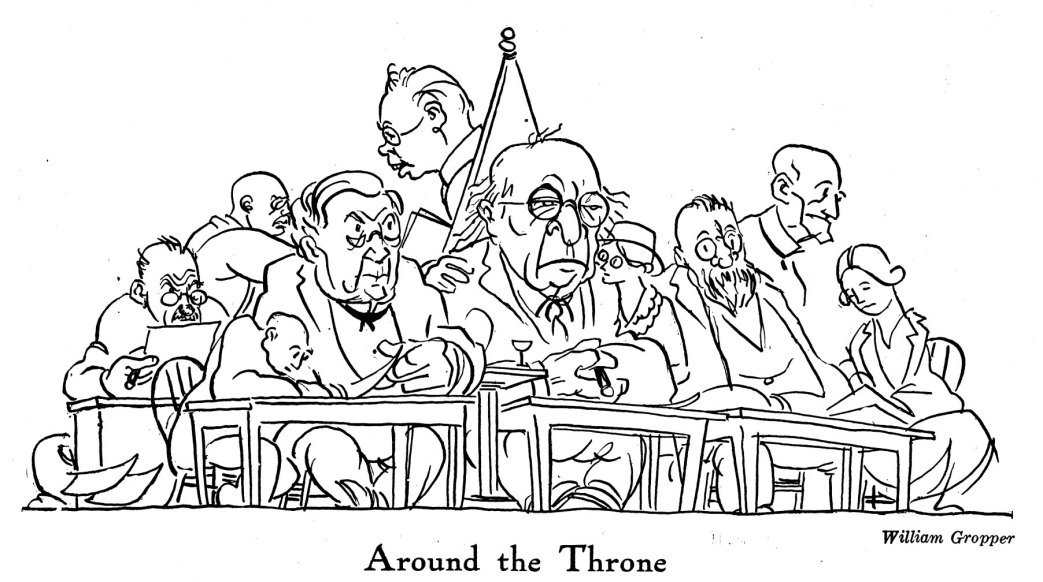

John Reed gives a masters’ class in radical reporting as he travels to Atlantic City in the revolutionary year of 1919 to attend the American Federation of Labor convention presided over by an aging Samuel Gompers. If you want to know why we “can’t have nice things'” in the United States, in part the answer is here. A venal, reactionary labor movement that sees U.S. workers’ interests as tied completely to U.S. imperialism. Illustrated by William Gropper. You can smell the hair grease and cigars. A classic.

‘The Convention of the Dead’ by John Reed from The Liberator. Vol. 2 No. 8. August, 1919.

“We also hear the word ‘reconstruction,’ but there is nothing to be reconstructed in our country.”–President Arthur Quinn of the New Jersey Federation of Labor, at Atlantic City.

FORTUNATE the labor leaders of a city in which an A.F. of L. convention is held! A little committee of “prominent” union officials making the rounds of the hotels, the saloons, the banks…

“The A.F. of L. is going to meet here. Six hundred delegates, with their wives and families-lots of money-free spenders-advertise the city. Besides, you know we’re opposed to Bolshevism…A little contribution to ‘entertain’ the delegates? No publicity, you know…”

Atlantic City was more ambitious. The Central Labor Union sent out circulars to manufacturers and business men all over the country appealing for funds. The letter ran:

“The convention will mark the most momentous period in the history of the relationship between capital and labor, which have been drawn infinitely closer together through the forceful action of Samuel Gompers and the executive council of the American Federation of Labor in stamping out Bolshevik and other radical movements in America and the leading countries of Europe, demonstrating clearly, that the organized labor movement of America will not countenance the disruption of business and financial enterprises created through individual initiative…”

Thousands upon thousands of dollars came pouring in–showing how interested was Big Business in ‘entertaining’ the A.F. of L. Convention. But it was a little too raw; so the Executive Council revoked the charter of the Central Labor Union and returned the money…

There were other similar schemes exposed. For example, at the Labor Press Conference preceding the convention mention was made of the National Labor Press Association, an ingenious plan by an individual named Taite to extort advertisements and cash contributions from banks and manufacturers on the guarantee that the labor papers would combat Bolshevism…

“The working class and the employing class have nothing in common,” says the I.W.W. preamble. This is wrong. They have the A.F. of L. in common. Business men from all over the country, agents of chambers of commerce and manufacturers’ associations, Mr. Easly, of the Civic Federation–all these were in attendance at the thirty-ninth Convention of the American Federation of Labor at Atlantic City. The Mayor, a local real estate shark, welcomed the gathering, saying, “We want here no convention that doesn’t contain men and women one hundred per cent American citizens.” After the great democratic experience of the war, he opined that “the questions between capital and labor will be more easily settled without strike and without turmoil.” President Wilson sent a “May-I-not”; Governor Runyon, of the labor-hating State of New Jersey, called Sammy Gompers “one of the great men of God’s world to-day;” Secretary of Labor Wilson, red-handed from expelling “alien agitators” from the land of the free, denounced the proposed Mooney strike, which he said would undermine the noblest heritage of democracy, the jury system, and attacked Bolshevism, which, according to him, meant only ‘obligatory labor.’ Dealing with the I.W.W., he said their central doctrine was “that every man is entitled to the full social value of what his labor produces.

“This is sound,” he went on. “The great difficulty has been that human intelligence has not yet devised a method by which we can compute what the social value of anyone’s labor is…”

No place could be more appropriate for an A. F. of L. convention than Atlantic City–a pleasure resort, without industry; a place where the delegates would not be embarrassed by the presence of the toiling masses–where no strike could occur to mar the harmony of the proceedings. The convention would be safe in the Coney Island of the Rich!

Along the sea-front the lofty fantastic facades of the great play–hotels, the peanut and popcorn stands, candy counters, shooting galleries (bearing the legend, “Two patriotic duties–Buy Liberty Bonds and Learn to Shoot”), the bathing-houses and amusement piers, blatant with merry-go-round music and the shrieks of pleasure-seekers bumping the bumps–interspersed with extravagant jewelry shops, fur stores, branches of New York and Paris milliners, modistes, stock. brokers, banks; the wide, surf-pounded beaches crowded with bathers in the bright sun, and overhead the airplanes and “blimps” whirring up and down from the Air Port to the Inlet (at twenty-five dollars a passenger).

On the wide Boardwalk the strutting peacock procession, and the interminable lines of wheel-chairs pushed by negroes, in which recline hard-faced women splendidly arrayed and Tired Business Men.

At night the cabarets on side streets going full blast till morning, jazz bands and the wriggling shimmy, nasal songs of syncopated lamentation over the coming aridity (“You Can’t Do the Shimmy on a Ginger Ale!”); for lonely strangers the institution of the “hostess” a title borrowed from the army camps during the war–girls hired by the management to wear gay clothing and dance and drink with melancholy strangers who have failed to pick up butterflies on the Boardwalk…

Into all these local diversions the representatives of the American industrial proletariat, each with five or six hundred dollars “expense money”–besides his private fortune–entered with zest. The towering and gorgeous hotels housed many; they rode, white flannel trousered, in the wheel-chairs, smoking heavy cigars; at night they crowded the bars, or shimmied in cabarets where highballs cost a dollar apiece, and called all the “hostesses” by name.

One delegate a workman–remarked feelingly, “I wish to God I could bring my membership down here and show ’em what becomes of the surplus value!”

A delegate from a Middle Western city buttonholed Treasurer Tobin, delegate of the Teamsters’ Union.

“I’ve got twenty-five teamsters in my town who want to organize. If you’ll send us an organizer we can get a strong Teamsters’ Local inside of a couple of weeks.”

“How many can you get?”

“About two hundred.”

Tobin made a rapid calculation. “An organizer costs fifteen dollar a day. Two hundred teamsters would bring in a per capita of only a few dollars a month. There’s nothing in it…”

Out at the end of the steel pier rose the white cupolas of the Convention Hall, a great room walled’ with glass, standing above the rolling Atlantic surges. In the entrance, two objects: one a huge symbolic bronze panel, “The Triumph of Labor,” presented by the British Trades Union Congress Parliamentary Committee; the other, a cabinet full of samples of paper manufactured by a private corporation, which has water-marked its product with the union label. This advertising scheme is in charge of a member of the Paper Makers Union, whose international president himself hands around circulars advising all union men to buy this paper because it bears the union label! Within, at long tables, some six hundred delegates, and on the platform, flanked by clusters of Allied flags. a row of wooden tables and a speakers’ stand. To the left sit the secretaries and stenographers; to the right, the fraternal delegates from England, Canada Japan; in the rear, the Mexican fraternal delegate; and in the center, in a tall, carved, grand-ducal chair, Samuel Gompers himself, the most grotesque figure that ever presided at any human gathering. Squat, with the face of a conceited bullfrog, the sparse gray hair hanging from his bald head in wisps, as if it were glued on; speaking with a mincing, “refined” accent. He was considerably older than when I last saw him, and at times his mind appeared to slip a little; but his control of the convention was as autocratic as ever, and he ordered delegates to their seats, shut off debate, squelched rebellion with his customary ease–and perhaps even more easily, for there was less rebellion than ever.

One delegate, whose union had suspended for refusing to abide by the ruling of the A.F. of L. in a jurisdictional dispute, hurled at him: “My union is destroyed. But I want to ask the chair, isn’t it the rule that no charter can be revoked without a two-thirds vote of this body?”

Gompers summoned to his side old Jim Duncan, the first vice-president, with whom he held a low-voiced conversation, looking at his watch, while the delegate stood waiting for an answer.

After a few minutes the Old Man arose and pounded the stand with his gavel. “The hour of adjournment having arrived,” he said with a smile, “I declare the convention adjourned!”

By Gompers’ side sat a slight little woman in black, who occasionally fed him a glass of wine. This was the only visible evidence of his recent accident; there was very little talk of that, however–for it appeared that Mr. Gompers had been riding in a “scab” taxicab when he was injured.

About him stood his chief lieutenants, the floor leaders of the Machine: old Jim Duncan of the Granite Cutters, member of the Root Mission, to Russia said to be the world’s long-distance whiskey-swiller–a white-mustached, lean old Scotchman, dour and unloved; John P. Frey, of the Molders, a plausible, well-dressed, youngish man who looked like a stock-broker, and Matt Woll, of the Photo Engravers, a smooth young man who was being groomed for vice-president.

Most of the old-time radicals, cynical from long experience, were not active. The fight against the Machine was led chiefly by James Duncan, of Seattle, a little red-headed man; “Curly” Grow, of Los Angeles, also red-headed, a machinist with a bull voice and no fear; Deutelbaum, of Detroit, a stocky, intelligent Socialist, whom Gompers persisted in calling “Nudelmann”; J.J. Sullivan, of Salt Lake, a “red” Irishman; C.W. Strickland, of Portland, Oregon, an old-fashioned liberal with a drooping gray mustache, who introduced scores of radical resolutions and defended the radical side of every question in a mild, calm voice, utterly disregarding the attempt of the Machine to make him the butt of the convention. And among others, Brown and Schoenberg, of the machinists; Bollenbacher, of Pennsylvania; Sweeney, of Philadelphia; J. Mahlon Barnes, of the cigarmakers, and the foreign-born delegates of the needle trades.

Externally there was little to differentiate the assembly from the annual convention of the National Association of Car Manufacturers, which was meeting at the same time in another hall. Almost all the delegates wore emblems of fraternal orders–Elks, Masons, Knights of Pythias–which, as everyone knows, are merely commercial clubs for business men. More than a third of the delegates were themselves employers of labor; all but a few were well-to-do. Even the newspapers commented upon the display of diamonds. Sixty-five delegates dominated the Convention, representing about twenty-eight thousand votes. These were all officials of the great national and international unions. They were expensively dressed, and their figures portly. Long absence from their trade had filled out the hollows of their cheeks, leaving heavy jowls, and the strong lines made by hard work coarsened and overlaid with self-indulgent fat.

Sinister suggestions of graft, of murderous violence bought and paid for, of political trading, of strikes betrayed, union treasuries looted, hovered about them. Here was an official of the Building Trades, who could be hired at a regular price by embarrassed contractors to call a strike. And there, an official of a Middle Western coal miners’ union, who was at the same time on the pay-roll of the coal company. Another official, president of an international union with an income of $400,000 a year, had failed to account for $100,000 of the Union’s money; some of the locals joined to investigate, and the president suspended them, and hurried to Atlantic City to get the support of the “machine.” But the rebel leader of the insurgent locals served him with a court summons to answer an injunction, on the boardwalk in front of the Alamac Hotel, to the screaming profanity and threats of the official. Hundreds of these obscure, murderous little dramas of internal union politics were being played, with their connotation of gun-men, of the turning out of lights in union meetings, and shooting.

It was symbolic that this Convention should meet in a hall at the end of a pier stretching out to sea. It held itself aloof, not only from the new currents of thought and action flowing through the outside world, but from the labor movement of America. And every effort seemed to be made by the A.F. of L. officials to keep it so. With this in view the fraternal delegates consisted of a little Japanese politician named Suzuki, who denied the Japanese atrocities in Korea; J M. Walsh, a Gompers lieutenant from Canada, and Luis Morones, General Secretary of the Mexican Federation of Labor, also a creature of Gompers in the formation of the Pan-American Federation of Labor. listen to these men, one would think that the American Federation of Labor was the leading organization of the workers of mankind—and that Trade-Unionism was the perfect weapon for emancipating labor. But the delegates of the British Trades Union Congress, especially Miss Margaret Bondfield of the Independent Labor Party, spoke a different language, which would have been disconcerting had the delegates understood it. Gompers had been boasting that the A.F. of L. represented the most numerous organization of workers in the world; but here was a little woman who represented four and a half million workers–a million more. Gompers had advised against the formation of a separate Labor Party, and condemned Socialism; but Miss Bondfield spoke for a labor movement which had its own Labor Party, the greatest political force in England, and in the near future. certainly heir to the British Government; and this party was planning to resume relations with the Socialist Internationale, and advocated the end of capitalism, and “production for use instead of for profit.” Gompers denounced the strike for political purposes, and disapproved of the general strike; but this girl spoke of the mighty Triple Alliance, and its threat to paralyze England to halt intervention in Russia. Gompers attacked Bolshevism and praised the Peace Treaty; but British Labor had attacked the Peace Treaty–and as for Bolshevism, Miss Bondfield told a story about two dockers she overheard. One said: “I saw in the papers to-day where they call Bob Smillie a Bolshevist and a follower of Lenine.” Said another: “Well, if Lenine is anything like Bob Smillie, he is a damned good sort!” And Miss Bondfield ended: “Oh, the stupidity of trying to fight us by calling us Bolsheviki!” But in the official report of her speech this was stricken out, with all other remarks unpleasing to the Machine.

This was the only opportunity Miss Bondfield got to inform the delegates what was going on in England. During the debate on the Labor Charter to the League of Nations, one delegate, wishing to get before the delegates the information that British Labor was against it, asked that she be allowed to tell the attitude of the Trades Union Congress; but Gompers quickly ruled it out of order.

It was impossible to keep out all information, however. The One Big Union movement in Canada and the West, industrial unionism in its various manifestations, the Seattle strike, the Winnipeg strike, the spread of “Bolshevist” doctrines everywhere—all these beat upon the Convention and surged up within it. They had to be, and were, brought out, denounced and scotched, without debate. Soviet Russia had to be met and destroyed, and the Committee on Resolutions did the job.

The appeal of Wilfrid Humphries to address the Convention about Russia had been met by Frank Morrison’s quiet refusal. “We know all about Russia,” he said. “Jim Duncan was there.” At the same time every opportunity was given to the Kolchak forces to distribute their lying literature in the Convention Hall.

There were a number of resolutions concerning Russia introduced. One had to do with the lifting of the blockade; another, with the withdrawal of American troops from Russia; and the third, offered by Duncan of Seattle, requested the A.F. of L. to take a referendum of organized labor throughout the country on the question of recognizing the Soviet Government. The committee’s recommendation “expressed its conviction that the troops should be withdrawn at the earliest possible moment;” and secondly, refused the endorsement of the Convention to the Soviet Government or any other Government in Russia, until the Russian people, through a Constituent Assembly, should establish a “democratic” form of government.

In explaining the resolution, Secretary John P. Frey said: “The official claim of the Soviet Government is that it represents the workers, and only the workers, and for that reason such a form of Government should not receive the endorsement of the Convention of the American Federation of Labor…We cannot endorse any Government but one based upon universal suffrage of all the people.”

Old Andrew Furuseth uncoiled from his seat. “Should we apply this standard to Belgium?” he asked, and sat down. The Secretary’s embarrassment was covered by President Gompers’ gavel.

Gorenstein, of the Ladies’ Garment Workers, asked if this resolution meant that the Convention approved of sending ammunition to Kolchak with which to murder Russian workers? Gompers replied that he considered the question an insult to the Convention. And so, without a word said concerning the lifting of the blockade, debate being ruthlessly shut off, the recommendation was passed–less sympathetic than the declarations of the Allied Peace Council–less liberal than the statements of the United States Government.

In return for the betrayal of Russia the Machine was obliged to permit the passage of a resolution calling upon the Government to recognize the Irish Republic. This concession to the Sinn Fein politicians secured their consent to all further foreign policies, however reactionary, that Gompers might wish the Convention to adopt. In its subservience to the Wilson administration the Machine tried to prevent the recommendation for absolute recognition; but after all, the Senate had done practically the same thing, and a resolution more or less could do no harm. So Gompers left the chair, and it was passed, at the expense of the European Revolutions–just as the Tchekho-Slovaks sold out Soviet Russia for their own independence.

The Seattle strike was only mentioned once–in the debate upon the anti-Prohibition resolution. Supporting Prohibition, Duncan of Seattle pointed out that since the workers of the Northwest could no longer fuddle themselves with drink, they had begun to use their minds, and to act.

“Well,” replied Gompers, “if what has been going on in Seattle is the result of Prohibition, then we don’t want it!”

The first business before the Convention was consideration of the reports of the A.F. of L. Missions to Europe. From the first cablegrams of Oudegeest and Henderson, sent through the American Ambassador and the State Department in November and December, 1918, proposing the calling of a new International Socialist and Labor Conference, we see Gompers balking and intriguing. He evaded a direct answer; refused to be bound by the Interallied Conference at Leeds; refused to meet with the Socialists, saying: “We regard meetings with representatives of political parties conducive to no good results.” When Henderson, Vandervelde and Thomas called the Trade Union Conference to meet coincidently with the Socialist Conference at Berne, Gompers and the other A.F. of L. delegates refused to attend, but remained in Paris “in close touch with the Peace Commissioners,” and tried to stage their own private Labor Congress. “Our position in the matter (the Berne Conference) was approved by the President and the American Commissioners,” says Gompers, naively.

In London he tried to detach the reactionary British unions from the Labor Party; in Paris he sought to create a backfire against the Berne Conference, and persuaded the Belgian delegation not to attend. Finally Gompers, the only bona fide representative of labor in the world who could be trusted by the imperialist Governments, allowed himself to be appointed a member of the Commission on International Labor Legislation, where his vanity was gratified by being elected president–and where, as he himself testified, he was in “absolute harmony” with the other American delegate, who represented capitalism in the United States, Harry J. Robinson. Thus Gompers served as sponsor for the ridiculous and meaningless Labor Charter attached to the covenant of the League of Nations.

The Labor Mission to Italy, ignored by the official Socialist and Labor movements, consorted with such organizations as the Humanitarian Society—a semi-governmental charity; the Co-operative Unions; and the Catholic Workmen’s Society–a reactionary anti-Socialist organization.

In these Labor Missions the A.F. of L. was used by the Allied imperialists to try to break the solid front of the revolutionary working class of Europe, to play the stool-pigeon and the provocator. Diplomatic representatives of the various governments accompanied them everywhere; they were received by kings and field marshals, banquetted, junketted, taken on trips to the front, where they associated with officers. Everywhere they pretended to represent the entire American working class, carefully concealing the fact that the American Government had refused passports to the Socialists, while it permitted, if it did not finance, foreign tours of the Wallings, the Spargos, the Russells.

The convention displayed every mark of satisfaction at the honors received by the A.F. of L. abroad. The most important point, however, was the debate on the labor charter and the League of Nations. Andrew Furuseth had given notice that he intended to attack the labor charter several days beforehand, and Gompers was worried. It was chiefly for this that he allowed the “recognition of the Irish Republic” resolution to go through. Before the debate he carefully polled the most important delegations and wired to Wilson in Paris.

In private conversation Furuseth characterized the League of Nations thus:

“It’s like the proposal of an old roue to a girl of seventeen; not a young man proposing to a young woman–not a mature man to a mature woman, but an old, debauched man-about-town to an innocent young girl. She thinks his intentions are honorable.”

By far the most interesting figure of the convention was Andy Furuseth, delegate and organizer of the Seamen’s Union; a tall, thin, stooping old man, wearing the flapping trousers of the old-time, sailor, his thin face, with its hawk-like nose and piercing eyes, twisted and wrinkled as if from lifelong torture; always unsmiling, speaking in parables full of a sort of deep, calm cynicism. Once, when they threatened to arrest him in San Francisco, he said: “Well, they can’t make me any lonelier than I have always been; they can’t give me worse food than I’ve always eaten nor worse clothes than I’ve always worn, and they can’t make me suffer more than I’ve always suffered. So let them arrest me.” Always lonely–this is the impression I have of Andy Furuseth, with his philosophic detachment from the people about him, and his deep and quiet despair.

We met him one night on the Boardwalk, and someone spoke of revolution. “The kind of revolution you’re looking for, young man,” said Furuseth, suddenly, “will come after you are long in your grave.” Someone else commented upon the reactionary character of the convention.

“But,” said a young delegate, eagerly, “they’re sitting on a volcano!”

“Volcano, hell!” interrupted Furuseth. “They’re sitting on a mud-bath!”

On Friday morning, June 20, under a special order of business, Furuseth shambled out on the floor and began to speak against the labor charter. There was a sudden silence; everyone, even Gompers, respected the mind of this lonely man.

He began by pointing out that Gompers had striven for forty years to have it written into law that “labor is not a commodity or article of commerce,” and that in the labor charter it said “Labor is not merely a commodity.”

“It’s like,” he said, “someone should want to say, ‘Andy Furuseth is not a scab,’ and, instead, he had said, ‘Andy Furuseth is not merely a scab.”

The American delegates had tried to have written in the labor charter a provision against human slavery, and another providing that sailors who left their ships in a safe port could not be arrested and brought back; but the other commissioners, under the leadership of England, had rejected both. England was setting up at this moment a slave state, Hedjaz, on the Gulf of Persia. But even after the charter had been approved and the American delegates had gone home the diplomats who remained had altered and considerably weakened the charter. Moreover, the charter set up a superlegislature, composed of three delegates from each country–one from labor, the second from the employers and the third appointed by the Government–which had the power to interfere in the internal labor affairs of each country and to alter the private life of every workingman.

Gompers, in reply, quoted a cablegram from President Wilson, which admitted that the labor provisions had been “somewhat weakened”–although he did not say how. Gompers then launched into a bitter personal attack on Furuseth, whom he accused of protesting to President Wilson about the provisions behind the backs of the American delegates. He ended with a patriotic outburst and a eulogy of the President, which was received with a tremendous ovation–surely this convention is the only assembly of human beings on the American continent who would still cheer Woodrow Wilson! And with an amendment to the effect that nothing in the League of Nations should be construed as affecting the sovereignty of Ireland, the league and the labor charter were passed, without further discussion, by a vote of 29,000 to 420.

Said Gompers, in the course of the discussion: “It is not a perfect document and we do not pretend it is perfect. I’ll admit even that the labor charter does not even guarantee the rights which labor in the United States has won for itself. But it is not for ourselves, the most advanced labor movement in the world, that we need this charter; no, it is for the workers of the backward countries of Europe, into whose lives it will bring light and enable them to catch up with us.”

It was in this tone that the chiefs of the Machine always spoke of the A.F. of L.; that it had given American workers shorter hours, better wages, better living conditions than any other labor organization in the world. And the delegates believed these things. But if the Labor Mission had gone to the Berne Trade Union Congress it would have discovered that all over Europe the labor movement had advanced far beyond the A.F. of L.–even in the matter of hours, wages and conditions. In the Central Empires, for example, and in Scandinavia the forty-four-hour week was in full sway; the right to strike and picket was universal, as was the closed shop, the right of election of foremen, etc. In fact, the delegates of the British trades unions found themselves a “backward” country; but the countries whose labor conditions were the worst of all, conditions which embarrassed the elaboration of a progressive labor program, were Japan, India, Egypt and the Southern States of the United States!

At the opening of the convention on Thursday morning, June 19, Luis N. Morones was received as fraternal delegate from Mexico. Two hours later the convention went on record as favoring the exclusion of foreign immigrants–including Mexicans–for at least two years.

I saw Morones outside the Convention Hall. His face was grave with anxiety, and his hands shook.

“Senor Morones,” I said, “the first convention of the Pan-American Federation of Labor will be held in New York City next month. What will be the effect of this exclusion act?”

“Desastrosa!” he burst out–which means, in Spanish, much more than “disastrous.”

“What will be the effect upon the Mexican workers?”

He hesitated for a moment, and then said, in a tragic voice: “Our people know that the imperialists of your country want to annex Mexico. But we thought that American labor would refuse to support these evil designs, and it was for that reason that we welcomed an alliance between the workers of all the American countries. But I fear that this act of the convention will destroy the confidence of our people—will make them believe that American labor will regard with indifference the invasion of my country.”

Upon this resolution the radical delegates made a strong and bitter fight. Duncan of Seattle, Grow of Los Angeles, Strickland of Portland, Ore.; Sweeney of Philadelphia, and the foreign-born workers protested that the resolution denied the right of political asylum to the persecuted of the earth. Sweeney said, “If the American Republic falls, it will be through the concentration of wealth and not through immigration.” He accused the A.F. of L. of being poisoned with capitalistic ideas. Delegate Sumner shouted, “If we had any brains or strength we would get back our heritage in natural resources from those who have taken them away from us, and not be wasting our time discussing immigration!” Duncan of Seattle registered his protest, at the same time admitting “that the Federation Machine is too powerful to combat here.’ He said he was afraid that the convention would be able to defeat “our aims for the international brotherhood of the working class.”

That this was the object of the Machine was proven by the convention’s action upon another matter. Several resolutions had been introduced urging that all contracts with employers should terminate on May 1st, and that Labor Day should be changed from September 1st to May Day, so as to demonstrate the strength of labor on the same day that the great labor movements of the rest of the world celebrated. The committee recommended non-concurrence with the resolution, on the ground that each union must decide for itself the best time to terminate its contracts.

The radicals pointed out that this condition of affairs, in which one union which had not terminated its contract was forced to scab on another which was on strike for a new contract–as had happened in Colorado in 1913—was a direct aid to the capitalists, and that the A.F. of L. had always recommended that unions terminate their contracts on the same day.

John P. Frey, for the committee, let the cat out of the bag. “It is coupled with a date which, regardless how trade unionists may look up it, would be accepted by a great many employers, as well as workers, as being connected with the first of May as observed in Europe. The adoption of the measure would…be unwise.” Then Gompers himself took the floor. “It is not generally known,” he said, “that May 1st as Labor Day was suggested to the workers of Europe by the American trade unionists in 1886. Since then we in the United States have firmly established our Labor Day on September 1st. It has quite a different character to May Day in Europe and should not be confused with it. May Day in Europe is linked up with the annual celebration of a political party (the Socialists), with which we wish nothing to do. Besides, here in America we have made Labor Day a holiday–even a legal holiday–while in Europe the workers do not dare celebrate May fist as a holiday, but must go to work as usual on that day and only hold their celebration in the evening or on Sunday…”

Secretary Frey ended with the sage remark: “It would be very dangerous and unwise to celebrate Labor Day at the time our contracts with our employers terminate. At such periods heads are hot and everybody is excited. For that reason it is better to have Labor Day in September, at a time when very few contracts terminate, and labor is not excited, but cool and collected. The calmness of labor makes its demonstration more impressive…” And with this the proposition was voted down.

On the question of the labor party, the Executive Council had advised strongly against any separate workers’ political organization. In view of the strong sentiment in the ranks of the great unions in favor of such a party, however, Matt Woll announced for the Committee on Executive Council’s Report that the A.F. of L., while still opposed, did not think it proper to interfere in the internal affairs of the affiliated unions…

At the beginning of the convention Mrs. Rena Mooney had been granted the floor to address the delegates. Later on, the Mooney affair came before. the body in a series of resolutions, many of them urging a general strike.

The Committee on Resolutions reported an emasculated motion requesting the Executive Council to “take steps” to secure Mooney a new trial. Then it proceeded to condemn the idea of a general strike; and in order to cover up the inactivity of the A.F. of L. concerning Mooney during the last three years, and the treachery of those labor leaders who have sabotaged his case, the committee delivered a furious attack upon the International Workers’ Defence League, which it accused of having misused funds contributed by union men and having by union men and having conspired to break down the American Federation of Labor.

The passionate speech of Patterson, for the league, who cried out that without the league union labor would never have heard of Mooney–which is true; the hot-headed remark of Duncan of Seattle, apropos of the accusation of misusing funds, “We’ve seen a good many drunken organizers of the A.F. of L. out our way!” followed by Gompers’ challenge to name them, which Duncan declined to do; the speeches of many delegates, and the attempts of others who sympathized to get the floor–all these availed nothing.

As usual, debate was rudely shut off and the committee’s recommendation adopted, virtually condemning Tom Mooney to life imprisonment.

Followed the resolution not to demand freedom for political prisoners, accompanied by the committee’s gratuitous remark that “many of the sentences were fully warranted,” and jammed home by a spread-eagle speech from Weaver, of the musicians, who spoke of “traitors at home,” and “the dead in Flanders fields”–and all that remained to do, in order to complete the reactionary record, was to refuse to ask for the repeal of the Espionage Act. This was done–or, rather, the repeal of the Espionage Act was demanded “after the signature of peace,” when it will be automatically repealed, anyway.

Thus while the labor movements of the whole world are demanding at least a fuller measure of democracy in industry; while they declare themselves at least against intervention in Russia–as I write, the labor movements of France, Italy and England are preparing for a general strike on July 20th against intervention; while they strike to free their own leaders, and among them Tom Mooney and the convicted I.W.W.’s, and in no uncertain terms insist upon an amnesty for political prisoners; while they develop shop steward committees, shop committees, labor parties; while with gathering momentum they move toward the brink of the Social Revolution–the American Federation of Labor goes backward, hopelessly entangled in the mazes of its narrow craft unionism, corrupt and ignorant.

The usual attempts were made by delegates to democratize the machinery of the A.F. of F.–notably the customary resolution in favor of the initiative and referendum within the Federation.

This was opposed by John P. Frey and the committee on the ground that it would permit some outside organizations to “get hold” of the membership and wreck the Federation. “There is such a thing,” he said, “as democracy run wild!”

I spoke to him afterwards:

“You said on the platform a little while ago that you were afraid that some outside organization would get hold of your membership. In other words, the masses of the people cannot be trusted to govern themselves without some higher agency to direct them…” “That is true,” said he…

It will be objected to this account that I have left out two “progressive” steps taken by the convention: one, the resolution violently denouncing judicial interpretation of the law, and calling upon the workers to defy injunctions in labor disputes; the other, the decision to organize the steel workers, and to defy the authorities of the Pittsburgh district who have forbidden the workers to hold meetings.

There is a reason for these two “revolutionary” measures. The A.F. of L. is a trust–the job-trust–aiming to monopolize a commodity–labor. Its fight is not against capitalism as such, but against the free competition of labor. The great employers, in fighting the right of labor to organize (in the A.F. of L., mind you–for Gompers is as bitterly opposed to any organization of the workers outside the A.F. of L. as he is to the open shop), are attempting to break down the A.F. of L. labor monopoly. It is an attack upon property–just as the I.W.W. is an attack upon property from the other direction. And the A.F. of L. fights back, as capitalism fights revolution, without scruple and without mercy.

Do the courts issue injunctions against picketing–against strikes, boycotts? Then, says the A.F. of L. Convention, to hell with the courts. Does the great United States Steel Corporation forbid the organization of its hundreds of thousands of workers? The A.F. of L. will mass its power against the United States Steel Corporation. The mayors and police of the steel towns have forbidden meetings, jailed speakers, run organizers out of town. This is a challenge to Organized Labor, and they will take it up.

In the Alamac Hotel one night I attended a meeting of the Committee to Organize the Steel Industry. At the head of that committee was appointed John Fitzpatrick of Chicago, who will recognize the Revolution when he sees it coming down the street, and William Foster, old-time wobbly and syndicalist at heart. When there is desperate business of this kind afoot it is the radicals who are picked to do it; afterward–

Old Andy Furuseth made a motion that the presidents of the great international unions pledge themselves to go into the Pittsburgh district one by one and lead the fight for free speech and the right to organize, risking arrest and violence of the Steel Trust gunmen. There was a certain hesitation among the officials present…

“It doesn’t do any harm to your reputation to get arrested,” said Curly Grow. “Why, I’ve been arrested five times out on the Coast and my prestige hasn’t suffered…”

Under the urge of the general enthusiasm twenty-four international presidents who were there pledged themselves to go.

As we came away from the meeting one of the boys spoke to Andy Furuseth. “Well, the boys didn’t seem very much exalted over their coming martyrdom,” he said.

Furuseth turned to him with solemnity. “Young man,” he said, “do you know why the Catholic cardinals wear red?” “No.”

“In token that they shall be the first to shed their blood in defense of the Church.”

The Liberator was published monthly from 1918, first established by Max Eastman and his sister Crystal Eastman continuing The Masses, was shut down by the US Government during World War One. Like The Masses, The Liberator contained some of the best radical journalism of its, or any, day. It combined political coverage with the arts, culture, and a commitment to revolutionary politics. Increasingly, The Liberator oriented to the Communist movement and by late 1922 was a de facto publication of the Party. In 1924, The Liberator merged with Labor Herald and Soviet Russia Pictorial into Workers Monthly. An essential magazine of the US left.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1919/08/v2n08-w18-aug-1919-liberator-hr.pdf