November 7, 1917 was the seizure of power in Petrograd; but the Revolution took place over several years and was spread, deepened, and defined in the Civil War. A very useful summary of the war and the differing character of its fronts from Soviet Russia’s military analyst Roustam Bek. Bek (Boris Tageyev) was a former Tzarist soldier and Social Revolutionary who became a military journalist for European papers, and a supporter of the Bolsheviks, being the Red Army’s representative in the Soviet’s U.S. mission. After the closing of the mission he return to Soviet Russia and continued to write military histories.

‘Three Years of the Red Army’ by Col. B. Roustam Bek from Soviet Russia (New York). Vol. 3 No. 19. November 6, 1920.

THREE years of glorious fighting for the Revolution have passed. Three years of super-human sacrifice on the part of the Russian working class have just terminated, and still Soviet Russia is ready to enter upon a new epoch of struggle, high-spirited and fully equipped with decisive determination to defend all the gains which the Revolution won during the three sanguinary years.

The victory of the Revolution was gained by the Red Army only because, by its structure, its morale, and its methods of warfare it is absolutely different from all other armies.

The secret of the extraordinary successes of the Soviet Government can be explained by the fact that the Red Army never was a so-called “people’s army”, or a “national army”. It was and is an army of the working-class, fighting for the reconstruction of the whole social system. Class criteria were introduced in the Red Army, and in spite of the cooperation of the former officers of the Czar, it remained an army of the workers and peasants, and can not give way to any reactionary transformation. The experiences of the past three years have proved that absolutely.

Soviet Russia has a regular army,—her enemies also possess regular armies. Soviet Russia, in order to create her army, mobilized the masses, so did her enemies. The Red Army is chiefly composed of peasants, while the armies of the Allies and the Russian reactionary generals are also composed of peasants. Thus it appears that the armies of both sides are made up of similar elements. Then wherein lies the difference between the Red Army and the armies of its enemies which gave the victory to the former?

The Red Army of the workers and peasants is led by workers, by the most class-conscious revolutionary Communists, and there is a close connection between the men and their comrade-commanders. Quite the contrary can be said of our enemies. Their armies are led by officers who are most conscious representatives of bourgeois interests. Therefore, the progress of the struggle unites and tempers the Red Army, while in the capitalistic armies it results in disorganization and collapse, a truth revealed during three years of armed intervention and civil war in Russia.

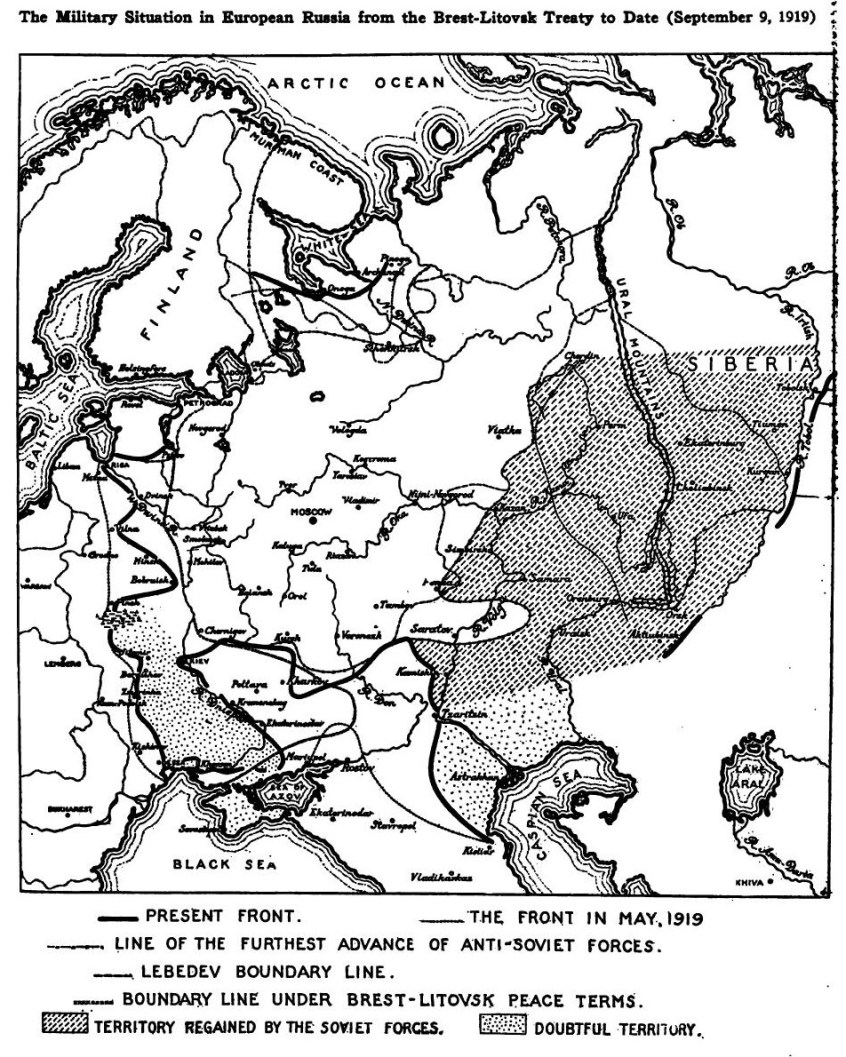

Three years passed for Soviet Russia in uninterrupted fighting on several fronts. At one time during 1919, there were in Soviet Russia thirteen battle-fronts which I described in Vol. I, No. 13 of this weekly (August 30, 1919). As in a kaleidoscope, one after another, the enemies of the Russian proletariat appeared and vanished before the Red Army. Kornilov, Krasnov, Dutov, the Czecho-Slovaks, the “people’s army” of the supporters of the Constituent Assembly, Kolchak, Yudenich, Denikin, and the Allied invaders, all were defeated. The Poles were weakened and in exhaustion were forced to enter into peace negotiations with Moscow. The bourgeoisie of Finland, Esthonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Rumania lost faith in their capitalistic supporters, and preferred peace with the Soviets to the useless sanguinary struggle against the Russian proletariat The former thirteen fronts are now reduced to one, the Crimean front, where the last act of the bloody drama is drawing to a close.

In this review I can give only an outline of each front separately, basing my information mostly on official documents which have at last reached here from Moscow. In many cases they confirm statements previously made by me in Soviet Russia, with regard to the civil war in Russia; but since the receipt of these important data from Moscow, with real military maps, and long and detailed descriptions of battles, I can now see clearly what I could only guess at in the past.

The Northern Front

The Northern front deserves special attention. There the reactionary forces, though a small part was of Russian origin, were predominantly of a purely foreign character.

This front grew out of British intervention in Russian domestic affairs. It was Anglo-French strategy which organized and mobilized the fighting forces on this front by sending Allied troops there. It was after fruitless attempts to force Russia to continue the war with Germany for the benefit of the capitalistic coalition of the West that the northern front attained its great political importance. The representatives of the Great Powers moved from Moscow to Vologda, and started a diplomatic campaign against the Soviet Government. After Comrade Radek’s mission to Vologda the significance of the northern front became grave from a strategical viewpoint also. The representatives of the Allies left their headquarters and moved to Archangel where they began, openly, their hostile policy against the Soviets.

The strategical plan of the Allies was as follows: An uprising of the Czecho-Slovaks was to begin along the Volga aiming its attack at the political centers of Russia; while in the east a permanent front had to be created, gradually moving its right flank towards the northern front in order to come into contact with Anglo-French forces, which had already landed in Alexandrovak on the Murmansk peninsula in the spring of 1918, and had started their movement southward. The general situation in Russia favored this plan of campaign. In some provinces which separate the northern part of Russia from the central part, the agents of the capitalistic coalition succeeded in raising against the Soviet Government a considerable part of the population, thus making it easy for the invaders to accomplish their swift march upon Moscow with the principal aim of overthrowing the Soviet Government. At first, the Allies were very weak. There were no more than 8,000 men landed in Alexandrovsk and Archangel, but after their troops had appeared at these points, the reactionary element of the Russian people started to group themselves around the invaders, thus increasing their fighting strength. About August 1, the Allied Navy destroyed the battery of Mudink Island, which protected the entrance to the Northern Dvina, and approached Archangel, landing an army corps from transports. The Red Guards did all they could to arrest the penetration of the invaders. The stations nearest to the town, Isako-Gorka and Tundra, several times passed from one side to the other, but finally the Reds, outnumbered by the enemy, were forced to retire.

A number of ships, captured by the invaders in the Bay of Archangel, were quickly armed and directed along the North Dvina. But in the middle of August, 1918, the enemy suffered a considerable defeat, and was unable to continue his movement further south until relief arrived, fresh American contingents, with whose help the town of Shenkursk was captured. The cold weather of the north Russian autumn was very unfavorable to the invaders, and they could only move their troops about one-quarter of the way between the mouth of the Eiver Vaga and Kotlas. In the direction of Onega, [Not Lake Onega, but the town of Onega on the White Sea.] the enemy concentrated his forces south of the village of Sumskoye.

In November, the frost and deep snow almost entirely paralyzed the activity of the enemy. The initiative gradually drifted from the Allies, and the Reds began to attack the invaders at several points. In the middle of winter, the Soviet forces concentrated to the south of Shenkursk, and by means of a sudden and most vigorous attack, this town was captured, and the rich reserves of ammunition, arms, and food supplies brought here by the Allies in the hope of establishing a base for further operations in Shenkursk, fell into the hands of the Bolsheviki.

Only in spring did the enemy begin an offensive again, between Lakes Vygo and Sego, when they succeeded in capturing the town of Povenetz.

This movement was provoked by the Finns, whose bands raided Olonetz, and the British command intended to support the raiders. But as usual the Allies came to the aid of the Finns too late. The latter were completely defeated near Birviza and the movement of the Allies became useless. Unable to reach Petrozavowsk, they became almost passive, and undertook some maneuvers in the region of Lake Onega and along the Murmansk railway. In the summer of 1919, the Reds won an important victory at Onega, and undertook a successful offensive up along the North Dvina—above the mouth of the Vega.

It became quite clear that the campaign of the Allies was lost. The Russian “volunteers” deserted in great numbers to the Bolsheviki, and there was neither unity among the Allied forces nor belief in their leaders. Some mutinies took place, and disorganization of the Allied contingent began, the best sign of the approaching end of this adventure.

In spite of the lack of good roads and the very severe climate of this part of Russia, the Red detachments, with the aid of the local Russian population, overpowered all obstacles, and established contact with one another in order to act in full harmony. We must not neglect the fact that this campaign was carried through during the first part of 1919, when the Military Commissariat was busy organizing the first body of the Red Army, and therefore proper support could not be given to the army engaged with the invaders on the northern front.

The Americans were the first who realized the uselessness of the expedition, and, tiring of the frivolous policy of the British command to which they had submitted, they left the battle front as early as June, and were sent back to their country. Finally, the British Government decided to evacuate Archangel, thus leaving the fragments of the White Russian troops and Northern Russian Government to their own fate.

The beginning of 1920 found the northern front completely liquidated, and Archangel, as well as the Murmansk peninsula, was gradually reoccupied by the Red Army without any serious resistance by counter-revolutionary forces.

It must be mentioned that the Red flotilla played a great part during this campaign, and the British naval forces suffered badly, thanks to the activity of the improvised Red Navy during the navigable periods. The task of the Northern Red Army was clear and simple,—to clear our North, and it was brilliantly accomplished in spite of all efforts of the Allies to prevent it.

The Eastern Front

“The Eastern front represented a very important, and, at certain periods, one of the most decisive fronts of the Soviet Republic,” declared Comrade Trotsky in his report read at the Seventh All-Russian Congress of Soviets in Moscow. By means of the Eastern front the Russian counter-revolutionary army, later led by Kolchak was to cut off the Soviet Republic from fertile and wealthy Siberia, from the industrial districts of the Urals, and from Turkestan cotton supplies. Here, as in South Russia, the economic conditions were of such great importance for the Soviet Republic that strategy considered its main problem the immediate reconquest of the trans- Volga region, the Urals, and all of Siberia. After a long and annoying struggle with the Czecho-Slovaks and unorganized bands of counter-revolutionaries united with them, the Red Command started to concentrate its forces in order to begin a serious campaign for the liberation of Siberia from foreign invaders. In the beginning of November, 1918, the Eastern front extended beyond the Volga along the line from Nizhni-Turiusk, Kungur, Sarapul, Bugulma, Buguruslan, Buzuiuk, and Novji-Uzen. The Red Army began its offensive in three directions with Orenburg, Ufa, and Sarapul as its objectives. Throughout the winter military operations were in full swing, and at the end of April, 1919, the line of the Eed Eastern front extended about sixty versts east of Ufa and seventy-five versts east of Orenburg, Uralsk, Alexandrovgai, and Guriev.

At the beginning of March, 1919, reinforced by fresh reserves, Kolchak directed his counter-offensive on Kazan, Simbirsk, and Samara, and in the middle of April his army attained the zenith of its success.

The situation of the Red Army became very serious. In the Southern part of Russia, Denikin inspired great anxiety, and the operations against the southern invader, though successfully carried out, were not yet really decisive in character, and forced the Red Command to be in full readiness to meet a coming serious offensive on the Southern front. Nevertheless it was first necessary to finish with Kolchak, while remaining temporarily on the defensive in South Russia. Therefore, almost all reserves were ordered to the East.

At first, the Kolchak army resisted with an extraordinary stubbornness, but when its demarcation line was seriously menaced, it was forced to fall back to Bugulma and Buzuluk, after which all the Kolchak forces began their retreat eastward. During May, 1919, the Reds had to fight for the possession of the outskirts of the Ural Mountains, finally forced the Ural passes and entered the plain of Siberia. Simultaneously, the workers and peasants of Siberia started their “partizan” campaign in the rear of the Kolchak forces, which, as we know, ended so disastrously for the latter. At the end of August the Soviet forces crossed the Tobol and pressed the enemy towards Ishim, but early the next month the counteroffensive of Kolchak forced the Reds to fall back as far west as Tobolsk. The counter-stroke of the weakened counter-revolutionary army was not, and could not be, strong enough to gain the initiative for a considerable length of time. After a series of serious tactical defeats, Kolchak not only lost the initiative but was completely beaten, suffering a strategical defeat which ended in the occupation of his political and strategical center, Omsk, and followed by a most energetic pursuit of the remnants of his beaten army.

This practically put an end to the campaign in Siberia, from a strategical point of view, and all further uprisings and military operations in East Siberia are more of a local political character.

According to the official report of the present commander-in-Chief of the Red Army, Comrade Kamenev, who is responsible for the whole Siberian campaign against Kolchak, there were fourteen fronts of the Siberian counter-revolution.

The Japanese and American troops landed at Vladivostok in August, 1918, and together with the local reactionaries began a campaign against the Soviets in the Amur district, gradually moving westward towards Lake Baikal, and to the north along the Amur Railway line. A regular uprising of Russian population attained very serious proportions. Armed bands of insurgents operated throughout the country, and inflicted heavy losses on the Japanese and Americans- The local administration of the Kolchak “government,” in spite of its drastic measures against the insurgents, became fruitless. The famous ataman and bandit, Semionov, his colleague, Kalmikov, recently assassinated in Manchuria, General Larionov, Baron Tungern-Sternberg, Colonel Silinski, and many others, in spite of all their efforts, were unable to stop the elementary movement of the Russian masses against intervention. Here and there, throughout all of eastern Siberia, fierce sanguinary fighting raged between the insurgents and the Allied troops on the one hand, and between the former and Russian generals on the other. Finally such confusion arose that nobody knew whom he was fighting in reality, and such conditions existed from Chita to the Pacific. The occupation of Vladivostok by the Japanese, after the evacuation of Siberia by the Americans, as well as the further conflicts of Japan with the new Government of the Far East, the friction between Generals Semionov, Horvat, Kalmikov and others, and the streams of blood of the peaceful population, all this was the result of the baseless, stupid, and criminal armed intervention of the Allies.

During 1919 alone, according to official information, the number of victims in towns and villages in that part of Siberia was estimated at about 80,000 civilians killed, besides the casualties in the rank and file of the different Russian forces, Reds as well as Whites. At the present time, the Far Eastern Government, with its headquarters in Vladivostok, is practically in control of the Maritime and Amur districts, which are still occupied by Japan. The Red forces, meanwhile, are concentrated partly in Transbaikalia and in the province of Amur, ready to complete their strategical task in the Far East as soon as the situation in European Russia is settled.

The Turkestan Front

The Turkestan Front was separated from the Eastern Front, and became independent after Kolchak’s southern army was entirely defeated in the Orenburg district, and Orenburg was captured by the Red Army. Thus 45,000 Kolchak soldiers were taken prisoner, and an enormous quantity of booty fell into the hands of the Soviet troops. The final union of the troops on the Turkestan Front, (that is, of that part of our front which is facing Turkestan) with those troops which were actually stationed in that region, came about in the middle of September, 1919, in the district of Station Emba on the Orenburg-Tashkent Railway which thereafter became a most important means of communication between Moscow and Central Asia.

The victory of the Red Army opened up inexhaustible possibilities for the Soviets. The Soviet Government was established throughout all Russian Turkestan. A result of this victory was the establishment of friendly relations with Afghanistan and the Extraordinary Embassy of the Amir arrived in Moscow. Strategically, Soviet Russia has succeeded in organizing with Turkestan a united army, and special “partisan” detachments, subjected to one single command, were formed at once. Early in 1920, the result of this victory could already be seen. The British movement from Persia into Turkestan and through Afghanistan now became an impossibility. The revolution in Persia and the Anglo-Afghan War put an end to British indifference as to the influence of the Soviets in Asia, where the Russian proletariat put themselves on a solid footing. The occupation by the Russians of the port of Enzeli, and their march on Teheran, as well as the successful operation of the Turkestan troops in the rear of the Denikin army, were strategical results of the Russian successes in that part of the Republic. The Red Navy took a very important part in the operations on that front, and succeeded in destroying the British naval forces on the Caspian Sea, thus opening the route for the Red Army in Transcaspia, Transcaucasia, and Persia. The famous oil industry of the Baku region, already captured by the British, again came into the hands of the Soviets. A quick concentration of the Soviet Army on the new front alarmed the British. The possibility for Soviet Russia of cooperation with Turkey and the Caucasian republics, became a reality, and the possible menace to India confronted Great Britain more seriously than ever before. Finally, the British Government showed great care in regard to her attitude of further support for the Russian White General, and became less aggressive against the Soviets. Only the success of Red strategy in Central Asia forced the British diplomats to begin negotiations with Moscow, and brought the Russian Trade Commission to London to negotiate commercial relations. How far events would have developed on the Turkestan and Caucasian fronts is difficult to forecast now, but I can state that here the Soviet Army attained a complete victory, and holds so strong a position, that only in a real war with the western coalition would it perhaps yield all it has succeeded in winning.

The West and East Caucasian fronts as well as the Transcaspian front were also of great importance; here the Soviet Army was able to check the British intrigues directed against Georgia, Persia, and the Azerbaijan Republics, and it is only owing to the lack of space that we include the review of these fronts under the general title: “The Turkestan Front.”

The Western Front

At the end of 1918, after the collapse of German militarism, which was brought upon Germany not only by the military force of Allied imperialism, but from within by the masses of the German workers and peasants, the yoke of the Brest-Litovsk Treaty, imposed upon Soviet Russia, was automatically destroyed. The Red Army on the Western front in those days included Esthonian, Lithuanian, Lettish and White Russian detachments, which took the offensive, and in March, 1918, a great part of Esthonia and a greater part of Latvia, Lithuania, and White Russia established Soviets. These countries formed their own armies. At this moment, however, the western capitalistic coalition succeeded in supporting the bourgeoisie of the newly formed republics to such an extent that they were able in April to attack the Red forces, defeat them, and start an offensive against the Soviet Republic. This coincided with Kolchak’s offensive in the East, and the sharp struggle in the South, making it impossible for the Red Army to resist the advance of the Poles, Letts, Lithuanians, and Eethonians, backed by the Allies. Vilna and Riga were captured by the aggressors, and only in September, the retreat of the Red Army along the whole line on the Western Dvina, from Polotsk to Dvina, and later on, along the line of Berezina to Pripet, was arrested. Henceforth the Red front, extending from Pskov to the South, became a permanent line for the concentration of the Red Army. Twice, on this front, the Russian Soviet forces were attacked by the so-called Yudenich army which cooperated with the armies of the small bourgeois republics of the Baltic region. There the question concerned Petrograd and its fate, over which the bourgeoisie of the world gambled. But as our readers are aware, Yudenich’s adventure, thanks to the self-sacrifice of the Red Army, and thanks to the superhuman effort of the Red Baltic Navy, became a complete failure. Petrograd was in great danger, not only because of attack from the west, but because of the very serious intention of the Finnish bourgeoisie to support the plot of the Allies. The situation was very grave, moreover, because at the time the Soviet Army was fighting for the fate of Petrograd on the Pulkov Heights, the Finnish White Guards subjected the Red troops to curtain-fire not only from machine guns, but from cannons, and bombed Soviet territory with dynamite. According to the report of Comrade Trotsky to the Congress of Soviets of December 7, 1919, the Soviet Army in those days was “strong enough to make a counter-offensive.” “But,” says Comrade Trotsky, “we gave orders to the local command saying, “no notice is to be taken of provocation; but should Finland interfere in spite of this, should she cross the border, should she make an attempt to strike at Petrograd, you are not to limit yourselves to mere resistance, but you are to enter on a counter-offensive, and follow it out to the end.” And the Finnish bourgeoisie understood what it meant.

The end of 1919 found the Polish army in Lithuania, White Russia, in the greater part of Ukraine, and even in Great Russia. There was no peace between Moscow and Poland, but there were no serious hostilities either. Soviet diplomacy basing its policy on the principles of self-determination of nations did not fix a definite frontier-line between Poland and the Soviet Republic. The Polish Front was not considered strategically important, being the weakest of all the Red fronts, and Moscow made every effort to conclude peace with the Polish Government.

On April 18, 1919, Comrade Chicherin approached the Polish Government with an offer to negotiate peace, but in answer to this a Polish detachment disguised in Red uniform, under Red banner, took Vilna from the Lithuanians.

On December 22, 1919, a formal note of Chicherin with an offer to negotiate peace was transmitted by radio to Poland. There was no reply.

On January 28, 1920, a formal note was communicated to the Polish Government and only on March 27, two months later, did Patek, the Polish Foreign Minister, answer more or less favorably. But difficulties arose because of the insistence of the Polish diplomats that the peace negotiations should take place at Borisov, a Russian town on the Berezina, just captured by the Poles, and situated just in the middle of the battle front Russian strategy could not permit this, especially when the Polish diplomacy refused to fix an armistice and stop hostilities along the whole front.

On April 23, in its note to the whole world, the Russian Government declared that it was ready to meet the Polish delegates in any country, and in any town that was not on the front zone. But the Polish Government did not desire peace. The negotiations, however, were important to enable it to camouflage the concentration of the Polish army and in this it succeeded in full.

Early in March, 1920, the Poles suddenly attacked the weak Russian forces along the whole front and took Mozir, Kulenkovichi, Ovruch and Eezhitsa, and on April 23, began a vigorous offensive on the Volhynian-Kiev front, captured Zhitomir and Zhmerinka and directed the main bulk of their army on Kiev. The famous Ukrainian bandit, Petlura, became an ally of the Poles. In exchange for all Eastern Galicia which he had given up to Poland, he was to be established as a dictator over Ukraine, by force of the Polish arms, thus subjecting ninety-nine per cent of the Ukrainians to the Polish yoke.

The rest is well known. The Polish army crossed the Berezina and Dnieper, and began invading Russia with Moscow as its strategical objective. Fifty miles east of Kiev, the Poles met the bulk of the Red Army, were entirely defeated, and began a hasty retreat, pursued by the cavalry of Comrade Budenny and the advance guard of the Northern army of Comrade Tukharevsky. This pursuit was of great strategical significance, because its duration was more than a month, and the Polish held army was practically annihilated and henceforth deprived of the possibility of repeating an invasion of Russia, and consequently reaching Moscow, in order to overthrow the Soviet Government.

The failure of the Soviet army in their attack on Warsaw and the resulting tactical defeat of the pursuers did not affect the strategical situation of the Soviet Army, which was reinforced by fresh reserves and is gradually recovering its lost initiative, thus supporting the Soviet diplomacy and establishing a long desired peace with the last hostile neighbor to the West. Strategically even a short armistice with the Poles was of great importance for the Soviet army, not in order to reinforce its western front, but rather to accomplish some regroupments to support the Southern Red Army, which, thanks to the Polish campaign was left to its own fate in fighting the hordes of Baron Wrangel, the only active enemy of Soviet Russia left now in Europe.

The Ukrainian front, being closely connected with the Polish front, is losing its strategical importance since the peace relations between Poland and Soviet Russia are almost established.

The Southern and Ukrainian Fronts

I have always considered the South Russian front as a most decisive and most important front for the Red strategy. The war in the south is the oldest of the civil wars. It was begun by cossack forces before the Czecho-Slovaks and Kolchak were created as the “champions of the Constituent Assembly.” The cradle of the counter-revolution was the Don. Active aid from the working element of the cossack population, together with the Red detachments of Comrade Antonov, caused the liquidation of the power of the White Russian generals. Kaledin shot himself and Kornilov was forced to find a refuge in the Kalmuk steppes; finally Soviets were established throughout the Don. During the summer of 1918 the situation in South Russia was aggravated by the appearance of General Krassnov with his cossacks, who aimed to capture the rich Donets industrial district. He was backed by the Germans, who occupied Ukraine. Early in 1919, the Don Cossacks were seriously defeated by the Red Army, but the reaction in the Kuban and amongst the Don Cossacks gave an opportunity to General Denikin, the successor of the departed Kornilov, to form a strong army in the Caucasus and Kuban.

In the middle of January, 1919, the Southern front is occupied by the so-called “volunteer army”, under the supreme command of Denikin, and the Don Cossacks are forming thirty-seven cavalry and infantry divisions—to cooperate with him.

From the Don Cossack region to Kamishin, on the Volga and the stanitza (village) of Nizhni Chirskaia, this front enabled the enemy to cut off Soviet Russia from coal, and oil supplies and from her richest agricultural area. Therefore the strategical problem of the Soviet Revolutionary Field Staff was to recapture the Donets coal district and to open the way to the Caucasus oil region.

In the middle of January, 1919, the Red Army concentrated its forces and started an offensive on a wide front: Ostrogorsk, Borisoglebsk, Povarino, Yelan, Tsaritsin, and Sarepta. In the middle of February the Southern Red Army forced the Don and the beginning of May found the Soviet troops eighty versts northwest of Taganrog and 125 versts to the north and forty versts to the east of Rostov. Further to the southeast a line of fifty versts was occupied by the Reds, south of the river Manich,—and the advanced troops attained the upper Kuma and approached the middle Terek. The strategical aim of the Red Field Staff thus was accomplished in three months, and the further operations were not undertaken because of the developing battles with Kolchak and on other fronts.

This interruption of hostilities was sufficient to enable Denikin to gain time and to reorganize his army. He then formed a strong body of cavalry and started a vigorous offensive from the Manich in the direction of Tsaritsin, and on May 20, by means of British tanks and poison gas, he broke through the Red front in the region of Yuzevka. The mutiny amongst the Don Cossacks against the Soviets in the middle of March, in the rear of the Red front, helped Denikin’s advance and forced the Red Field Staff to order a general retreat, protected by rear-guard actions.

The offensive of the enemy was directed northward, towards Bolashov and Voronezh, as well as in a northwesterly direction, on Kharkov, Poltava, Yekaterinoslav and Kiev. The Red Army stopped its retreat, and then began to counter-attack the invaders, the main front line passing through Nikolaiev, Yelizavetgrad, Bobrinskaia, Romni, Obaian, Korotokmak, Liski, Povorino, thence to the Volga.

The counter-offensive of the Reds in the middle of August had as its objective to occupy the Kharkov region as well as the lower basin of Don. In twelve days the Soviet troops succeeded in capturing Volniki, Kupiansk, Volchansk and approached to sixty versts from Kharkov, speedily moving also toward the middle Volga. By means of a strong cavalry counter-attack in the Kursk and Novokhopersk direction, the enemy not only stopped the advance of the Red Army, but succeeded in breaking through the Red front in the direction of Novokhopersk, and the cavalry of Mamontov and Shkuro penetrated far to the rear of the Soviet field army and raided Tambov, Kozlov, Yelets, and Voronezh.

Finally, the new retreat of the Red Army brought the Denikin bands as far north as Orel, but here, north of that town, in the Tula direction, he was met by fresh Soviet reserves. A decisive battle took place, and after a series of tactical reverses, Denikin received a final strategical blow near Kharkov, and his panic stricken forces were dispersed in complete disorder and energetically pursued and annihilated by the Red cavalry.

Only in the Crimean peninsula, under the protection of the Allied navy, a small part of the Denikin forces, under Baron Wrangel, one of Denikin’s generals, were reorganized, with the help of the Entente, as a new counter-revolutionary force, which was to cooperate with the Poles. The general aim of Wrangel’s strategy is practically the same as that of Denikin, but the existing political and strategical circumstances, as well as his resources of man-power and supply are much inferior to those of Denikin.

The third year of the titanic struggle of the Russian proletariat has ended with the triumph of the Revolution.

Soviet Russia began in the summer of 1919, published by the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia and replaced The Weekly Bulletin of the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia. In lieu of an Embassy the Russian Soviet Government Bureau was the official voice of the Soviets in the US. Soviet Russia was published as the official organ of the RSGB until February 1922 when Soviet Russia became to the official organ of The Friends of Soviet Russia, becoming Soviet Russia Pictorial in 1923. There is no better US-published source for information on the Soviet state at this time, and includes official statements, articles by prominent Bolsheviks, data on the Soviet economy, weekly reports on the wars for survival the Soviets were engaged in, as well as efforts to in the US to lift the blockade and begin trade with the emerging Soviet Union.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/srp/v3n19-nov-06-1920-soviet-russia.pdf