Another fine piece of writing from Charles Ashleigh; this essay finds him among the unemployed of Chicago in the autumn of 1914.

‘The Job War in Chicago’ by Charles Ashleigh from The International Socialist Review. Vol. 15. No. 5. November, 1914.

HOISTING oneself by one’s own boot-straps is supposed to be the acme of impossibility, but that seems to be precisely what the capitalist system is doing at present. In its efforts to continually enlarge and to intensify its operations it is undermining its own existence by creating the elements which shall contribute to its downfall. That inevitable adjunct to rampant capitalism—the army of the unemployed—is steadily on the increase, and, just now, with the partial cessation of industry caused by the European blood struggle for markets, the problem is becoming still more acute.

It is interesting to mark how the attendant evils of the industrial system are extending all over the country. Last year, unemployed riots were not confined to the manufacturing East, but also broke out in San Francisco and other points on the Pacific coast. The boasted glory of the busy Middle West is sullied by the appalling numbers of workless ones in its hub, Chicago.

The Chicago Tribune, which is as conservative a journal as could be found, some time ago estimated the number of unemployed in Chicago as over 100,000 and intimated that they were increasing. According to trade union authorities, over 60,000 union men are out of work. These figures, however, certainly fall far short of the total. The United Charities report that they assisted 21,000 families in 1913, as against only 10,000 in 1910, and they maintain that the number is steadily ascending. It should be remembered that only a very small proportion of cases are reported to the charitable institutions and that a still smaller number receive aid.

Every day cases are cited that prove the depths of poverty and suffering in which large numbers of workers and their families are plunged. In the sumptuous automobile of a member of Chicago’s gilded minority was found a baby, thin and under-nourished, wrapped in a dirty gray rag, which was deposited in the vehicle while the owner was regaling himself in a cafe. A man was recently sentenced to six months in the Bridewell for stealing food; he had been out of work for several weeks and dependent upon him were his wife and two babies, one of them only one month old. The home of these free citizens of prosperous America consisted of a one-room, windowless shack, with leaky roof, and sanitary conveniences remarkable only by their absence. The conscience of our “altruistic” civilization was satisfied by the railroading of the unfortunate husband. Here the function of government ended and the succoring of the wife and children was left to individual charity, which in this case was attracted by the publicity the incident received. However, there is no complaint here implied; what have the workers ever to hope for from the agents of their industrial task-masters?

The principal question that agitates the mind of the unemployed, homeless worker,—where to sleep,—is becoming more pressing with the advent of the cold weather. Police stations are already full to overflowing, as are also the night shelters. To complicate matters, orders were issued recently by the police department for the dispersal of night loiterers. The minions of the law sallied forth in force on October 6th and routed out scores of unfortunates who were trying to snatch some broken sleep in freight or lumber yards, vacant lots, empty buildings and wharves. A force of police, with drawn clubs, drove a number of men at bay on the river front, after awakening them by the customary brutal methods. One or two among them had sufficient manhood to resent this treatment and offered some resistance to their persecutors. The police, revolvers and clubs in hand, attacked the defenseless band, rounded them up, and carried off some thirty to jail. The papers next day exploded with indignation, stigmatizing the offenders as “wharf rats,” while, on the next page, they were making fervent appeals to “Good Fellows” to come to the aid of this same class.

The large emigrant population of Chicago are especial sufferers. The shutting down,—or partial stopping of production,—of great industrial concerns employing hosts of foreign unskilled laborers has brought untold misery into the Ghetto, Little Italy and other foreign quarters. A case that came to my notice on October 5th is illustrative of this. Mrs. Annie Jarosz a Polish widow, was dependent upon work received from her more fortunate neighbors for her sustenance and that of her baby and two-year-old child. When the general financial tightening came about no jobs were forthcoming. Within a few days the baby was dead of starvation and the widow and her remaining child have been ejected for nonpayment of rent. One might waste oceans of “sob-stuff” in describing these incidents, but we will leave that to our well-paid lady journalists of the daily papers; we are not trying to stir the hearts of the affluent, but to induce the worker to at last determine to take the remedying of these conditions into his own hands.

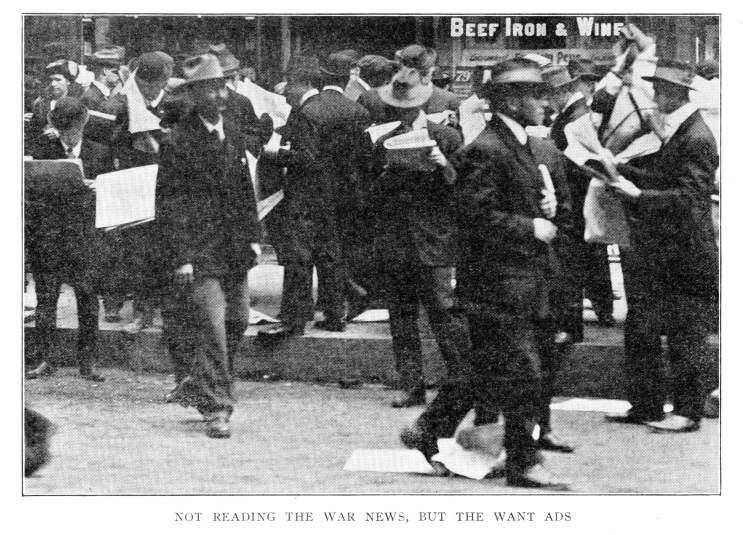

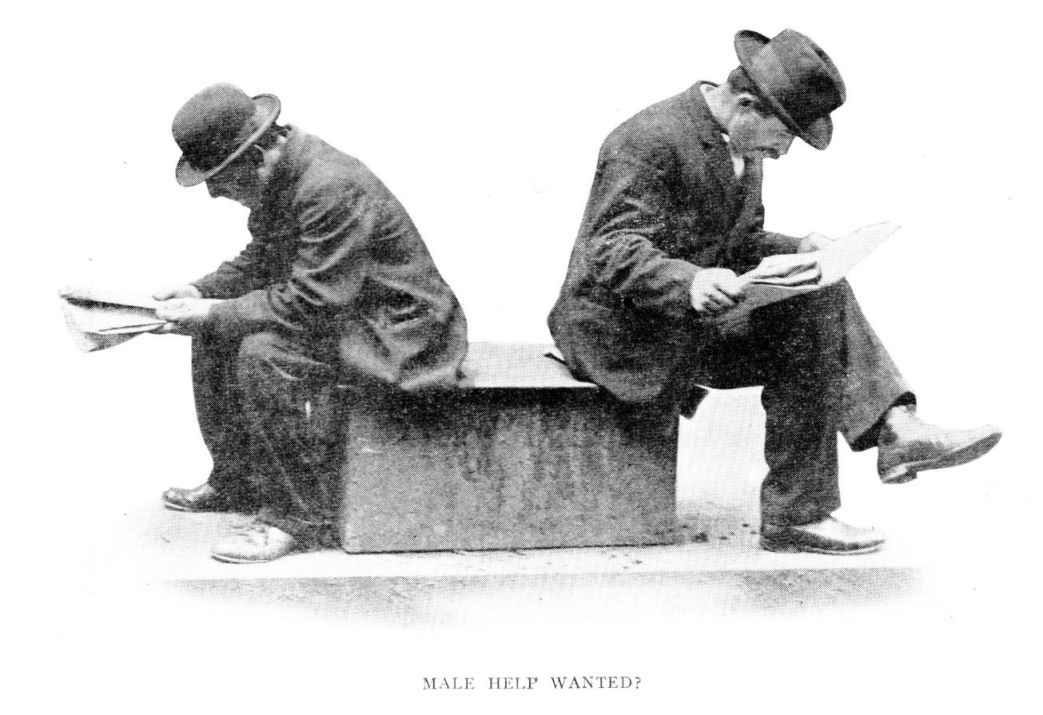

Besides the permanent industrial population of Chicago, casual workers are pouring daily into the town. Every freight train and passenger has its complement of jobless ones. These add to the number of job seekers and still further intensify the terribly keen competition on the labor market. In the crowded “Loop” district, thousands may be seen every noon awaiting the afternoon papers with their lists of offered jobs. When the newsboys appear they are virtually mobbed by the work-hungry crowds; and then comes a feverish scanning of the advertising sheets, and then a rush to be first applicant. One glance at the number of vacant positions in the paper and then at the size of the crowd will reveal the appalling difference in their respective, numbers.

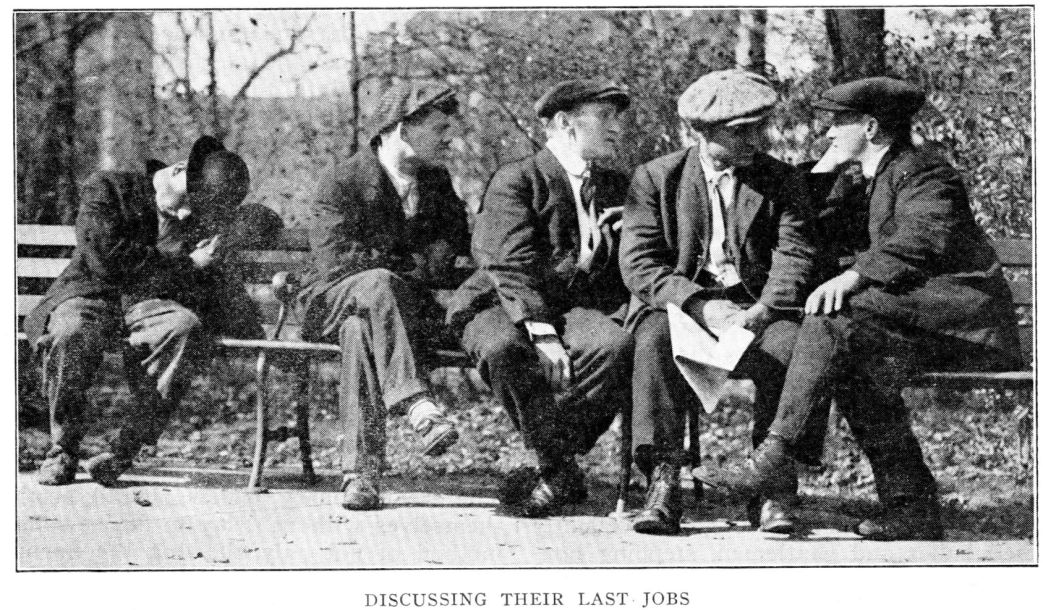

It is not always he of the tattered garments who is the greatest sufferer. A large number of those most unfortunate members of the working class,—the white-collared company of clerks,—may be seen filling the park benches. These have the additional disadvantage of having to maintain some sort of a respectable appearance. I noted one of this type, the other morning, arising from his night’s repose on a bench in a secluded arbor of Lincoln Park. A piece of newspaper was placed within his vest to protect his shirt-front and his collar and tie, carefully wrapped in paper, were beside him. He produced a small whisk broom from his pocket, and a comb, and made his pathetic toilet, not forgetting to polish his leaky shoes with the newspaper. He was not the type that dares to beg for a meal on the street and one could sense somehow that he had not the price of breakfast. I entered into conversation with him and discovered that he had worked in the auditing department of the Illinois Central Railroad. Two months ago he had been discharged on account of a cutting down of the staff and since then had found nothing but one or two odd jobs. I asked him whether he had been to the state free employment office. He said that he had and that once he had been dispatched to a residence to do odd jobs. On arrival there, he had been made to do some painting and other work which falls within the province of skilled labor and for which the current union rate is 65 cents per hour. For this he was offered twenty cents an hour. He was rather an unusual type of clerk because he refused to do the work; for which I honored this obscure hero of industrial warfare.

On the “Flats,” by the lake side, beyond the railroad tracks, may be observed groups of men washing their shirts and underclothing, in the effort to appear respectable and to rid themselves of the vermin with which the cheap lodging houses are infested. The possessor of a razor is also an exceedingly popular person at these gatherings. Looking westward from here, one sees the magnificent buildings of the clubs and hotels which line Michigan avenue where are also displayed the latest Paris costumes and the very cutest things from London in the line of walking canes and cravats.

And the well-dressed and excellently fed ladies and gentlemen, stepping nonchalantly into or out of their automobiles, are very possibly going to attend a meeting tonight in which the poor will be exhorted to recognize the benefits of thrift; and, possibly, the merits of cheese as a substitute for meat will be enthusiastically extolled, this being one of the latest fads of some of Chicago’s wealthy reformers.

On West Madison street, the stamping ground for the itinerant worker, the employment offices have all posted the sign “No Shipments” in their windows. The mission halls bear the announcement that lunches will be served free at the conclusion of the services and, most pregnant sign of all, the proprietors of the ten- and fifteen-cent restaurants are complaining bitterly at the slackness of business. The streets are full of men tramping with that wearied, hopeless slouch typical of the discouraged and underfed seeker after work, although usually they do not make their appearance until later in the year. Everything points to the coming of the severest and most extensive unemployed spell that this country has ever experienced.

And, what to do? We know the probable happenings of the approaching winter, if things be not altered. Bread riots, unemployed processions, marches to city halls, meetings in parks and squares and all the accompanying phenomena of hard, workless winters, characterized by a want of organization and a waste of energy which it is painful to see. And the proud aristocrat of labor, who happens to be holding on to a job, will not concern himself with the homeless one on the breadline or in the empty garrets of the Ghetto. But, when he is on strike, and some of these yield to the temptation of good food and a bed and take his place, then will he boil over with contemptuous anger.

The working class organizations, sooner or later, will have to realize their identity of interest with the mass of unemployed. They will have to understand that it is essentially to their interest that there be as few men as possible looking for jobs. The revolutionary bodies should bestir themselves without delay to devise some method of not only showing the unemployed how to secure for themselves the necessities of life but also the advantages and* absolute imperativeness of the solidarity of workers and workless. For the securing of food and shelter, petitions to governing bodies are worthless. The same amount of time, energy and sacrifice used in monster processions and meetings, with their consequent conflicts with the police, could be much better utilized in the taking by the unemployed of the things which they require. Wm. D. Haywood’s recommendations to this effect, at the recent convention of the Industrial Workers of the World, should be taken to heart by all those who do not wish to see the unemployed movement deteriorate into the means for the exhibition of flowery oratory.

It is up to the unemployed themselves to better their conditions; nobody else is going to do it for them. And it is most emphatically up to the man with a job, if only in self-defense, to aid them in every possible way to secure their ends. The unemployed are continually referred to sneeringly as “the mob.” Well and good; then the mob can and must be transformed into a coherent and conscious body, knowing well its economic position in society and the cause of it, and determined to go after the goods and to get them by any and all means.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v15n04-oct-1914-ISR-gog-ocr-NWU.pdf