One of a handful of daily Socialist newspapers in the history of the U.S. the Chicago Socialist was among the most important publications of the Debs era. The final editor, J. Louis Engdahl, would join the Communist movement in 1921 and become editor of the Daily Worker. Here Engdahl looks at the history of the Chicago Socialist as he looks forward tot he Daily Worker.

‘Romance In Journalism’ by J. Louis Engdahl from The Liberator. Vol. 6 No. 10. October, 1923.

IT WAS late. Night life was beginning to droop in Chicago’s Loop district. But energy developed at an increasing tempo in the composing room of The Daily World, on Washington Street, down towards the river. A half dozen rheumatic linotypes, complaining in every joint, after helping to get out the several editions of The Evening World during the previous day, were now being coaxed by nervous operators to duplicate the feat for the morning issue. For the Chicago Daily World and The Evening World were labor’s twin battery during the historic newspaper strike of 1912.

I was closing up the first page which, under the signature of Charles Edward Russell, emblazoned the latest developments at the National Convention of the Republican Party where Theodore Roosevelt and his forces were frantically fighting for power.

These were tense moments, and hot, on this summer’s night. Even little things were irritating. A turmoil in the front business office, and then a slight human form, with some ragged clothing upon it, came speeding through this scene of activity among the type cases, make-up tables, proof reader’s desks, machines and what not. In the same moment the strange little figure was gone, out through a window and over the roofs beyond. Bellowing police, in plain clothes, followed hotly. But the diminutive newsie would make good his getaway, said the older one. Raids were being made that night wherever newsies gathered, to enforce the truancy law against the younger ones. It was a strike-breaking weapon. This was the first time Chicago’s city administration had ever troubled itself about the newsboys who sold papers on the streets during their waking hours and slept in the alleys at night.

The newsboys were holding their own in this strike of the printers, stereotypers, pressmen, mailers and newsies against Chicago’s Newspaper Trust. The big dailies were helpless with no one to sell them except a few traitors and hired scabs. Even on the Fourth of July, of this memorable year, when the newsies could have made rich pickings selling extras of the Trust press giving results of the all- absorbing fight between the lightweights, “Battling” Nelson and Ad Wolgast, they stood loyal. They jammed the street and waited patiently outside the building that housed the daily paper that was the heart of the fight against The Tribune, self-styled “The World’s Greatest Newspaper,” the Hearst sheets, and all the rest. They were real soldiers of the labor war.

These young workers constituted the strongest link in the chain that was strangling the Trust press into submission. The weakest link was the Socialist Party, the local organization of which owned and controlled the Chicago Daily Socialist, that had been expanded in a night from a crippled, four-page, one-edition sheet with hardly a dozen thousand circulation, into both morning and afternoon publications, each with several editions, totaling a circulation that climbed up towards the half million mark.

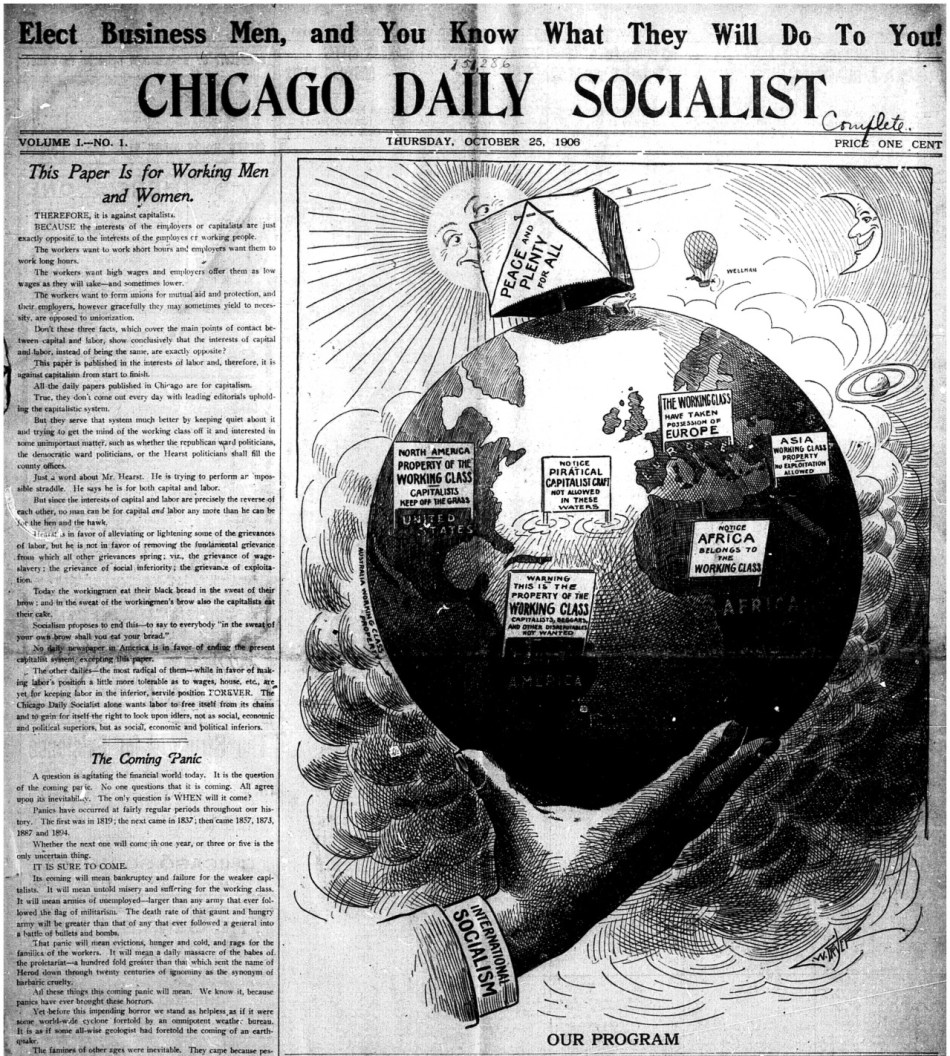

The Chicago Daily Socialist was the first English-language labor daily in the United States. It came to life in 1906 and lived six years. As The Daily World and The Evening World, it died at the moment of its greatest opportunity. The Daily Socialist was established to meet the needs of the Socialist Party. It was choked to death in a local factional struggle.

When Eugene V. Debs, in the presidential elections of 1904, polled nearly half a million votes, the Socialists saw the co-operative commonwealth reddening the horizon. The Chicago Socialists were ready for big things in the 1906 congressional elections. The Daily Socialist was then started as a ten-day pre-election effort. Algernon M. Simons, a settlement worker, had come into the Socialist movement, helped organize the Industrial Workers of the World in 1905, and had written some books, among them “Social Forces in American History.” He became editor. Later, this man was destined to turn traitor, becoming an informer for the Wilson-Palmer department of justice during the World War. His chief associate, in the beginning, was Joseph Medill Patterson, who had suddenly turned revolutionist, deserted the Chicago Tribune in which he had an interest, resigned a high-salaried job in the municipal administration of Chicago’s radical mayor, Edward F. Dunne, and was ready to help overthrow capitalism. The revolution didn’t come; Patterson reverted to his capitalist friends, was 100 per cent patriot during the World War, and is now one of The Tribune editors. The last time I saw him, in Hancock, Mich., in 1913, he was happy with the wine of the copper barons, who were ruthlessly fighting the copper strike of that year.

The 1906 elections passed but The Chicago Daily Socialist continued in existence. It was always facing death through financial starvation. It would brighten up a little during election campaigns. But the 1908 presidential returns fell short of those in 1904, and there was gloom. I came to the Chicago Daily Socialist as labor editor in 1909. Two events I remember clearly. The great excitement in our office and throughout the Socialist Party caused by the election of a Socialist, a real estate gambler, as mayor of Grand Junction, Colorado, was one; and the other event was the protest of Editor Simons that I was getting too much space for my stories covering the activities of the Chicago labor movement. Even to this day those two events typify in my mind the attitude of the Socialist press toward the whole working class. It was only brutal financial necessity that forced the Socialists to allow their daily in Chicago, even as The Call in New York City, to drift into support of the economic struggle of labor.

The Chicago Daily Socialist was endorsed by the Chicago Federation of Labor. Returning from the Copenhagen, Denmark, Congress of the Second Socialist International, in 1910, I became the editor. With no party direction, local or national, the paper inaugurated and carried through its own policy in the 1911 garment strike, out of which grew the present Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America. It was with the same lack of party direction that the paper drifted into the 1912 printers’ strike and thus won its momentary place in the sun. A great opportunity was inevitably turned into a tragedy. Morris Hillquit, the party leader, looked at the lone press that was working a 24-hour shift, and the Socialist Party national executive committee voted a thousand dollars toward a second press. Then Hillquit went back to his law practice in New York City. Victor L. Berger could see nothing but his own daily paper in Milwaukee and his seat in congress. The Chicago Socialists were left alone to fight it out. And they fought–among themselves. The forces led by the two lawyers Seymour Stedman and William E. Rodriguez got the upper hand, at first, only to be deposed by other elements headed by John C. Kennedy. Kennedy started operations by stealing most of the staff of Berger’s Milwaukee Leader, including Chester M. Wright, now anti-Communist propaganda chief for Sam Gompers; Carl Sandburg, the poet; Gordon Nye, the cartoonist, and half a dozen more. In the final combat the sectarians, who were afraid the workers might run away with the paper, won out. Support fell away. The rule of the Street Carmen’s Union, that any member caught reading a capitalistic sheet would be fined $5.00, was forgotten. First the morning issue, The Daily World, was suspended.

Then members of the Socialist Party, themselves, went into the bankruptcy courts. A sheriff’s notice was put on the building and the linotypes and presses were stilled. There was interred in that tomb, for a long time, all hope of reestablishing a workers’ daily press in Chicago.

Other dailies have been brought into existence in other cities since the Chicago Socialist died in December, 1912. There are the Minneapolis Star and the Seattle Union Record, but they have developed into mere efforts to exploit for the advantage of individuals the demand of the workers for a press of their own. The same may be said of Berger’s Milwaukee Leader. Certain trade union officials have joined the old yellow Socialist leaders to re-finance the New York Call. The Oklahoma Leader, born Socialist, died recently when its idol, the democratic Governor Walton turned traitor to the workers and farmers who elected him. The dailies started by the Nonpartisan League in the northwest have also died, because the leaders of the farmers, like Townley, began turning their faces backward.

All this shows conclusively that the rank and file workers and farmers have never had a daily of their own to fight their battles. They have no English-language daily even now, anywhere, to voice their cause. No wonder therefore that labor, everywhere, cheers the coming of The Daily Worker–toilers on the farms of the West, in the factories of the East, and in the mines and mills between.

The hope for a workers’ daily press in Chicago, that was interred in the tomb of The Chicago Daily Socialist, is now being resurrected in the ambitious plans for The Chicago Daily Worker. Where the Socialists failed in Chicago the Communists will succeed. The English-language Communist daily is being called into existence by growing and vital needs of the whole working class. It will be born to struggle. It will live through its consistent and tireless support of all labor against the combined power of all bosses.

The Daily Worker is not intended to be a sectarian preacher of dry formula. It will be the mouthpiece of the broadest efforts of the whole working class. The Call may be Hillquit’s, the Leader belongs to Berger, the Star to Van Lear, the Union Record to Ault. The Daily Worker will belong to the working class. An organ of Communism, The Daily Worker will be the champion, on the political field, of an independent labor party in the United States, of the united political front for the winning of a workers’ and farmers’ government.

The Socialists in the trade unions, J. Mahlon Barnes, in the Cigarmakers’ Union; Dan White, in the Moulders’ Union; Adolph Germer, in the miners’ union, built up groups by correspondence to capture jobs for Socialists. When Socialists were elected they usually deserted the party, like William H. Johnston, of the Machinists’ Union. The Daily Worker, the spokesman for the whole left wing of labor, fighting for amalgamation, for the organization of the unorganized, will fight for principle and not for office. William Z. Foster, Joseph Manley, Jack Johnstone, Earl Browder, Otto Wangerin, William F. Dunne, to mention a few of the great hosts of militants in all industries, will speak through its columns. The Daily Worker will not wait for labor to beg it for help in the economic struggle. It will be in the combat always. Samuel Gompers, John L. Lewis, James M. Lynch use the capitalist press, the New York Times, The Chicago Tribune, and the lesser kept organs to betray labor. The voice of the rank and file will be heard through the Daily Worker.

No fight will be too small to win attention. No struggle will be too great for intelligent handling. The local strike will not be neglected. But every battle will be interpreted in the light of its broader national and international significance.

Berger’s Leader championed cheaper gasoline for a few days and allowed owners of flivvers to delude themselves into the belief that they were winning a lasting victory over the international Standard Oil Company. No one hears of the Star and the Union Record outside of Minneapolis and Seattle. Its infamy alone made the New York Call known beyond its own local environment. Local struggles must be coordinated with the national and international efforts of labor. This The Daily Worker will do.

At the time when The Chicago Daily Socialist died, internationalism was, to Socialists, typified in the Second Socialist International which met every three years, in London, Paris, Stuttgart or Amsterdam. The war hasn’t changed that. The new Socialist International, formed at Hamburg, is still a post office affair. The Daily Worker will breathe the internationalism of the Communist International and the Red International of Labor Unions. Through the contributions of Lenin, Trotzky, Radek, Zinoviev, Zetkin, Newbold, Cachin, and all the rest, it will make the world labor struggle live before the eyes of America’s workers who will thus profit by the victories and defeats of labor in all the nations of the earth.

Who can doubt that the establishment of The Daily Worker marks the opening of a new era in American working class journalism? A half million copies will again be pouring daily from a workers’ press in the city of Chicago, and this will be the most powerful force connecting the far-flung battle lines of the working class of the United States.

The Liberator was published monthly from 1918, first established by Max Eastman and his sister Crystal Eastman continuing The Masses, was shut down by the US Government during World War One. Like The Masses, The Liberator contained some of the best radical journalism of its, or any, day. It combined political coverage with the arts, culture, and a commitment to revolutionary politics. Increasingly, The Liberator oriented to the Communist movement and by late 1922 was a de facto publication of the Party. In 1924, The Liberator merged with Labor Herald and Soviet Russia Pictorial into Workers Monthly. An essential magazine of the US left.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1923/10/v6n10-w66-oct-1923-liberator-hr.pdf