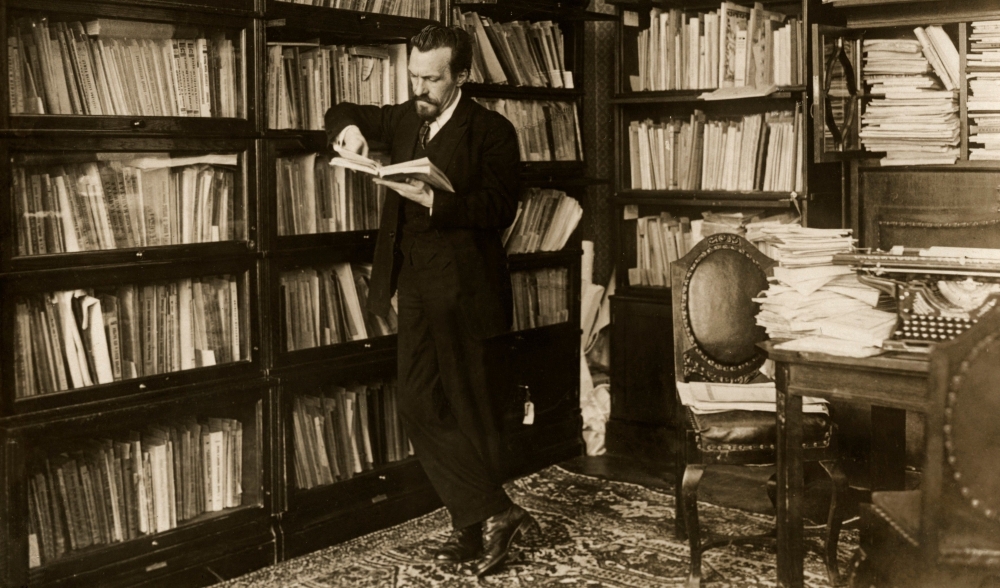

One of Rykov’s final speeches as head of government before losing his position as a ‘rightist’. Less than a year after the defeat and expulsion of the United Opposition in November 1927, the alliance between Stalin and Bukharin broke down as Stalin abruptly shifted course in response to that years harvest crisis, proposing grain procurement (which he personally oversaw in January 1928), and then mandatory agricultural collectivization, and rapid industrialization. In late 1928 leaders Bukharin, Rykov, and Tomsky spoke against the grain procurement, collectivization plans, and pace of industrialization. Rykov was, perhaps, the most conciliatory of the ‘Right’ leaders as the tone in this speech, dealing with the above issues, is evidence. However, by the time this speech was published the ‘Right’ had been decisively defeated at the April leadership meeting, with Rykov removed as Chair of People’s Commissars, a position he took over from Lenin after his death.

‘The Situation in the Soviet Union’ By Alexei Rykov from International press Correspondence. Vol. 9 No. 20. April 26, 1929.

(From the Report delivered at the Soviet Congress of the Moscow District.)

From our international position it follows that in the last two years, as throughout the whole period of the October Revolution, we have been forced to carry on the construction of the Socialist order of society by our own strength and means.

If during the first few years after the October Revolution the possibility of the organisation of a Socialist economy in our country was very seriously doubted, and if at the point of transition between the various periods of reconstruction these doubts recurred from time to time, we can now, not only on the basis of theoretical considerations, but also on the strength of actual experience, most emphatically maintain that we have all that “is wanted and suffices” for the organisation of a Socialist order of society and that, by preserving and consolidating the bloc of peasants and workers under the leadership of the proletariat, we shall be able to carry through the construction of Socialism to a victorious close. The experience of the last few years proves what substantial possibilities we have at our disposal for the growth of the socialised section of our economy and therefore for Socialist construction in general. In the development of our big socialised industries we have in numerous cases been able to attain greater results in practice than was provided for in our plans.

The Achievements of Systematic Economy and the Five-Year Plan.

The experience of the last few years likewise shows that in spite of our extremely bad organisation, in spite of the numerous shortcomings of our work, in spite of the tremendous bureaucratic abuses and of our preposterous technical and cultural backwardness, we have yet been able to attain an unprecedented rate of economic development. This experience entitles us to set ourselves yet greater tasks of construction and to attain incomparably greater results than hitherto in the organisation of our systematic socialist economy. The tangible programme which prescribes the main paths of our further advance, is the Five-Year Plan for the development of our national economy.

It would be a mistake to underestimate the intrinsic value of the fact that we have been in a position to establish a Five-Year Plan. It was only in 1925 that we first set up the figures for a one-year economic plan (and set them up badly at that); since then we have occupied ourselves energetically with the expansion and completion of the work connected with our schedule, which work resulted in various systems of annual figures of control and in several drafts of five-years plans. If we take this fact into consideration we must recognise that the present five-year plan for the development of economy represents a tremendous advance in our systematic economic work.

Our struggle for the Plan must not be taken to mean simply a desire for a good statistical table or for a scientific work in regard to economic subjects. The penetration of the “Plan” principle into our economy is a characteristic question of our struggle altogether. The tight for planned economy, for the better organisation of economy, for the growth of the socialised section thereof, for the most efficient and most efficacious influence on individual enterprises by the socialised section the fight for such an exploitation of experience and such a disposition in regard to economic forces, as would enable us to see very far ahead what lies in store for us and to secure our maximum of achievements not only for to-day but also for to-morrow such a fight is not a task to be settled all at once. That we should now possess a Five-Year Plan is undoubtedly a decided step forward. We had a plan before this, it is true. We had the plan of electrification confirmed by the Soviet Congress, which in the opinion of Lenin was as important as a second Party programme. In comparison with the plan of electrification, the Five-Year Plan possesses no fundamental directives in the sense of a technical readaptation of our entire economy. But it compares favourably with the plan of electrification inasmuch as it is a more tangible and more practical plan in regard to its contents. While the plan of electrification spoke of the approximate length of time (10 to 15 years) requisite for the realisation of a definite programme, we have now before us a draft-plan comprehending our entire economy and providing for a fixed (five-year) period of realisation.

With a view to characterising this plan I may quote some figures regarding the projected rate of development and those changes which will take place in the eventuality of a realisation of the Five-Year Plan.

Industrial output is to rise in five years by 115 per cent. according to the original form of the project and by 145 per cent. according to the most optimistic version. The total output of agriculture is to advance accordingly by 42 or 54 per cent., respectively. Capital investments in industry have been provided for to the extent of from 11,000 to 14,000 million roubles and in agriculture to the extent of from 22,800 to 24,000 million roubles (including the investments of the individual producers, the investments from the State budget amounting to 5,500 millions).

These are very substantial figures. If we read them for the first time, we involuntarily ask ourselves whether they have not been put rather too high and whether we shall ever be able to cope with such a programme. In the current year we are investing in industry some 2,000 million roubles (including electrification and other tasks). If the capital investment in industry were merely to remain at the same level from year to year, we should nevertheless have during the five-year period an investment of 10,000 million roubles. The figures projected in our five-year plan are in my opinion by no means particularly high, nor do I personally think that the main difficulty will be encountered in the realisation of the five-year plan in this direction. The changes which these capital investments entail, meanwhile, are quite remarkably great.

Besides the sum provided for investment purposes, the five year plan is based on important qualitative factors. The productivity of work in industry is to be increased by 95 or by 110 per cent., according to the two versions of the plan; the costs of production being reduced accordingly by 30 or 35 per cent. and the fuel-consumption per unit of output by 30 per cent. Are these qualitative alterations possible? I believe the volume of capital investments justifies these figures. The possibility of a realisation of these qualitative factors depends on that new equipment of our economy which results from the tremendous investments envisaged.

What does the five-year plan mean for all our workers and peasants in the direction of an advance in their prosperity? Every worker and every peasant may be sure that his standard-of-living will be raised. Wages are to rise by 50 per cent., the income of the agricultural population by 46.1 per cent. This will of course only ensue if all workers and peasants really effect the economic work prescribed. Every worker, every poor or middle peasant, must know that if he desires such an advancement of his welfare and such achievements in his fight against poverty, backwardness, misery, and ignorance, he must also attain by his work no less definite successes in the increase in working productivity, in the improvement of the quality of work, in the collective comprehension of the farms, and in the organisation of the co-operative enterprises. And this plan must be made accessible to the broad working masses. We must interest the many millions of workers and peasants of our country in its successful realisation.

The Five-Year Plan, the Present Difficulties, and the Grain Problem.

In what do the great difficulties of the plan consist? According to the findings of the November plenum of the C.C. they lie in the fact that “the extremely low level of agriculture. especially as regards grain, embodies the danger of a rift between the Socialist cities and the petty-bourgeois rural districts. thus endangering the main presumption of the Socialist adaptation of our entire national economy.” The present year, the first year of the five-year period covered by the plan, is faced with great difficulties and critical phenomena.

“The grain problem, the great lack of black metals and building materials, the dearth of commodities in general and the problem of reserves, an acute relapse in exportation and consequently also in importation, and finally the problem of currency stabilisation such (according to the establishments of the relative resolution passed by the November plenum) are the most essential sectors of the economic front which call for particular attention.”

It is not for me to enter into a discussion of all these questions of the present business position of our economy. The most important among them is the grain and foodstuffs question, which I shall only treat from the standpoint of the difficulties in the alimentation of the population and the introduction of food cards.

Why should both the Soviet Government and the local Soviets have had recourse at the present moment to such an expedient as the introduction of food cards? We were obliged to have recourse thereto, because in the case of a lack of any commodity the Soviet Government must in the first place consider the interests of the workers, both industrial and agricultural. The food cards are the outcome of a necessity which has arisen by reason of the insufficient development of agriculture in general and grain cultivation in particular. In case there should not be enough products available for all, the food cards are intended to safeguard the interests of the working population. This year both the Moscow Soviets and the local Soviets must start from the standpoint that there are still likely to be difficulties in alimentation. I say this in view of the possibility of complaints being voiced at this meeting in regard to the insufficient supply of bread in some district or other. To this sort of complaint I should answer, as I have answered all along, by declaring that this year we cannot yet give every one bread in unlimited quantities. This is not because we do not understand how to procure the grain from the rural districts, but simply because too little grain is being produced there.

Last year the curve of industrial production rose constantly sometimes in excess of the preliminary estimates while grain production developed at a slower rate. The total output of agriculture rose by 5.4 per cent. in the year 1926/27, relapsed by 1.1 per cent. in 1927/28, and will this year have to rise by rather more than 4 per cent. This growth, however, is mainly occasioned by the intensive development of the technically cultivated areas, the extent of which surpassed that of pre-war times by 50 per cent. The crops of the most important technically cultivated field products, it is true, have either not yet reached their pre-war level (flax, sugar-beet) or else exceed it only by very little (cotton). However, if we regard the grain cultivation, it will appear that the entire grain output in 1913 figured ad 81.6 million tons, that of 1926 at 74.5 million tons, that of 1927 at 78.3 million tons, and that of 1928 at 73.6 millions tons. The grain crops are thus fluctuating around the Same figure; the position in this respect has been unchanged for a number of years, whereas the population now amounts to 154 millions as against 140 millions in 1913, the progress of the poor peasant class meanwhile enhancing the demands of the rural districts and decreasing the quantities of grain on the market.

These difficulties increase in view of certain other factors of an elementary nature, as for instance the loss of the last Crops in Ukrainia and North Caucasia. As a result of these circumstances, the total harvest has decreased by about 200 million poods, which means that otherwise about 10 million more poods of grain would have been available on the market. Such elementary happenings contribute to complicate the process which for years past has been observable in agriculture. It therefore appears to me that the crucial point in the realisation of the five-year plan lies in the solution of that task which had the main attention of the November plenum of the C.C. of the C.P.S.U., the task of a general incentive for the advancement of agriculture. This must be clearly understood not only from the standpoint of establishing an equal balance in the development of certain branches of economy, of extending the normal circulation of goods between town and country, and of providing industry with raw materials, but also from the standpoint of furnishing the mainstay of industrialisation the country, the working class, with foodstuffs. The successful solution of the task of enlarging the sources of grain and other foodstuffs is the most elementary presumption for the speedy realisation of the plan of industrialisation.

New Energy in Agriculture.

The plan provides for a substantial exportation of grain at the close of the five-year period. This, again, presupposes progress in agriculture such as can only be attained in the case of a gigantic technical adaption of our backward agriculture. The peculiarity of the five-year plan of agriculture lies in the fact that the solution of the problem is sought from the standpoint of a connection between agriculture and industry. The most important thing required by agriculture for the purpose of advancing the output of the soil is means of traction. Without industry the possibility of increasing the volume of traction at the disposal of agriculture can depend solely on the natural augmentation of draught-cattle. Such an increase has physiological limits which cannot be overstepped. What can industry do for agriculture in this respect? It can introduce machinery, mainly tractors, a mechanical means of traction. A tractor is a form of traction which does not depend on natural conditions of increase but solely on the efficiency of our industry. Mechanical traction renders it possible to surmount the restricting limits of the natural increase in draught-cattle.

Often, very often, we speak of industry being the leading element in our economy. In the five-year plan this general term “leading element” is analytically divided into such tangible elements as can be individually treated. In each case it is possible to establish quite exactly what great advantages and what possibilities for development lie for agriculture in the great engineering industry. Without this basis, without the penetration of this new form of energy into agriculture, the problem of reconstruction cannot be solved. So far we have not yet a single properly working tractor factory, our backwardness in this respect being altogether unparalleled. Therefore the rate of development we have adopted is by no means particularly rapid from the standpoint of the present state of affairs and from the standpoint of the terrible backwardness which prevails in our economy. If we rely merely on the natural increase in our head of horses, the necessary growth of agricultural productivity will not only not be realised in one, but probably not even in many, five-year periods.

Collective Farms, Soviet Estates, and Individual Farms.

The wholesale penetration of the new sources of energy into our agriculture, the broad use of tractors, and other complicated machinery, the transfer from mediaeval methods of work to a scientifically organised agriculture all this presumes an increase in the units of production. It is thus quite comprehensible if the five-year plan has devoted much attention to the construction of Soviet estates and collective farms. The rate at which Soviet estates and collective farms are to be created has been put pretty high, but even at the close of the five-year period the individual farms will still represent more than 60 per cent. of the total output of marketable grain and about 90 per cent. of the actual total of grain production. The 40 per cent. of marketable grain which we shall then be receiving from the Soviet estates and collective farms, will nevertheless provide such a possibility of influencing all agriculture and will play such an organising role in the rural districts that the entire proportion of forces and the entire working conditions and relations both in the villages and between the towns and villages respectively, will have to be radically changed. This, however, will only be the case at the close of the five-year period. The next few years, meanwhile, will be the most difficult in regard to the backwardness of the agricultural basis.

It is therefore quite obvious what an enormous importance attaches now and will continue to attach to the general incentive for an increase also in the individual output of goods, by the promotion of the individual farms of the small and middle peasants. While keeping a straight course towards collective farming and contributing to the active promotion of the development of the Socialist elements in agriculture, we must not lose sight of the fact that with a view to overcoming the present difficulties we must make sure that all steps we take in the direction of introducing new technical aids into agriculture, of supplying means of production (machinery, seedcorn, fertilisers) and agronomic aid, and of extending the area under cultivation, will be gladly welcomed by a peasantry, especially a poor and middle peasantry, which is economically interested in such measures. It is only by such a combination of our aid for the peasantry with our fight for the extension of the socialised section of agriculture, that we can secure the economic interest of the individual producer the peasant farmer and can hope to consolidate the alliance between the working class and the main mass of the peasantry, thereby enhancing the possibility of a speedy industrialisation of the country, a speedy transformation of agriculture on the basis of collective wholesale production, and a successful offensive against the kulaks, the capitalist elements in agriculture. With a view to improving the position on the agricultural front, the Government has taken a whole number of measures, raising the grain prices last autumn, and issuing a law in regard to the increase in the production of the soil and a new agricultural tax law.

What index-figures are at present available with reference to the state of agriculture and the state of the seed-crops? The Central Statistical Office has calculated that in comparison with last year the autumn sowings have decreased by about 3 per cent.; in regions where the harvest is below the average this relapse is yet far greater. Thus the area under cultivation on individual farms in North Caucasia has decreased by almost 15 per cent. and in Ukrainia by more than 11 per cent. The collective farms and Soviet estates in these regions show a substantial growth of their areas under cultivation (in North Caucasia by 150 per cent. and in Ukrainia by 46 per cent.). This growth, however, could not make up for the recession in the cultivation on the individual farms. The average total recession was 16.6 per cent. in North Caucasia and 10.4 per cent. in Ukrainia. The lack of fodder in consequence of the bad harvest led in these districts to a considerable decrease in the head of cattle.

The prospects for next year will depend on the success we shall be able to attain in the spring campaign. For the spring seed-campaign the Government has this year provided 40 million poods of seed-corn, i.e. about 10 million poods more than last year. A very great increase is noticeable in the provision of agricultural machinery for the rural districts. All those serious difficulties which we are experiencing at present must be overcome in a very short time, seeing that they impair the entire circulation of goods and the entire economy of the country. It is therefore comprehensible that the forthcoming spring seed-campaign will have a very energetic character.

The gravity of the questions in connection with the present economic situation may by no means lead us to neglect the less momentarily urgent tasks of a socialisation of agricultural production.

This attitude in the development of agriculture, of which I have already had occasion to speak, combines the five-year plan with the alteration of the social conditions and proportions in the rural districts. If we compare the problem of to-day with that which prevailed a few years ago, we shall immediately see the tremendous difference. The main difference lies in the fact that the questions of enlarging the productive units in agriculture and of introducing the methods of collective agricultural cultivation were then discussed without any particular experience in that direction. Such things had then not yet been tried; they were not even approved of by the peasantry and did not yet attract such wide circles of peasants as now organise themselves for the purpose of collective farming. During the last two years the problem of enlarging the productive units on the basis of socialisation was transferred from the region of theory and resolutions to that of wholesale practice, with a participation not of single individuals but of hundreds of thousands. Relying on experience and on the growing importance of the new forms of energy, the Planned economic commission is planning such an enlarging of the socialised section as will enable us to exercise a far greater transforming influence on economics, on the social and class conditions and on the daily life of our extremely backward rural districts.

On the Light and Heavy Industries and the Quality of Work.

The above characteristics of the prospects of agricultural development, the need of agriculture in the way of mechanical traction such as is requisite for the lasting improvement and transformation of peasant economy, goes to prove that the policy of industrialisation we have carried out is necessary and indispensable. I shall not attempt here to deal with all the big and complicated questions, which are involved in the development of industry. I shall merely mention the question of light and heavy industries, which at one time gave rise to considerable misgivings. It is now being solved in such wise that the development of the heavy industries (or to speak more precisely, the industry producing means of production) is carried on at a quicker rate than the development of the light industries. The reconstruction of our entire economy must find its expression in a tremendous augmentation of the volume of the best possible means of production, which will help to enhance the productivity of collective socialised work. The means of production, however, whether intended for agriculture or for the big or smaller industries, are mainly made of metal.

In our country there is, however, a great lack of cast iron the result being that we have not been able to produce the adequate number of machines and tools for all branches of industry, for socialised and for individual work. Without a solution of the cast-iron problem there can be no question of industrialisation. Cast-iron is the universal raw material for industrialisation and for the enhancement of the productivity of work.

When I visited the factories during the Soviet election campaign at Moscow and heard the presidium of the Moscow soviet criticised for what I admit was an inadequate provision of commodities on the part of municipal economy, I openly declared that such a criticism was not always justified. For the inadequate growth of the budget of the Moscow Soviet it is not Comrade Uchanov (chairman of the Moscow Soviet Ed.), but I who am to blame.

Comrade Uchanov and other comrades of the Moscow Soviet have often told me that the budget of the Moscow Soviet is inadequate and that electors have drawn attention to various shortcomings, which it would cost too much to set right. It is however, not in view of its too small budget that the Moscow Soviet cannot defray these expenses. These long discussions ended in my suggesting to the Government that the budget of the Moscow Soviet be still slightly cut down. In visiting the most recent election-meetings, I have had frequent occasion hear both non-party and Communist workers in the Moscon Soviet criticise the fact that the hospitals are badly served, that there are few doctors, few teachers, few dwellings, that in the one case the drains, in another the water-supply, and in yet another the means of communication are worthless.

We must naturally give the workers good drains and taps and means of communication. But if we are to do this in any proportion to requirements, it will be of no use raising the budget of the Moscow Soviet by a few million chervonetz. For the purpose of constructing a water-supply system or of carrying out a drainage system we require pipes, while for laying tramway lines we need rails. And this material, these pipes and rails and things, our factories still produce in an altogether inadequate degree.

The workers who criticise the Moscow Soviet are right when they point to what is generally wanted, but they are wrong to they think the matter can be righted by the allotment of money for the immediate satisfaction of certain desires. To build a water-supply system, to build drains or a tramway system, dwellings, or what not, we require cast-iron, both for the construction of rails, tubes, girders, etc., and for the production of machinery with which to furnish all factories and economy general. But we have neither the cast-iron nor a sufficient number of factories. The enhancement of the prosperity of the masses, and the improvement of public services (as of the services of the Moscow municipal economy) thus depend not merely on money but also on our material resources. Their limitations also limit the growth of the municipal economy, the welfare of the working class and that of the peasantry. There is only one way of enlarging the material resources and that is the forced development of industry, the construction of new factories and the growth of agricultural output.

Our mistake in regard to the question of industrialisation lie in the fact that we have hitherto not understood the ways of making this problem so comprehensible to every worker and every peasant that all may know that the improvement in the standard-of-living, their victory over poverty and ignorance can but be derived from one thing only, namely, industrialisation. It is on the success we achieve in this direction that the prosperity of the entire population depends.

If in the question of grain and the other problems of the rural districts we have succeeded in carrying out such measures as the raising of the price level, the new agricultural law on the increase of output, and the like, the most important Government decision in regard to industry of late, apart from the confirmation of the control figures and the distribution of the capital investments among the various branches of economy, has been the law regarding the consolidation of working discipline.

This question has been sufficiently enlarged upon. I should only wish to point out that its solution is connected with the question of prime costs. It is a well known fact that the reduction of the costs of output by 7 per cent. must according to the annual plan yield some 700 million roubles for the construction of new factories and works.

If we are to be enabled, therefore, to make pipes for the drainage of our cities and rails for our tramways, we must provide the money by a reduction in the costs of production. This dependence is sometimes lost sight of, improvements being demanded in municipal management without corresponding demands being put forward in regard to the increase in the productivity of work. The one without the other is impossible. The reduction in the costs of output must yield about 700 million roubles. In the direction of working discipline and organisation, a considerable number of shortcomings are to be recorded of late. Cases have been reported of working discipline not only not having increased but having sunk considerably, entailing a regression in productivity. There have been instances of rowdyism in the factories, the willful damaging of machinery, and the like. Therefore the Government has been induced to issue a special law in this regard. Besides a series of other circumstances, the fact must be taken into consideration that the working class is being augmented by elements from the villages and from the petty-bourgeois circles in the towns, individuals who have not been through the school of work and who have not been trained in working discipline and class-consciousness in the factories and works. These workers from the villages often consider their work in the factories a temporary matter; they hope “to save money and take it back to the country”. That is the background of the negligence and lack of discipline which it is our duty to overcome at any price.

The Reorganisation of the Administration and the Cadres.

Finally, I should like to say a few words as to bureaucracy and as to the improvement of the activity of our apparatus. I have briefly sketched those prospects which are prescribed by the five-year plan. From this characterisation you could see what the next five years are to bring in the organisation of things if I may express it so the organisation of the processes of production in the country, the organisation of agricultural output, the creation of new giant works of the type of the Dnieprostroy Combine, the Rostov agricultural-machinery works, the Stalingrad tractor-works, the factories of Telbes and Magnitogorsk, and the like. There must be great changes in technics, tremendous alterations of the forces of production. It would be a great mistake to believe that all these tremendous changes in economy can be effected without organisational changes and without influence on that system of organisation in our staffs and those methods of work which we at present employ. The termination of the regional division of our country and the establishment of the five-year plan, the execution of which occasions great alterations in the economic geography of the country all this creates a situation in which the old administrative methods prove unsuitable. And even if we consider only the one fact, viz. the way in which we have solved gigantic problems in industry and in the organisation of industrial combines in the last few years, it will be apparent that the demands of economic life no longer suit into the frame of the present Governmental administrative apparatus.

We are forced to have recourse to other methods. Thus the question of the development of our chemical industry called forth the organisation of an institution like the present Committee for Chemicalisation. To settle the question of exploiting the Dnieprostroy current, again, we convoked a special council of 150 experts. The five-year plan raises all the questions of technics, science, and technical reconstruction onto a higher level. The process of affairs is now very often such that somewhere in the Supreme Economic Council, or in the trusts, or in the sections of the Systematic Economy organs, technical questions are solved, the problem then passing on to those who understand less about it; these quarters discuss and study the questions at issue for an interminable time and then pass them on to others for decision. Sometimes the matter in question is carried to the very highest authorities, so that I have had to occupy myself with such questions as determining the efficiency of a certain apparatus, deciding the number of cylinders for certain automobiles, and the like.

Our organisation is such that we who are versed in matters of social politics and class warfare, in regard to the proportional strength of the classes in economy, in regard to economic politics, and in the principles of the organisation of Socialist society, are called upon to decide questions such as whether automobiles are to be constructed with four or with six cylinders.

The changes in the realm of organisation must lie not only in the promotion of all representatives of science and technics but also in a far more drastic decentralisation of administration than has obtained hitherto.

When the five-year plan was established, a certain concentration of the administration in a centralised sense was requisite, so as to ascertain what was most necessary from the standpoint of the general interests of the Union and on what the money at our disposal should in the first line be expended. Now that we have the five-year plan, we must reserve to the central organs the general right of disposition in regard to the guidance of economy under the plan system. of the operative rights and duties they must be relieved to the greatest possible extent. The termination of the regional division of the Union will greatly facilitate the administration of the country and enable us to pass over to a broader and more elastic system, to a certain decentralisation of our administration.

One of the ticklish points of the five-year plan is the question of human material. We are experiencing extraordinary difficulty in supplying the work of industrialisation and construction with the requisite cadres of technicians and experts. In five years our industry requires 25,000 new experts. whom we are not in a position to supply. Among the difficult problems of the five-year plan, the significance of this problem must not be under-estimated.

This question of cadres, of the training of experts and qualified workers, is an organic part of the plan of industrialisation. To build a metallurgical factory we need people to plan it, to erect it, to put it into operation, and to conduct it. And I must admit that this side of the problem has not received the amount of attention which is its due. There is much to be desired in regard to the cadres of qualified workers. In connection with the construction of a great enterprise, which is to be put into operation in three years’ time, I recently had occasion to put the following question: “Now you know the intended dimensions of this enterprise, the number of workers it will require, and what qualifications will be expected of them. Can you also tell me where you are going to take these workers from and who will be responsible for furnishing them with the necessary qualifications?” To this fairly simple question I received no answer.

We have workers’ faculties, technical schools, and numerous institutions of various kinds. But all is so dispersed and so little in keeping with requirements that great damage may be expected to result if matters are not soon improved in this respect. In one of our newly-erected factories we made the experiment of having one shift composed of workers procured from Germany and another composed of Russian workers operating the same machines. In the German shift the machinery: worked all right; in the Russian shift something invariably happened to interrupt the even flow of work. If we project the construction of a great metallurgical factory, to be put into operation in three or four years’ time, we have time enough to prepare the necessary qualified workers and to provide them with practical experience in the existing metal-works. The question of the cadres of qualified workers will naturally be. easier to solve than the question of the technical experts; it only requires that degree of attention which is its due.

The difficulty of realising the five-year plan, which is altogether comprehensible in the early stages of the construction of a new order of society, is a difficulty that can be overcome and that will be overcome if all the problems of our economic development and our State administration are at the same time the problems which all our workers have at heart. The successful execution of the five-year plan presumes the recruiting of the broadest masses of workers and peasants for¡ the discussion and solution of the big problems at issue. We constantly start from the fact that our State is founded on the alliance between workers and peasants under the leadership and hegemony of the revolutionary working class. If, starting from this alliance and from the relation of class forces, we inquire whether in this new period of development of our economy the presumptions for a strengthening of this alliance will grow, we must declare quite categorically that a proper solution of the tasks of the five-year plan will enable us to extend and consolidate these presumptions to such a degree as was never witnessed before. Think of the main stages in the relations between the working class and the peasantry. The first stage was that of the war-alliance, the second stage was on the basis of the introduction of the new economic policy, the first step towards the reconstruction of economy on those lines which were already treated prior to the war. The period in which we are at present must supply the working class with the instruments of a yet greater and better political and economic leadership by means of industrialisation; it must provide it with such possibilities of a really material assistance as will enable the alliance between the working class and the great mass of the peasantry to grow and strengthen. (Vociferous applause.)

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly.

PDF of full issue: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uva.x002078458