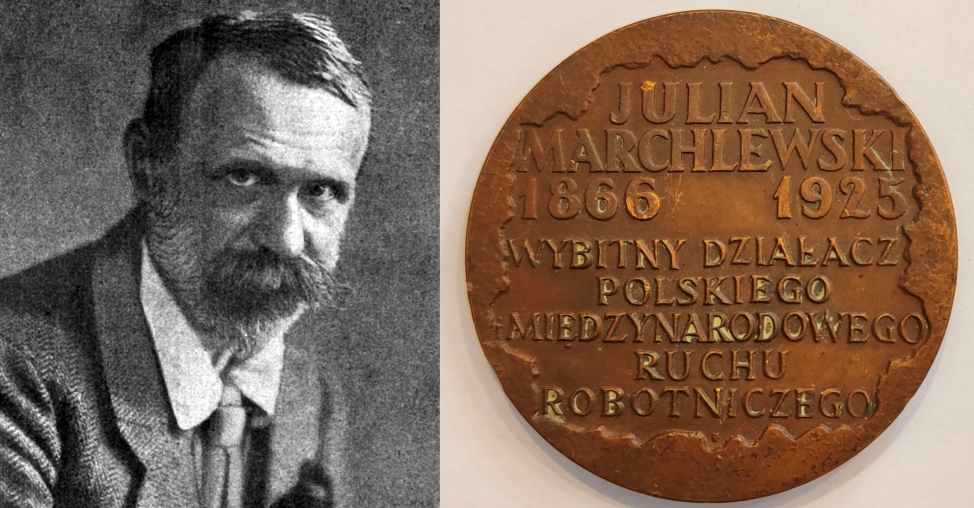

Julian Marchlewski was among the closest and oldest comrade to Rosa Luxemburg and Leo Jogiches. The three formed a political bond during their 1892 exile in Zurich, where they founded the Social Democratic Party of the Kingdom of Poland together. Here he looks at a decade of Socialist work in Poland, than under Tsarist rule.

‘Socialism in Russian Poland’ by Karski (Julian Marchlewski) from The Worker (New York). Vol. 13 No. 13. June 28, 1903.

Its Ten Year’s Labor, Its Sufferings, Its Foes, and Its Achievements.

“There is in Poland one thing of which the Russian government Is afraid even more than of the dissatisfaction of the Catholic Church–that is Socialism.” However curious it may seem, the comparison of “revolutionary qualities” of the international Catholic Church–which, by itself, never had in Poland any revolutionary tendencies– with international Socialism, yet in this opinion, expressed by Mr. Georg Brandes in the year 1886, we see that even seventeen years ago the political significance of Polish Socialism was evident to all observers of Polish life.

It was so seventeen years ago when Socialism, as a popular movement, had but appeared in Poland, when there was no strong organized party ceaselessly spreading the agitation and leading the movement. At last, in the year 1893, different Socialist groups united into one Polish Socialist Party.

And since that time Polish Socialism, in which hitherto, in spite of its external revolutionism, economic tendencies preponderated, acquires the features of the definite political movement. The new united party puts forward as its program the abolition of the Russian invasion and the establishment of the independent Polish Republic.

It is now ten years since the Polish Socialist Party was established, ten years of hard struggle in conditions unheard of in any of the countries of Western Europe. And the progress which has been accomplished during that time, although perhaps not so brilliant as one would desire proves that the future of Poland belongs to Socialism

As there is in Russian Poland neither freedom of speech nor freedom of press, the propaganda of Socialism is confined to the formation of secret societies and to the distribution of Socialist literature. But as the propaganda by means of literature smuggled from abroad did not satisfy all the needs of the growing movement, the Polish Socialist Party started in 1894 the secretly printed Journal “Robotnik” (The Worker”). Those comrades who were engaged in organizing the secret press estimated that the clandestine press would stand the publication of ten or twelve issues of “Robotnik,” and would then fall into the hands of the gendarmes. The reality has out-grown these expectations, as the journal went on appearing for years, and only in 1900 our “editorial offices and establishment” have been seized by the police. However, the seizure of this press has not interrupted the continuity of the publication: another press was immediately established and the publishing of “Robotnik” is going on till to-day and, let us hope, will go on secretly up to the time when we shall be able to publish it quite openly. Recently we printed the fiftieth issue of “Robotnik.” Fifty issues of a journal in nine years! Such fact may seem entirely insignificant to those who are accustomed to read fresh Socialist journals every morning at breakfast table. But people acquainted with the secret press know that it is for the first time in history that a clandestine journal has run such a number of editions. By the same party press “Gornik” (“The Miner”), the paper for the workers of mining districts, is published together with occasional papers for different provincial towns. Freedom of speech being suppressed, the party expresses its opinion on every question of political or social importance by means of hundreds upon hundreds of handbills and leaflets issued by the secret press.

With time the “publishing department” was extended. In 1902 a clandestine journal in Yiddish was started to spread Socialism among the Jews and teach them solidarity with the Polish proletariat. To this increase of publishing activity within the country corresponded the development of literature published abroad; in 1898, in addition to the monthly “Przedswit,” appearing since 1881, was started the popular scientific quarterly “Swiatlo” (“Light”), afterwards turned into a bimonthly; in 1900 a new monthly, “Kurzerck,” was started, giving news of foreign politics and the Socialist movement abroad; in 1898 a Yiddish quarterly was started to meet the increasing needs of the Jewish proletariat; last year the Polish Socialist Party began to publish an irregularly-appearing paper, “Walka” (“Struggle”), for the use of Lithuanian provinces, and a bi-monthly, “Gazeta Ludowa “People’s Gazette”), for peasants and land laborers, who still form a majority of the population in Poland. Numerous pamphlets in the Polish, Yiddish, and White Ruthenian languages help in the great task of the political education of the masses.

Statistical data, representing the quantity of all publications, will hardly ever amount to tens of thousands, and by its numbers will certainly not impress English Socialists, accustomed to see pamphlets printed in hundreds of thousands. But if you will look upon these modest thousands of our pamphlets from other points of view, if you will remember that Polish Socialists, in distributing all this literature, cannot make any use at all of the post office, parcel post, etc., but have been compelled to organize something of the kind of their own–a Socialist post service throughout Poland and throughout the Polish western frontier; if you will see how our pamphlet goes from hand to hand until it is completely worn out and unreadable, you will see that the “social efficiency” of thousands of our literature is perhaps greater than that of hundreds of thousands in countries enjoying the freedom of the press, and at least corresponds to the “social cost” of our propaganda.

And this “social cost” of our propaganda is enormous. Prisons and Siberia take every year a heavy tax from the ranks of the party. I have not in hand the data concerning the number of victims. In the last two years, but the following statistics may give to the render an idea of what is the “social cost” of working for Socialism in Poland:

In the year 1895, forty-two comrades were committed for aggregate sentences of ten years of hard labor, thirteen and one-half years of prison, seventy-seven years of exile to Siberia, forty-one years of Northern Russia, thirteen years of exile from Poland.

In the year 1896: One hundred and eleven comrades for forty-eight years of hard labor, fifteen years of prison, one hundred and thirty-two years of exile to Siberia, twenty years of Northern Russia, one hundred and ninety-four years of common exile.

In the year 1897: Fifty-four comrades for seven years of prison, eighty-seven years of exile to Siberia, eighteen years of Northern Russia, sixty-six years of common exile.

In the year 1900 nine comrades were condemned to death, which sentence afterwards was commuted to hard labor in Siberia, each individual from ten to twenty years. In that year about two hundred comrades were condemned to various terms of prison and exile to Siberia and Russia.

From among the prisoners but few were able to escape from, or on the way to, Siberia. To this small knot of lucky Individuals belong two out of four persons arrested in connection with the clandestine press of “Robotnik.”

The Russian government, seeing the increase of revolutionary propaganda, applies again and again prosecutions, and devises new kinds of administrative machinery for crushing the organization. The corps of gendarmes and secret police are increased; in Warsaw, parallel with gendarmes a special force of local political police (“ochrana”) has been formed: a special contrivance of Russian administrators–“the factory police”–was set to work: in every factory there are a few officials whose only occupation is the supervision of workmen and discouraging them from forming any combination. Every strike of workmen meets with the staunch opposition of the government: this method comes sometimes even to this, that during strikes having any chance of success, Russian governors expressly prohibit factory owners from making any concessions to labor. In such conditions every workman must become a Socialist; we in Poland do not even understand how a distinction can be drawn between a Labor movement and a Socialist movement a distinction so apparent in England. The policy of the Russian government tends only to instill into the minds of people the conviction that first of all they must get rid of the dominion of the Tsar; and everyone understands that in such surroundings the class war must develop into the struggle for political independence. Herein lies the secret why our propaganda, in spite of all prosecutions, continually goes forward and finds acceptance by the masses.

Since the year 1890 the Polish Socialist Party determined to celebrate the First of May and called on the workers to make that day a general holiday. The celebration of the First of May, started in that year, was observed, in spite of all obstacles and prosecutions, by thousands of workmen. In 1898 a new step was taken, and in order to celebrate the international holiday, a public meeting and a procession organized. To the inhabitants of a country where all public gatherings are quite free, a demonstration does not seem to be anything extraordinary. But the significance of May Day demonstration In Poland, where all things are prohibited, and the impression of it on the spirit of the people, can only be comprehended when we take into consideration the fact that such demonstrations have not taken place since those held in the year 1862, on the eve of the last revolution. The May Day demonstration, originated in 1898, takes place now every year, and year by year the number of demonstrants increases; neither Cossacks’ charges nor the arrest of hundreds of people can prevent the workers from demonstrating their dissatisfaction with the existing order. What is more, demonstrations and different forms of celebration of the First of May have spread from Warsaw over the provinces, marking everywhere the progress of Socialist propaganda. As we have already said, it is only about a year ago that the Polish Socialist Party began the work among the peasantry and village laborers. The success of this work may be measured by the last First of May being celebrated in some villages. This simple fact proves that the village, the same village the lukewarmness of which towards all political movements was hitherto considered by Russian statesmen as the surest base of Russian rule in Poland, is now ready to accept anti-government teaching.

Beyond the struggle with political and economical oppression, the Polish Socialist Party leads a constant struggle with the Polish “conciliatory party”–as those few people are called who support the Russian government–with Clericalism, Antisemitism, and Nationalism, which, as everywhere, form the necessary attributes of modern, bourgeois society. The Catholic clergy, who in bygone days had been openly or silently opposed to the Russian rule, now turn into defenders of the “established order,” use their pulpits for denouncing Socialism, and sometimes simply co-operate with gendarmes in ferreting out Socialist agitators. Nationalism, denouncing the principle of the class war as “being entirely out of place within a nation overrun by foreign oppression,” tries to overlook all discord existing between Polish capitalists and Polish workmen, to hush it up by phrases about national solidarity and, in practice, to subdue the interests of the enormous majority of the nation to the interests of the well-to-do class. Antisemitism, encouraged indirectly and perhaps unconsciously by different sorts of Polish and Jewish Nationalists, and directly by the Russian government, tends to create animosity between two races living together, and in such way to turn the popular discontent into channels quite harmless to the stability of the government. Against all these unhealthy tendencies the Polish Socialist Party must fight and also against serious dangers threatening the emancipation of the proletariat of all nations inhabiting the territory of Poland.

Yes, of all nations inhabiting the territory of Poland. Because, beside the Poles who form the great majority of the population of the country, there are living side by side with them White-Ruthenians, Lithuanians, Ruthenians, Jews. The past history of these nations was common, the present lot is common, and the must fight in common for their future, Socialism, and Socialism only can unite them and give them the strength necessary for breaking the sway of Russia.

Ten years of constant work towards the realization of this aim have passed away. The past work, when summed up shortly, has consisted of “mere agitation.” But this agitation tended to revolutionize human minds, and only when this revolution of human minds is completed may we proceed towards the expression of it in outward political changes. How soon the progress of the agitation will allow us to undertake the actual preparation of the armed outbreak–that is the question which begins to gleam on the horizon of our practical politics, and which surely will demand definite answer before another ten years have passed. At present one thing is quite sure–that we will start the revolution when we shall have all chances of success. We look upon the Insurrections of 1831 and 1863 as upon unsuccessful experiments which in every branch of human activity precede the successful result. These past revolutions of ours have taught us how the revolution is not to be done: surely, we shall not begin, as in 1863, having in hand six hundred sporting guns. And in the preparation of the armed outbreak which will bring us the Independent Socialist Republic, we shall make use as well of the experience of past generations as of the enormous revolutionary forces of our people revealed by the ten years’ labor of the Polish Socialist Party.

The Worker, and its predecessor The People, emerged from the 1899 split in the Socialist Labor Party of America led by Henry Slobodin and Morris Hillquit, who published their own edition of the SLP’s paper in Springfield, Massachusetts. Their ‘The People’ had the same banner, format, and numbering as their rival De Leon’s. The new group emerged as the Social Democratic Party and with a Chicago group of the same name these two Social Democratic Parties would become the Socialist Party of America at a 1901 conference. That same year the paper’s name was changed from The People to The Worker with publishing moved to New York City. The Worker continued as a weekly until December 1908 when it was folded into the socialist daily, The New York Call.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/the-people-the-worker/030628-worker-v13n13.pdf