An extraordinary article on the underground work of Japanese Communists in the Imperial Army in the early 1930s, including in the occupation of Manchuria. Through passages from the Party’s newspapers ‘Sekki’ and its illegal newspaper ‘Soldier’s Friend’ the brave, incredibly dangerous work of militants, many of them martyred, is told.

‘Activity of the Communist Party of Japan in the Imperial Army’ by Katsuo Tanagi from Communist International. Vol. 11 No. 14. July 20, 1934.

A tall wooden fence stretches along the street over a whole block. Painted a dull blackish-gray color it reminds one of a prison wall, which cuts off part of the street, festive with green vegetation, the sun, the shop windows, where bright textures show off their colors, where fruit and vegetables form a palette of paints, and where bright parasols spread their fancy wings.

A massive gate is in the center. Two striped sentry-boxes stand near the gate. Two khaki-clad sentries stand at attention under the scorching rays of the sun. From morning till night, broken shots are heard- there, and a cacophony of signal horns. Here are the barracks of the N. regiment stationed in Tokyo. Here, as in thousands of similar other barracks scattered all over Japan, are locked in the best elements of ·the youth of the nation. Cannon fodder is being prepared out of them, for the war which is now going on, and for the war which is to come.

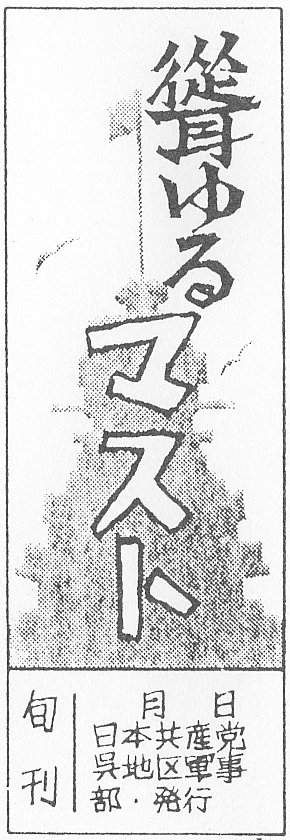

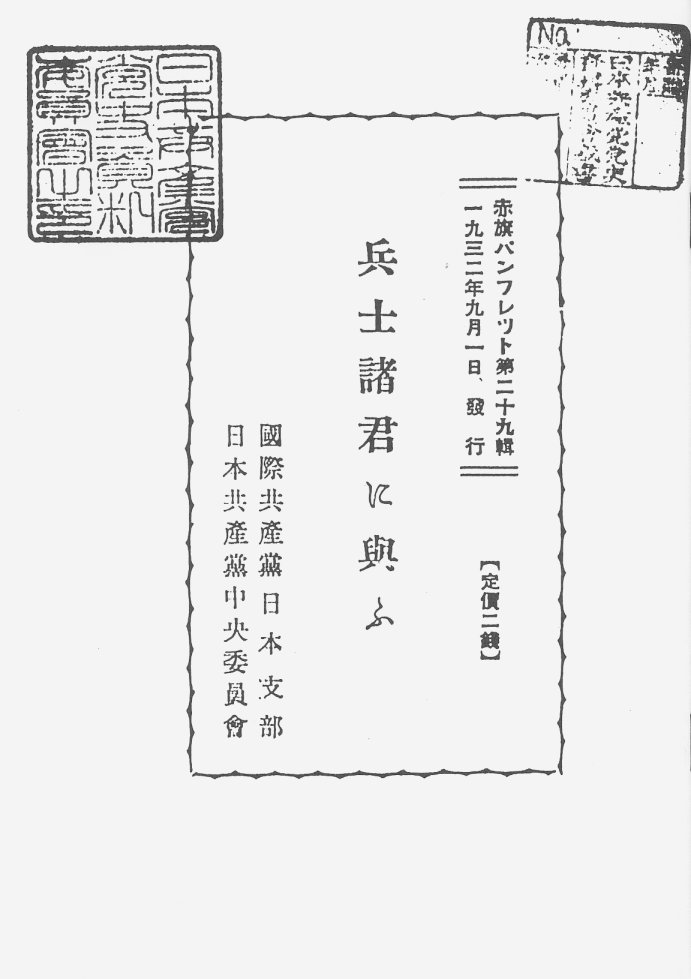

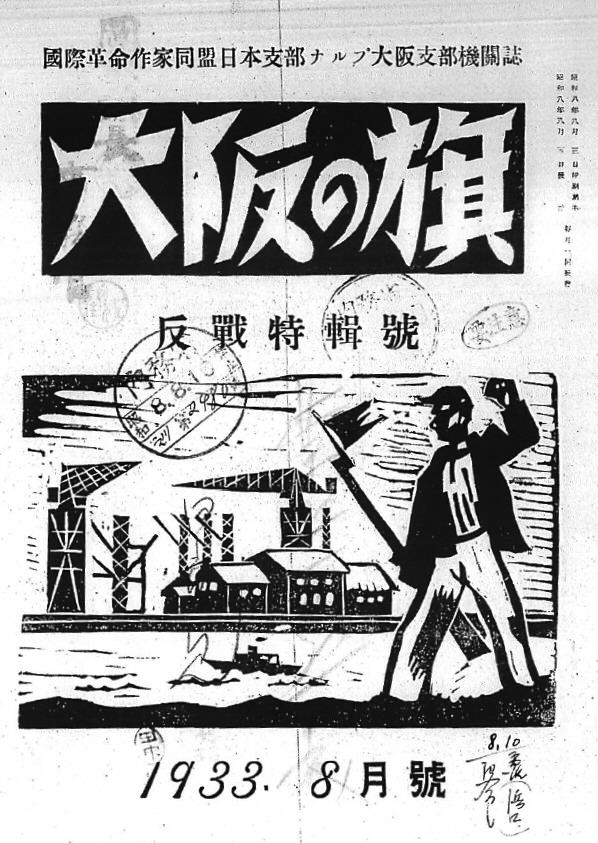

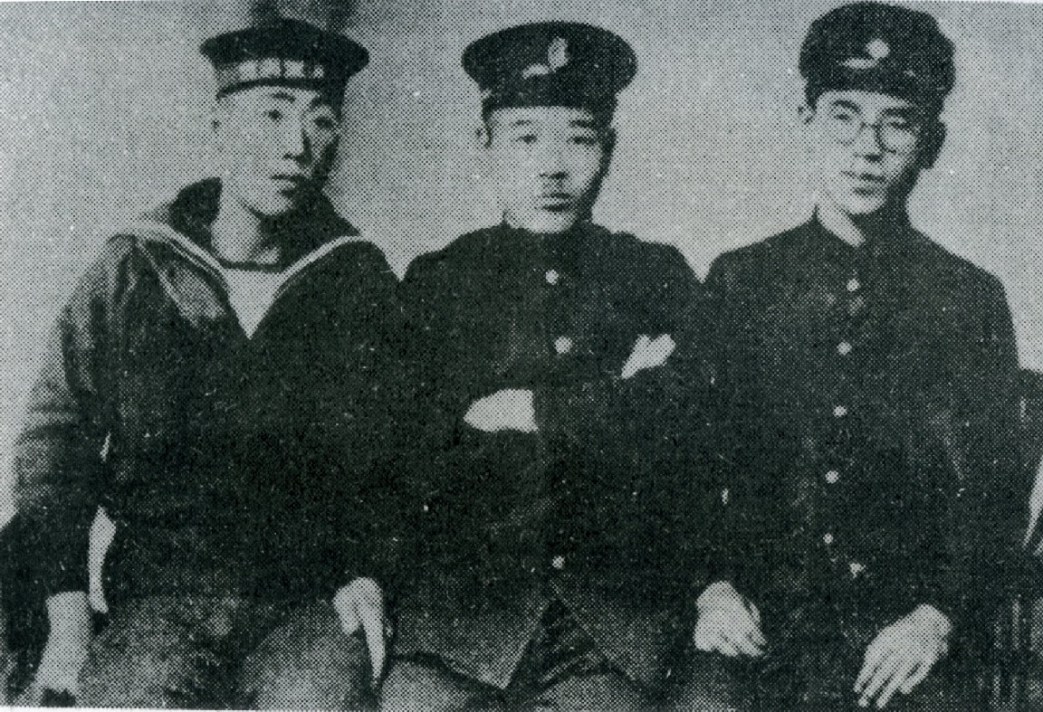

From the very first days of the war in China the Communist Party of Japan placed its best members in the barracks, on the men-of-war, and at the front. In spite of all obstacles the Party press, and Party leaflets, penetrated into the ranks of the “Emperor’s army”, bound the workers and peasants clad in khaki to their brothers in the factories and villages with thousands of powerful threads. Since the Manchurian events, the central organ of the Party, the Sekki, has become a real anti-war, Bolshevik newspaper. The paper set up a special section for propaganda in the army and navy, which contains letters from soldiers and sailors of the expeditionary units and from garrisons in the rear. In September, 1932, the Soldier’s Friend (Neisi no tomo) appeared in the army. The Party began to issue a special monthly paper for the masses of soldiers. In October, the mass arrests of Communists disrupted the publication of the paper for a time, but it began to appear once more in the beginning of March, 1933. A naval newspaper, The Lofty Mast, began to appear in the military port of Kurs. Local papers were published by Communists in the barracks, men-of-war and ports.

A recruit ceases to be a human being as soon as the gates of the barracks are locked behind him. He becomes a soldier. Day in and day out, until his unit is sent to the front, he will march on the parade ground until he is dizzy, and to the accompaniment of the howling of non-commissioned officers, he will be taught to shoot, to stab, and to suffocate while wearing a mask during training. Military drill, cruelty and promotion will make an obedient killing automaton out of him.

The Soldier’s Friend correctly approaches the soldier, who is tormented by his drill, by dealing first and foremost with the things that agitate him. In publishing letters from soldiers and sailors in different units, the newspaper shows how hard is the life of the soldier in the army and in the navy. By arousing a protest from the masses against the barbaric methods employed in military training, against the arbitrariness of the officers, the newspaper shows the way to struggle, namely, by creating soldier’s committees.

“…Lately, in connection with the preparations for the regimental shooting contest, we are daily in our company having strenuous training and shooting matches. We are told that if the company shoots successfully, we will receive a present from the Emperor. This is the usual maneuver of the rascals, to evoke competition between us. This is how they force us to train ourselves in the art of the murdering of men.

“On June 20, while training, 15 soldiers showed very bad marksmanship. As punishment they were ordered to run at full speed in full equipment from Toyamagahar to the barracks. Tired from the day’s training, one of the recruits fainted during the race in the street of Sendshey. Half an hour later he was found lying there by the comrades who picked him up. Another of these soldiers lost consciousness and dropped near Seimon. He regained consciousness only in the morning. This refers not only to the soldiers who suffered in this particular case. Similarly cruel barbaric training is applied to all soldiers. Therefore this case is one that affects us all. Many of us are discontented, but we keep silent. After this case, we have begun to feel the necessity of uniting for the purpose of jointly presenting our demands to the officers and the noncommissioned officers. We shall immediately organize a soldiers’ committee!

“Soldiers of X Company, Y regiment.” (Soldier’s Friend, No. 2, March IO, 1933).

On board the men-of-war, the sailors are tormented, in addition to drilling, by the drudgery of “keeping the vessel in order”. The Soldier’s Friend raises this question before the masses of sailors in the following letter:

“…I believe that such conditions are to be found not only on board our ship, but on the other ships as well. We don’t see the light of day because of the work we have to do. This work does not last a day or two; it lasts for months at a stretch, so that the weaker chaps break down. We clean the vessel from rust, and inhale the smell, and paint the vessel in such places where the air is so foul tint the candles go out. And after working in one spot for a few hours, we all express our discontent. The question is asked, ‘and does the Emperor know how hard our work is?’ We are only the children of His Majesty when we are fed with bullets. But it is no concern of his when we starve. We are against war, which destroys workers and peasants! We demand sanitary equipment on board ship! The money spent for the war should be given for unemployment dole! Such is our unanimous opinion. I believe that our brothers on board other ships are just as dissatisfied. If so, then it’s no use being silent! We must unite our forces and act jointly. Only then will we succeed in getting our demands satisfied and improve the life of our brothers.”

The Japanese militarists devote a great deal of attention to the ideological training of the soldier. The line followed by the barrack “political schooling”, which takes up a considerable part of the soldiers’ time, is to make a devoted servant of the Emperor and fatherland of the worker or peasant lad, to set him against “domestic and foreign enemies”. The soldiers are told over and over again about the divine origin of the dynasty, and about the invincibility of their army and the Emperor. The ideal of loyal faithfulness and self-sacrifice is hammered into them, by quoting many examples from history and from the biographies of various generals. Particular attention is devoted to setting the soldiers against the U.S.S.R. and the Communists. In the very heat of the military activity in Manchuria, there were cases of military games being organized, staging the seizure of Soviet trenches.

The Party is developing a fierce struggle against the monarchist and chauvinist training of the masses of soldiers and sailors. The Party press is organically imbued with the struggle against the monarchy. Both the Soldier’s Friend and the Sekki show many excellent examples of Bolshevik agitation among the soldier masses against the monarchy. Thus we read in the Soldier’s Friend:

“…As we are aware, the essence of the military training in the Japanese army is the blind, forcible hammering in of monarchist ideas into the heads of the soldiers.

“We are forced to read and to copy ‘the August Decree to the Soldiers’, which reads: ‘We, the Emperor, are your Marshal. You are our faithful servants. You must profoundly receive us, your head,’ and so forth. But if all this is true, that the Emperor is our Marshal, and we are his faithful servants, then how is it that the following events can happen? How did the Monarchist government, the militarists, and the police behave, when the street car workers, who are our brothers, recently began a struggle against dismissals, against wage cuts and persecution? What did they do when our fathers and brothers in the villages in the prefectures of Niigate, Yamenasi, Mie, Seitams, Aomori, and Nokkaido rose against the hated landlords for rice, and for land? The Emperor’s government is a government which ruthlessly suppresses the struggle of our fathers and brothers against unemployment, exploitation and want. And when we, workers and peasants, clad in military uniform, are told that we must be the first servants of the Emperor, they deceive us! …”

In exposing the extraordinary parliamentary session of 1932, as a session for the speeding up of war, the Soldier’s Friend skillfully makes use of the patriotic hullabaloos raised by the bourgeois press in connection with the news that the court intended to come to the aid of the people, by donating 4,800,000 yen in the course of five years. In this regard the Soldier’s Friend stated:

“…4,800,000 yen appears to be rather a big sum. But let us examine what part of the total funds at the disposal of the Emperor’s court this sum represents. This sum is to be spread over five years, which makes it 960,000 yen per annum, whereas the yearly income of the court is 34,500,000 yen. Of this sum, 4,500,000 yen comes out of our taxes. The income from bonds and lands owned by the court amounts to 30,000,000 yen. Thus, even if the Emperor gives 4,800,000 yen, it will be merely one-thirty-sixth of his yearly income. He will give one yen out of every 36 yens of his yearly income. If you divide these 960,000 yen among the 90,000,000 of Japan’s population, only 1.1 yen falls to the share of each person. Such a miserable pittance will hardly help anybody. The fraud is quite obvious. The Emperor gives it because he is afraid of the sharpening of the struggle of the workers and peasants inside the country. In Osaka a movement is already developing for the distribution of this money not in five years, but at once and immediately.”

The soldier is locked up in the barracks, or hurried to the front, and has almost no contact with his family and his friends. The army is mostly composed of peasants. It is usual for recruits to be sent from one locality to another, farther removed from their home. Contact by post remains. But it is rather difficult for the soldiers to keep up a correspondence on the beggarly pay they receive. They frequently haven’t enough for a postage stamp. Furthermore, the officers who take care of the proper moral and political welfare of their units subject both the soldier’s letter home, and the letters he receives from home, to a rigid censorship, frequently confiscating them.

The Soldier’s Friend tells the masses of soldier the truth about the sufferings and starvation of the soldiers’ families, who are without their bread-winners. It cites authentic facts of the wanton ruination of the homesteads, and suicides of the soldiers’ relatives, quoting their names and the names of the villages. It gives the soldiers an exposure of the true essence of the extraordinary parliamentary session of 1932, so much advertised by the bourgeois press as a “Session for the Salvation of the People”, and claims that the building works undertaken to help the village will in reality bring no actual help to the peasantry. This is what the paper says:

“At first the Government announced that 340,00,000 yen would be assigned under the estimate for the ‘relief of the people’. However, ‘owing to financial difficulties’ the estimate was put down almost by half, namely to 160,000,000 yen. The estimate of each ministry is the preparation for a big war under cover of relief. According to this ‘relief’ estimate, 43,000,000 yen are allotted for the improvement of arms, ammunitions and equipment for the army. 43,000,000 yen are assigned for the building and repair of men-of-war. 10,000,000 yen are assigned to the Ministry of Communications for the opening of an airline between Hokkaido and Formosa. 44,000,000 yen are allotted to the Ministry for Home Affairs for the laying of a special telephone system, etc., etc. All this is called ‘relief’, but it is as clear as daylight that it is an estimate for war preparations.”

The government is advertising building works for the relief of the peasantry, as the basic work to help the population. It says that if one-half of the 75,000,000 yen allotted for this work, i.e., 37,500,000, be spent as wages to the peasants employed on it, then 43,700 peasants will thus be helped. This is an outright lie! Only 315,000 people will be able to get employment. Compare this figure with the 30,000,000 population of starving peasants. Such in reality are these shameless fraudulent figures of ‘relief’!

The Sekki writes systematically about the disastrous position of the peasants, about the way tenants are driven from the land, about the forcible extortion of taxes, about the confiscation of their crops and the sale of farms by auction in order to extort debts and taxes. The paper explains that the 2.2 billion war budget, the war loans, the driving of the workers in the peasant families to the front doom the peasants to ever more weighty disasters. The paper demands that all tax indebtedness be annulled, that the poor and middle peasants be exempted from taxes, that all the taxes should be extracted from the landlords and the kulaks. The paper demands that the units be recalled from the front, and that the money spent for the war be devoted to assisting the peasants and the unemployed.

The Communists who work in the village in the peasant unions use the opportunity provided cases of oppression by the landlords of the families of peasants recruited into the army, and cases of land confiscation, etc., to link up the struggle of the tenants with the anti-war struggle. In a number of regions the revolutionary peasant union has succeeded in organizing its anti-war activity so efficiently that the authorities and the gendarmerie have been forced to restrain the attacks of the landlords on the soldiers’ families.

The Communist Party of Japan exposes the class nature of the “Emperor’s army”, and is fighting for the establishment of an active link between the workers and the soldiers.

From the very first days of the war the Party put forward the following demands: to pay wages in full to workers taken into the army; to include the period of military service in the uninterrupted period of industrial service; (*It is a practice in Japanese factories that a lengthy period of industrial employment entitles the workers to a pension “for having worked a certain period of years”, and larger benefits in case of dismissal, etc.) to immediately supply demobilized soldiers with employment on the same terms as before the mobilization; to provide for the families of the soldiers, etc.

These demands of the soldiers were immediately caught up by the masses in the factories, etc. The workers began to put them forward in strikes and conflicts. These demands were particularly widespread at the very height of the war operations in Manchuria and near Shanghai, when many workers were taken into the army from the works and factories. The struggle of the workers striking for the soldiers’ interests was one of the forms of rendering the economic struggle political and of interlinking it with the anti-war struggle. On the other hand, the wave of these strikes exerted a great influence upon the army. At the time when the workers of the Tokyo subway went on strike (March, 1932), and set forth the soldiers’ demands, under the leadership of the Communists, the soldiers at the front followed the heroic strike and discussed it. It excited a live response among the masses of soldiers. In Tokyo itself, a soldier, who formerly worked in the subway, deserted from the barracks to help the strikers. He came to the strike committee and the workers had great difficulty in persuading him to return to his unit, and not to ruin himself in vain. This case of desertion was taken into consideration in military circles. Both the military and the gendarmerie authorities came out with assurances that they would themselves take care that the employers would not infringe on the interests of the “heroes, fighting at the front”.

At the beginning of 1933, the fascist trade unions and the reactionary organizations in the factories started an intense campaign for levies and donations for the “defense of the country”, for the construction of tanks and “Patriot” airplanes at the expense of the workers. The Party organized a counter-campaign against war and fascism. In the factories the Communists organized all kinds of workers’ meetings, talks, “tea parties”, etc. They secured the adoption of proposals to disrupt and boycott the collections, about the raising of wages, about stopping the intensification of labor as a result of war orders. And along with this, they proposed that the funds already collected should be placed under the control of the workers and should be handed over for the relief of the soldiers’ families, and to the peasants of the northeastern provinces, who had suffered from the flood, and to the unemployed. Thus, the Party once more introduced the “demands of the soldiers” into the struggle of the workers.

Without confining itself to this, the Party put forward the demand for immediate State assistance at the expense of the war budget, to those in need from the flood. It demanded that the soldiers stationed in China, who were natives of the provinces affected by the catastrophe, should be sent back home; that the troops and men-of-war sent there to “maintain order” in connection with unrest among the peasants should be withdrawn. This activity of the Party inside the army found its reflection in the ferment that developed among the soldiers who were natives of the provinces affected by the flood.

In the summer of 1933, the Party waged an antiwar campaign in connection with the air-defense maneuvers in the Canton district. Among the slogans launched during the campaign there were again included slogans concerning the soldiers, such as: medical treatment and rest for the soldiers wounded when in maneuvers, payment of double wages after the maneuvers, relief to soldiers’ families at the expense of funds allotted for the maneuvers, compensations for the losses due to the damages caused to peasant fields, payment for military quarters in the villages, etc.

At the same time, the Sekki stressed that the struggle against the air maneuvers presented excellent opportunities for the organization of the united struggle of the workers, peasants and soldiers, and indicated to the Party organizations the forms for rapprochement between the masses and the soldiers, and the forms of joint struggle, such as, for instance, the organization of amusements for the soldiers at the bivouacs, the setting up of committees to estimate the losses caused by the maneuvers to the peasant fields-committees made up of workers, peasants and soldiers.

While struggling for the establishment of a bond between the workers and the army, both the Sekki and the Soldier’s Friend systematically gave publicity to the worsening of the conditions of the workers in the factories, etc., in connection with the war, and the struggle of the workers against this, stressing the necessity for joint struggle. This is how the Sekki described the conditions of the workers at the Nakedzime works, which was engaged on urgent war orders:

“Aviomotors are manufactured here. Only 20 per cent extra is allowed for work the whole night through. The workers are getting thinner. they have lost weight up to 1 kan.

“Last year we were producing from 14 to 15 motors a month, now we are making 50. The officers commissioned to the works speak about the necessity of increasing the monthly output of motors up to 100, for otherwise, they say, we will be unable to win the war. If we continue this way in the future, we will drop off our feet altogether.

“The departments are strictly separated from one another. Communications between the workers employed in the different departments is almost impossible. It is impossible to exchange a few words with your comrades. The ceilings in the department are made of glass, and a supervisor watches from above, who is doing the talking. Gendarmes are permanently present at the works. ‘Pinkertons’ are in abundance all over the place. We are watched as though we are in a prison.

“At night, the moment the supervisor goes out, the workers talk about their low wages, and their long working hours. In the machine section, the workers began to grasp that the more they worked, the more their piece-work rate was reduced, so they ceased to rush their work. General indignation prevails. The walls of the lavatories are covered with protests. As soon as they are whitewashed, fresh inscriptions make their appearance.” (Oct. 20, 1933.)

An excellent way of linking the workers with the army was the organization of meetings at the factories, etc., on the initiative of the Party, in connection with the homecoming of soldiers on furlough, or of demobilized soldiers who spoke at these meetings and spoke about the war or life at the front. In these cases the soldiers frequently proved to be the best agitators against the war. There were cases when the Communists transformed the parties, organized by the factory owners for the purpose of raising patriotic sentiments among the workers, parties in honor of the “heroes returned from the front”, into anti-war meetings.

“…At one Tokyo works,” stated a report in the Soldier’s Friend, “the management organized a gathering to hear stories about the war. Seventy workers were present. The tale was told by a soldier from the front. He spoke for about two hours about what the soldiers had to suffer at the front. Even there the officers wrapped themselves in several blankets, whereas the tired soldiers were unable to sleep at night, on account of the cold, for one blanket had to be shared by three men. The soldiers were not supplied with warm clothing, while they had to shoot from the knee, or lying in the snow in frosts of 40 degrees below zero (C.). The food was so bad that even pigs would not eat it. The chairman of this meeting finally got scared and closed the gathering. The audience was very much excited and carried a resolution against the war.” (March 13, 1933.)

The Party is popularizing the peace policy of the U.S.S.R. among the masses of soldiers and tells them what the Red Army is, how it differs from the Japanese “Emperor’s army”. For instance, we find in the Soldier’s Friend of March 10, 1933, a large article headed, “A Day in a Red Army barracks of the U.S.S.R.” The paper described this day, from reveille in the morning until “lights out” at night and related how the Red Army man masters military technique, how he improves his cultural standards, how he spends his leisure hours. The paper built its entire story on a contrast between the conditions prevailing in Soviet barracks and those in Japanese barracks. In a description of the political hour, devoted to the question of the possibility of the Japanese troops, who seized Manchuria, attacking the Soviet border, the newspaper inserted the following words into the mouth of a Red Army man:

“…”We will have to fight firmly against those who attack our Soviet Union, our workers’ and peasants’ State, whoever they may be. However, not all are alike in the Japanese army. The majority in that army are Japanese soldiers who do not know for whose sake they came to Manchuria, and what they are fighting for. But there is a real army, who forces these soldiers to fight. This is the Japanese capitalists, the landlords and the monarchist government. The Japanese soldiers, like ourselves, are children of the workers and of the peasants. There is no law that the children of the workers and of the peasants should kill each other. And this should be told to our Japanese comrades in the first place.

“Fifteen years ago we annihilated the barbaric power of tsarism, and of the landlords and capitalists, and established a workers’ and peasants’ power in Russia. For 15 years we have defended this power and for the first time in history have built up a Socialist State. The Japanese comrades must grasp this fact as soon as possible and establish in their country, in Japan, the power of the workers, peasants and soldiers.”

The Party and its press are conducting great work in exposing the class nature of the imperial army, making use for this purpose of the facts of the shooting of revolutionary units at the front. For instance, the Soldier’s Friend reported the following:

“In the beginning of January the soldiers of the N Company of the Himedzi division, stationed in Dziaranton (*All the Chinese geographical names are given in Japanese transcription) region, indignant at the delay in demobilization, began to return home arbitrarily, ignoring the orders of their commanders, and infecting other units by their example. The scared commanders of the division immediately surrounded the soldiers in revolt with a detachment which excelled them in numbers and arrested the soldiers who offered resistance. Two hundred men were arrested and shot.

“As one man, these Japanese soldiers showed firm resistance to the end and fell under the bullets of the Japanese imperialists with the revolutionary call: ‘Down with the imperialist war!’ ‘Evacuate the army from China!’” (Oct. 3, 1933.)

The Party removed from the pedestal the legend about the invincibility of the Japanese army by describing the defeats it suffered from the Chinese troops. “lsimoto, a spy of the Quantung army, was captured by the Chinese volunteer army in Jehol. Some time later, the Japanese commanders occupied this province under the pretext of releasing Isimoto. The volunteer army in Jehol valiantly resisted the Japanese invasion. On August 19, a detachment of 300 men destroyed the railway line in the vicinity of Nanrio, and attacked the headquarters of Yosioke, who was marching to the assistance of Isimoto. On August 20 a new battle took place which lasted several hours, the Japanese troops suffered a great loss, many being killed and wounded. Such is the stubborn resistance being offered to the invasion of Japanese imperialism into ‘Inner Mongolia’.” (Soldier’s Friend, Oct. 3, 1933.)

In explaining to the masses of soldiers that the “Manchurian bandits” whom the bourgeois press slanders and whom the Japanese commanders vainly endeavor to liquidate, are Chinese peasants, who defend their country from Japanese seizure with arms in their hands, the Soldier’s Friend shows with facts and figures how the poorly armed Chinese partisans, sometimes only possessing shotguns, defeat the Japanese troops, who excel them in numbers and in arms, and compel them to retreat. For instance:

“The armed workers and peasants, who are waging a stubborn struggle against the occupation of Manchuria by the Japanese troops and against the puppet Manchurian state, are organizing partisan detachments and are developing a movement throughout the whole of Manchuria.

“From August 1 to 20-a period of 20 days the partisans made 68 attacks on the South Manchurian Railway line and on August 21 they destroyed the railway bridge on the Kodzen river. A partisan detachment of 1,000 men attacked Eihan and destroyed the whole of the enemy’s forces. On August 28, the partisans raided Mukden. They seized airplanes, set fire to warehouses and airplanes, and disarmed a police detachment. In the morning of the 29th, a bitter fight followed, with the Japanese-Manchurian troops. On September 1, the partisans raided Mukden and Dainanmon for the second time. They surrounded the arsenal and gave battle. They were only armed with shotguns, rifles and machine guns. A four thousand strong partisan detachment was operating on the South Manchurian Railway near Sokston. On September 2, about 3,000 partisans attacked Kanto Sujka and engaged the Japanese Manchurian troops in a fierce battle. Nine partisans raided Deieskio, the railway track is broken. An armored train sent to the assistance of the Japanese units was compelled to retreat. This is how the partisans are fighting against the Japanese invasion in Manchuria and Mongolia, without sparing themselves.” (Soldier’s Friend, Oct. 3, 1933.)

Despite all its achievements the Party press had nevertheless a number of weak links in its activity. It is not enough to show the defeats that took place at the front. It is necessary that the C.P. of Japan explain systematically and intelligibly to the masses of soldiers and to the workers and peasants, the political meaning of revolutionary defeatism. Efforts should be made to ensure that the masses grasp that the military defeat of the Japanese monarchy is to the advantage of the proletariat and the peasantry, for it shatters the ground under the feet of the ruling classes and creates extensive opportunities for the toiling masses to attack the monarchy and to develop the revolutionary struggle. The propaganda of revolutionary defeatism is all the more necessary since the ruling classes of Japan, as well as all their agents, are increasingly scaring the masses with the danger of defeat, alleging that in such a case Japan would suffer the fate of China, colonial slavery, etc. The ruling classes skillfully utilize this argument for the military mobilization of the masses, for the suppression of the mass discontent of the workers at the enterprises, etc., deftly deceiving inexperienced workers sometimes, who, though not at all anxious to fight, nevertheless think that it is always better to choose the lesser evil.

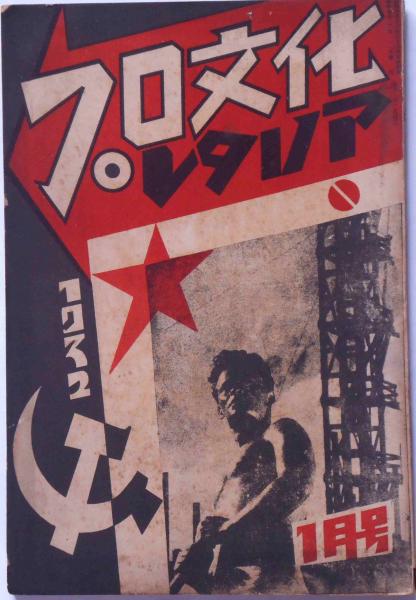

The struggle against fascism and social-fascism continues to remain the weak link in the activity of the press. In the issues of the Sekki which have reached us, we find directives issued to the Party organizations stating that the struggle against the fascists and social-fascists must be developed in the process of carrying out this or that campaign. But there are hardly any popular articles addressed to the mass reader, in which the paper attacks the concrete actions, activity and maneuvers of the fascists or exposes the fascization of the social-democratic upper stratum, although by their activity both these groups provide the richest material that could be used against themselves.

As regards the organizational work of the Communist Party in the army and navy, very little is mentioned due to the particularly conspirative nature of this work. In the same number of the Soldier’s Friend we find an article by a Communist, who tells about his experiences in organizational work in the barracks. Judging from this article the Party members who work in the army transfer the experience they have of the work of the revolutionary representatives at the enterprises.

When he landed in the barracks, the comrade first of all tried to find out the causes of discontent, and the demands of the soldiers. They are found to be as follows: free exit from the barracks; better food; the opportunity to read favorite books and newspapers; supply of three sets of clothes; mechanical laundry; abolition of compulsory training for bayonet fighting; complete abolition of work as domestic servants; wages at the rate of 1 yen per day; restitution of articles lost without any deduction or penalty; freedom of assembly and organization. These were part of the common demands of all the soldiers. In addition to these, there were a number of other demands depending upon the category of the units (infantry, cavalry, sapper troops, transport troops, etc.).

Then, the comrade became acquainted with the men and won authority among them.

“I began my work” he wrote, “by mapping out the following:

“1. To live on good terms with everybody, and gradually in the course of conversations to find out their moods and their biography.

“2. To strike up a close acquaintanceship, to enjoy the confidence of everybody and to gain their esteem (like the revolutionary representatives in the factories).

“3. Gradually I began to notice the results. Then in the process of getting to know them closer I proceeded to agitation and propaganda. For instance, when a great deal of laundering was to be done, I helped in the washing, saying that more time should be given for laundry, that washing should be done by machinery, and led the conversation from washing to the exposure of the essence of the army.”

The comrade very soon observed the results. All kinds of questions which troubled the recruits in the company were discussed with him and when any. difficulties arose as to what was to be done, they applied to him, while disputes arising between the recruits and the old soldiers were referred to him.

Then the comrade became the leader of the masses.

“I set myself,” he wrote, “the task of always being the head of everybody. This had to be carried out in the army with the greatest caution. You must not be either an extreme Left or an opportunist. You must without fail reflect the mood of everybody, linking up the common interests with the everyday requirements. I will give an example. On Sunday, this joyful day for the army, when the soldiers went on furlough, the young soldiers had a lot of work left. And it frequently happened that notwithstanding their great desire to go out, the new recruits refused to go out because they did not want to be together with the sergeants and the two-year-service men. They would have been more courageous had they been in larger numbers. Therefore, in spite of the abuse of the sergeants and of the two-year-service men I began to go on leave each time, attracting the timorous ones with me. This joint leave, which lasted several hours, made it possible to make the proper use of the time.”

Thus was the ground prepared for the setting up of a soldiers’ committee.

The Communists and the revolutionary Workers, who conducted anti-war work in the army units, showed a great deal of courage and inventiveness. Last January, in the 3rd battalion of the 7th regiment stationed in the City of Iticava, two soldiers were arrested, who were formerly workers, functionaries of the Dsenkaio. Not only did they themselves conduct work with the new recruits, but they succeeded in making the barracks accessible to other comrades. The bourgeois newspapers which reported their arrest, wrote: “Their daring went so far, that the Communists used to visit them directly in the battalion, as their friends, and thus the meetings took place openly in front of everybody.”

In such places where it was not yet possible to penetrate right into the very unit, the work was carried on from outside; they found out where the soldiers of the given barracks were in the habit of going on Sundays, such as the favorite soldiers’ saloons, etc., acquaintances were made, and connections were established. One bourgeois newspaper tells of this kind of work of a group of Communists and of Young Communists in Tsiba:

“They directed their efforts to the Bolshevization of the army units. They tried to strike up acquaintances ·with the soldiers, who went on furlough on Sundays, invited them to the restaurants, and conducted conversations and agitated.” (Sutz, July 15, 1933.)

Along with their activity in the units in the barracks, the Communists organized activity among the workers and the village youth, who were soon to enter the barracks. Reports about this appear in the bourgeois press from time to time, which publish police information about the investigations into the cases of arrested Party members.

Several teachers of primary schools were arrested in the Ibrarski prefecture last June. They made use of the opportunity to penetrate to the points where new recruits received preliminary training (where the teachers are generally invited to teach in addition to their basic occupation, and sometimes gratis, as a “social duty”) and developed anti-war agitation among the recruits there. (Sikai Undo Simbun of July 1, 1933.)

The same newspaper reports that in the Ivakuney district the Party members and the members of the proletarian cultural organizations carried on work among the youth of recruiting age: “They organized gatherings of the youth leaving for military service. At these gatherings they recited anti-army poems and anti-war songs. They urged the peasants to participate in the joint tilling of the land of the recruits’ families, and so forth”. (Sikai Undo, Simbun of Oct. 1, 1934.)

The bourgeois Japanese press hushes up the activity of the Communists in the army. Later on, sometimes a half year, or even a year later, where the police have lifted the prohibition, empty articles appear in the papers calculated to arouse sensation and to frighten the philistines.

But the Communist Party of Japan bravely conducts its heroic work in the army, at the front and inside the country. The Japanese Bolsheviks are for the third year holding high the banner of struggle to turn the imperialist war into a civil war, into a national revolution against the monarchy for rice, land, and liberty.

It was they who stood at the hand of the memorable soldiers’ riots in Kakey, in Shanghai and in Dzinkoo. It is they who conduct inconspicuous painstaking work on board the men-of-war and in the barracks to disintegrate the most powerful apparatus of Japanese imperialism-the “Emperor’s Army”.

Their experience, accumulated at the price of hundreds of the best revolutionary lives and of thousands of years of hard labor and imprisonment, deserves to be studied and popularized by the fraternal Communist Parties.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue:

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/vol-11/v11-n14-jul-20-1934-CI-USA-riaz-orig.pdf