A founder of the Niagara Movement, Barber was editor Atlanta’s ‘Voice of the Negro’, one of the nation’s leading Black papers, who went to Chicago after the 1906 pogrom. There his radical journalism ran him afoul of Booker T. Washington whose machine had him dismissed from Chicago newspapers and Philadelphia schools. As an N.A.A.C.P. leader he proposed a regular pilgrimage to the grave of John Brown and his comrades in the mountains of northern New York where the Brown family lived in the multi-racial farming community of Timbuctoo. Participating in the emotional ceremony was Lyman Epps, a child of Timbuctoo who had sung at Brown’s original 1859 funeral.

‘A Pilgrimage to the Grave of John Brown’ by J. Max Barber from The Crisis. Vol. 24 No. 4. August, 1922.

JOHN BROWN was born on May 9, 1800, and was hanged on December 2, 1859. This year marks the 122d anniversary of his birth, and the 63d year since his death. In discussing the life of John Brown with my good friend, Dr. J. Theodore Irish, last winter, he remarked that it seemed singularly ungrateful that the Negro had never shown any special honor to this great friend of the race. The thought struck me as being a serious indictment against our people.

Here was a man who devoted his fortune and the fortunes of his family to the cause of freedom, and who finally gave his life for that cause. Here was a man who had more to do with the emancipation of the Negro than did even Lincoln—for in the final analysis, public opinion ended slavery. Abraham Lincoln was not a leader of public opinion on the slave question. His heart was wrapped up in the Union, and he wanted it saved with or without slavery, although he had seen that a nation half slave and half free could not long endure. That was before he was elected as President and before the web of politics had hedged his free opinion. John Brown saw at the beginning and saw at the end that slavery was wrong, an unclean thing in the world. It should be eradicated at all costs. It was eating away the heart of American ideals and arresting the progress of civilization, it brutalized the slave and the master. It handicapped America in her bid for the moral leadership of the world. A vampire people had accomplished the ravishment of a race. To this old Puritan the time for cajoling and temporizing with the unclean thing had passed. The fester had to be lanced.

He gave his life for this idea. Time has proved that this old prophet of stark and sheer vision was right. Within less than two years after his death, at Charlestown, the blue-clad armies of the North were marching to the tune of “John Brown’s body lies mouldering in the grave, But his soul goes marching on.”

If John Brown had not died, the soul of the North would have slept on in a dead dream, and slavery would have tightened its grip on the nation’s throat.

Why should Negroes forget this knight who heard their cry of distress and was lured to the gallows for their liberty? We would that this should not be. I brought the matter to the attention of the Philadelphia branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. They voted unanimously to send a pilgrimage to lay a wreath on John Brown’s grave on the occasion of his next birthday. Dr. T. Spotuas Burwell, the vice-president of the local organization, and the writer, were selected to make the pilgrimage. Both of us are busy men, but we felt that the sacrifice should be made and so we went.

Our information about Lake Placid, where John Brown is buried, was limited. We had had letters from the town clerk, from Miss Alice L. Walker, a colored woman who runs a sanitorium for tubercular people at Saranac Lake, and from Rev. Robert L. Clark, pastor of the Methodist Episcopal Church where the night meeting was held. We had also secured a letter from the New York State Conservation Commission giving us permission to hold services at the grave. John Brown’s farm is now owned by the State of New York, and is kept up as a memorial to the old abolition hero.

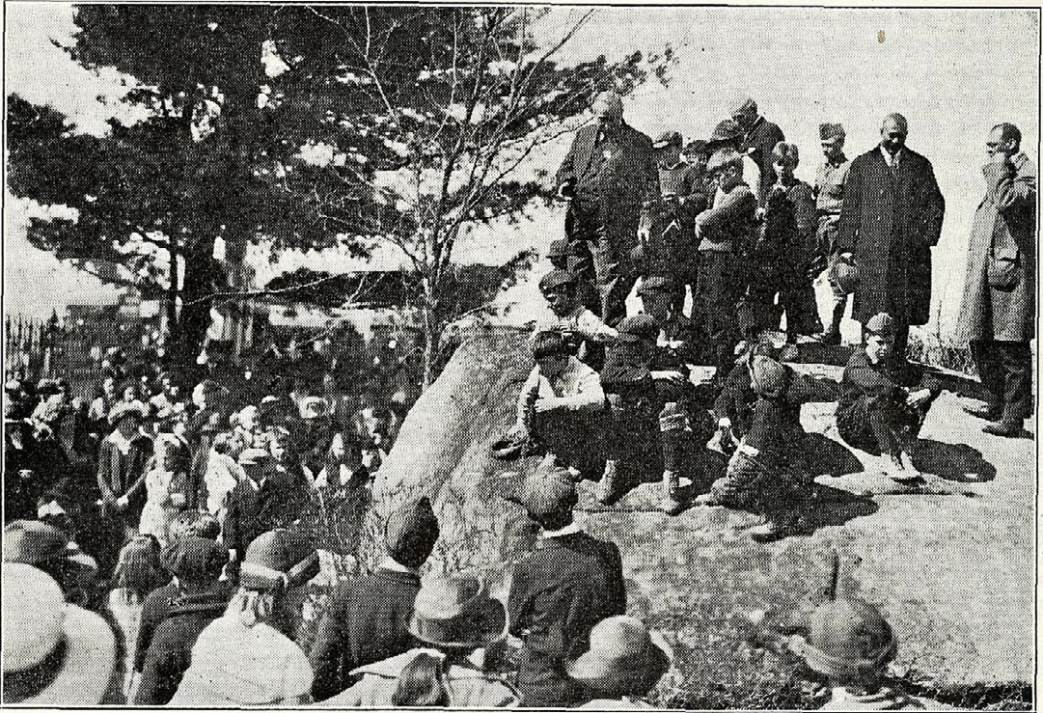

Dr. Burwell and I anticipated no crowd at the grave. We had said that we would count on Miss Walker, perhaps Dr. Clark, and possibly a half dozen colored people. There are hardly a dozen colored people in the two towns of Saranac and Placid. Fancy our surprise to find when we reached Placid, that the public schools had taken a holiday for the occasion, the Chamber of Commerce sent a delegation to welcome us, and the distinguished people of the town came out to be at the memorial services. There were perhaps one hundred and fifty automobiles parked around the grave and a thousand people there to do honor to our hero. The school children walked the three and one-half miles to be with us.

John Brown is buried beneath the shadow of a great rock. The writer spoke to the people from the top of this rock. The burden of his address was a call for another John Brown to attack lynching, Ku Kluxism, disfranchisement, and Jim Crowism. A magnificent wreath was laid on the grave.

One of the surprising features of the occasion was the way we were received. Among our audience was a judge from the town. We had present lawyers, doctors, school-board members, and members of the aristocratic clubs. Old soldiers embraced us. Men who knew John Brown wept for joy that this long-deferred occasion had come. Our photographs were taken by a dozen cameras. Even a movie camera was there. School girls took pictures for their civic class. Our pictures are now on sale as souvenir postcards in Placid, and at the caretaker’s place on the farm.

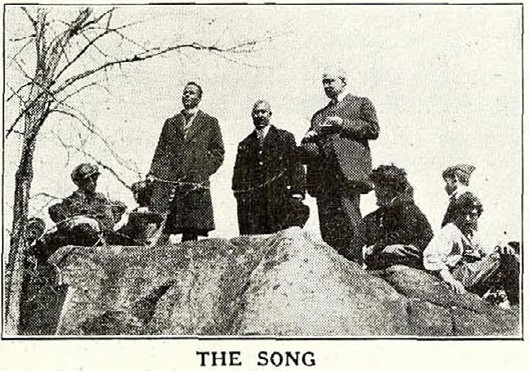

One of Brown’s sons sent a letter which was read. Byron Brewster, who was reared in John Brown’s family, welcomed us, and Lyman Epps, a colored man who as a boy in 1859 sang in a quartette at John Brown’s funeral, sang two verses of the same hymn.

At night, memorial services were held at the M.E. Church, of which Rev. Robert L. Clark is pastor. The people insisted that we make an annual pilgrimage to the grave, and they are especially desirous that on our next trip we bring a Negro quartette. At our night meeting, Dr. Burwell made a strong statement of the objects of the National Association, linking it up with John Brown’s old league of Gileadites. The occasion was indeed a most inspiring one and we cannot possibly forget it. The Rev. J.A. Jones of Oneida happened to be in that neck of the country, and was glad to be present at the services. Without the interest and co-operation of Miss Alice L. Walker and Rev. Robert L. Clark, we could not have possibly made the occasion such a success.

The Crisis A Record of the Darker Races was founded by W. E. B. Du Bois in 1910 as the magazine of the newly formed National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. By the end of the decade circulation had reached 100,000. The Crisis’s hosted writers such as William Stanley Braithwaite, Charles Chesnutt, Countee Cullen, Alice Dunbar-Nelson, Angelina W. Grimke, Langston Hughes, Georgia Douglas Johnson, James Weldon Johnson, Alain Locke, Arthur Schomburg, Jean Toomer, and Walter White.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/workers/civil-rights/crisis/0800-crisis-v24n04-w142.pdf