world around them, the children come into contact with three threads that run through all of our problems: Nature; Labor; Society. But instead of beginning the school work by telling them this, we let them work at the problems until they find the threads.

“We have been working with this system for only a few years, but the experience that we have already had convinces us that the child gets far more by this method than he ever got by the old one. As the system is developed, the child will get a better and better understanding of the life about him.

“You will notice,” Riappo continued, “that this system is quite opposed to scholasticism. It is the complex or synthesized system. Under it, the child gets, easily and naturally, an acquaintance with the society in which he lives.”

One of the greatest drawbacks to the introduction of this new system in the Ukraine was the lack of trained teachers. The plan was new. It was still in the making. In order to teach successfully under it, the teacher must not only understand the technique, but the principle as well, and more than all, the teacher must have the desire and the ability to experiment in co-operation with the children.

“Our teachers here in the Ukraine are at least as good as the ordinary,” Riappo continued. “Each of them is expert in one or more subjects, and the village teachers were on the whole well prepared to teach under the old plan. They know mathematics and history but very few of them have any idea of the relation of one subject to another, and a still smaller proportion has any sense of the relation of these topics to the life around them. We aim, in this new education, to begin with life, and to bring in mathematics and history incidentally, in their proper setting. We have given intensive courses to all of our teachers in this new system. This year we are picking out the most promising among them and giving them a full year of special study in educational method. We expect them to be the propagandists for and the leaders in the new system.”

Riappo did not say anything specific about the last three years of the labor school. It is one of the most difficult educational problems they face, and they are still busy with the first four years. Labor schools were training grounds for social and general knowledge. They were related to the local environment, but in them all of the children received practically the same general preparation for life. Specialization began with the professional schools.

“We plan to have a professional school for each chief department of work,” Riappo explained. “In these schools we propose to train qualified workers. Before we get through, every boy and girl in the Soviet Union will receive this special training as a part of his school course, and will thus prepare himself for his special work in life. Whether in industry, in agriculture, in health work, in art, or in any other field, we intend to have each worker with at least a minimum knowledge of the principles that lie behind the specialty in which he is engaged. The professional school is thus the latter or upper section of the mass school. All of the children are expected to take the work it offers. “Under the old system there was a dualism in education. There was a classical school and a specialist’s school. In the classical school pupils acquired knowledge often for its own sake. They were the knowers. In the specialists school they acquired a technique. They were the doers. These two groups of pupils belonged to two classes in society. The knowers were the members of the upper classes. The doers were members of the lower classes. This was a form of education fitted to a society that was organized on a basis of class distinction.

“Our society no longer has classes. We are aiming to give every pupil that comes to the school the kind of a training that will best develop his faculties. We do not ask: ‘From what social class do you come?’ but ‘What talents do you possess? Having found the answer to that question, we provide the kind of training that will give those particular talents the greatest opportunity for social usefulness.

“That is, we are trying to combine the knower and the doer in one person; to unite theory with practice. This education is possible only where there are no social classes. Its basis is social monism–a unified, classless society.

“We are under no obligation to separate knowing and doing because we have abolished class differences. Knowing and doing belong together in a rational life. We are combining them, and training qualified men and women by giving each a general and a specialized education. Such educational monism is possible only in a one class society, and in such a society, no other system will work.”

Riappo then took up the struggle that they had been making to establish professional schools in the Ukraine, and the success that had attended their efforts. “Before the Revolution,” he began, “there were about 50,000 children in the gymnasia (high schools). Most of them were the children of the well-to-do. The children of the workers seldom reached that point in the schools. During the year 1924-5 there were 72,000 children in the professional schools of the Ukraine. This fall (1925) we have registered about 92,000. Of these, 23,000 are in factory schools. Most of these children are sons and daughters of the workers.

“Now turn to the rural schools. Before the war there were 74 agricultural schools of professional grade. Most of them were hardly worthy of the name. They never gave any real agricultural training. To-day we have 192 such schools, with 42,000 desyatines of land, with agricultural machinery, and with the necessary equipment for training men and women to go back and carry on scientific farming.

“But many of the young people from the villages cannot get away for the whole year, and so we are opening 270 winter schools this year, for an intensive four months’ course. These schools will train the peasants in some special lines of agricultural economics.”

Ukranian industry was growing rapidly, Riappo pointed out. There was a constantly increasing demand for specialists in all branches of manufacturing, transport and agriculture. There would be 23,000 students turned out by the technical schools this year, but that was not enough to supply the demand. The next few years would undoubtedly see a great industrial expansion, but this presupposed a school system that could provide the necessary trained personnel.

Regarding the higher technical schools–the third division of the Soviet system, Riappo spoke with particular eagerness. This was the field of his special interest. It was in these higher technical schools that he believed the success of the Soviet experiment lay. He said:

“Before the Revolution the dualism in our educational institutions was complete. The universities presented general culture and pure science to the children of the ruling class. From the institutes came trained specialists who lacked the general and theoretical knowledge that the universities were giving to someone else. The result was two men, and neither qualified to be useful in the world. The university student had no specialty, and the student from the institute lacked theoretical knowledge.

“After the Revolution we found that the universities here in the Ukraine were insisting on a perpetuation of this academic dualism. They were not capable of adjusting themselves to the new social period which we were entering. Consequently, in 1920, here in the Ukraine, we passed a law abolishing the universities. We acted just as the French Revolution acted in 1792 when it liquidated 22 universities because they were protecting the old order.

“Because of the part that I played in that campaign, I am called by some in Russia the barbarian that is ruining education. I am not ruining education. I am helping to lay a sound foundation on which alone the new education can be built.

“During the last five years I have been insisting that a degree from a higher educational institution should stand for practice and for usefulness to the community—not for pure science. Science is not an end. It is an instrument, a tool, that we must use in doing what we need to have done.”

Next, Riappo discussed the economic basis for the training that he was advocating. “These higher technical schools,” said he, “will train officers who are capable of directing activities on the labor front. There will be schools in each field, and from them will come men and women capable of getting practical results.

“Under the old regime there was a highly trained engineer at the head of an undertaking. Under him there was a mass of workers who were so ignorant that they could not even read and write. We propose:

“Scientific engineers;

“Trained technicians;

“Educated workers.

“This is the economic foundation for the dictatorship of the proletariat. Who should occupy the responsible posts in this organization? The peasants and workers who have created the system, and in whose interest, and by whose authority it is being perpetuated.

“Foreign newspapers blame the Soviet authorities because they keep the bourgeoisie out of the schools. The children of the bourgeoisie are going to these schools in order to acquire the knowledge that will enable them to overthrow the peasants’ and workers’ government. Why should we train our enemies? Of course we do not let them into the schools while there are not enough places for the children of the workers and peasants. We are engaged in proletarianizing the schools just as we have already proletarianized the industries and the government.”

In support of this contention Riappo cited the social position of the students in higher educational institutions of the Ukraine during the past decade. In 1914, 64 per cent of the students were from the aristocracy and the upper bourgeoisie; 30 per cent were from the little bourgeoisie; 4 per cent were from the peasants, and 2 per cent were from the workers. The March revolution smashed the aristocracy and the upper bourgeoisie, but it put a new bourgeois class in power, and in 1920, 72 per cent of the student body of the higher schools were from the little bourgeoisie.

“That was the new danger. We had beaten the old order in the factories, in the government and on the military field. Now they were proposing to come back into the schools, and, while keeping out the children of the workers and peasants, secure the training necessary to defeat us in a later struggle.

“That was the danger, and we met it by making provisions under which students who come to our higher schools must have a recommendation from some organization of workers or peasants. Next year we shall be able to fill all of our higher schools by students going directly from the lower schools. The danger of the old ruling class again getting control of the higher schools is practically passed.”

Riappo next took up the fourth group among the Ukrainian schools–the institutes. There were now thirty-five of them in the Ukraine, he said. Each was a special working laboratory in some branch of science.

“The students in these institutes are the pick of the higher technical school student body. They are the most promising ones. They will be the generals. They will command on the field of Soviet economic and social life, and there win the fight against the capitalist system of the whole world.”

Men and women who enter these institutions, Riappo pointed out, worked for about eight months of the year in the institute. During the other four months they worked in some mine, factory, or other department of industrial or social life that represented their chosen profession.

“This,” Riappo said, “is our substitute for the former vacation at an aristocratic summer resort.

“When a student gets through school now, he does not get a diploma. Instead, he goes to work for one or two years at his calling. Then, if he proves his worth, he is granted a certificate of proficiency.

“Again and again,” Riappo continued, “your papers have said that the Bolsheviks were destroying science. Look around at the work that our young men and women are doing in the scientific laboratories. It is not necessary that a laboratory should be in a university. Chemical laboratories belong in chemical works, and mechanical laboratories in the centres of mechanical industries. In the more advanced countries each great industrial plant is building its own laboratories. That is the logical line of development, and we are following it. To these laboratories, as students and as assistants we send our most promising students and workers. This is our method of preparing scientific experts.

“Combined, these laboratories (institutes) make up the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences. All of these scientific centres do not develop with equal rapidity. Differences in personnel and in timeliness make differences in their rate of progress. Some of them already show great promise: Bio-chemistry, Physics, Geology, Labor. Our ideal is the Pasteur Institute in Paris. But here we are aiming to do for all fields of science what the Pasteur Institute has done for one field. We have not destroyed science. Quite the contrary, we are making real scientific work generally possible by providing the opportunities for carrying it on. What we have destroyed is the dualism between science and scholasticism. We have put science to work.”

This, Riappo explained, constituted the school system as far as the children were concerned: the mass school, consisting of the labor school and the professional school; the higher technical schools, in which the officers of industry are trained; the institutes, for training the directors of community life. He then turned his attention to the work of adult education.

“The field of adult education is simpler,” said he. “We number our illiterates by millions. These people never had any systematic training of any kind, unless they got in when they learned a trade. Most of them are peasants, and with us farming is neither scientific nor systematic. To these people we must give political and technical training.”

Riappo distinguished four distinct tasks in the field of adult education: (1) the liquidation of illiteracy; (2) providing special technical training for those capable of absorbing it; (3) liquidating the stranglehold of the old religion on the masses; (4) liquidating sectionalism and nationalism. To each of these tasks the educational authorities were devoting themselves, just as specifically as they were devoting themselves to the education of school children. The means were different, however.

The first, and probably the most important means for adult education was the club. These clubs were being established in the cities by labor unions. They were being established in the villages by village councils as centres of village life and culture. They included reading-rooms, libraries, meeting halls, moving-picture machines, social rooms, class-rooms and the like. Already there were 6,000 such clubs in the villages of the Ukraine, and the number was growing rapidly. Said Riappo: “As a result of this club work, supplementing that of the schools, by 1928, every person in the Ukraine between 10 and 35 will be able to read and write.”

Technical education for adults was of two kinds: political technical education and mechanical technical education. Night schools and technical schools for adults were supplying the mechanical technical education.

“There are two other agencies of immense importance,” Riappo continued. “The press and the cinema. Both are being used in the effort to spread enlightenment among the adult workers who have never had school opportunities.

“The press of the Soviet Union is turning out books by the thousands–cheap books in every field of social and natural science, literature, poetry, drama. These books are being sold in the cities and villages, and they are in thousands of reading rooms all over the Ukraine.

“Then there are the newspapers. We plan to have at least one newspaper in every community. We have already reached this goal in the larger centres, and we are now working toward it in the smaller ones. You have seen our magazines. They cover every field, and they already have a wide circulation.

“All of these forms of printed matter are under government control. All are being used consciously for the purpose of educating the masses, just as the schools are used for the education of children. Within three years we shall have covered every village in the Ukraine with literature: that means a small library, a reading room where newspapers and magazines are on file, and some provision of books and literature for all of the schools.”

Last, but in one sense the most important of the means of adult education, was the cinema. In the Ukraine the cinema as well as the theatre was in the hands of the government.

“Theatres succeed well in the cities,” said Riappo, “but they do not go in the villages. Play production on a professional scale is too costly; talent is limited. The cinema works in the villages. It is far more effective than in the cities.

“Our Cinema Trust is poor. In 1924-5 we could afford only 130 sets of apparatus. We kept these in the villages through the year, and they yielded us a profit of over a million rubles. We have put this entire profit into new equipment. This year we have 1600 sets of apparatus. Again we expect to make a profit, and again we shall turn this profit into new equipment. Within a few years we shall have a cinema apparatus in every village. After work and in the winter season the peasant will be able to go to the village club, and for a trifling admission fee he will see the world go past his door. As a part of every exhibition we have an educational film. We expect that this will prove one of the most important factors in the enlightenment of the adult peasant.”

Riappo then cited the very great increase in the budgetary provisions for education. “We made our first local and central budget in 1922-3,” said he. “It was a feeble beginning. This year our total budget is over five times what is was in 1922-3. In this new budget, 48 per cent of the central government appropriations and 30 per cent of the local appropriations are for education. Salaries of village teachers are nearly four times what they were in 1922-3; salaries of professors in higher institutions are more than four times as high.

“We were pessimists in 1922-3. We did not see how we should be able to advance. But we persevered. Now we have demonstrated our ability to go ahead on the industrial field; on the education field; on the field of social reconstruction. We are moving forward rapidly. Workers in the schools see their salaries and their conditions of work improving month by month. They now believe that they have a unique educational opportunity. Even some of the old professors in higher institutions, who felt that everything was lost, are waking up to the fact of this new life. Our state is rich in iron, coal, water-power, sugar. Germany and Czecho-Slovakia, with their great technical development, are our near neighbors. One day, economically, we shall leap instead of stepping. This is the promise of our economic development. When that day dawns, education will move ahead as rapidly as industry.”

Riappo is a propagandist, of course. He has a cause in which he believes whole-heartedly–the education of every person, old as well as young, in the Ukraine. He has a method for accomplishing this result. In the working out of this method he has availed himself of the entire educational experience of the modern world, and to this borrowed knowledge he has added nearly a decade of experimentation in the Soviet Union. Few precedents hamper him and his fellow workers in education. They are building from the bottom. The result of their labor promises to be an educational system that is as unique in its structure as it is prophetic in its method.

Foreword, I A Dark Educational Past, II The Soviet Educational Structure, III Pre-School Educational Work, IV Social Education—The Labor School, V Professional Schools (High Schools), VI Higher Educational Institutions, a. Higher Technical Schools (Colleges), b. Universities, c. Institutes, VII Experiments With Subject-Matter—The Course of Study, VIII Experiments With Methods of Instruction, IX Organization Among the Pupils, X The Organization of Educational Workers, XI Higher Education For Workers, XII Unifying Education, XIII Socializing Culture.

International Publishers was formed in 1923 for the purpose of translating and disseminating international Marxist texts and headed by Alexander Trachtenberg. It quickly outgrew that mission to be the main book publisher, while Workers Library continued to be the pamphlet publisher of the Communist Party.

PDF of later edition of book: https://archive.org/download/in.ernet.dli.2015.123754/2015.123754.Education-In-Soviet-Russia.pdf