A right-wing Republican candidate, Herbert Hoover, won an overwhelming victory in the 1928 election and a massive majority in the House. Third parties, the Socialists, Communists, and Farmer-Labor, barely registered. In the face of such a situation, Scott Nearing proposed a dramatic retreat corresponding with the retreat of the class. The year following, the Great Depression began and all calculations were necessarily revised.

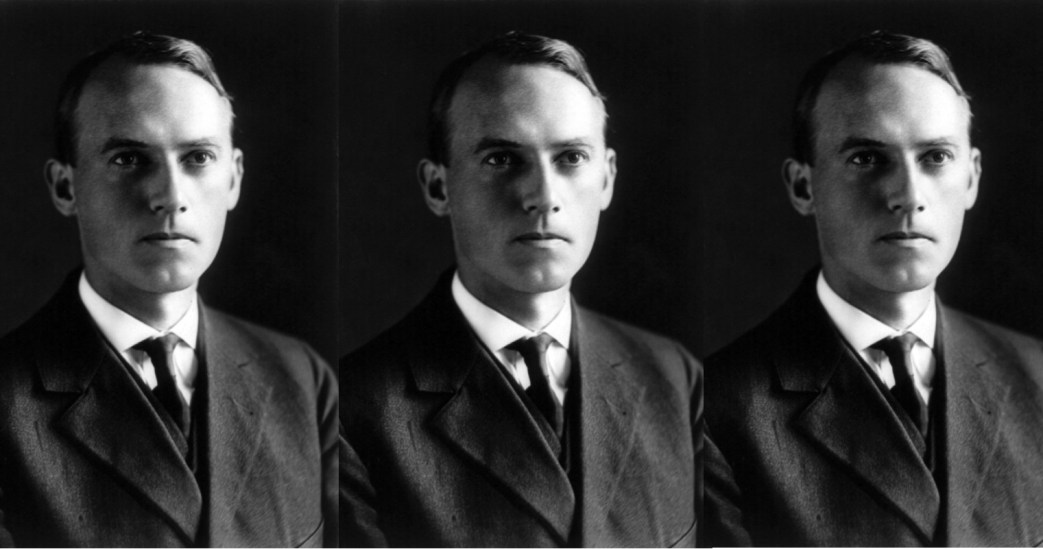

‘Discussion Article: The Political Outlook for the Workers (Communist) Party’ by Scott Nearing from The Communist. Vol. 7 No. 12. December, 1928.

(Note: The article below is printed as discussion material. It is widely at variance with the viewpoint of the Party on a whole series of questions. It was the intention of THE COMMUNIST to publish an answer in this issue, but the answer was not received in time for publication. It will, therefore, appear in the next issue. The Party viewpoint on the election campaign is expressed in this issue by the article of Jay Lovestone, which indirectly constitutes an answer to the article of Nearing. Editor.)

The Workers (Communist) Party made a limited political campaign in 1924, covering fourteen states. In June, 1928, the Party called a National Nominating Convention and launched a political campaign which placed its candidates on the ballot in 34 states. The Party vote in 1924 was about 34,000. The vote in 1928 will probably be more than double that amount, but even at 100,000 the Party would have secured less than one-third of one per cent of the total vote cast in the 1928 election.

The campaign itself was a significant political experience.

Bourgeois resistance to the Workers (Communist) Party constantly increased as the campaign progressed until by October 15th a point had been reached at which the campaign had become a free speech fight in at least half a dozen states. Even where the Party was on the ballot, leading Party representatives were persecuted, driven from town, jailed. The big business interests of Ohio, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, California, etc., were determined that the Party should not bring its message to the working masses.

This stiffened bourgeois resistance showed itself also in the closing of the press and radio to Workers (Communist) Party spokesmen. Republican and democratic candidates were given an unprecedented amount of space. Socialist Party candidates shared in the publicity. Only Workers (Communist) Party representatives were denied those publicity channels through which the American masses can best be reached in a political campaign.

The Workers (Communist) Party was therefore reduced to campaigning through political meetings and through the very limited clientele reached by the Daily Worker and the other party organs. Consequently the Party was unable to attract the attention of the masses. The old parties raised so much noise that the voice of the Workers Party could not be heard above the din.

Outside of New York, in the course of two months campaigning I did not see more than two enthusiastic rallies, and both of them were in smaller industrial towns. The people who came to Party campaign meetings were for the most part apathetic, indifferent, inquisitive, fearful or hostile.

Failure to attract the masses during the election campaign carried with it inevitable failure to increase the party membership. Again with the exception of New York, so far as I was able to ascertain, the two months of campaigning did not bring any considerable increase in party members.

Generalizing: The Party consumed its energy and its means merely in conducting the campaign. It failed to reach the masses and it failed to record any notable membership increase.

The campaign of 1928 seems to have taught three lessons:

1. The American masses are not ideologically prepared for the program of the Workers (Communist) Party;

2. The ruling class in the United States is too well organized, too class conscious, too well equipped with police, sedition laws, etc., to permit effective campaigning by the communists;

3. There is no reason to suppose that the American masses can be reached by Workers (Communist) Party political propaganda in the immediate future. The Party cannot hope to function between 1928 and 1932 as a political mass force.

Still, the political situation in the United States is bristling with important possibilities:

1. The overwhelming defeat of the Democratic Party and its probable elimination as a force in national politics opens the way for an effective opposition party in the United States, including the more progressive elements, and forcing the more conservative elements into the Republican Party; or

2. The American big business interests after their 1928 political victory may establish under Herbert Hoover and his successors the substantial outlines of a fascist state and refuse to permit any further political opposition.

Accepting for the sake of argument the former of these two alternatives and assuming that there is a real possibility of creating from among the mass of dissatisfied farmers, oppressed Negroes, exploited wage earners and dispossessed petit-bourgeois elements, the fabric of a Farmer-Labor Party, is it possible for the Workers (Communist) Party to participate in such a movement and in a degree to determine its ideology and direct its line of activity?

What will be the ideology of such a party? Unless there is a considerable shift in public sentiment its program cannot go much further than the reforms advocated by Governor Smith in the course of the recent political campaign. With such a program it is evidently possible to enthuse the masses. To the left of such a program the masses are not prepared to follow, even in territory like the soft coal regions which have just experienced severe class struggles. No matter who builds this new opposition party, its appeal must be made to the more exploited elements of the United States population.

Will the advantages of such a movement justify it from the communist point of view? Politically, such a movement would be justified even if it did nothing more than to crystallize big business interests definitely in the Republican Party and to place mass farmer-labor interests clearly in opposition to republican big business.

Will the advantages of such a movement justify it from the Communist Party and such a farmer-labor opposition party?

1. The Workers (Communist) Party might hold aloof and denounce the movement. From one point of view it has good reason for such a stand. Experience both here and abroad makes it certain that such a party once organized, will support the basic policies of capitalist imperialism and will oppose communists and communism.

On the other hand, if the masses of workers and farmers can be politically split away and placed in political opposition to republican big business, the first step will have been taken in the direction of class-conscious mass action in the United States. Such a movement will be a valuable rallying point for workers and farmers whose class consciousness is as yet only rudimentary.

2. The Workers (Communist) Party might enter such an opposition openly. But this would involve:

a. The abandonment of revolutionary activities and tactics,—that is, the Workers (Communist) Party would cease to be a Communist Party, or else,

b. The alienation of those mass elements that are not yet prepared, ideologically, to accept the implications of class struggle. In other words, open participation by a revolutionary party is for the moment, politically impossible.

3. If the Workers (Communist) Party cannot afford to let this opposition movement go by default and if it cannot officially participate in its organization and activity, but one possibility remains: The Workers (Communist) Party must send its members into the new organization, without any hope of “controlling” or “capturing” but for the purpose of directing left-wing policy and tactics in the new party. Probably it will be impossible for known communists to take any part in the work of the new opposition party, even as individuals. In that case they must work from cover.

If the Workers (Communist) Party decides to follow this third line of policy the pick and shovel work must begin forthwith.

1. In the municipal campaigns of November, 1929, labor candidates can be run in a number of cities and in farming and industrial districts which seem to offer some opportunity for political success. The localities should be strategically located from the standpoint of class interest in various parts of the United States.

2. Where strength is shown, state candidates can be nominated in the election campaign of 1930. Gubernatorial and Congressional elections will then be held.

3. Again in the off year, 1931, municipal and local campaigns can be waged in territory not already penetrated by the new farmer-labor movement.

4. Granted a reasonable degree of success in the conduct of this program by the Spring of 1932, it should be possible to call a National Convention and nominate a presidential candidate.

Thus far the policy looks simple enough, but:

1. Shall the Workers (Communist) Party having adopted such a policy, run a separate ticket against the new Farmer-Labor Party?

2. If it runs a separate ticket, shall it denounce the new Farmer-Labor Party, or concentrate its attack on the republicans and on the constructive phases of its own program?

3. Will it be possible, by refraining from nominating opposition candidates in certain strategic centers to throw communist support to the new Farmer-Labor Party?

The political campaigns of the years 1928-1932 will be fought, if they are fought at all, between the Republican Party on the one hand, and on the other by an opposition party which may be organized by the farmers and workers. In case this opposition movement does crystallize the protest of the exploited masses, the Workers (Communist) Party may by careful planning, play a role in directing its outlook and drafting its program.

The political energy of the Workers (Communist) Party, during these four years, must not be consumed in the farmer-labor movement, however, but must be devoted to the continuance of revolutionary political organization and agitation along the lines followed in the recent campaign. More local organizers are needed and more local activity is indispensable if the Party is to succeed.

At the same time, there is no reason to indulge in Utopian dreams.

The most that the Workers (Communist) Party can hope for, during the coming four years is steady increase in membership and a broadening of sympathetic support in that small minority of the American farmer-worker masses who are already conscious of the class nature of American society.

There are a number of journals with this name in the history of the movement. This The Communist was the main theoretical journal of the Communist Party from 1927 until 1944. Its origins lie with the folding of The Liberator, Soviet Russia Pictorial, and Labor Herald together into Workers Monthly as the new unified Communist Party’s official cultural and discussion magazine in November, 1924. Workers Monthly became The Communist in March ,1927 and was also published monthly. The Communist contains the most thorough archive of the Communist Party’s positions and thinking during its run. The New Masses became the main cultural vehicle for the CP and the Communist, though it began with with more vibrancy and discussion, became increasingly an organ of Comintern and CP program. Over its run the tagline went from “A Theoretical Magazine for the Discussion of Revolutionary Problems” to “A Magazine of the Theory and Practice of Marxism-Leninism” to “A Marxist Magazine Devoted to Advancement of Democratic Thought and Action.” The aesthetic of the journal also changed dramatically over its years. Editors included Earl Browder, Alex Bittelman, Max Bedacht, and Bertram D. Wolfe.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/communist/v07n12-dec-1928-communist.pdf