‘Van life’; luxury for one class, hell for another. Living in a trailer or out of car became widespread in the 1930s. This ‘solution’, which created more issues that it solved, to housing and job migration during the Great Depression has become a permanent fixture of working class life since. Elvar Wayne on its origins.

‘Housing by Trailer’ by Elvar Wayne from Pacific Weekly (Carmel). Vol. 5 No. 20. November 16, 1936.

Automobile trailers are potentially a housing menace, and the fact that they are being produced in large numbers is evidence of a diseased social order unable to provide jobs and proper housing for its working population. Those workers who can afford them are buying or building trailers in an effort to escape high rents and slums. Some advocates of better housing and slum clearance are seeing in the recent development of automobile trailers a solution for housing people whose incomes are less than $1200 a year.

A recent March of Time film exhibits contemporary developments in the trailer industry, reveals several models embodying ingenious designs, and suggests that these trailers might be the answer to a deplorable housing situation. A Nation article, “Resettlement by Trailer,” by Ernestine Evans, August 15, 1936, grows lyrical over the thought that trailers may mean the emancipation of the working class from slums and landlords, and suggests that the Resettlement Administration experiment with these movable homes rather than subsistence homesteads and camps for workers.

The manufacture of luxury, or “yacht,” trailers is assuming the proportions of big business. Factories are working twenty-four hour shifts turning out models which range in price from $500 to $5000. It is estimated that 300,000 units will be produced during the next year. Recent models resemble a small modern apartment in regard to furnishing and up-to-date equipment. They have everything from refrigeration to built-in toilets. Well-designed and appointed, constructed of fine wood or light alloy metals, these modern trailers are ideal for solving the housing problem on vacation tours where sleeping accommodations are bad or expensive.

Hotel bills may be avoided, and a family of two or three persons can live in comparative comfort in the most desirable locations along the way.

Such trailers might be all right for short camping trips, but they were never designed for year-round living quarters, and like most luxuries they are meant for middle class consumption.

The main value of the automobile trailer would be to house migratory agricultural workers in warm climates. Industrial workers, however, are concentrated in sections of the country where year-round living in trailers is impossible. In some sections of the South and California, the automobile trailer might conceivably offer an escape from present wretched housing conditions for the migratory worker. Unfortunately, however, it is hard to imagine how migratory worker families, whose present annual incomes are generally less than $500, could afford a trailer, even with cheap government loans. The low-priced mobile units are not built to withstand continuous usage for many years, and those of better construction are simply out of reach, costing as much as a well built cottage. Furthermore, it takes an automobile in pretty good mechanical condition to haul a trailer weighing a ton or more around the country. Most automobiles owned by low-paid workers have difficulty in moving their own weight.

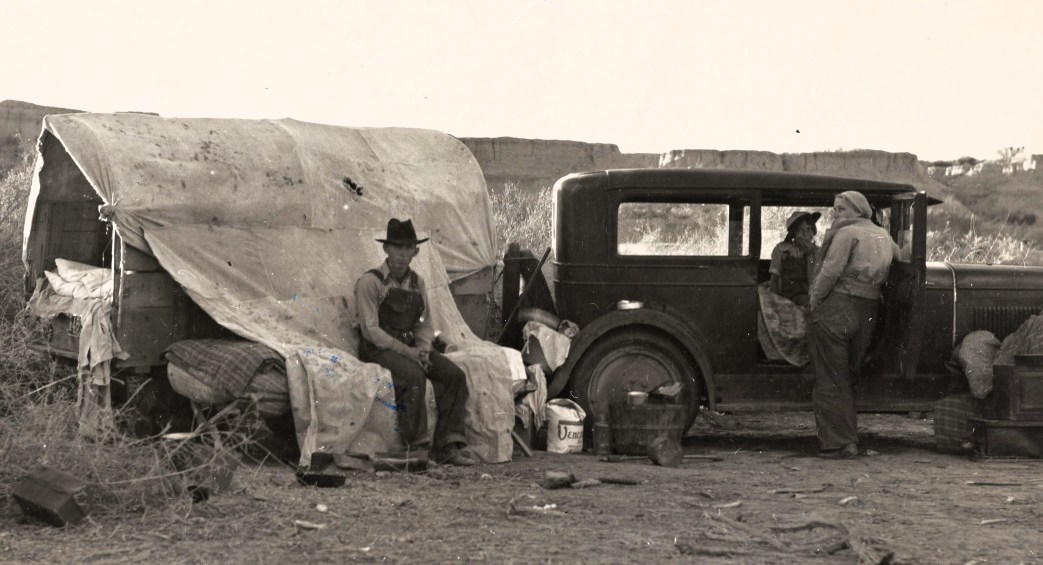

Thousands of American families since 1929 have been forced out of their homes and farms on to the open road. They migrate from city to city or from state to state in search of employment. Often with their last few dollars they purchased an old trailer or built a “house” on the chassis of their broken-down automobiles and started the great hegira to escape starvation. Thousands of them gravitated to California where the climate is generally suitable for all-year camping and where seasonal crops require nearly 200,000 migratory workers.

For the migratory worker in California automobile transportation is indispensable; he must move quickly from crop to crop, often at great distances. He may go as far north as Oregon and Washington for fruit picking or as far East as Arizona to chop cotton. If he has a house-car, the problem of living accommodations is greatly simplified, especially since migratory workers’ camps are generally unfit for human habitation. Hundreds of agricultural workers in California already have trailers designed for living which are old, dilapidated, often home-made and notoriously lacking in comfort. One sees them along the highways or parked in roadside camps. Their numbers have been swelled by recent migrations of the dispossessed into the state from blighted areas in the Southwest.

Unfortunately many migratory workers with trailers have been stranded in “Hoovervilles.” They have been unable to find work; their car has broken down; or they have become disabled through accident or sickness. Some have been stranded so long that they have sold parts of their automobiles to buy food or other necessities, or their cars have become useless through exposure to the weather over a period of months, and now the trailer has become a permanent habitation.

In many of California’s numerous “Hoovervilles,” trailers are to be found in significant numbers. Accurate statistics on the number of these trailers used by migratory workers for dwellings do not exist. In many “Hoovervilles” about one-third of the families live in mobile housing units. The State Department of Motor Vehicles in 1935 registered over 95,000 trailers, but these figures do not specify housing trailers. It may be estimated conservatively, however, that at least 2000 families live in trailers all or the greater part of the year. In the vicinity of Sacramento live nearly 3000 persons in squalid “Hoovervilles” along river banks, near dump heaps and swamps, and a recent survey showed that about one-fourth of these depression victims dwell in trailers or house-cars. Some of them have been there from three to five years.

The trailer dweller has some advantages over the average “Hooverville” inhabitant in the matter of choice of location. If this machine still functions he can move to a cleaner more segregated camp than a person without a portable dwelling. But even with this advantage of mobility, his movement is circumscribed and his location confined to certain areas, which are generally inhabited by other depression victims.

There is not much choice between present trailers used by workers and the average “Hooverville” shanty as suitable living quarters. Generally the trailers are inhabited by families, whereas a majority of the shacks shelter single persons. Additional space can always be added to a shack, but a trailer cannot be enlarged, hence overcrowding is more peculiar to the latter than to the patchwork huts.

Many house-cars and trailers house from four to eight persons in less than one hundred square feet of floor space. The average dwelling on wheels is seldom more than fourteen feet by seven. Many workers’ families who inhabit them have communicable diseases, and one often finds small children cramped in these quarters with tubercular parents. In good weather, of course, beds for older children can be made under the trailer or out in the open.

Most of the house-cars and trailers owned by migratory workers are badly constructed with almost no inside furnishings. A few are equipped with inefficient stoves; some have

collapsible tables and beds; and some have facilities for inducting water and electric current. But few of these families can afford electric bills, so candles and lanterns furnish light. Windows are small and admit very little sunlight.

Hundreds of families dispossessed by the depression have come to look upon such housing units as permanent habitations. In many respects the owners are worse off than other depression victims, for they have less chance of getting relief than other unemployed persons, since they move about whenever they can in search of employment and therefore seldom meet residence requirements for relief. In California it is the custom in many counties to give these migrants one meal and enough gasoline to move on to the next county. They are shunted around from one locality to another until their automobile breaks down or until they find a community more hospitable than the one departed from.

Many migratory workers built or purchased trailers in order to have better living accommodations than are provided by agricultural employers and to escape paying exorbitant rentals often charged in migratory camps. Now, perhaps, with the advent of trailers on a mass production basis, the cure may become worse than the disease. The thought is not pleasant that, with the passage of years during which the manufacture of these “dwellings” may reach 500,000 annually, used-car lots will be stacked with mobile miniature tenements for American workers. Until decent living accommodations and jobs of a more permanent nature are provided for workers in states requiring a large number of migrant agricultural employees, the automobile trailer, as a health and housing problem, will be potentially a social menace.

Pacific Weekly, based in Carmel, California was edited by William K. Bassett, Lincoln Steffans, and Ella Winter from late 1934. A Popular Front-era ‘fellow-traveler,’ magazine that became more of a Party press over its life. With a strong literary and arts focus, something of a West Coast ‘New Masses’, the weekly did not survive long after Steffans death in June, 1936. Though its run was short, Pacific Weekly is a rich record of left-wing 1930s writing with authors like publishing work in its pages.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/ccarm_008430/ccarm_008430_access.pdf