Nat Ross, Communist Party Southern District Organizer, with a three-part report on the significance of the struggle of the Share Croppers Union in Tallapoosa County, Alabama and the role of the Party in leadership.

‘The Significance of the Present Struggles in Alabama’ by Nat Ross from The Daily Worker. Vols. 9 & 10 Nos. 313, 1 & 2. December 31, 1932, January 2 & 3, 1933.

I.

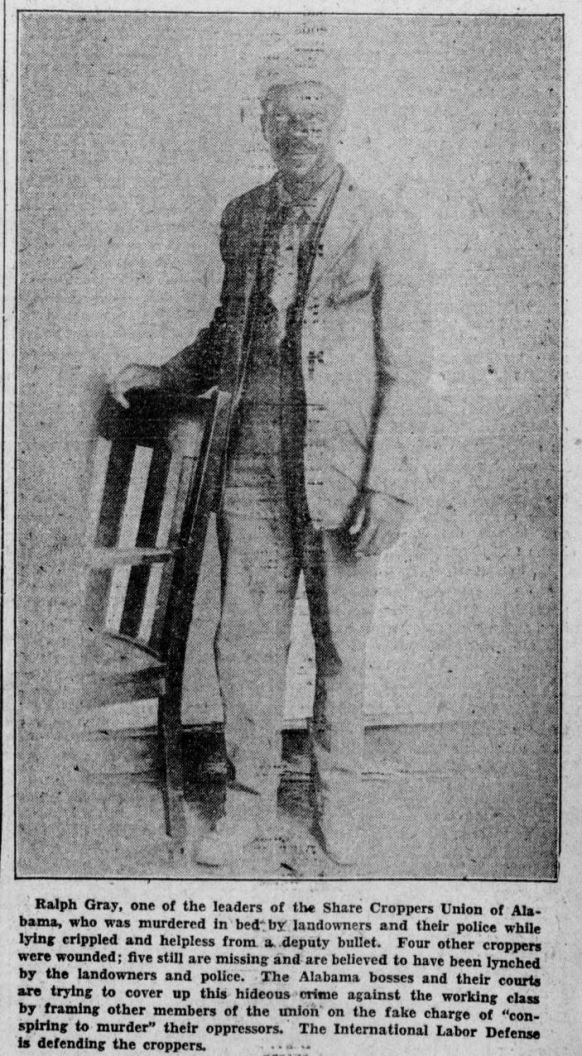

On Dec. 19 a sharp battle took place in Reeltown (Notasulga), Tallapoosa County, just 15 miles from Camp Hill, scene of the historic struggle of the Negro croppers and farmers in July, 1931. Reeltown is a continuation of the Camp Hill struggle on a much higher political and organizational plane. At Camp Hill the armed mob broke into a mass meeting of the Share Croppers’ Union held in a church, the result being the killing of the Negro farmer, Ralph Grey, and an unknown number of others, and the arrest of 30 other croppers. The nation-wide protests, the release of all arrested, the forcing of immediate concessions from the landlords in the way of relief and extension of credits, showed the Negro people that the way of revolutionary mass struggle was the correct way.

In the Camp Hill struggle the sheriff’s force succeeded in getting large numbers of poor white farmers in the lynch mob with the lies that the Negroes wanted to take the land and women away from ALL the white people. But the poor whites began to realize their mistake when they saw the concessions forced on the landlords by the struggle.

ORGANIZER SENT INTO FIELD

In the summer of 1932 an organizer was sent into the field, the Union was re-established on a correct organizational form with a committee of 10 or so based on the plantation or locality forming a local. Mass meetings were discontinued except on special occasions, such as Anti-War day, when the meeting was held illegally. All meetings were to be held illegally until the Union was strong enough to come out in the open. It was not long before many locals were organized in Tallapoosa, Macon, Lee, Chambers and Elmore Counties, composed of Negro farm workers, croppers and tenants, their wives and children. Leaflets were distributed and the croppers began to move against hunger in the most elementary forms of struggle. Every struggle forced a concession, because the landlords well knew that the croppers were organizing to fight and not to starve to death. On one large plantation the croppers won the important right to sell their own cotton. On another the landlord was forced to give a cropper and his family an order for clothes as well as cash relief. On another plantation, the landlord, George Harper, demanded that many croppers move off his place and leave all their belongings, but after the increased activity of the union, withdrew his threat and cancelled all debts, some of them running up to $300. The landlords then tried to halt the growth of the union by trying to frame Euther Hugley for distribution of leaflets, but this scheme was defeated by mass defense. At the same time (Dec. 5) the farmer-delegates from the five counties named were leaving for Washington to attend the National Farmers’ Relief Conference. The white farmers were drawing closer to the Union, which they began to see was fighting for the needs of the entire poor farming population.

LET us for a minute glance at the beastly economic, political and social oppression of the Negro people. Quotations from some letters from this “Black Belt” section will explain the condition in the words of the croppers themselves.

“We work on a farm this year and I and my children are naked and barefooted and my husband can’t get any clothes at all. We work hard and don’t get anything out of it.”

“My wife is ordered to go to the fields (to work) sick or well.”, “My boss lady she claim to be sick and got me stay 2 weeks and the pay she give me is an old dress and told me she would look up something else sometime.”

“I work for Mrs. Clary Pogue for wages and my wife has a crop and Mrs. Pogue is trying to run me off so she can get the crop. She don’t pay me at all and her brother tried to jump on me and I can’t stay at home at all. She said if I come on the place she will shoot me. And my wife work at her house and she don’t pay her anything and told her she was going to let her have a little meal and she better not slip me none of it. I worked all the week and asked for some groceries for next week and her brother came and cursed me and told me I had not done a damn thing. And Mrs. Clary got the sheriff and he came after me on Monday and I dodge him. He left word that if I don’t move he would lock me up and I ain’t got nowhere to go.”.

“I made two bales of cotton. I have to pay rent out of it and the and my family have to live out of what was left this winter. If I buy food I won’t have nothing to buy clothes with. The landlord would not let me have a foot of land to plant corn. I have been working for $5 a month to feed 11 in the family. I am planning and studying to see what way can be done to have me a crop next year and I want some information on what to do. The landlord don’t want to rent me no land. He wants me to share crop and I want to work different from that.”

“Our children want to go to school and have no clothes to wear and have no shoes and no fit food for lunch and live a long ways and have to walk out on the road and ditches and in the field to let the white school bus pass by. We have no money to buy our children books and the white children get them free. The colored school ain’t started yet and the superintendent says it won’t start.”

This, in brief, is the objective situation in which the battle of Reeltown took place.

THE SHERIFF ARRIVES

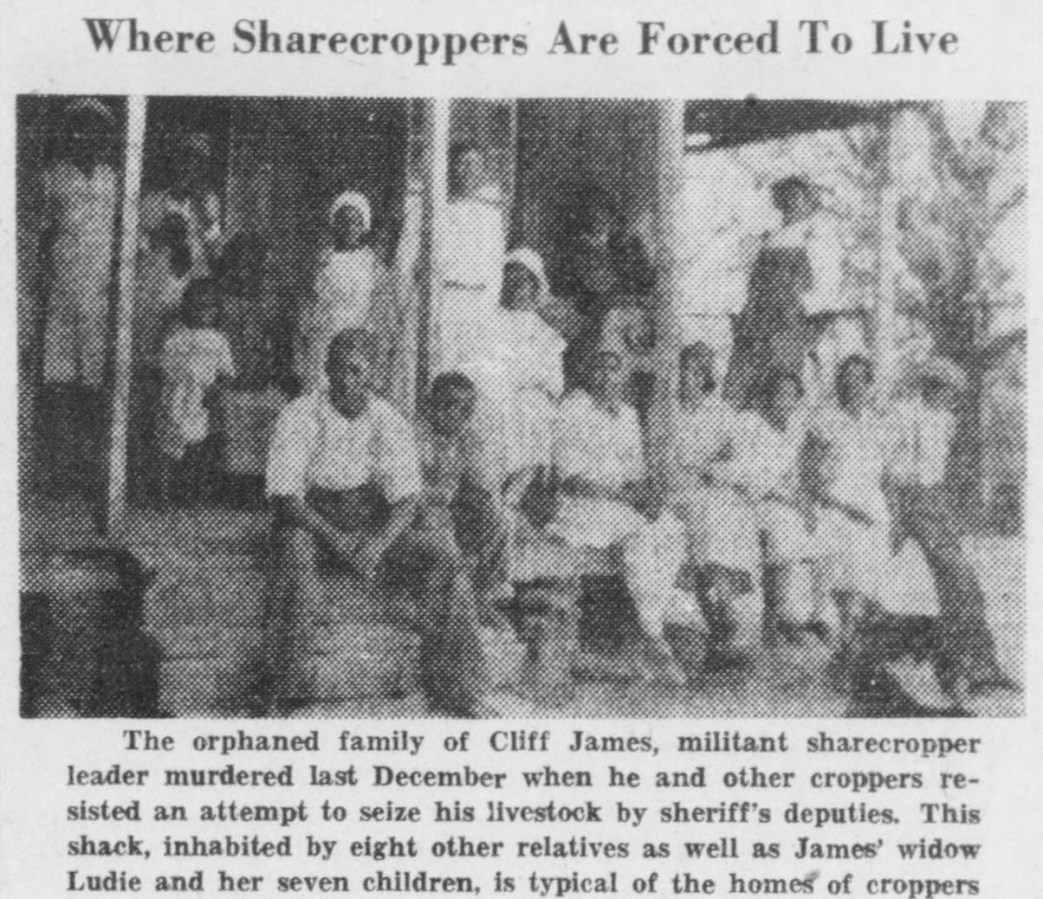

On Monday morning, Dec. 19, Deputy Elder came to the farm of Clifford James, a Negro farmer, with an order gotten out by Walter Parker, rich merchant of Notasulga, who had a mortgage on the farm, to take away his mule and cow.

James, backed by about 10 members of the union who had gathered, properly refused to give up his last and only means of livelihood. It seems from reports that the merchant had no legal right even according to the capitalist law, to the animals. The deputy left saying, “I’m going back to get some more men and kill you all in a pile.”

When Deputy Elder returned with three other armed white thugs, about 50 Negroes had gathered in James’ shack, determined not to give up the live stock. After all, they thought, it was better to stand together and insist on the right to live than to die of starvation; for that is it what it meant for a poor tenant to be without a mule and cow. It was then that the battle began.

Of course, according to the press reports which came only from the deputies themselves, the Negroes were first to fire. Elder said that two Negroes came out to tell the deputies they would not yield the animals and then as they returned to enter the house the Negroes inside opened fire and wounded a couple of the deputies. The deputies returned the fire, killing Jim McMullin inside the house and wounding about fifteen, including a 12-year-old boy. Even in this story the obvious lie that the Negroes started firing stands out. Why did the two Negroes come out to speak to the armed deputies? How come that the Negroes were killed and wounded inside the house? How about the threat of Elder? How is it that the deputies were slightly wounded when it is clear that the armed croppers were’ able to shoot to kill if they wished? Why did Sheriff Young forbid newspaper men to approach the shack after the battle and even destroyed the photographs of the Birmingham News reporter, which action seemed so obviously raw that even the lynch press criticized the stupid sheriff for his indiscretion. It was clear from the outset that the murderous deputies came and shot into the croppers deliberately and the croppers answered the shots in self-defense, in defending the right to live, in refusing to give up their stock even at the point of an armed attack of the agents of the oppressors.

THE landlords and their armed thugs were infuriated. The Negro masses had shown that they were ready to defend their lives and means of life. They were organized solidly into a revolutionary union. This must be crushed. A call was made for the whites to join the posse to put down the “race riot.” Sheriff Young refused to say anything to the press except that “they hadn’t started doing anything yet.” The sheriff, following orders from the landlords, was planning on a real massacre of the Negroes in the vicinity. This was as clear as crystal the afternoon of Dec. 19. The sheriff informed Governor Miller that the situation was grave and to hold the soldiers ready. The adjutant general rushed to the scene of action.

POSSE GOES INTO ACTION.

In the meantime the posse went into action. They numbered about 100 to 200 and they came from five counties. The posse included the sheriffs and deputies from four counties, but almost no white poor farmers. The posse hunted the Negroes everywhere, chased them over hills and into woods and swamps. This barbarous and feverish man-hunt continued for 24 hours, the result being a dozen Negroes arrested and charged with intent to murder, and an unknown number killed and wounded. While the latest statement is one cropper killed, this is probably untrue, since Sheriff Stearn admitted seeing three dead himself and a report to the adjutant was that four were dead. It is probable that as many as a dozen Negroes were killed and certainly at least five. After the first day the sheriff of Elmore County announced that only one of the three arrested were in jail, the other two “may have been released.” No doubt they were shot dead in the dark of the night by the Elmore deputies.

After all the terrible threats of Sheriff Young, in charge of the man-hunt, it is well to ask why all of a sudden the lynch mob was called upon to disperse?

UNITY OF NEGRO AND WHITE

First, the white ruling class and its armed murderers–despite all their shouts of race riot–despite all their lies about the threats against the Negro farmers by the white farmers, could not enlist the poor whites to join the man-hunt. The outstanding fact in this struggle was the remarkable unity of Negro and white farmers, a thing unknown in the ‘Black Belt’ heretofore. After calling this struggle a race riot, inter-racial clash, etc., the Birmingham Post is forced to come out in its feature editorial on Thursday, headed “No Race Riot,” saying: “It would be exceedingly superficial to regard the disturbance as a race riot. The relatively small extent to which race prejudice factored in the affair is one of the things that impressed newspaper reporters most deeply”

“The cause of the trouble was essentially economic rather than racial. The resistance of the Negroes at Reeltown against officers seeking to attach their livestock bears a close parallel to battles fought, in Iowa and Wisconsin between farmers and sheriffs deputies seeking to serve eviction papers. A good many white farmers, ground down by the same relentless economic pressure from which the Negroes were suffering, expressed sympathy with the Negroes’ desperate plight.”

A news item in the same paper states; “while farmers in the vicinity do not regard the disturbances primarily as a race riot although it was incited by Communist literature (!) The literature has been distributed in the mail boxes of both white and Negro farmers for the past 18 months and urge radical action by white and Negro farmers alike.”

II. “Lynch Masters Know Their Enemies–And Their Friends.” January 2, 1933.

Despite all attempts of the landlords and their murder agents and the entire capitalist press including part of the Southern Negro reformist press to whip the white farmers into a lynch spirit against the Negro farmers, the scheme failed. Instead, the white toilers in the Black Belt united with the Negro farmers in helping them escape, in caring for the wounded, in protesting Sheriff Young’s actions, in gathering in large crowds on the highways, in watching the action of the posse to such an extent that when Sheriff Young called off the man-hunt, he declared he was afraid some innocent citizens might get hurt. When all the details are known, it will be established that the white croppers and farmers no doubt joined and united with the Negroes against a mob of murderers.

THE white farmers in this territory had seen the union gain partial victories for the Negroes which affected them. They saw the Union was fighting for their own needs. They saw power behind the union, especially in gaining the acquittal of Hugley. They were recognizing that the race issue was a hoax to hide the class struggle. And they knew the demands of the union were the demands of all the toiling farmers, croppers and laborers, both black and white. These demands were:

1. Minimum price of 10 cents for cotton.

2. The right to sell own cotton.

3. No forced pooling of cotton.

4. No confiscation of the live-stock or attachment of farm implements.

5. No evictions, forced collections of debts.

6. Free school buses for children without discrimination against Negro students.

7. The right to organize for bread and fight against terror and war.

The second major reason why the man hunt was called off was due to the heroism of the Negro croppers. They were fighting with the determination of people who know what they are fighting for. On Tuesday afternoon just before the man hunt was called off the press reports that “leaders of the posse received information that the Negroes (who had taken part in the battle against the deputies) had sworn to resist all efforts to place them under arrest. Another gun battle was expected when these Negroes were found.” Another story relates how one Negro got away into a swamp from a posse of 10 who shot at him six times. Another item reports that the “Negroes were seen in every town in the county and at their homes along the road by newspapermen who followed the activities of the posse despite Sheriff Young’s orders.” In other words the Negro masses did not hide but were out in the open protesting and following every step of the lynch mob. The mob feared the power of the Negro masses. And for that matter, the white toilers were right with them and the boundless energy, courage and ingenuity of the Negroes hunted in the struggle, was an inspiration to the poor masses of the countryside. That is why things became too hot for Sheriff Young and his murder crew.

FLOODED WITH PROTESTS.

And finally the flood of protests and telegrams from every part of the country (which in many cases were printed in the press in full) was a sledge hammer blow to the Alabama ruling class and their hired thugs. Any one who doubts the effect of mass protest should see some of the southern papers and any one who also happens to doubt the importance of the Daily Worker should have been in the South or in Birmingham and imagined the knock-out effect the “Daily” of Dec. 21 had on the ruling class and the inspiration and power it gave to the masses. This whole flood of telegrams and the struggle in the “Black Belt” simply staggered the ruling class and sharply brought out the deepening crisis in Alabama. It was not entirely accidental that on Dec. 20 Gov. Miller called another special session of the state legislature to convene on Jan. 21 and that day Representative Lovelace of Tallapoosa county declared that he will have a bill passed in the legislation to enable courts to convict on “sedition” and “inciting to riot”.

This is very important for landlord Lovelace because he himself admits that “all the Negro tenants on my farm are on the mailing list of some Communist organization in Birmingham”. The fact

that one third of the schools thruout the state involving 125,000 children are closed down and that tax strikes are spreading, forced the millionaire Will Leedy to say that these actions “smack of Communism and would serve to further the ends of a group of Communists of Birmingham who are bent on bringing chaos to the state.”

In these first few days of the struggle the united front was created between the finance capitalists of Birmingham headed by the Tennessee Company (U. S. Steel), the big landlords of southern and central Alabama the Negro reformist leaders and other agents of the lynch masters. The main line was a savage attack on the Communist Party. First the press shouted in its headlines that the struggle was a race riot, race war, inter-racial clash etc. in an attempt to have more blood spilled. The wish was father to the thought. For this purpose lying stories were invented the first two days. Is it any wonder that many people are thinking how is it possible for the lynch inciting press to call the Communist Party “drill sergeants of hatred” and “harpies that spring up in troubled times”? But lies do not stop the lynchers from frothing at the mouth. The Inter-racial committee of Alabama-Tennessee consisting of white bosses Negro reformist leaders says among other things: “Certain sinister, alien, influences are at work seeking to sow discord between black and white. Behind the malevolent activity there is able leadership, tireless energy, worldwide organization. Communism in its hope of world revolution has chosen the southern Negro as the American group most likely to respond to their revolutionary appeal.” Having failed to “create a race riot” the press in its editorials begins to deplore the episode. A typical editorial says the following: “The deplorable affair in Tallapoosa County is an example of what comes of the activities of Communist agitators who prey upon ignorant Negroes in these times of unrest, and stirring up bitterness among them.” Not a word is said about the deplorable conditions under which both Negro and white farmers live in the Alabama Black Belt. Not a word is said about the issue involved, namely the struggle for the RIGHT TO LIVE. The only trouble it seems, is that the Communists are making the “good Negro” as “bad Negroes” that the Negroes ‘naturally” accept the customary barbarism of the South peacefully but that the Reds simply stir up these ‘ignorant Negroes” to protest their conditions. Such is the line of many of the Southern papers who echo the interests of the rich.

WHILE the lynch masters know their enemies they also know their friends. The landlords have come to recognize the ASSISTANT HANGMEN of the Negro masses are the Negro reformist leaders. Quotations from editorials from the Post and Age-Herald declare: “That the dreadful affair should have taken place in a section ornamented by so useful and hopeful and enterprise as Tuskegee Institute serves only to deepen one’s sense of defeat.” (Post) “Happening in the shadow of Tuskegee Institute where Booker T. Washington preached his sermon of racial co-operation and where Robert R. Moton has carried the work on since, these incidents are doubly unfortunate.” (Age-Herald) It is clear that the capitalists and landlords see the Negro masses slipping away from the control of their shrewdest betrayers, the Negro reformists, and turning to Communism. How well they regret it. The role of assistant hangman in the Alabama croppers struggle which the misleaders are called on to play is grabbed at by most of the Southern Negro newspapers, who are dominated by the ideology of the churches, big lodges and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

SEEK TO SMASH PARTY

Long articles discussing ways and means of smashing the Communist Party, appear daily. Attorney General Knight of Scottsboro infamy promises to prosecute the District leaders “responsible” for the “Tallapoosa riots.” The Birmingham police are congratulated for keeping tabs on “the Red ‘leaders.” They quickly raided the office of the I.L.D. the day after the Reeltown battle. They break into a private house meeting and jail Alice Burke. They shout that the Birmingham leaders are responsible for telling the croppers that “the war question should be the daily agitation of all the comrades,” they declare that the Birmingham leaders are teaching the Negro masses the principles of Sovietism, of the workers owning the mills and land with the capitalists overthrown, and the elimination of racial and social lines.”

It is clearly necessary to prepare for the sharp terror that is coming.

ON the whole the District leadership of the Party reacted quickly and correctly to the first news of the struggle. Our fundamental line was correct–that it was planned murderous attack by landlords armed deputies on Negro poor farmers defending themselves and their means of livelihood which the landlords could not turn into a “race riot” because of the tremendous support given the heroic Negroes by the toiling whites. We issued publicity leaflets and resolutions quickly, our leadership worked tirelessly and the entire District membership was swept into motion, organizers went into the field, legal defense was put into action, a committee left to see the Governor etc. But aside from this, many bad mistakes cropped up the first few days, growing primarily out of a failure to understand the Leninist approach to the national question, a blurring over of the national aspects of the Negro question. One comrade thought that we were pushing the Scottsboro case aside by taking up the fight for the Alabama croppers. This comrade did not understand that the struggle of the Alabama croppers and the Scottsboro case must be linked up, that they both stand on common ground, the struggle for Negro rights and against the whole system of Negro oppression.

Even the capitalist press admitted that the croppers gave “a featured place to the Scottsboro case in all their agitation.” Another comrade put forward a resolution saying that the condition of the white farmers were just as bad as the Negro farmers, which of course is absolutely untrue. In one resolution the winning of the white workers was placed on the basis of blurring over the Negro question.

III. Leadership in the Struggle of the Alabama Share Croppers. January 3, 1933.

Another serious mistake made was that the District did not prepare for the struggle which was clearly ahead and therefore lost all direct contact because the mail was held up in the first days of bloody struggle. We also failed to prepare the croppers to carry on a mass protest campaign and to be able to work under the most savage terror. Another of our District comrades, on reading a batch of letters form the croppers and farmers, did not try to sense their mood for struggle but thought they were not politically “developed” because their language was not on a highly Marxian plane. And finally, there was resistance from one of our comrades the first day or so when we said that even from lying press reports it was obvious that the most historic achievement was the unity of the black and white toiling farmers. Here it might be mentioned that the extent to which news about revolutionary struggle is distorted is seen in the fact that the final returns for Foster and Ford given out by the Associated Press for Alabama was 240 votes but on Dec. 21, the press issues a statement that in Elmore county adjoining Tallapoosa, Foster and Ford received 275 votes, according to official returns!

THE Reeltown battle shows the correctness of the Communist line. The struggle and all its many concrete manifestations must be used as an historical laboratory where the masses can learn in simple fashion the Communist position on the Negro question, the struggle for self-determination etc. It must be used to expose all the fascists and social fascists and in particular the treacherous role of the Negro reformists Socialists and leaders who declare that the Communist method leads to “race war” in the Black Belt. Well, Mr. Norman Thomas, your friends, the landlords, sheriffs and the entire, lynch press tried their best to please you but the masses instinctively and under conscious guidance took the Communist way of struggle, the way of united struggle of Negro and white toiling farmers against the landlords and their lynch mobs in defense of the oppressed Negroes, right in the heart of the Black Belt. It is necessary to explain the whole question of seizure of the land, land tenure, withdrawal of the armed forces, the right of the Negro majority to decide for themselves the form of government they want in the Black Belt, the drawing in of the white masses on the basis of equal rights for all toilers: to concertize on the basis of this new historical struggle, the meaning of the Communist slogan, “Absolute Equal Rights for Negroes and Self Determination for the Black Belt.”

Especially is it important to show how intimately the struggle for immediate needs has already been linked up with the struggle for the land, for the “principles of Sovietism,” for the struggle against war. The unity between the immediate burning needs of the toiling Negro farmers and their basic revolutionary needs stood out in the battle of Reeltown. The Lenin Memorial campaign must be used especially for political clarity.

It is necessary to go into detail on the Leninist principle of the hegemony of the proletariat over all strata of the toiling population. In this respect the black and white proletariat of Birmingham played a decisive role under the guidance of the Communist Party. From the moment of the outbreak of the Reeltown struggle the Party led the advanced industrial proletariat of Birmingham to support and actual guidance of the toilers in the Black Belt in their fight for their immediate agrarian and national needs and for the right of the Negro people to complete liberation. The ruling class recognized this, which resulted in the frenzied attack on the Party leadership in Birmingham and even the silent Sheriff Young curtly blurted out, “I’m already being bothered by telegrams from Birmingham Communists.” These are a few of the lessons that we must bring to the Party throughout the South in particular.

BIG ORGANIZATIONAL TASKS

There are immediate big organizational tasks. It is imperative now to redouble our efforts in building the Share Croppers Union. We must build the union on a stronger basis in the scene of struggle. White farmers must be drawn into the Union locals (meeting separately in cases) and where this is not possible, white farmers should be drawn into committees of action. The organized unity of Negro and white farmers will raise the whole struggle on a higher plane, will force greater concessions. The union must not be confined to the five or six counties in Alabama but must spread throughout the Black Belt. We must find ways and means (and they can be found) to organize the toiling farmers, especially since the Reeltown struggle has found the first page of most southern papers.

It is of first importance to build the I.L.D. on a bigger scale. This must be done in connection with the defense of the Alabama croppers. The I.L.D., supported, by the masses, must force absolute release of all croppers, punishment of the sheriffs, demand an investigation into the murders of unknown croppers, demand that the county and state government give relief to the families of dead and wounded croppers. It is necessary to link up this defense struggle with the fight for the Scottsboro boys and make it a permanently increasing struggle against the whole system of lynching and Negro oppression. Especially must the I.L.D. come out using every available worker and intellectual in the fight for free speech, not only in Birmingham and in Atlanta (Herndon case), but in the Black Belt as well. Already the sheriffs of the three counties in the Black Belt have stated that they have made plans for extensive under-cover work, not only to prevent the distribution of propaganda but the apprehension of those who attempt it.” In this respect mass meetings called by the I.L.D. in the larger Southern cities will be a big step forward.

ABOVE all and standing out as the decisive task is the building of the Communist Party. Particularly in the South, only the conscious, relentless, bold leadership of the Party can smash through the outbursts of savage terror. At this time, when tens of thousands of people are in motion as a result of the Reeltown struggle, our first duty becomes the drawing in of hundreds of these elements in the Black Belt, in the large Southern cities, into the Party. A strong Party, composed of the most militant section of Negro and white toilers, is the only guarantee that the croppers struggles will be raised to higher levels, that the Black Belt will witness sharper battles, which will turn the struggle for immediate needs into the struggle for power of the Negro majority. In this way the Negro people will form an ever-stronger ally of the revolutionary working class, uniting with the white toiling masses for the main struggle, the setting up of a workers and farmers government in the United States…

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1932/v09-n313-NY-dec-31-1932-DW-LOC.pdf

PDF of issue 2: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1933/v010-n001-Nat-jan-02-1933-DW-LOC.pdf

PDF of issue 3: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1933/v010-n002-NY-jan-03-1933-DW-LOC.pdf