There has never been a time where the labor movement was not faced with dramatic shifts in technology in existing workplaces, and the emergence of whole new industries. How the movement responded has always been a ‘life or death’ question. Here, Harvey O’Connor surveys the new aviation industry that developed so dramatically around the First World War, the unions involved in the various, then widely dispersed, plants, and suggestions on the urgent need to organize the industry before it ‘trustifies’ like auto and becomes a much harder nut to crack.

‘Union Label Wings’ by Harvey O’Connor from Labor Age. Vol. 18 No. 2. February, 1929.

Machinists in Key Position

Twenty-five years ago two brothers made a contraption that hopped painfully 100 yards in the first man-carrying airplane flight in history. Today 10,000 planes are in the air, is it fanciful to foresee 25 years hence—millions of workers building and servicing wings for America?

In the first quarter century, the plane has developed from a clumsy, dangerous collection of lumber, cloth and piano wire into a trim, dependable, safe transport device. In 1903 a simple woodshed was hangar, workshop and office for two men who constituted the aviation industry of their day. Now 25,000 men are employed directly in the building and servicing of planes and another 50,000 in fashioning the raw materials, financing, selling and exploiting the product. Each year sees aviation thrusting forward, doubling previous records. Five thousand planes were made last year, 2,000 the year before, probably 10,000 will be turned out this year.

To the unionist, this astonishing growth of motored birds into a major service, vying with speeding train and perfected automobile for mastery of transport raises a fundamental problem. Are the men and women who weld duralumin into wings to be members of a powerful aviation workers union or aircrafts federation, as in the railroad industry? Or will company unionism and industrial feudalism, as in non-union industries, dominate the field, binding workers hand and foot to their bosses? That question must be faced now, when the industry is coming out of its infancy into maturity.

The perfection of the helicopter or some similar device enabling planes to rise and descend within the space of a few yards, is the only obstacle now to mass production of a transport medium whose speed and flexibility will relegate the train to heavy freight service and the auto to trucking and taxi transport. Even now a plane can be bought on time payments, $500 down and so much a month, for as low as $1,800. The principles of air navigation and plane construction are so well applied that a plane flying 150 miles an hour is in many ways safer than an auto making 20 miles.

A pilot can step from his cockpit, while flying, releasing all controls, without danger. Would an autoist care to drive from the back seat?

85 Cents An Hour.

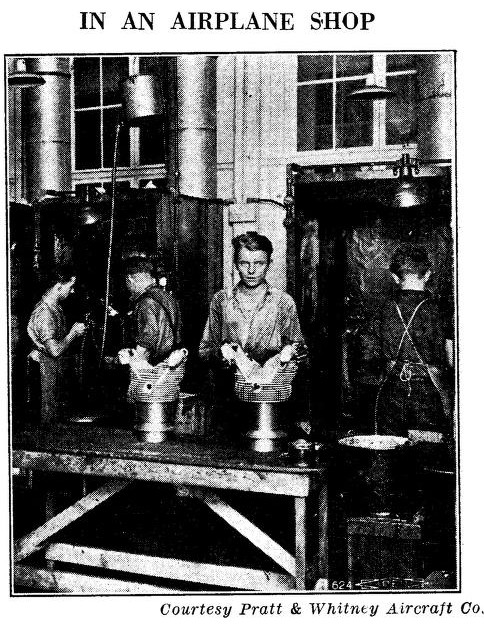

Although this newest of the industries is raining profits from the air on its manufacturers and financiers, its workers fare little better than those in other transport lines. A skilled tool and die maker, bringing into the airplane shop 10 to 30 years of all around machine shop practice, works for 85 cents an hour. Semi-skilled mechanics make 50 to 85 cents. Women working on the fabric coverings of wings get as little as 35 cents.

Unionism among them is non-existent. Unionism among the manufacturers, selling agencies, air transport companies is well-nigh 100%. The industry’s owners and profit-takers boast of their Aeronautical Chamber of Commerce, embracing 95% of manufacturers. Other organizations cater to specialized needs for cooperation.

For the workers, the Pratt & Whitney, Wright and Curtiss company unions are good enough. Don’t they throw a picnic once a year, and don’t they publish employe papers, picturing John Henry’s baby and Jennie Little in a bathing suit? Group insurance trying the engine builders to their bosses, is a strong feature of these company unions, but how they shy off from the mention of wages or collective bargaining!

Time to Act

If labor is on its toes, the airplane industry can be organized now, before it trustifies and builds up Chinese walls against unionism. Indeed, labor could hardly select a more vulnerable point of attack on superprofits. Strikes in the three big engine plants could tie up the entire industry; organization of one essential craft could force employers to permit unionization of every worker; thousands of men who have been members of trade unions are employed in engine and plane shops; unemployment is not so intense as in other industries.

Johann Dietrich, over from Germany but two years, works at his lathe in the plane shop, wondering why there’s no union in America for him. In the old country the Metallarbeiter Verband, embracing all workers in metals, was his union, defending him against wage cuts, stabilizing employment, backing his demands for better conditions. Here in America no union asks him to join.

John Smith, expert machinist, who carried a Machinist’s card for years before and during the war, is now an “ex.” “Sure, a union would be a great thing here. We could line the boys up. But where’s the union?” he asks.

Others, still card carriers, wonder how a group of unions can make an effective appeal in plane shops. Should machinists, pattern makers, molders, electricians and a dozen other unions make individual appeals? Or can they all get together, as they did on the railroads, into a federated shop crafts? Better yet, can the Metal Trades either yield all jurisdiction to one union or throw their forces together for one united metal workers or airplane workers union?

Such is the picture of confused thinking and paralyzed action in a typical factory on Long Island which turns out hundreds of planes each year for the navy.

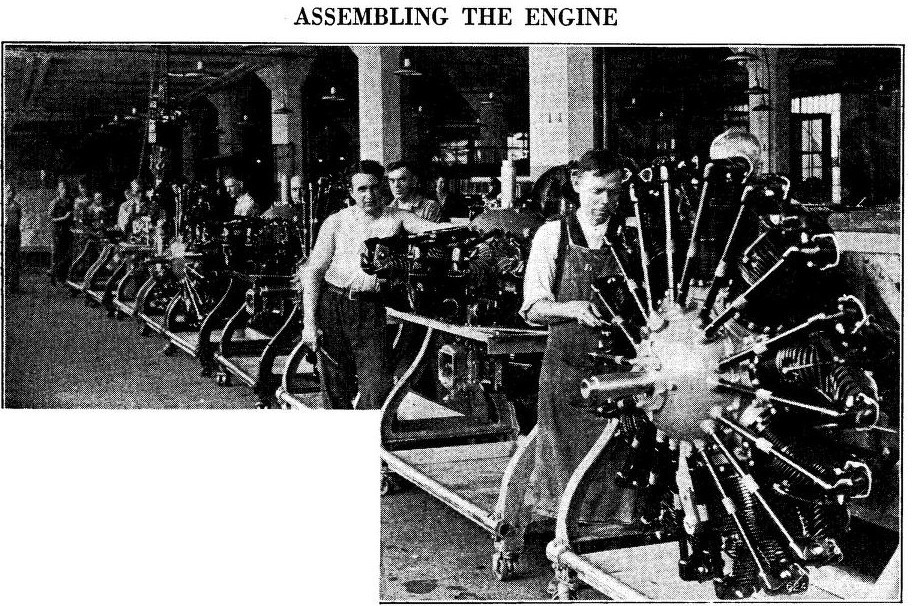

Which is the key craft in the engine and plane-assembling branches of this new industry? The machinists, undoubtedly. Their numbers predominate in Pratt & Whitney’s New Haven shop, in the Wright plant at Paterson, in Curtiss’ Buffalo factory. In the plane shops, making tools and dies, laying out metal frames, welding together wings and fuselage, it is the machinist—especially in his role of welder—who is the key man. The Machinists’ Union, with its recently proclaimed jurisdiction over all welding, is at the crossroads of approaches to labor organization. Important also are sheet metal workers, electrical workers, carpenters.

What have the unions done? Very little, it must be admitted. The metal trades unions, still shellshocked from the terrific open shop offensive of 1921-22, find their own immediate problems too great to warrant exploration or invasion of this fertile unorganized field. The A.F. of L. executive council at an Atlantic City session last summer, issued an apocryphal statement that it was studying the industry. However, no report was submitted to the New Orleans convention to indicate that any conclusion had been reached from the study—if any. The Machinists’ Union would like to take the initiative, but it finds railroad problems all-absorbing for the present. This organization has made inquiries into the industry and exhibited a desire to take further interest.

The Independent Auto and Aircraft Workers’ Union seems to have been guided by good intentions in including “aircraft” in its title, but the Detroit Employers’ Association has been too aggressive to permit it to go afield.

A union survey of aviation will show significant facts to guide an organization campaign:

The industry is decentralized geographically and will remain so for a number of years, if not permanently. The product is so costly and the raw material so light that transportation charges are not exorbitant. On the other hand, the finished product, boxed in huge crates, presents a high shipment expense. Thus we see Wichita, Kansas, as the “aviation capital of America.” Distant Seattle has the Boeing works—one of the bigger units of the industry. A hundred firms are active in the Los Angeles, Detroit, Buffalo, and New York industrial regions.

Aircraft Mergers.

Aviation, however, is concentrating under the control of a few major financial interests. United Aircraft and Transport, just merged, is the biggest unit in the industry. Controlled by National City Bank interests, it comprises Pratt & Whitney, makers of the Wasp and Hornet motors; Chance Vought Co., Long Island City, makers of the Corsair and Amphibian military planes; Boeing’s of Seattle, makers of transport and mail carriers; and both the Boeing and Pacific Air Transport, in control of western mail, express and passenger transportation. Thus the merger is represented in the three major lines of aviation—engine building, plane construction and transportation itself.

Capitalized at $150,000,000, the actual assets of all companies concerned cannot exceed $5,000,000. Thus the water in the stock is at least 3,000% of actual value–a liberal gift of the financiers to themselves. Thirty blades of profit-producing grass are to grow, where but one grew before! The extra $145,000,000 to be realized from the sale of the stock to the gullible and hopeful investing public will be pocketed by the promoters.

Other mergers fellow these general lines, only the names and amounts are different. On United Aircraft’s board are representatives of General Motors, Ford, Standard Oil and National City Bank, a perfect set-up of the powerful forces which govern America financially, industrially and politically.

There is little need of underestimating the foes unionism must match if it tackles unionization of the air. United Aircraft and Transport will not be an easy nut to crack. Already the industry is interweaving its interests with those of the industrial corporations which have fought unionism to a standstill in other fields. This is a list of some of the powerful corporations directly interested in aviation, through supplying parts, fuel or service:

A.C. Spark Plug, Aluminum (and Andy Mellon), American Telephone & Telegraph, DuPont, Eastman Kodak, Elgin Watch, General Electric, Radio Corporation, Roebling’s Sons, Travelers Insurance, U.S. Steel, Westinghouse, Winchester and all the big oil companies, including particularly Gulf, Standard and Sinclair,

If trade unionism were powerful generally, it might be remarked, an important branch of the air industry could be organized immediately through political pressure on Congress. Appropriations for army and navy planes—still the biggest part of American production—could carry a stipulation that the planes be made under certain minimum wage and working conditions.

Nothing Too Good.

That union conditions could easily be granted is not open to dispute. When United Aircraft promoters proceed to pocket a cool $145,000,000 on a $150,000,000 deal, certainly there is room for decent wages, hours and conditions. Indeed an Aircraft Workers’ Union could in all fairness to prevailing capitalistic standards demand a 30-hour week, a minimum $2 an hour scale for skilled mechanics and $1 for the least skilled, and the most liberal health, sickness, accident, old age and unemployment insurance, to be paid for by the employers. The well-organized building trades have shown the way. Nothing should be too good for the men and women who turn out a product which must be 100% perfect, if it is not to go to pieces in the sky, hurtling occupants to certain death.

Practically, unions could insist on the 40-hour week, a wage scale in advance of the railroad industry and conditions comparable to those in government service and still be considered modest in their demands.

A practical airplane builder, with nearly 20 years experience in the machine shop and the union, sketches aviation organization in these terms:

1. The Machinists’ Union, as the one primarily concerned with engine and plane construction, to study the industry, plan strategy and assign a corps of organizers concentrating on the industry. The appeal to be made to the workers primarily—and only secondarily to the employers.

2. A national airplane workers paper, discussing trends in the industry, outlining organization methods, enheartening rank and file organizers, printing shop news from every factory. “The paper must be an organizer itself,” says this experienced worker-organizer.

3. An intensive campaign of workers’ education—progressive, militant and intelligent—among new members, training them in unionism’s practice and ideals so that when strikes come, they can fight courageously with an invincible morale. If the union is merely a business concern, job consciousness will divide the workers, men in one plant will ignore the struggles in other plants, the union will not be the welded unit that the airplane is.

Others may prefer an independent, industrial union, as new as the industry itself and constructed especially to meet the needs of its workers. Whether it were better for an existing craft union whose jurisdiction, however, includes the key workers and perhaps the majority of all workers in aviation or such a new union to undertake the job is of course a debatable question which will be answered by the superior aggressiveness of one or the other on the job. An important factor in favor of the Machinists’ Union, it may be mentioned, is its unquestioned position in the repair field. A local machinists’ lodge has already been organized in Florida for the repair and upkeep of planes, paralleling the scores of auto mechanics lodges which represent the older unionism’s only success in organizing in the auto field.

It requires no flight of the imagination to see ever the better paid workers possessing air flivvers 25 years from now. Plane production then will be measured in the hundreds of thousands annually, instead of in thousands. An army of 5,000,000 to 10,000,000 workers, clerks, speculators, aviators, financiers, technicians, employers will make their living out of the air. America, now air-conscious will in reality sprout wings and soar aloft in business, pleasure, ocean travel.

Will the America that takes to wings, use union made wings, union-serviced wings? Organized labor must answer “Yes, they will be union, 100%.”

Labor Age was a left-labor monthly magazine with origins in Socialist Review, journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Published by the Labor Publication Society from 1921-1933 aligned with the League for Industrial Democracy of left-wing trade unionists across industries. During 1929-33 the magazine was affiliated with the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) led by A. J. Muste. James Maurer, Harry W. Laidler, and Louis Budenz were also writers. The orientation of the magazine was industrial unionism, planning, nationalization, and was illustrated with photos and cartoons. With its stress on worker education, social unionism and rank and file activism, it is one of the essential journals of the radical US labor socialist movement of its time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborage/v28n02-Feb-1929-Labor%20Age.pdf