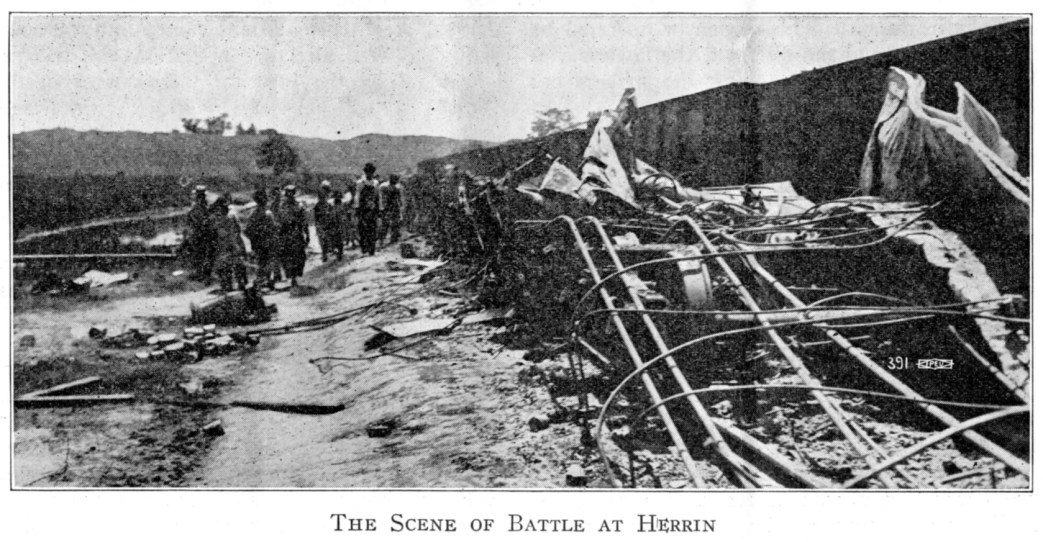

The opening statement by the U.M.W.A. defense attorney in the Herrin murder trials. Given its implications and consequences, the events in the mining community Herrin, Illinois is rarely spoken of, even today. However, Herrin still silently reverberates over the labor, and all liberation movements. Before Herrin, the predominate force facing strikes were hired guards, Pinkertons, and deputized gangs under the direct pay of the bosses. After Herrin, the force we faced was largely the National Guard and the state directly. Why? During 1922’s national U.M.W.A. strike, in disregard to a previous agreement, 50 armed scabs were brought into the mines at Herrin commanded by notorious strike-breaker C.K. McDowell. Those gun thugs killed several strikers shortly after their arrival and were subsequently met with a terror equal to their crimes. Armed miners surrounded the scabs in a fierce gunfight, took their surrender, burned down the mine, and then meted out an enraged justice on the survivors. At least 20 scabs, including McDowell died on June 21, 1922 showing that our side could strike real fear as well as theirs.

‘Herrin Miners Rose in Defense of Their Homes’ from Voice of Labor (Chicago). Vol. 11 No. 580. January 6, 1923.

Opening Statement of Defense Attorney

HERRIN, Ill. W. Kerr, chief counsel for the Illinois Mine Workers, in making his opening statement to the jury in the first of the Herrin trials, said that the defense would prove that the killing of armed guards was the result of the unlawful invasion of Williamson county by these same armed guards and of the many acts of brutality culminating in the ruthless murder of three peaceful unarmed union coal miners.

“We are going to state the facts bluntly, truthfully, as they actually happened.” He described the beginnings of the operation of the Southern Illinois Coal Company, told of the agreement between that company and the United Mine Workers of America whereby the company was allowed to strip but not to mine coal, and touched on the early days of coal mining in Illinois before the union came.

Mining Conditions Pitiful in Old Days.

“No doubt many men in this jury will recall the days when the lot of the actual miner of the coal was a pitiful one indeed. No laws were upon the statute books to protect him, disasters that might well have applied to them the terms of ‘massacres’ were of frequent occurrences in this industry. Human life was snuffed out in the gaseous recesses of the earth to the number of countless thousands. Public officers having failed in their duty, some redress must be had. The single miner, speaking alone, was ineffective–his was a feeble protest. If he were killed, his widow and orphaned children were thrown upon the mercy of an uncharitable world for sustenance. The employer dismissed the death of his miners in practically every instance with a mere expression of regret for the killing. Then, too, working conditions were such that they sent the mine worker to an untimely grave. His vitality was sapped and weakened by the gasses which the greedy employer permitted to exist for want of the expenditure of a few dollars to drive them from the mine. No escapement shafts were provided. No ventilation was thrown into the mine. There was no securing of unsafe roofs. No guarding against other bad conditions. Protest by the individual meant his discharge and perhaps lack of bread and butter for his family. Hours of work sometimes were as long as fourteen and sixteen and eighteen hours out of twenty-four; and wages were so low that the miner was compelled to drag his baby boys from their mothers’ knee into the mine. Before the union came to Williamson county 18 cents a ton was considered high pay. Some of you men remember these things.

Miners Organize for Better Conditions.

“Then the miners organized. At least they sought to organize, and that effort at organization in the state of Illinois presents one of the finest chronicles of the courage of the American worker ever recorded in history. What did these oppressed workers fight for? Why did they seek to organize? To better the condition of their babies, to give them more food and clothing, to give them mental, physical, moral food so that there might be that development of mind and body and conscience which would provide a finer, happier, more intelligent citizenship. And in that battle, at every step these determined workers were met with the powerful forces of organized capital. The miners lost. They lost again and again and again. But they persisted. Private armies of gunmen in the employ of the operators directed their guns against the breast of the workers. The miners went on against all the power of the organized employers of this state until finally they won for themselves an organization. They won their liberty. And now in this case they are assailed for wanting to protect and conserve this organization which has meant so much not only to the state itself, and when I say ‘state’ I mean the people, because after all it is the people that constitute the state.”

Coal Company Broke Contract.

Mr. Kerr said that violating his contract with the union, W.J. Lester, the president of the Southern Illinois Coal Company, proceeded to recruit a private army from among “professional man killers outside the law, with reckless disregard for the taking of human life.” He said Lester had not brought them into Williamson country to protect property which was being invaded or destroyed. “No,” said Mr. Kerr, “Lester brought them in here with machine guns, with high-powered rifles, with automatic police pistols, with all the most destructive are arms known to modern science. None of Lester’s property rights was assailed. There was a Sabbath like calm from one end of Williamson county to another. With an equipment of men and guns Lester established an army headquarters from which base he could invade and terrorize the community to the extent of murder. Among the gunmen we find the deceased Howard Hoffman, now said to this jury to have been in the ‘Peace of the People’ when he was killed.”

Gunmen Inflict Violence.

Mr. Kerr then narrated sixteen specific instances of acts of violence committed by Lester’s gunmen upon farmers and miners and their families in the neighborhood of the mine from the 15th of June to the day before the rioting when three union miners were killed by the mine guards. He characterizes these as “acts of oppression of challenge.” “They were provocative in character and we will show that they tried to provoke by this conduct, that they tried to draw the citizenship of this county into range of their artillery, that the avowed purpose was to assault, abuse, intimidate and, as a last resort to kill and murder in order to make tremendous profits and break up the miners’ union. For remember that the operators all through the country were watching the progress of the efforts in this county successful in his attempts to mine coal during the strike his tactics would have been adopted by other operators and the strike would Mr. Kerr said the result of these acts of violence and murder was to arouse the good citizenship of Williamson county, “a community,” he said, “rose up in defense of its homes. By this act of self-defense it served notice on the American gunmen and upon those who would employ the American gunmen, that this was not a safe community into which to send hired murderers.”

Gunmens’ Bloody Toil.

He then gave an outline of the history of the use of gunmen in labor disputes in this country. He cited 28 instances, beginning with the Homestead strike in 1892 and continuing through Cripple Creek, Colorado, Ludlow, Mingo county, W. Va., the Michigan copper, strikes, up to the present time.

He said in the cases cited more than 300 workers had been killed by gunmen who went unpunished for their acts. “This is the bloody background of the men who invaded your county,” he told the jury. “You are now asked to convict somebody in this case because some of these men lost their lives as the result of their invasion into this county.”

Defendants Not in March.

He accused the prosecution of having been “wickedly careless in the selection of their defendants. We will show you in this case that Otis Clark, Bert Grace, Joseph Carnaghi, Leva Mann and Peter Hiller not only had nothing whatever to do with the killing of Howard Hoffman or any of his associates Howard Hoffman or any of his associates at a time when it would have been physically but that they were in positions and places impossible for them to have had anything to do with it. We will produce here a great number of men of repute in their community who were standing along the line of march which led to the place of killing. They will tell you that not a single one of these defendants was in that march.” He concluded by quoting from authorities to show that the killing of Howard Hoffman could not be regarded as a single event but must be taken in connection with the circumstances preceding it.

Murderous Gunmen the Real Criminals.

“I have shown you,” he said, “from court decisions that even a lawful act, if calculated to excite disorder and cause breaches of the peace, becomes unlawful. Who brought on this difficulty? The men who first invaded this community, the men who piled crime on top of crime and finally took the lives of your own citizens.”

Private Influences Behind Prosecution.

“The state has told you that 2,000 people or more formed the mob, which killed the scabs. Out of 2,000 or more people the state has selected five whom they want to make victims. Why, then you ask, are these five indicted? Because the prosecuting authorities of Illinois yielded to private influence. Their place and their statute is taken by a private organization composed of men of great wealth, ‘The Illinois Chamber of Commerce.’ Actuated by a desire for vengeance, eager to do anything that will help to destroy organized labor. The Chamber of Commerce is the organization that prosecutes in this case. “You and you alone,” he told the jury, “stand between these defendants and this cry for revenge. Let the law be your support and let justice be your product. We want nothing more.”

The Voice of Labor was a regional paper published in Chicago by the Workers (Communist) Party as the “The American Labor Educational Society” (with false printing and volume information to get around censorship laws of the time) and was focused on building the nascent Farmer-Labor Party while fighting for leadership with the Chicago Federation of Labor. It was produced mostly as a weekly in 1923-1924 and contains enormous detail on the activity of the Party in the city of those years.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/vol/v11n580-jan-06-1923-VOL.pdf