Foster made an extended tour of the Soviet Union in 1925 (in part to argue his faction’s position before the Comintern) in which he visited a number of its leading, and newest, industrial centers. Still working under the N.E.P. in reconstructing the shattered economy after the wars and revolution, one of the cities visited was Ukraine’s Kharkov, on today’s front line in that lamentable war. His observations released as a pamphlet on his return, here is the chapter on ‘Kharkoff.’

‘Kharkoff’ by William Z. Foster from Russian Workers and Workshops in 1926. Labor Herald Library No. 16., Chicago 1926.

Kharkoff is the capital city of the Ukraine. It is an important and rapidly growing industrial center of approximately 450,000 inhabitants. The trade unions have a membership locally of 160,000, of whom 25,000 are metal workers. Like most of the Ukrainian cities, Kharkoff was the center of a bitter struggle during the civil wars. The government changed hands 13 times in 4 years. Many of the factories were practically demolished and production stopped in them by the counter-revolutionaries in these struggles.

We arrived in town about nine in the morning. The railroad yards were full of new and repaired cars–the long strings of dead engines and dilapidated freight cars which were, a few years ago, such a striking feature of Russian railroading are now practically eliminated. The streets were bustling with activity. Automobiles were on all sides. The girl “newsboys” were selling the local daily paper, “The Communist,” and everybody was reading it. We were accompanied by a delegate from Stalino to a local conference of the Communist Party. Heading for the trade union offices, we mounted a new auto-bus, one of many put upon the streets of Kharkoff in recent months. Most of the leading cities in Soviet Russia are installing these bus lines. Moscow has a dozen of them, established within the last 18 months. They are a big success. Many new buildings along our way to the immense “Palace of Labor” attested the fact that Kharkoff, like other Russian cities, is experiencing the beginning of a great building boom, which is bound to become more intense in the next few years.

An Agricultural Machinery Plant

We had only a dozen hours to spend in Kharkoff, so we had to make haste and to utilize our time fully. Further need for hurry was the fact that it was Saturday and the factories stopped work early. After the usual enthusiastic greeting by the leaders of the Communist Party and the Trade Unions, we were whirled away in an automobile from the Labor headquarters to the “Sickle and Hammer Harvester Works,” in company with Solovieff, secretary of the Kharkoff Metal Workers’ Union, and several local newspaper men. This plant manufactures a general line of harvesting machinery. It was formerly owned by a Russian company. It now employs 3,300 workers. As part of his general plan to ruin Russian industries so far as he could, the counter-revolutionary general, Denikin, practically destroyed this plant at the time he was forced to abandon Kharkoff.

At the time of our visit the plant was working full blast in an effort to satisfy the ravenous market for its products. The Russian peasants are developing a tremendous demand for agricultural machinery. This is only one phase of the great awakening, political and economic, that is taking place amongst them, and manifestations of which are to be seen on all sides as one travels through Soviet Russia. An interesting example we saw of this on our way to Stalino was the village Ulianov, named after Lenin. In this place the peasants have procured an electric motor, “hooked” it to a small stream nearby, and are lighting their village with electricity. The revolution is stirring the country districts as well as the cities.

The table below indicates the progress being made by the plant in increasing production. The extreme low tide of production was in 1920. Since then the recovery has been continuous and rapid. Production is now far in excess of the pre-war rate. It would be still greater but for a shortage in materials, which is gradually being overcome. An interesting detail on the materials question was great piles of broken machinery, to be used for scrap, that had been gathered all over the Ukraine from the factories shattered in the civil wars by the counter-revolutionaries.

The productivity of the individual workers is 120% of pre-war standards and is on the increase. Wages are considerably in excess of what they were under the old regime. All the workers are members of the Metal Workers’ Union. When passing through the wood working department, which employs 500 workers, I explained to the trade union officials accompanying us how American craft unionists would organize such a plant, with a dozen or more unions taking in the members of their respective crafts. They ridiculed such a primitive type of organization and said that anyone who should propose that for Soviet Russia would probably be adjudged insane. The principle of the Russian unions is to organize all the workers of a given industry, regardless of trade. color, nationality, or any other consideration, into one union. The workers are enthusiastic supporters of their national union, which has 680,000 members.

The plant is being rapidly extended and improved to meet the increasing demand. When passing through the foundry, where the molders had just finished pouring a heat, I stated that in the United States much of such work is done by machinery. The engineers assured me that they were fully aware of the backwardness of their equipment and were sparing no efforts to bring it up to date. Shortly afterwards they showed us, among the many other departments that are being built, a big structure of reinforced concrete that was being constructed for a modern foundry. Appliances for sanitation and safety, which were deemed needless luxuries in the old days, are being installed in all the plants.

The spirit of the workers was wonderful. It was just quitting time and they crowded about us. They proposed that we take greetings to the metal workers of America, and they insisted that we visit the beautiful “Lenin corners.” These are to be found in all Russian factories. In some plants we found as many as 30 of them. They are established right in the work places. They are usually a cluster of revolutionary pictures and literature. They are living symbols of the revolution.

An Electrical Plant

Bidding “Good Bye” to the workers in the Harvester Plant, we went to visit a big electrical plant not far away. We arrived just as the workers began to pour out in streams, homeward bound after their week’s work. This is a very important plant in Russian industry. It employs 5,000 workers, of whom 650 are women. The entire working force belongs to the Metal Workers’ Union. The plant was formerly owned by the General Electric Company of Germany.

The institution has an interesting history. Before the world war the German General Electric trust, wishing to extend its tentacles of control into Russia, planned this great factory. It had proceeded so far that the machinery of the plant was already constructed and had reached the docks of Riga when the war broke out. The Czar’s government immediate seized the plant and had it erected in 1916. When the revolution took place the Soviet government confiscated it. But the German capitalists were reluctant to let it go. When the Brest-Litovsk treaty was signed, one of the terms that were forced upon the Russians at the point of the bayonet was an agreement to pay for this plant, together with other German industries. However, to date these payments were never made.

The plant has modern equipment. It compares with the best American electrical factories. Its main section consists of a great concrete structure 400 yards long, admirably adapted to the work. It has a big power plant adjoining. The original cost of the institution was 12,000,000 roubles. The plant manufactures electrical appliances of all sorts, from electric bulbs to the biggest electrical machinery made in the history of Russia. It is swamped with orders for electrical apparatus from the mining, metal, railroad, and general transport industries. It is an especially important factor in producing the machinery for the great electrification project that is being put through for all of Soviet Russia. We were informed that so busy is the plant that commodities ordered now are contracted for delivery two years hence.

The present output is far in excess of the production of any previous time in the life of the plant. It is mounting by leaps and bounds, as evidenced by the following table:

Plans are being worked out for the extension of the plant. At present a big foundry is being built. The director informed us that the building program will double the capacity of the plant in three years. In all the departments the most modern methods are being introduced, the engineers being particularly enthusiastic to install the American conveyor system. All about this big plant one could see the tangible institutions of the new society taking shape. A big hospital was being built for the workers and a large number of new houses. The one complaint that we heard on all sides was the need for capital to finance the various developmental projects.

In the luxurious main offices of the plant, the atmosphere was intensely proletarian. On the walls hung the pictures of Lenin and other leaders of the revolution. In an inner room, which formerly was the sacred premises of the capitalist exploiters, the factory committee of the workers was holding a business meeting. As we talked to the chief engineer someone turned on the radio and we heard a chorus singing a revolutionary song in the local club of the Metal Workers’ Union.

We were shown about the plant by the Red Director, a Communist, who was formerly a worker at the bench. He spoke German, which brings to mind a peculiar condition which prevailed in pre-war Russian industry. Most of the mills, mines, and factories were owned by foreign capitalists. They were little nationalistic islands, so to speak, in Russia. The heads of the industries, the engineers, and the foremen, spoke the language of the foreign capitalist who owned the place. Remnants of this condition still exist, it being common to run onto workers and others in these plants who speak either French, German, or whatever was the language of the former owners.

The plant has an extensive technical staff of 250, of whom 30 are graduate engineers. This staff is making real progress in improving the products and production methods. The four highest paid engineers receive 350 roubles per month, which is about four times the average wage of a worker. The others get 300 roubles or less. Only a small fraction of these technical workers are Party members. These cannot receive more than the Party maximum of 225 roubles, which is the limit in wages allowed to any member of the Russian Communist Party, including even those occupying the highest Party and government posts.

This situation, with only a few of the technical experts in this key plant being members of the Communist Party; illustrates the pressing need for the development of revolutionary technicians. The workers are aware of this necessity, as the growth of technical schools indicates. In connection with this big electrical plant there is an excellent technical school, providing courses in all branches of electrical engineering. It is the best of its kind in Russia, and is so organized that even workers who cannot read are started on the way to the acquirement of technical knowledge. All the students are Communists. This school is making a definite contribution to the solution of the problem of producing revolutionary engineers and builders of the new society.

Another interesting feature of this plant was the mass education of apprentices that was going on. We saw large numbers of boys and girls being systematically instructed in the elements of the mechanical trades. A new class of beginners, numbering several score, were being taught in unison the fundamentals of filing and hammering. We inquired as to how the girls fared at learning the mechanical trades. The director was somewhat skeptical of their ability as machinists. Engineers in other plants we visited had a different opinion, maintaining that they were just as good workers as the boys. In many industries one encounters such mass training of apprentices. These young workers are recruits in the great army of skilled workers which Soviet Russia must create to satisfy the needs of her rapidly expanding industries.

The Metal Workers’ Club

After our visit to the agricultural machinery and electrical plants, the metal workers with us insisted that we go to inspect their club. It proved to be well worth our visit. It is housed in a big building, constructed in 1921. The club is an especially fine example of this new and vital workers’ institution, so popular in Soviet Russia. The headquarters of the Kharkoff Metal Workers’ Union is in the club. The club possesses a splendid theater and lecture hall together with numerous meeting rooms. It has a whole net work of chess, checker, and domino rooms. There is an elaborate radio equipment, a large buffet, general study rooms, and technical schools. An interesting current feature was an exhibition of Wall Journals from the various metal factories, prizes being offered for the most beautiful and effective. Many of the specimens were real works of art.

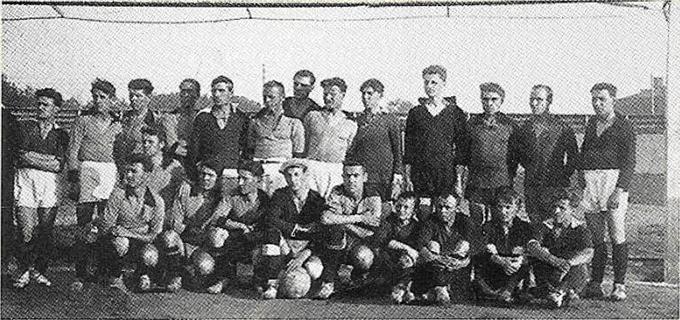

The club contains a special room for the M.O.P.R., or organization for the relief of working class political prisoners, and of course, a beautiful Lenin corner. The club has its own general orchestra, and also a special orchestra for the women; and in each of the local metal factories there is a band for mass marching by the workers. There is a department for the study of the construction and use of firearms, and another to teach mothers how to care for their children. The club has a splendid gymnasium, and close by is a big field for track and field sports. Over 1,000 members of this club take active part in these sports. The club has a fine library of 90,000 volumes and a special children’s library. The big library is of the circulating type, the various metal factories drawing books periodically for their own libraries. So hungry are the workers for knowledge that even this extensive library system is not enough. The Kharkoff Metal Workers’ Union has appropriated 60,000 roubles to buy more books. These workers may well be proud of their splendid club.

In the evening leaders of the Ukrainian Metal Workers paid us an “official Good Bye.” They gave us a parting supper, at which appeared our old friend Smirnoff of Ekaterinoslav. What rousing revolutionary speeches they made; what burning messages of solidarity they extended to American workers. We were honored and thrilled by these militant and veteran revolutionary fighters in the cause of Labor. After the speeches we made an auto trip through the town in a big Mercedes car owned by the local Metal Workers’ Union. Then came a hurried trip to catch the train to Moscow, where we proposed to stay a couple of days before going on to our next point of investigation, Leningrad. Our visit in Kharkoff, literally packed with interesting sights and happenings, was done. We had made the best of our 12 hours in town. It was of the most instructive and inspiring days of our lives.

The Labor Herald was the monthly publication of the Trade Union Educational League (TUEL), in immensely important link between the IWW of the 1910s and the CIO of the 1930s. It was begun by veteran labor organizer and Communist leader William Z. Foster in 1920 as an attempt to unite militants within various unions while continuing the industrial unionism tradition of the IWW, though it was opposed to “dual unionism” and favored the formation of a Labor Party. Although it would become financially supported by the Communist International and Communist Party of America, it remained autonomous, was a network and not a membership organization, and included many radicals outside the Communist Party. In 1924 Labor Herald was folded into Workers Monthly, an explicitly Party organ and in 1927 ‘Labor Unity’ became the organ of a now CP dominated TUEL. In 1929 and the turn towards Red Unions in the Third Period, TUEL was wound up and replaced by the Trade Union Unity League, a section of the Red International of Labor Unions (Profitern) and continued to publish Labor Unity until 1935. Labor Herald remains an important labor-orientated journal by revolutionaries in US left history and would be referenced by activists, along with TUEL, along after it’s heyday.

Link to PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/tuel/16-Russian%20Workers%201926.pdf