Edith Margo on the World War One-era development of Chicago’s Black working class South Side and Communist organizing there in the early 1930s.

‘Chicago’s South Side Sees Red’ by Edith Margo from The Daily Worker. Vol. 10 Nos. 133 & 134. June 3 & 5, 1933.

(From “Left Front,” organ of Chicago John Reed Club.)

IN the open space among the trees thousands of people are gathered. Around them the park is dark and cool, but here flood lights bleach the brown and black faces to a greenish white, while the close packed bodies swelter in the heat.

On the ground, facing the platform, hundreds of men and women sit on coats and newspapers. Around them a wide circle of benches is occupied by plump matrons and strangely quiet children, while behind the benches men stand ten deep. They are plainly dressed, serious, hard working people. Some of the men wear overalls, while others are actually in rags. Over at the white Bug Club in the south end of the park speakers are haranguing about religion, tariffs and patriotism. But here, at the Negro Forum in the northwest comer of Washington Park, in the summer of 1932, speakers are concerned with the present—and the future.

A Negro Speaks

A black man is talking. He says he is sixty-eight years old. He tells the crowd that they have listened too long to preachers. They applaud, looking at each other somewhat sheepishly, chuckling over their old stupidities: “Tha’s ri-ight, tha’s ri-ight!” The speaker explains how they are worse off today than when they were slaves because the master who had paid five hundred dollars for a “n***r” could not afford to let him starve, while the masters of today, having no investment in human flesh, are not interested in their condition.

“We gotta start things going’ ourselves,” he shouts. “A revolution is what we need. A revolution against white bosses and black bosses!” At the mention of the word “revolution.” there is a murmur among the crowd, a murmur that grows to the hoarse rumble of deep-throated cannon. Then thousands of clenched black fists are thrust upward, in the salute that today speaks its message throughout the world.

***

THE next speaker is a breezy young white man. He has no, hope for the revolution. “It would take a hundred years to organize the American workers.” He patronizingly advises them to wait until the middle class is aroused. He says that their only hope is to help the liberals correct the worst evils of capitalism.

“Hell. NO!” cries a Negro girl on the outskirts of the crowd. Her voice snarls like a whip. The audience is frantic with joy—clapping, yelling, throwing hats in the air, stamping in rhythm. Amid boos and cat-calls the white man retires.

The chairman jumps to his feet and lectures the crowd on their discourtesy to the last speaker. He tells them that they must give a hearing to all points of view. Now other Negro speakers come forward—some with the blurring voice of Alabama, others with the clipped tones of Northern colleges. They talk about charity beans, about evictions, about families living in damp basements. They tell how the Republicans have misled their race. They expose the muddle-headedness of the Garveyites with their Utopian scheme to take the Negroes back to Africa. They explain why Negroes will not be free until the workers own the factories. One speaker describes the wretched shanties for which workers are forced pay high rent. Another exposes discrimination against Negroes at employment agencies, at charity stations, at theaters, in schools, at bathing beaches. And he points out the way in which the police attempt to crush any protest against this elaborate system of Jim-Crowism.

Protest Scottsboro

A short, stocky Negro takes the platform. In a low, tense voice he calls for a protest against the legal murder of the nine Scottsboro boys on a frame-up charge of rape. He explains how their lives can only be saved by a mass protest of workers, because the Alabama courts and the white bosses who control them want these Negro boys to die as an “example” to the Negro masses of the South. A strapping young man in overalls and a tom shirt proposes the motion of protest. Shouts and cheers from all parts of the wide circle record me unanimous endorsement by the audience.

On the fringe of the crowd little groups congregate. A Negro electrician shows his union card to a small group. He tells how the white boss of the A F. of L. won’t let him work even when he finds a job. A young Negro says, “I’m getting tired waitin’. “We gotta start sumpin’ soon.”

***

TO understand the growth and development of the Washington Park Forum, one must know something of the events which have taken place on Chicago’s South Side during preceding years, and of the conditions which caused these events.

Twenty years ago the Negro population lived on Wabash Avenue, State Street, and a few streets to the west from 18th to 43rd Street. Outside of these four or five streets, most of the South Side was occupied by fairly prosperous middle-class whites, with some wealthy families still living on Michigan Avenue and Grand Boulevard, and a large colony of wealthy Jews on these boulevards and around Washington Park. At that time most Negro men worked as Pullman porters, waiters, barbers, and servants, while the women cooked, washed, and tended babies for the white bourgeoisie.

The War Comes

Then came the war with an almost complete cessation of immigrants worn Central and Southern Europe. The stockyards, the Harvester works, the steel mills, had depended on newly arrived European labor to replace their workers who were constantly leaving these dirty, hazardous industries for less strenuous jobs. The labor shortage became so acute that the bosses, for the first time, were faced with paying a living wage, and the workers, organizing unions and striking for shorter hours, safety devices and larger pay.

The late Ogden Armour distinguished himself by solving the dilemma of the manufacturers. He sent his agents into the South to tell the Negro cotton hands of the good jobs which awaited them in Chicago. Thousands and thousands of Negroes trekked northward into the promised land. The Southern plantation owners, alarmed at the escape of their slaves, tried to restrain their workers by force. The night riders rode again. Negroes who had announced their plans to leave were lynched. Sheriffs arrested share croppers who were boarding trains, on the claim of debts owed. But still the migration continued, until Chicago’s Negro population numbered between two and three hundred thousand people.

II.

NUATURALLY the old black ghetto was not large enough for this immense new population. Real estate dealers, both white and Negro, reaped a harvest by turning white neighborhoods into black. A house or apartment building in a white block would be bought and rented to Negroes. Then the white bourgeoisie would be frantic to sell their properties at a fraction of their former worth. The real estate dealers would make a substantial commission on the sale, and would earn a handsome profit by renting the property to Negroes at rents far in excess of what the whites had paid. Gradually the Negroes spread out over most of the South Side, occupying an area of about ten blocks to the east of their former district and from 18th to 61st Street.

“Winning the Negros”

The white politicians were quick to make use of this great Negro mass. Previously, Chicago had always voted Democrat. Now the Bill Thompson faction in the Republican Party saw a chance to build up a machine based on the Negroes, most of whom had never voted before, and who believed that the Republican Party was the friend of the Negro because their white bosses in the South had been Democrats. Thompson therefore set out to court the Negroes. He appeared at their dances, their parades, their bazaars, and mass meetings. He appointed Negroes to public jobs, of course in minor positions (except A.J. Carey, Bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, who was appointed Commissioner of Civil Service, indicted in 1929 for selling jobs, and conveniently died in 1930.) And he formed an alliance with the Negro misleader, Oscar De Priest, and others of the same stripe. From 1916 to 1930, this crew dominated the South Side, working hand in glove with Binga the banker, Abbott the editor of the Chicago Defender, and the Baptist and Methodist ministers.

As most of the Negroes were tremendously devout, they supported scores of churches housed in old synagogues and buildings discarded by white protestant congregations. Some of their churches boasted the largest protestant congregations and Sunday Schools in the world.

***

THE Negro population of Chicago has taken on an entirely different character, much more industrial than New York, for example.

In the spring of 1930, groups of Negroes began to congregate on Sunday afternoons and weekday evenings in Washington Park to discuss their problems. For many years a group of White “radicals,” petty politicians, exponents of queer religions and unclassified nuts had maintained an open air forum in Washington Park, known as the “Bug Club.” During the war the police, activated by the South Park Board, had endeavored to close this forum because of alleged unpatriotic utterances, but Judge Harry Fisher had granted a permanent injunction against the Park Board, restraining them from interfering with free speech at the Bug Club.

By 1930, the Negro population had occupied the houses and apartment buildings on three sides of Washington Park and had taken over the tennis courts, ball fields and recreation houses in the park. Because many of the Negroes had already spent one winter of unemployment, they began to congregate in the park in the spring to listen to the varied solutions of their problems offered by the Negro and white speakers.

Three Groups

Soon the Negroes had formed into three groups, separate from the White Bug Club. One of these was controlled by the Economic Federation, a group of petty bourgeois Negro intellectuals, lawyers and school teachers, who had a scheme for workers to invest a penny a day and become rich in ten years. The money was to be invested in stocks of corporations such as U.S. Steel, American Telephone and Telegraph, and Commonwealth Edison. Another group was called the Good Fellows Club, and was composed of Negro workers and radicals, none of whom had a program. The third group was known as the Ministers’ Forum, and was occupied in discussing the finer points of Genesis and Revelations.

***

A SMALL group of Negro Communists began speaking at the Good Fellows Club in the early spring of 1930. At this time there was still some antagonism against Communists among the Negroes, and these few speakers found difficulty in showing the workers the correct line of action. But they persevered throughout the summer and gradually began to take listeners away from the other forums and to attract the workers who were flocking to the park in ever greater numbers. At that time evictions were taking place in the black belt at the rate of about three bundled and fifty every day. The Communists told the Negro workers that they should organize and put back evicted furniture.

The Eviction Battles

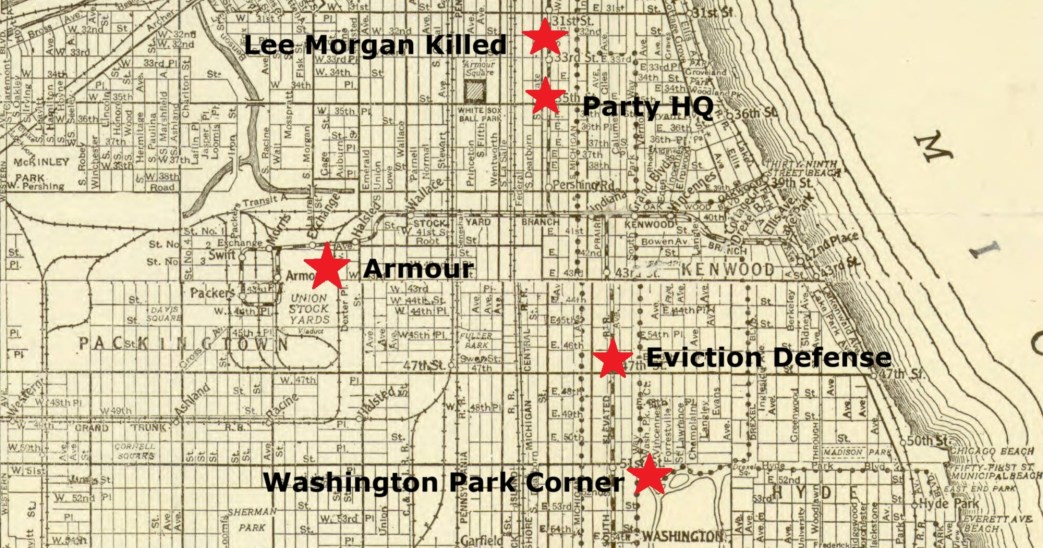

The first furniture replaced was at 4616 Calumet Avenue in the summer of 1930. About twenty people took part in the moving. The police, establishing a custom which has been followed ever since, arrested Poindexter as the leader. In two weeks the family was evicted again and this time the incident took on a mass character. The Communists went from house to house notifying neighbors of the eviction, and a crowd of three hundred and fifty people gathered. Charles Banks and Poindexter were arrested before the furniture was put back, but Gene Sullivan and Lambert, a white comrade, carried on speaking to the workers. After the furniture had been replaced, both Sullivan and Lambert were arrested. Banks and Poindexter were fined one dollar and costs, while Sullivan was fined $75 and costs and Lambert $150 and costs. All of these comrades served their sentences in the Bridewell.

In July, 1930, occurred the first murder in the class struggle. Lee Mason, formerly a Negro Communist candidate for Congress, was slugged by the police during a demonstration at 32nd Street and State Street. His funeral, held from the Party headquarters at 3335 South State Street, was an impressive funeral. Three thousand workers participated in the parade to the 47th Street railroad station.

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1933/v010-n133-NY-jun-03-1933-DW-LOC.pdf

PDF of issue 2: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1933/v010-n134-NY-jun-05-1933-DW-LOC.pdf