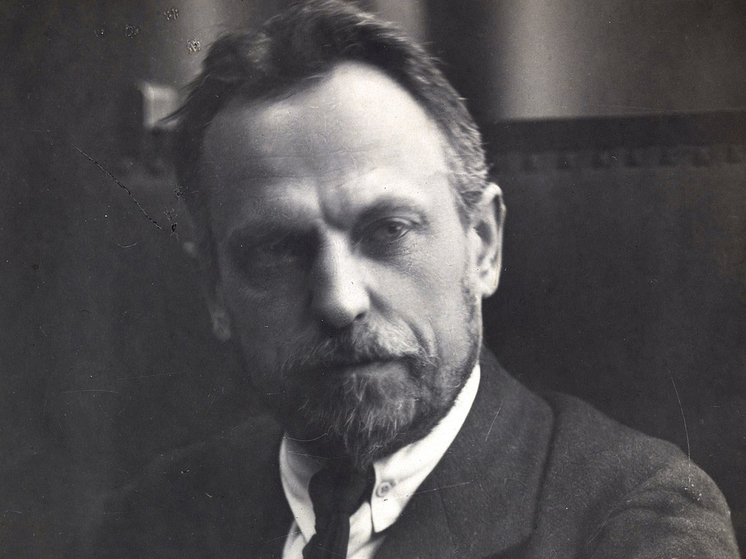

Tasked in 1918 as People’s Commissar of Health, Doctor Nikolai Semashko directed the pioneering public health care carried out by the Soviets in the first decade of the Revolution. Serving as Health Commissar until 1930, the preventative, child-focused, dispersed, and research driven system devised by him, the ‘Semashko System,’ would later be taken up in the Cuban Revolution where it remains the basis of their health programs today. Naturally, this work required the retention of existing scientists and intellectuals as well as the training of new ones. Here, he explains the conditions of ‘brain-workers’ in the U.S.S.R.

‘The Position of Intellectuals in the U.S.S.R.’ by Nikolai Semashko from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 6 No. 66. October 14, 1926.

The intellectuals in the U.S.S.R. did not at once come over to the side of the Soviet regime after the October Revolution. Those groups of intellectuals whose work was more closely bound up with the working and peasant masses, specially the village intelligentsia, adhered sooner to the new order; those groups however, who stood nearer to the old Tsarist regime or the order established by the bourgeois provisional government, resisted the Soviet regime during almost a whole year, either actively (by means of boycott and sabotage), or passively (striking on the job). The particularly irreconcilable section of the intellectuals the active workers of the anti-Soviet parties emigrated abroad.

It can now be quite definitively asserted that not a single intellectual profession has remained, the workers of which have not recognised the Soviet regime, exceptions being extremely rare. Not a single congress of professional workers takes place (teachers, doctors, engineers, agronomists, etc.) at which there are not resolutions in which the participants express their readiness to devote all their strength and knowledge to the cause of the new socialist construction.

The difficult years experienced by our country during the period of war, blockade and famine was naturally reflected in the Position of the intellectuals. During those times the life of the rural intelligentsia was relatively easier, as the village workers (doctors, teachers, agronomists) were nearer to the food-stocks than the town workers. Therefore in those days the task of the Soviet regime was to give main support to the town workers and especially the most highly qualified scientific forces. In the towns special rations were instituted a little more nutritive than those of the ordinary population, for doctors, engineers and technicians and for those serving in Soviet institutions. But particular care was taken to improve the position of scientific workers.

In 1921, on the initiative of V.I. Lenin, a commission was formed for improving the life of scientists. The members of this commission were M. Gorky, Khalakov (Food Commissariat), Semashko (Commissar for Health), Pokrovsky (Education Commissariat) and the late Prof. Karpov (Supreme Economic Council). At the time of formation the tasks of this commission included: alleviating the material position of scientists (supply of clothing, footwear, and also increased rations, fairly high for those days) as well as improving the living conditions of the scientists (defence of their housing rights, reductions and privileges in accommodation, supply of articles for scientific work, etc.). Besides this the Central Commission for improving the life of scientists gave every scientist a supplementary monetary grant in addition to his salary; the dimensions of this monitory grant depended upon the qualifications of the scientists.

It is generally recognised that this Commission rendered invaluable services to the scientists during those difficult years. It will remain a historic fact that the workers’ and peasants’ regime, at a moment when the population was starving, displayed exceptional solicitude in respect to the scientists; the workers and peasants, though themselves starving paid special attention to the material and spiritual needs of scientific workers. When the civil war came to an end and the economic and cultural life of the country began to revive, the Central Commission for improving the position of scientists was not dissolved. It still functions to this very day, having changed of course the methods of its work in accordance with the changed conditions.

The direct supply of food and clothing naturally stopped; but activity in serving the material and mental needs of the scientists was brought to the forefront.

For this purpose the Commission had above all to commence investigating the existing scientific forces in the U.S.S.R. A special qualification commission was formed from amongst the most prominent specialists in various branches of learning which examined the personal qualifications of every scientific worker and distributed them according to categories; first two categories scientific beginners; third category professors and teachers of the usual kind; fourth category specialists and teachers who have already formed their own! school and become prominent by their scientific work; and finally, the fifth category scientists having world fame. The Central Commission has performed tremendous services in that it has made known and established an accurate list of the qualifications of all scientific forces of which the U.S.S.R. disposes. In accordance with the qualification, scientists continued to receive supplementary monetary grants. The Commission also grants relief for illnesses, accidents, etc., both to the scientists themselves and to the members of their families.

The Commission has got a number of laws passed tending to improve the position of scientists in respect to accommodation (right to supplementary floor space; reductions in rent; prohibition of evictions, etc.). The Commission has a free legal consultation for scientists.

The Central Commission has paid special attention to the position of invalid and aged scientists. For invalids, besides the usual institutions, special rest homes have been organised near Moscow, Leningrad and in certain other places and also sanatoria in the Crimea (the former Gaspra) and in the Caucasus. A total number of 5,000 scientists undergo cures every year in the rest homes and sanatoria of the Commission. Two hostels have been instituted for aged scientists one in Moscow and the other in Leningrad.

For scientists arriving in Moscow on scientific missions, a special hostel has been organised where they may get complete board for a modest price.

Of extreme interest are the “Scientists’ Houses” in Moscow, Leningrad, Kharkoff and many other university towns. In these Houses clubs are organised and there are extensive libraries and reading rooms. At the yearly meetings reports are given on various scientific themes, and concerts, readings of compositions, evenings, etc., given. These Scientists’ Houses are centres where the scientific workers of various specialties come into contact with those of other professions and thus diminish the one-sidedness of their own specialty. These Scientists’ Houses conduct extensive cultural-educational work amongst the toiling population: the scientists give lectures in workers’ clubs, and broadcast lectures by radio, etc.

Thus up to the present the Soviet regime is continuing to display special care towards the scientific workers in the U.S.S.R., alleviating their material and spiritual position.

Along with the economic and cultural revival of the country an improvement in the position of the intellectuals is also to be noticed. Wages in all professions without exception are rising. There is a rapid growth in the cultural demands of the population and consequently also in the demand for intellectual labour. There are very few countries anywhere else in the world where scientific work has proceeded so intensively in all fields as in the U.S.S.R.

During the last few years the Soviet regime has been paying special attention to rural workers. Their position both in a cultural and material respect, is of course worse than that of the towns. The economic and cultural revival of the countryside has demanded that particular attention be paid to the rural intelligentsia. A number of measures have been taken in this direction.

First of all the salaries of village doctors, agronomists and teachers have been raised. Further, in order to keep these salaries from dropping below a certain minimum, a system of State subsidies to the local budget has been established, i.e. the State has participated in the expenditure on salaries for these Workers on condition that the remaining part was paid by the local budget, not below a minimum established by the State.

Material conditions of service are assured by special decrees (supply of accommodation with lighting and heating, travelling expenses); privileges are given for the children of these workers (for entering schools and higher scholastic institutions), while periodical rises are given for long service; there is also periodical granting of leave for these intellectual workers to perfect their knowledge; finally social insurance in case of loss of labour capacity, etc.

Thanks to these measures the villages are afforded greater possibilities of obtaining the development of intellectual forces they need.

The Soviet intellectuals are growing up in closer and closer unity with the toiling masses of the US.S.R. This process of unity is proceeding all the more rapidly as new cadres of intellectuals are coming from the ranks of the workers and peasants themselves. The workers and peasants of the U.S.S.R. are flooding more and more not only into the schools but also into the higher colleges. Of course the conditions of life and work of the Soviet intelligentsia are still far from being ideal. But they know that the improvement of these conditions depends upon the successes of further construction. Therefore they have bound up their cause with that of the workers and peasants of the U.S.S.R. The Soviet intellectuals are becoming more and more flesh of the flesh and blood of the blood of the workers and peasants.

In the U.S.S.R. the great dream of Lassalle of the unification of science and labour is being realised.