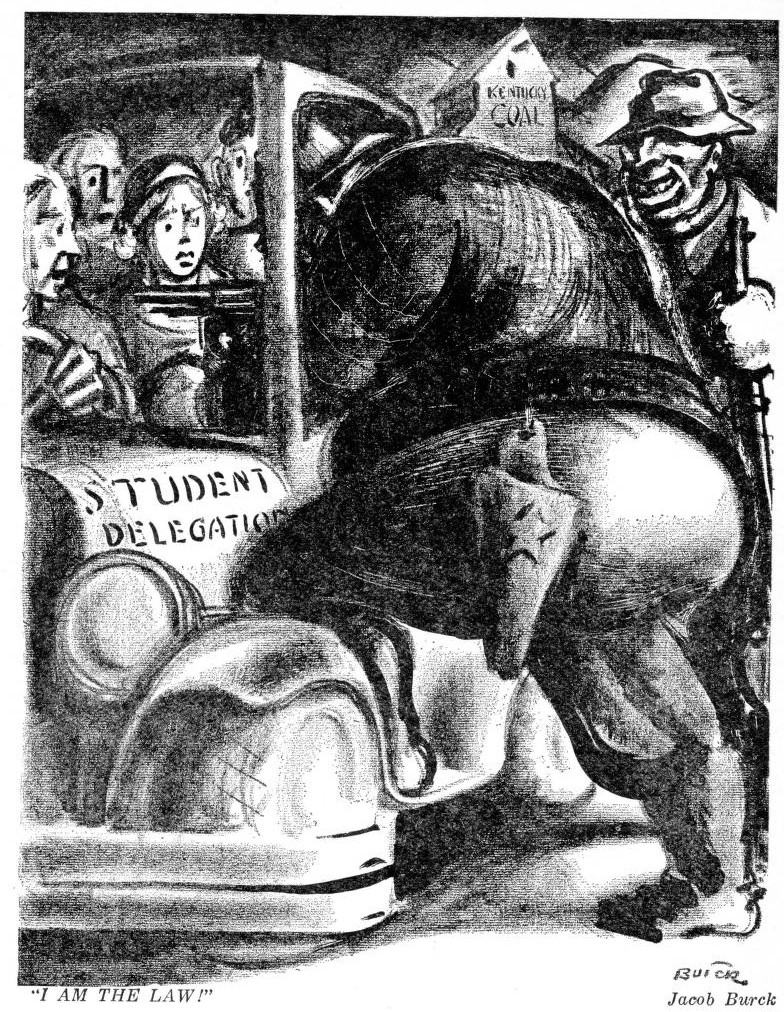

Students from Columbia University organized by the National Student League travel to Eastern Kentucky to deliver aid and investigate the strike in ‘Bloody Harlan.’ Unwelcomed by the local authorities, they receive an on-the-ground education in the class war.

‘Kentucky Makes Radicals’ by Rob F. Hall from Student Review. Vol. 1 No. 4. May, 1932.

I.

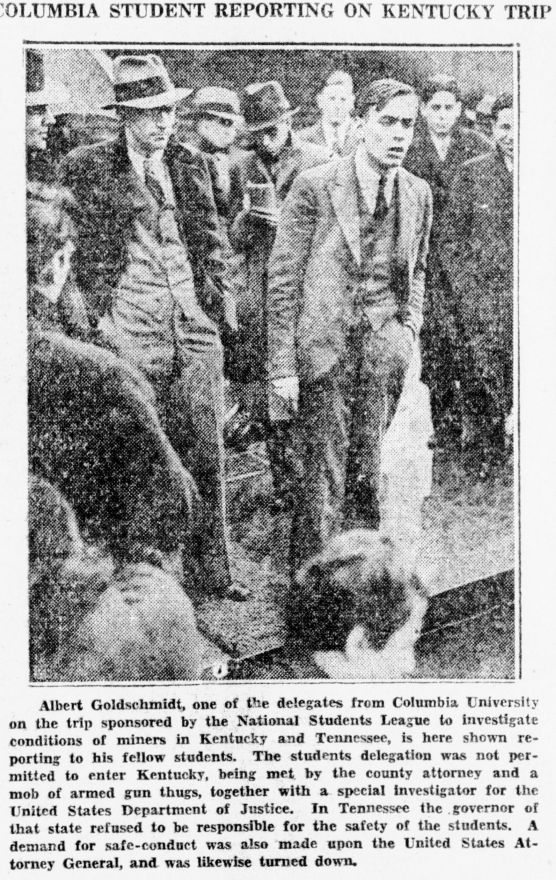

UNDER the auspices of the National Student League, eighty students with inquiring minds set out for the Kentucky coal fields. We were equipped with a set of questionnaires and plans to interview miners, coal operators, representatives of the Red Cross, local officials and the townspeople. We never got to see the miners whose conditions we had prepared to study; they were concealed from us by an army of deputy-thugs, who ejected us from Kentucky. We were insulted by the Governor of Tennessee and ignored by the Governor of Kentucky.

Did we affect in any way the conditions of the 15,000 or more miners in Harlan and Bell counties? Obviously the miners are still faced with hunger and starvation. Their children continue to die of flux because they lack sufficient and proper food. Attempts of the miners to preserve and broaden their National Miners Union, the only instrument for improving the conditions under which they live and work, are still met with the bullets and black-jacks of the coal operators and their faithful servants, the state and county administrations. The two miners who accompanied us as guides remain in a Bell County jail where they were thrown after they had been snatched from us, branded as “dangerous agitators, criminal syndicalists, members of the National Miners Union.”

An active campaign to collect from students and members of college faculties funds for the relief of the miners was started as a part of the preparations for the trip. This campaign has continued in many colleges and universities, and has been given a decided impetus, both on the campus and in the city, by the publicity which attended the student trip. The widespread newspaper comment, although it was concerned for the most part with the sensational aspects of the trip, with the fact that students had embarked on “a novel expedition” rather than with the condition of the miners, had value in that it helped attract the attention of other workers and students to the existence of these conditions. It may also be said that we encouraged the miners by showing them that thousands of students recognize their plight and will fight to help them. But important as such encouragement may be, we recognize that any concrete betterment of the conditions of the miners, such as the collection of more relief, remains for future reckoning.

One result of the trip, however, which we consider of tremendous importance, is that we, the students who made the trip, learned through our experience to see into economic and political realities and to comprehend a lesson which our instructors in economics and our professors of sociology had never taken the trouble, if they knew it, to impart to us.

When the group set out from New York we represented a variety of political and economic beliefs. The National College Committee of the National Student League issued its invitations to all students, irrespective of such beliefs, content with launching a general student laboratory in political science. As centers of this form of activity on the campuses, the Social Problems Clubs, Liberal Clubs, etc., were the first to respond, electing their delegates and setting to work immediately to raise funds to defray the expenses of their delegates. Those clubs which constituted chapters of the National Student League had already had some contact with working-class struggles. Many of the clubs, on the other hand, were no more than liberal discussion groups, and a number of the delegates were unattached students who had had no contact with either liberal or radical clubs. Several of the N.S.L. clubs, it may be pertinent to indicate, elected, by way of an experiment, students-at-large to be delegates. As a result, the students had in common only the fact that they were students, a rather indefinite interest in labor problems and a somewhat vague liberal sympathy with the working class.

The majority of us felt very little apprehension that we would be stopped or mistreated. Any difficulties we might encounter would come, we believed, from the hired gunmen of the mine-owners. If the sheriff and the county attorney were in league with the gunmen, as had been charged, we would appeal to the governor. If he failed us, there was always the federal government.

The story of our disillusionment is the story also of our “education.” The process by which we arrived at the underlying realities of the social and economic order is well defined in those steps which we took following our expulsion.

II.

THE protest which the students left with Governor Horton of Tennessee dealt almost exclusively with the fact that the constitutional rights of peaceful travelers had been violated. To Governor Laffoon, however, the students said:

“It is the desire of the students to lay before you the facts of their expulsion, the significance of this treatment insofar as it reflects the general conditions: in Harlan and Bell counties, and to call on you as chief executive officer of the state of Kentucky, to restore freedom of travel on state highways…”

Their statement came more to the point, however, when they pointed out that this denial of their right to see conditions in this focal point of industrial unrest was

“…prima facie evidence that the governmental machinery of Harlan and Bell counties is being unlawfully employed to prevent the existence of conditions in the mine fields, which cannot stand the light of study, from being disclosed to the outside world…The unlawful actions of the Bell and Harlan county authorities towards our students must apparently be but a small part of the terrorism to which the miners are submitted when they organize and strike against intolerable conditions. There can be no other conclusion from the forcible prevention of any endeavors at outside intercourse with the miners. A cordon of steel has been thrown about the Southeastern Kentucky coal fields. We would not have been kept out if there were nothing to hide.

“It is your bounded duty as chief law-enforcing officer of the State of Kentucky to put an immediate stop to this armed terrorism against peaceful visitors as well as—we have every reason to believe—against the miners of Southeastern Kentucky.”

When Governor Laffoon, after posing benignly with the students while the cameras clicked, refused to take any action, the students made the first step which might conceivably lead to action. They appealed this time, not to any arm of government, but to their fellow students and teachers throughout the nation.

“To the students and teachers of the United States,” their manifesto began, “We ask that you protest with us the reign of terror which oppresses the miners in the coal fields of Southeastern Kentucky. We appeal to you also to join us in demanding from the Senate favorable action on the Costigan resolution providing for a Senatorial investigation of the situation in the Kentucky coal fields.

“Our experience in Bell county during the past week has shown us that constitutional rights exist there only for those persons approved by the coal operators. For the independent person or for one who runs counter to the wishes of the coal operators, the constitution offers no protection or rights.”

The students then issued a message to the miners of the Kentucky coal fields. In addition to serving through its publication in the press to call public attention to the Kentucky situation, the message has the distinction, it is believed, of being the first public document to receive broad circulation in this country which united students and workers through an expression of common interests and pledge of solidarity. The statement said:

“We came to Kentucky to study conditions under which you live and work. We brought funds with us, collected from students and teachers, for the relief of striking miners and their families. Walter B. Smith and his deputies, and a mb incited to the point of violence, prevented us from seeing you and bringing relief to you.

“Some of us were beaten. All of us were subjected to force, gun rule, and intimidation. We now realize to what terrorism you are subjected. We realize that your living conditions, which the coal operators are afraid for us to see, must actually be at the starvation level. We know that the treatment they gave us is mild compared with what you are getting. We express solidarity with you and pledge ourselves to aid you in every way possible.”

Every effort was concentrated from that point on in bringing about the senatorial investigation provided for in the Costigan resolution. While such a hearing could not be counted on to bring the federal government into any fruitful action in the Kentucky affair, it was felt that the conditions of the miners and the extent of the coal operators’ terrorism would at last be spread out before the public. Perhaps the “cordon of steel” could be weakened and relief work expanded. If the pressure against the miners were released even for a short while, the National Miners Union could become stronger and effect in the end some improvement in starvation wages and intolerable working conditions.

The students proceeded at once to Washington where an informal hearing before Senator Edward J. Costigan was arranged. The Senator, an eagle-eyed praetorian, gave the student delegation the first show of cordiality they had received in many days. At his right sat Senator Logan of Kentucky, a southern politician. At Senator Costigan’s left sat Senator Royal S. Copeland of New York. Senator Logan was disposed to heckle, but he left early. Senator Copeland, representing a state from which a large number of the students resided, was able to remain for only a few minutes of the two-hour hearing.

The delegation proceeded to put upon the minutes of Senator Costigan’s committee the entire story of their visit to Kentucky and their ejection by Walter B. Smith, Deputy Lee Fleenor, the killer, and the other faithful servants of the coal operators. Their story, however, had taken on by now a meaning which the earlier recitals had lacked. Rights guaranteed by the constitution and rights which the federal government was obligated to uphold had been flaunted, they said. The abrogation of these rights was not a piece of spontaneous or impromptu lawlessness on the part of any individual; it was, on the contrary, a policy adopted by a ruling class which felt its power threatened by a working class growing restive under intolerable conditions. The testimony was summarized by the chairman of the student delegation as follows:

“These facts indicated clearly to us that the unlawful activity of coal field officials was not unpremeditated or planless actions along mountain roads. They were their normal methods of procedure throughout the county offices and even in the courthouses of the coal towns of Middlesboro and Pineville. These officials were at all times dominated by coal operators or coal mine attorneys who in more than one instance took command from sheriffs, and in Middlesboro, actually became the mouthpiece for the judge. We are therefore forced to conclude that the bitterness and disregard of constitutional rights…must be many times worse in situations involving the miners themselves. Miners have no recourse now except a federal investigation…In preventing us from entering the mining district the operators have clearly shown that they are desperately trying to keep from the outside world the knowledge of living and working conditions of thousands of miners, citizens of the United States and entitled to federal protection where county and state officials have so ruthlessly violated their rights.”

While this hearing was proceeding, Herbert Robbins of Harvard and Margaret Bailey of N.Y.U. were waiting in an anteroom of the office of President Hoover. They had with them a statement which said that the students are “compelled to believe that the plight of the miners who live their lives in Kentucky under the domination of these same officials and deputies, merits the fullest Federal investigation.”

The secretary of the secretary of the secretary of Mr. Hoover accepted the statement with the remark that it would be placed in the hands of the Department of Labor.

III.

To summarize, we had our “rights” violated (already we had begun to use quotation marks). We had seen evidence, where the miners were concerned, of sterner violations and a graver situation. We had taken our story to two governors, three senators, the president of the United States. A friend had taken it to the attorney general. Only in the case of one lone senator was there any show of interest in a situation which we recognized as intolerable, unconstitutional, and, in terms of our earlier values, inhuman.

Individually, in groups, and, at length, as a body we discussed the situation in the Coal Fields.

It was clear that the miners are virtually imprisoned, deprived of the freedom necessary to maintain their organization, denied any intercourse with those outside who would be their friends. This isolation, we saw, is maintained by a cordon of steel, an army of killers and a legal machine which effectively prevents this intercourse.

The forces which serve the mine-owners are the combined power of the Coal Field ruling class. In Southeastern Kentucky, the combination includes the county attorneys, sheriffs, judges, and the entire law-enforcing machinery. Thugs employed as deputies, including such killers as Lee Fleenor, comprise the strong arm. It is reinforced by Cleon K. Calvert, an attorney for the Wallins Creek Mine Co., and his American Legion boys; by Herndon Evans, editor of the Bell county newspaper, and the local press; by organized charity, and the Red Cross, of which Evans is director; and by the church and the clergy.

To this list we added Governor Ruby Laffoon who was forced to hear us—he received 3,000 telegrams during our visit to Kentucky—but who refused to take action for the safety of the miners, citizens of the state of Kentucky, or for citizens of the United States who might choose to invoke their constitutional rights to cross a state line.

Of the powers beyond the boundaries of the state which served the interests of the Kentucky coal operators, we immediately listed Sheriff Riley of Clairborne County, Tennessee, who had shown a fine spirit of cooperation toward the Kentucky gang. He had arrested 17 miners and N.M.U. organizers and lodged them in prison at Tazewell. It was

Sheriff Riley who had kidnapped Joe Weber, N.M.U. organizer, when he was enroute through Clairborne county to Kentucky. There was also Governor Horton of Tennessee, who refused to take action against the Clairborne County oligarchy, and who believed, and said as much, that any one who exhibited any interest in the plight of the miners must automatically be a dangerous red. In Knoxville, there was the Journal which had attacked the National Miners Union, had consistently espoused the cause of the coal operators, and treated the demands of the miners entirely in terms of a “red menace.” Although we were not molested at Knoxville—unless by molestation we include constant surveillance by plain-clothes detectives—the law enforcement officers of the city had raided on a number of occasions the officers of the Workers International Relief, arrested the relief workers and driven the organization underground.

In the failure of the federal government to defend that constitution which its officials had sworn to uphold we came to the core of the matter. The coal operators of Harlan and Bell counties include Ford, Morgan (U.S. Steel), Insull and Peabody. The government of the United States of America had no desire to take any steps which might embarrass the coal operators. The solidarity of the ruling class, employers, investors, and governments was revealed with all its implications.

Constitutional rights are a fiction. Democracy is a myth. The figures who sit in the seats of authority are not concerned with the denial of what we were once pleased to call civil liberties. And when the interests of the working class conflict with those of the employing class, the combined forces of government, press and church, come forward to suppress the workers.

The fascist regime in the coal fields, with its so palpable a denial of constitutional rights, its deafness to the interests or demands of the governed, might be, in its severe form, only a local situation. But we recognized it as a policy to which the ruling class will resort in any situation where the working class has grown restive.

At the same time, we saw more clearly that the only power which can crush such a blood-and-iron rule is the organized working class. We saw that the sort of social and economic order which we had so passionately desired will come only because a working class demands it.

We recognized, therefore, that our interests lie with those of the workers. This did not follow merely as a piece of abstract logic. It came because in our struggle with a section of the ruling class, we found ourselves fighting shoulder to shoulder with workers. The bonds which bound us to them were the warm human bonds of common interests and a common objective.

This was a profound lesson, but a heartening one. To the eighty students who participated in the expedition, it was almost an obvious one. Our problem became one of how to translate this message to our fellow students.

The message is one which is involved, not only in the Kentucky incident, but in every struggle against reaction and conservatism, in every fight for the interests and rights of students and workers. To spread this message is a major task of the student movement.

At this historic moment the student movement is making its first rapid strides forward. The economic situation is one which forces the student toward collective action. Campus clubs of old standing and newly organized clubs are coming to understand this common aspect of the struggle, and, with the National Student League as their standard, they are working towards a united revolutionary student movement.

Emerging from the 1931 free speech struggle at City College of New York, the National Student League was founded in early 1932 during a rising student movement by Communist Party activists. The N.S.L. organized from High School on and would be the main C.P.-led student organization through the early 1930s. Publishing ‘Student Review’, the League grew to thousands of members and had a focus on anti-imperialism/anti-militarism, student welfare, workers’ organizing, and free speech. Eventually with the Popular Front the N.S.L. would merge with its main competitor, the Socialist Party’s Student League for Industrial Democracy in 1935 to form the American Student Union.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/student-review_1932-05_1_4/student-review_1932-05_1_4.pdf