Before Rupert Murdoch and Fox, there was William Randolph Hearst and his media empire devoted to cultural vulgarity and political reaction. A special target of Hearst were the government programs won by unemployed artists during the Great Depression. In many U.S. communities, the art created in that period is the ONLY public art ever created. Public art was not just an anathema to Hearst, but a threat to his mission of keeping Americans ignorant and their expectations low, so he went to war against the Artists’ Union. They went to war back.

‘The Artists Fight Hearst’ by Alfred H. Sinks from New Masses. Vol. 17 No. 2. October 8, 1935.

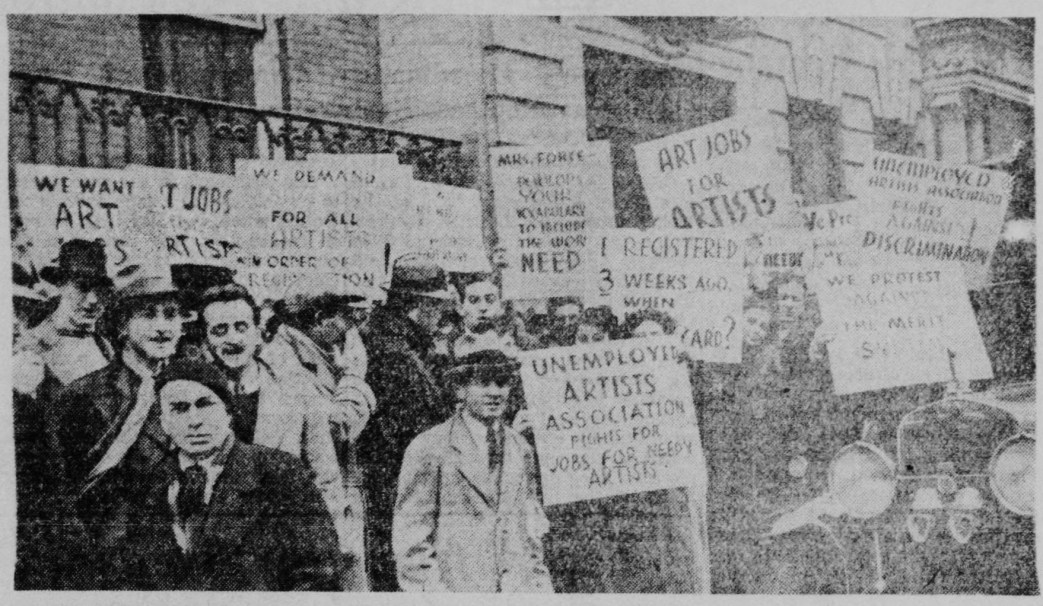

IN the summer of 1933 a small group of artists was employed for the work of copying anatomical drawings at New York University under the then Emergency Works Bureau. Among this group there awakened a consciousness of what was happening to thousands of unemployed artists as the crisis deepened. They formed the Unemployed Artists Association; object, to secure for all artists a chance to work and earn a living within their chosen field.

The U.A.A. made contact with schools, societies, galleries, museums, patrons of art, politicians. Its campaign was broad but intensive. Two delegates were sent off to Washington. An intensive drive for government jobs for unemployed artists was fought through November. In December the P.W.A.P. (Public Works Administration Project) was announced from Washington. This was the first substantial victory for organized artists.

The jobs provided by the early P.W.A.P. showed a tendency to fall to a few favored artists whose wealthy patrons wanted them subsidized at the public expense but the growing U.A.A. continued to press its militant demand that artists be hired on the basis of need. Frightened by the massing of aroused artists before the Whitney Museum, the directress, who was also directress of P.W.A.P., ordered the building closed and took a hurried vacation. Cops paraded before the building on Eighth Street and Mrs. Whitney’s collection gathered dust behind shuttered windows but the demonstration went on.

The P.W.A.P. was not an unqualified success. Out of 3500 artists registered for jobs only 857 were taken on. But it was a step in the right direction and while the P.W.A.P. was still operative, mass pressure directed by the U.A.A. against the city officials brought the College Art Association into being. About 300 more jobs opened up. But there was still a great deal of ground to be won.

Mass demonstrations grew ever larger and more militant. Mass action by artists had its dramatic aspects. The bourgeois press found it good copy. White-collar workers in other lines took courage from the artists’ repeated victories. The aroused painters and sculptors were becoming a shock brigade for a battling arm of class-conscious white-collar and professional workers.

Politically activized though they had become, the members of the Unemployed Artists Association did not forget that they were artists. Toward the working masses of America they had a cultural as well as a political responsibility. The Artists Committee of Action came into being with the specific task of developing media for mass distribution of artists’ work. Together with the Federation of Architects, Chemists, Technicians and Engineers, they developed the Municipal Art Center Plan and presented it to the city administration. The mayor flank-attacked by appointing a Park Avenue Committee of One Hundred to consider a plan for a Municipal Art Center, for the conception of which he modestly took all credit.

IT was inevitable that in the course of their struggle on behalf of all artists the U.A.A. should become more and more conscious of its role in the class struggle. They came to see themselves not as isolated individuals but as an integral element in the broad working masses of America. In May, 1934, the U.A.A. became the Artists Union, with a broader, social program. The A.C.A. amalgamated and the new union absorbed its functions.

The enlarged program was pushed with a deeper consciousness, with a new vigor. The passing of summer saw the membership jump from about 100 to more than 400. By January, 1935, more than 900 artists had taken out union cards and at the present writing there are some 1,400 members in New York City. The effectiveness of the fight for jobs for unemployed artists is reflected in the fact that in the present W.P.A. set-up, the appropriation for art projects is larger than that assigned to any other white-collar group. The artists have become the spearhead for the whole white-collar movement.

It is not surprising that a working-class movement of such strength should draw the fire of one of the arch enemies of all such movements, William Randolph Hearst. In the latter days of August, one of Hearst’s trained faecevora was sent out with instructions to “get the artists” on W.P.A. and the Artists Union.

The unenviable assignment fell to Fred McCormick of The Sunday Mirror. Understandably, McCormick gave the organized artists a wide berth. He went straight to those Lethean Isles in Greenwich Village where the pale wraiths of a dead culture do their danse macabre in the artificial moonlight of a few guttering candles, trying to keep alive the old, bohemian tradition. Run with an eye to the tourist trade, these haunts had always been the ripest of fruit for the Hearsts and the Macfaddens.

The traditional habitat of artists, Greenwich Village has furnished yellow journalism and drug-counter literature with a purple setting for some of its most prurient fabrications. To a mind conditioned by reading Hearst, the word “artist” suggests with beautiful simplicity the word “models.” And in the Hearst lexicon “models” has a very lively connotation. Throw in a dash of this sort of offal and you have the seasoning of a Hearst front-page story.

A Hearst run story need not hold much water. so long as it’s hot. And whether its object is the white-slave traffic or this season’s most popular rapist and murderer or a political opponent, the technique never varies. All reporter McCormick had to do was down to the Village, pick up a little cheap color and two or three names to give a spurious timeliness to the “Village stuff” he dug out of the Hearst files; then shovel up the whole putrescent mess and dump it in the lap of the Artists Union. He did just that.

The tone of the article was sneering. The words “artist,” “art,” even the modest mono-syllable “work” appeared in quotation marks. A stenographer was found who would say of the artists: “They’re a bunch of loafers, and don’t deserve a bit of help.” Another Villager discovered by McCormick gladly obliged by calling the artists “just-BUMS.” But the all-time low in wise-cracking invective was struck by McCormick, who himself coined the expression “hobohemian chiselers.”

On the Thursday after the article’s appearance, a delegation from the Artists Union called on Kenneth McCaleb, editor of The Sunday Mirror. Using McCormick as his messenger boy, McCaleb sent out word that he would be willing to talk with a small delegation from the Artists Union the following Thursday at four-thirty. The members of the delegation let McCormick know they would keep the appointment, thanked him and left.

But on the intervening Sunday the second article in The Mirror series appeared, and the hour of the appointment found several hundred artists parading outside the Hearst building in a mass picket line. They carried banners which read: “Don’t read Hearst! He lies!” And their chanting voices could be heard above the noise of traffic.

Hearst hoodlums tried to break up the demonstration by bombarding the pickets with missiles from the upper windows of the building. Police were on the spot, but they made no move to stop the bombardiers, though a number of pedestrians, as well as pickets, were struck. However, after it became apparent that the line would hold fast in spite of the barrage, the cops decided to take action. They rushed the line in wedge formation, breaking it up into groups and preventing the line from moving. The chief police witness later testified on the stand that the artists were arrested because they refused to keep moving, but insisted on stopping and collecting in groups on the side- walk! Forty-seven out of the two hundred in the line were arrested.

The forty-seven were all that the cops. could cram into the freight entrance of the building, where they were packed into the suffocating enclosure behind the big, steel fire doors.

From there they were transferred in small groups to the Fifty-fourth Street police station where they were thrown, men and women together, into the crowded bull-pen with pick-pockets, prostitutes, vagrants, dope fiends and drunks. Among the artists were some veterans of another picket line, the one of August 15 before the office of the College Art Association, when eighty-three were arrested. Others were “first offenders.”

Magistrate Louis Brodsky heard the case. So did two Hearst reporters, though the Hearst papers never carried a line on the trial. The police witnesses contradicted one another’s testimony. They seemed to find it very difficult to pick the offending artists. from among the crowd of faces in the court-room. Two or three of their selections had not been anywhere near the picket line. One did not even know where The Mirror office was located. The case of the people was a howling burlesque.

The judge found ten of the defendants guilty. Four of the ten had not even been identified in court. The judge made the others promise to be good.

The fight goes on…September 15, The Mirror extended its attack to the actors and theater workers on the Drama Relief projects. Writers and poets are next in line as Hearst continues to whoop up his Red scare against the whole white-collar phase of W.P.A. The Artists Union is carrying the brunt of the battle. Workers on relief projects will have to fight the Hearst type of slander as well as wage-cuts and other forms of exploitation as the approach of a presidential election year brings on an ever sharper crisis among the warring factions of bourgeois politics. The fight of the Artists Union calls for the support of all white-collar workers, both employed and unemployed.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1935/v17n02-oct-08-1935-NM.pdf