Arguably, 1931 was the year World War Two began in the Pacific. Imperialist Japan seethed with internal strife seeing two attempted right-wing coups that year; and as described below, a rising wave of class struggles. An expansionist Japanese military conducted several bona fide ‘false flag’ events on a divided China, then embroiled in multiple civil wars, to justify its September invasion and occupation of Manchuria. Below is a Comintern document on the war, the internal situation of Japan, strikes and peasant struggles, opposition to the war, the tasks of the Japanese Communist Party and a debate on the character of the Japanese revolution.

‘The Situation in Japan and the Tasks of the Japanese Communist Party’ from Communist International. Vol. 9 No. 7. April 15, 1932.

THE SITUATION IN JAPAN AND THE TASKS OF THE JAPANESE COMMUNIST PARTY

MODERN Japan is in the throes of an unparalleled, widespread and ever-growing economic crisis. The foreign trade of Japan has drastically declined during the past years. In 1930, the Japanese exports dropped by 32 per cent. and the imports by 30 per cent. compared with 1929. During the past year of 1931 another sharp decline of the Japanese foreign trade was recorded, exports falling by 22 per cent. and imports by 21.5 per cent. against the previous year. Industry is working at less than half capacity. During the last two years the cotton industry reduced operations by 47 per cent., the engineering industry by 34 per cent., the shipbuilding industry by 70 per cent., the steel industry by 38.7 per cent., etc.

The reduction of output has been accompanied by a drastic cut of the number of workers employed in industry. During 1930, and especially during 1931, there were mass discharges of workers from various undertakings. The army of unemployed in Japan has reached the enormous figure of three million. But the effect of the crisis has been particularly disastrous in agriculture. The worst to suffer were the rice and silkbreeding plantations. Despite the crop failure of 1931, resulting in a general decrease of agricultural production by 20 per cent., the prices of rice continue to decline, this being accompanied by an ever-growing destruction of the productive forces of agriculture, by the ruination and pauperisation of the peasant masses. The prospect of a financial collapse is also becoming more and more threatening and imminent. The gold reserves during the past two years have sunk to less than half, from 1,124 million yen in January, 1930, to 521 million yen in December, 1931. The private deposits in the Japanese banks have been reduced during the same period by more the 3.5 times.

It is quite clear that the crisis of the national economy of Japan is interconnected with, and directly affected by the modern world economic crisis. But on the other hand, the causes which gave rise to it, its force and depth must be explained by the structure of Japan’s economy and social system.

Here it is necessary first of all to emphasise the backward, Asiatic, semi-feudal system prevailing in the Japanese village. The landlord estates play a predominant part in Japanese agriculture. Seventy per cent. of the Japanese farms (3,836,000) are poor farms restricted to less than one hectare of land each. All of these farmers are forced to lease land from the landlords under the most slavish conditions. It is characteristic that the acreage of the landlords’ estates during the last 50 years (that is precisely during the years of the speedy capitalist development of the country) not only has not decreased but has, on the contrary, noticeably increased, from 36 per cent. to 46 per cent. of the total cultivated area. During this half century the ruinous rents, the semi-feudal exploitation not only affected fresh sections of the peasantry but assumed even more oppressive forms. We refer to the steady rise of the rentals during the past decades. Thus if the rent payments for 1886 are taken as 100, those for 1909-1913 are equal to 113 per cent., and those for 1917-1921 to 117 per cent.

The Japanese landlords who do not as a rule engage in agriculture themselves, fleece their tenants of 50-60 per cent. of the total crop. But the Japanese peasantry are forced to carry the burden not only of landlord slavery. To it is added the monstrous yoke of the commercial and usurious capital, their ruthless exploitation by the mortgage banks and monopoly trust companies. In the complexity of these conditions one of the fundamental causes of the constant degradation of Japanese agriculture should be sought, one of the causes of the ever-growing pauperisation of the bulk of the peasantry, and the steady contraction of the home market and the consequent growth of the crisis of the entire national economy.

We shall now pass to the characteristic features of Japanese industry. There is no doubt that Japan has made considerable strides in her industrial development during the past three decades. The coalescence between the banking and industrial capital in the form of gigantic vertical trusts has reached unusually enormous dimensions during the past years. It is a well known fact that 18 monopoly companies control 65 per cent. of the entire national income of the country, and that five of the biggest trusts actually dominate the economic life of the country.

WAR AND JAPANESE DEVELOPMENT.

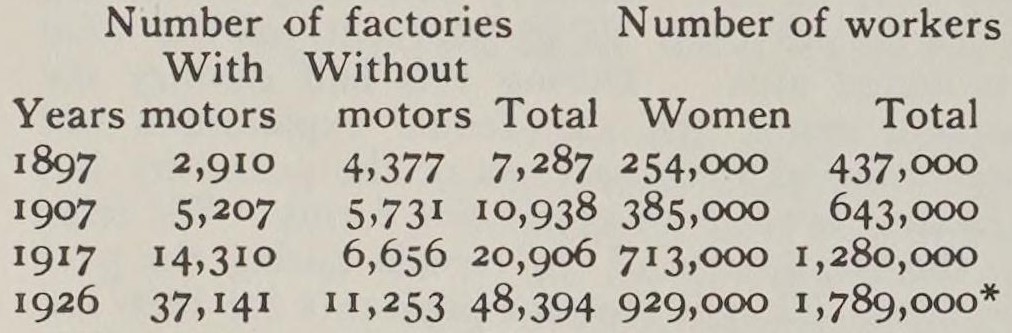

There were a series of factors responsible for the rapid industrial development of Japan, for the enormous accumulation of capital and its centralisation in the hands of a small clique of financial magnates. A special role in this respect has been played by war as a result of which the plunderous Japanese imperialism consolidated its power and captured enormous wealth. The colonial robbery and the trophies of victorious wars waged by Japanese imperialism during the past decades served as one of the principal sources of capitalist accumulation, Japanese industry has always developed by leaps and bounds, the different stages of this development being directly connected with plunderous wars of Japanese imperialism. These leaps of Japanese industry are indicated by the following table:

* To this figure should be added 180,000 workers employed in 380 Government factories, 350,000 miners and about two million non-factory workers.

The years quoted in this table were not selected at random. These were years following directly upon victorious wars in consequence of which capitalist and landlord Japan obtained tremendous indemnities and war trophies. Thus, in 1895, upon defeating China, Japan captured Formoza, annexed Korea and imposed upon China an indemnity of 350 million yen. After the war against Russian tsarism in 1904/1905, Japan seized half of Sakhalin, the leased territories of South Manchuria and the South Manchurian Railway, and received 200 million roubles in the form of payments for the maintenance of prisoners of war. During the years of the world slaughter (in 1915) Japanese imperialism presented China with the famous 21 demands aiming at the complete colonial enslavement of China. During the same years when the economic connections between the imperialist powers and many of the most important countries of the Pacific and of the Near East were weakened and the demand for industrial products tremendously increased, opening up new prospects before Japanese capitalism, Japan experienced a speculative boom. She created new business enterprises with feverish speed, expanding her industries and trade tremendously. But the blows of the post-war crisis of capitalism received by Japan were only the more painful. Indeed, during the subsequent period when the Eastern and European markets were gradually recaptured by the imperialist countries which had dominated them previously, Japan entered a period of stagnation and depression followed by a deep and unprecedented crisis.

We have seen what an unusually important role wars have played in the development of Japanese capitalism. But while gaining on war

Japanese imperialism always lost on peace. This circumstance is due to the fact that the increasing aggressiveness of capitalist-landlord Japan, which runs counter to the plans and schemes of the other imperialist powers could not but meet with their resistance. Indeed, after the war with China in 1895, Japan, under the pressure pf the other powers, including Czarist Russia, was forced to abandon many of her claims. Similarly after the world war, at the Washington Conference of 1922, Japan, on the direct demand of the United States, was forced to evacuate the province of Shantung and withdraw many of her 21 demands. The clash of interests of the imperialist plunderers and the growth of contradictions between them strengthened in turn the aggressiveness of Japanese imperialism. There can be no doubt that the present robber war of Japanese imperialism is directly connected with all the previous stages of its expansion. But it is just as doubtless that Japanese imperialism is aiming to consolidate itself further on the Asiatic continent by this war and prepare for the inevitable new wars between the imperialists for the domination of the Pacific.

Without considering this war situation, or the many feudal relics to which we have referred above, on the basis of which Japanese capitalism has developed, it is impossible to understand its characteristic peculiarities. There are many gaps in the economic situation of Japanese imperialism explaining some of its weaknesses. Particularly noteworthy is its lack of a raw materials base, especially from the point of view of the needs of the war industry. We may further note the predominance of light industry, particularly textiles, and the relative weakness of the metal industry. No less symptomatic is the steady rise of the importance of the war industries; accompanied by the decline of such industries as machine tool construction, for instance, which fell from 10.4 per cent. in 1928 to 8.8. per cent. in 1929. Further, while the centralisation of capital has reached gigantic proportions it does not correspond to the relatively low level of the centralisation of production. From the table quoted above it is easy to see the absolute and very considerable growth of the number of motorless factories during the last decades (from 4,377 in 1897 to 11,253 in 1926).

It is also necessary to take into consideration the fact that Japanese industry has grown upon the crutches of State subsidies and has appropriated enormous State funds.

CONDITION OF LABOUR.

A description of the characteristics of Japanese capitalism would be incomplete without an elucidation of the monstrous forms of the exploitation of the working class and peasantry.

One of the main sources of accumulation of Japanese capital has been the truly monstrous exploitation of the Japanese proletariat and of the bulk of the peasantry. The Japanese working class whose labour productivity is not less than that of European labour, finds itself in the position of colonial labour, represents essentially semislave labour and is subjected to merciless exploitation on the part of Japanese capital. Starvation wages accompanied by a long working day, barrack discipline, indentured contract labour, a lack of social legislation and complete political disfranchisement, these features characterise the position of the Japanese working class. On the other hand, the overwhelming majority of the Japanese peasantry represent essentially semiserfs while agriculture as a whole in its character, resembles the semi-feudal system of any colony.

Japan has not yet completely broken all the feudal relations. The development of capitalism therefore has always clashed with the narrow limits of the home market. Having failed to break down all the feudal barriers in the path of its development, Japanese capital took the path of the utmost utilisation of the relics of the precapitalist relations. Capitalist exploitation has been combined with the robbery of the bulk of the peasantry upon a semi-feudal basis. But the more Japanese capitalism adjusted itself to and utilised these relics of the feudal relations, the more limited did the home market become, the more dependent did it become upon the foreign market, the more powerfully was it prompted on to the road of violent, military expansion of its markets.

Just as in Czarist Russia so in Japan “the newest capitalist imperialism is entangled in a particularly thick mesh of pre-capitalist relations.” In an article entitled “Imperialism and the Split in Socialism,” Lenin wrote:

“In Japan and Russia the monopoly of armed force, vast territories or special facilities for plundering foreigners, China and others partially compensate, partially replace the monopoly of the modern, newest finance capital.”

That is precisely why the imperialist policy practised by the dictatorship of finance capital and of the feudal landlords in Japan resembles the features of Russian imperialism of the “semifeudal type.”

In its present plunderous war against China, Japanese imperialism seeks to utilise its monopoly of military force, its opportunity to rob, in order to realise some of its annexationist dreams. First of all the Japanese landlords and capitalists are seeking through the further robbery of the toiling masses of China to find a solution of the sharp and general economic crisis experienced by Japan. Realising their plans of preparation for the coming imperialist war for a new partition of the world, the Japanese imperialists are seeking in the present war against China to entrench themselves on the Asiatic continent, to secure sources of raw materials, especially for the war industry, and to insert beneath Japanese plunderous, military, feudal imperialism a more solid and firm economic foundation. Further, in the present war against China the Japanese landlords and capitalists are making an attempt to establish a firm barrier between China (becoming revolutionised) and the land of victorious socialism, are seeking to create a spring board for a war against the U.S.S.R. on the one hand, and an offensive against the Chinese Soviets on the other, By their present war action the Japanese imperialists are also attempting to stifle the growing revolutionary movement of the toiling masses in Japan itself, to drown in a wave of chauvinism, to stamp out by a new war the growing revolutionary struggle of the Japanese exploited masses.

However, the robber war of Japanese imperialism does not weaken but, on the contrary, sharpens to the extreme the class antagonisms within the country, does not postpone but, on the contrary, accelerates the revolutionary climax in Japan. There are a number of symptoms testifying to the further and unprecedented development of the revolutionary struggle of the working class and peasantry of Japan.

The growing economic crisis could not but most painfully affect the situation of the working class and of the bulk of the peasantry. The offensive of the Japanese capitalists and landlords upon the already miserable living standards of the workers and peasants caused a growth of ever more resolute mass actions of these against the exploiting classes. The last few years present a picture of the steady rise of the strike movement, of the spread of the economic struggle of the Japanese proletariat from one industry to another. Below is a table based upon official and, therefore, underestimated figures on the number of conflicts between labour and capital and on the number of workers involved in the struggles of recent years:

Year–Number of disputes–Number of persons involved.

1925—816–89,387

1927–1,202–103,350

1928–1,022–101,893

1929–1,420–112,144

1930–2,289–191,805

During 1931 the strike movement gained further momentum. Thus, while during the first half of 1930, 728 strikes took place, involving 76,791 persons, during the same period of 1931 there were 879 strikes, involving 84,344 workers. But what is of still greater importance, during the present imperialist war the strike movement not only has not declined, but on the contrary continues to grow. Thus, between September and December, 1931, there were 842 strikes against 740 during the previous four months.

But the sweep of the strike movement is not only characterised by these purely quantitative data. The duration of the strikes grows, the number of repeated strikes increases, the workers display ever greater determination in the struggle. The economic battles are more and more frequently combined with an expression of political discontent against the Japanese monarchy and the entire bourgeois-landlord Governmental super-structure. Ever more frequently do these strikes lead to bloody street battles between the Japanese workers and the police.

And this despite the ruthless terror which assumed particularly monstrous dimensions just before and during the war of the Japanese imperialists against China. It is sufficient to point out, for instance, that after an order for the arrest of all the revolutionary workers was issued by the Japanese Government on August a6th, 1931, more than 4oo active trade unionists were arrested in Osaka, over 600 in Kobe, 260 in Kioto, etc. On March 3rd, 1932, a general round-up was carried out by 15,000 police in Tokyo resulting in the arrest of 67,000 persons.

To characterise the acuteness of the struggle we shall cite a few examples indicating how strike battles now proceed in Japan. Thus, the one month’s strike (from December 16th, 1931, to January 16th, 1932) of the workers of the Tagi chemical manure factory in the prefecture of Hiogo led during the very first days to a bitter clash with the police in which two workers were killed and 210 thrown into prison. During the strike of the woodworkers in the Akamatsu prefecture 26 workers were arrested. Last February 200 workers were arrested in the Hiogo prefecture during a strike in a leather factory. At the biggest State metal factory, where in January, 1932, the workers protested against discharges and ill-treatment, the police arrested more than 100 people.

In spite of this cruel terror we see not only no decline of the labour movement but on the contrary a growth of the anti-monarchist sentiments, a revolutionisation of ever-growing masses of the Japanese proletariat, a strengthening of the strike struggle, a growth of the anti-war actions of the working class. Even the fragmentary information which reaches us paints a picture of an interrupted development of the struggle of the working masses against the robber war of Japanese imperialism.

Thus, we learn from the newspapers that at the end of September of last year conferences were held by the left-wing mass organisations of the industrial districts of Tokyo and Yokohama, with the metal and chemical workers’ unions at the head, for the purpose of directing the labour struggle in these biggest centres of the war industry into the channels of a mass struggle against the new imperialist war. At the same time was recorded another event when, owing to the arrest of 30 workers, the police succeeded in preventing an anti-war demonstration by the workers of the “Totensi” and “Yamada” silk factories. Further, on October 5th, delegate conferences were held in Tokyo at the tramway park, electrical station, a textile mill, and a tobacco mill, and on October 6th at a light fixtures factory, a metal factory, a musical instrument factory, a rubber mill, a woollen mill, a printing shop and at two labour exchanges, under the following slogans: “Down with the war in Manchuria and Mongolia,” “Hands off Manchuria and China,” “Down with the imperialist Government of Japan,” “Relief for the unemployed to be met from the war Budget,” etc.

The newspapers further report that early in October the workers of the dyeing mill in the town of Wakayama distributed anti-war leaflets. In the prefecture of Oamori shop meetings were held under anti-war slogans at a canning mill, and factory delegate conferences were organised in two factories and three printing shops. In the middle of October a strike broke out at a military aeroplane factory near Tokyo. On November 28th the striking workers of seven Tokyo factories organised, under the leadership of a joint strike committee, a united demonstration under the slogans: “Down with the imperialist war,” “Against dismissals,” etc. On December 12th, at a conference of representatives of twelve glass factories and two unemployed organisations of Tokyo, a resolution was adopted against the imperialist war and in the defence of China and the U.S.S.R. In order to conclude the list of these highly significant signs of the growing struggle of the Japanese workers against the imperialist war we will cite only one more report of the wave of demonstrations against the war and in the defence of China and the U.S.S.R., which swept all the industrial centres of Japan during the anniversary of the October Revolution and which gathered in Tokyo alone more than 2,500 workers.

THE PEASANTRY.

The Japanese peasants, who are subjected to merciless exploitation, are also far from silent. The sharpening of the agrarian crisis and its effects have created the prerequisites for a mass and constantly growing peasant movement. The following table, drawn up on the basis of official data, conveys an idea of the growth of the agrarian disputes during the last few years. The number of such disputes has been as follows:

1928–1,866

1929—1,949

1930–2,109

1931–2,689

It is characteristic that while in the past the majority of the disputes were conducted more or less peaceably, armed clashes have lately become very frequent. We shall cite here also cases of agrarian disputes reported in recent newspapers. Thus, in the middle of January of this year a serious clash occurred between the peasants and the police in the village of Kanagana (in the prefecture of Fukko). This village had up to that time been regarded by the landlords as entirely safe. As a result of this action 94 peasants were arrested and 30 were committed for trial on riot charges. About the same time 600 peasants stormed the court in the prefecture of Niagata, where 22 peasants were being tried, demanding their release. In the middle of January the landlords in the village of Gokamura (in the prefecture of Nagan), fearing the peasants’ action which was being prepared by the Tseno peasant union, themselves released the peasants from 70 per cent. of their rentals. The newspapers further report that in January the peasants of six villages of the prefecture of Koti organised a no-rent union. On January 24th, a bloody battle occurred between the police and the peasants of one of the villages in the prefecture of Nagana, in consequence of which 28 persons were arrested. On February 2nd a peasant meeting was held in the village of Yosima, in the prefecture of Saitama, leading to a clash with the police and the arrest of 12 peasants.

The list of these occurrences could be continued, but even the examples already quoted testify sufficiently to the growing struggle of the Japanese peasant masses, a struggle which is assuming ever sharper and more organised revolutionary forms. The intolerable and unbearable situation of the bulk of the peasantry and their awakening to the active struggle against the landlords and the entire police régime may be judged also by the statement of a representative of the ruling bureaucracy, the former Minister of Finance, Inouye (who has since been killed), who, expressing mortal fear of the coming revolution, stated in February, 1931:

“The peasant masses, which have hitherto served as the most valuable source of exploitation for Japanese capitalism, from which it received its principal weapon in the international competition, cheap labour, are now in a catastrophic situation.”

The peasantry is beginning to take a more and more active part in the anti-war movement. Thus, already on September 17th and 22nd of last year, peasant meetings were held in six villages of the prefecture of Toyama. These meetings adopted resolutions against the imperialist war and the Manchurian intervention. Similar anti-war resolutions were adopted in October, 1931, at a conference of the regional council of the left peasant organisations of the prefecture of Gif. In November of the same year an anti-war meeting was held in the village of Hadboni, in the prefecture of Toyama, in which more than 500 peasants participated. The meeting developed into a regular anti-war demonstration. A clash with the police followed, during which the demonstrators shouted: “When we establish the Soviet Government the police and the monarchists will not be left alive.” On the following day the police released five peasants who had been arrested during the demonstration, owing to fear of a mass attack upon the police. At the same time anti-war demonstrations were held in the villages of Nametawa and Osawano.

THE ARMY.

But the most noteworthy development is the spread of anti-monarchist sentiments among the Japanese army, the beginning of grave fermentation among the masses of soldiers and sailors. It is sufficient to recall the exceptional measures systematically taken by the ruling classes of Japan in order to maintain the prestige, discipline and belligerent spirit in the army, and to compare them with the anti-war actions registered in the Japanese army from the very beginning of the hostilities in China, in order to appreciate the entire importance of these processes. Kajiro Sato, one of the ideologists of Japanese imperialism, discussing the question of the inevitable war between Japan and America, consoled himself by talk of the superiority of the Japanese Army over the American. He referred to the mass desertions from the American Army during the world war, boasting that the Japanese Army did not know of any desertions.

“In the Japanese Army the regimental commander must resign, begging to be relieved of his post, if one or two of his men desert from the ranks,” wrote the Japanese General. The war in China at once produced a new phenomenon in the Japanese Army, the refusal of the soldiers and sailors to fight. No matter how few cases of this kind may have been recorded they are symptomatic and highly significant.

Some of these facts, despite the efforts of the Japanese censorship, reach the press and throw light upon the processes developing in the Japanese Army. Thus in one of the newspapers we read the following:

“In the town of Dagu, in the province of Kiansiando, Korea, anti-war handbills addressed to the 80th regiment quartered in the town were distributed at the beginning of December. The handbills were signed by the League against Imperialism. Immediately after the discovery of the handbills a careful search was made in the barracks and all the handbills found were taken away and destroyed. The authorities had to admit that according to all evidence the handbills were distributed by Japanese, since Koreans are strictly forbidden to enter the barracks. Careful searches and arrests were made throughout the city, particularly in the labour quarters. A few days later the authorities succeeded in unearthing a secret communist organisation in which several officers of the 80th regiment took an active part.”

The impression which this fact created upon the military authorities may be seen from the fact that the press was forbidden to publish any account of this case. It is only known that 70 Japanese and Koreans, including two officers who participated in the organisation, were arrested.

Similar handbills were distributed in the city of Fengtsian. In the province of Kesianda, in the Kimchen county, the newspapers reported another anti-war demonstration.

The press notes that during the struggle for Shanghai several cases were recorded of Japanese soldiers and sailors refusing to fight. Thus, the Chinese newspaper, “Tavan-Pao,” reports that on January 29th more than 200 Japanese soldiers refused to move to the front. They were disarmed and sent back to Japan. On February 11th about 300 soldiers held a meeting in Hongkew. A manifesto was distributed among the soldiers, signed by the revolutionary soldiers’ committee, and urging them to refuse to fight against the Chinese soldiers, to prevent the invasion of China and to conduct agitation in this spirit among the masses of the soldiers. According to the Japanese newspaper, “Nichi-Nichi Shimbun,” the Japanese steamer, Shanghai Maru, which arrived in Shanghai with arms and ammunition, returned to Japan carrying Japanese soldiers aboard who “had become homesick and refused to fight.” The Chinese newspaper, “Eastern Times” reports the refusal of 600 Japanese soldiers to fight, who arrived in Shanghai in February, 1932. On February 20th these soldiers, on orders from the Commander of the Japanese land forces in Shanghai, were disarmed and taken back to Japan in a cruiser, while the Chinese newspaper, “Tavan-Pao,” reports that “more than 100 of them were shot and the rest sent back to Japan.”

The newspaper, “Changchun-Pao,” (we are quoting from comrade Akhmatov’s article “On the Front of the War Upon War,” see the Manchurian Symposium) reports that a Japanese detachment of 300 men dispatched to the Fushun mines in the province of Mukden refused to obey the order and mutinied. General Hondsio had to send a whole brigade to suppress the rebellious soldiers who put up a valiant and determined fight. The battle between the mutineers and the punitive brigade lasted all night until all the mutineers were wiped out. Several meetings in honour of the insurgents were organised in Tokyo.

The following noteworthy facts should also be recorded: In the prefecture of Gif anti-war talks were organised in October with the reservists who passed a resolution refusing to report for provisional mobilisation. Last October, in connection with the mobilisation of a worker in Toyama, a farewell meeting was organised at the station which developed into a demonstration under the slogans: “Down with the imperialist war,” “We demand the immediate withdrawal of the Japanese troops from Manchuria and Mongolia,” “Improve the condition of the soldiers,” “Defend the U.S.S.R.,” “Fight for a worker-peasant Government.” In the Japanese newspaper, “Niyako” we read that the War Ministry was seriously alarmed by reports from Mukden to the effect that “in the parcels sent to the Manchurian Army leaflets were discovered agitating against the war.”

SUMMARY.

It is time to sum up all of these facts of the labour, peasant and soldier movement. We are able to note a definite growth of the revolutionary sentiments, the development of an ever-growing revolutionary struggle against the imperialist war, against the exploiting classes, against the military-police monarchy. The signs of this revolutionary upsurge, the symptoms of the coming Japanese revolution, are becoming evident even to the ruling classes themselves. This may easily be seen from a careful reading of the recently published findings of the Committee of Inquiry into the causes of the radical trends among the students. This committee, which worked under the chairmanship of the Minister of Education, was forced, among other things, to note:

“The extreme difference in the standards of living of the capitalists and workers, the extreme impoverishment of the village, a sharpening of the labour and leasehold disputes, an economic decline of the middle classes, the absence of any prospects of the students finding employment upon graduation, the decay and rottenness among political circles, the discontent with the political situation and the parties, a tendency to achieve one’s aims by united mass actions, a failure to appreciate the essence of communism and its movement.”

When Ministers are forced to draw such conclusions the ground beneath their feet is pretty hot.

But the foreign bourgeois observers are also looking to the future of Japan with increasing alarm. Take for instance, the editorial of the “Peking and Tientsin Times,” published on October 10, 1931. Here we read:

“Should everything end in failure, considering the existence of an ineradicable plague of dangerous thoughts which has infected the Japanese intelligentsia, and remembering the intolerable economic situation of the Japanese peasantry and the condition of industry, the consequences for Japan may be immeasurably dangerous.”

The revolutionary movement is growing in Japan despite the fact that the Japanese social-democrats of all shades and hues are doing their best to keep the masses away from the revolutionary struggle, to preserve and consolidate the military-police monarchy and the entire system of ruthless exploitation of the workers and peasants practised by the Japanese landlords and capitalists. With unblushing impudence the chairman of the social-democratic party, Abe, addressing the congress of his party, “Siakai Minsuto,” in January of this year, did not hesitate to declare:

“I realise that the social-democracy has finally grown into State Socialism. We, Socialists, are supporters of the monarchy.” There is nothing surprising about the fact that in the present war the Japanese social-democracy has taken up an openly imperialist position. It was this party which propounded the theory that Japan is a proletarian country and China a bourgeois country, and that therefore Japan’s war against China is a “people’s” a “socialist” war, etc. Carrying on active agitation and organisation work in favour of the imperialist war the Japanese social-democracy is holding patriotic demonstrations, inciting the Japanese imperialists to a war against the U.S.S.R.

The Communist Party of Japan which took up a correct position in regard to the war has already scored a good many successes in the organisation of the revolutionary struggle of the toiling masses against the imperialist war, against the exploiting classes and the military-police monarchy: But these successes are far from sufficient. The present situation presents exceptionally important tasks for the Japanese Communists. The Communist Party of Japan constitutes a decisive factor. Upon IT depends the further development of the events, upon IT depends the outcome of the growing revolutionary struggle. The Communist Party of Japan will succeed in performing its part only by overcoming its own weaknesses, its lagging behind the growing activity of the masses, only by strengthening its ranks ideologically and organisationally, by extending its still very weak connections with the great masses of the workers, peasants and city poor and leading their struggle.

But the Communist Party of Japan will not be able to rally the toiling millions to its slogans unless it corrects its mistaken policy on the fundamental question, the question of the character and tasks of the coming revolution in Japan. Thus, in the draft of the political theses worked out by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Japan and published in April of last year the character of the future revolution is defined as follows: “The coming Japanese revolution is by its character a proletarian revolution with a great scope of bourgeois-democratic tasks.”

This erroneous definition of the character of the future revolution is directly connected with the underestimation of the tasks of the agrarian revolution, with a failure to appreciate one of the most important peculiarities of the future revolution which consists precisely of the acuteness of the agrarian question, and the necessity of completely smashing the landlord system.

From what we said at the beginning of the article regarding the power of the feudal relics in the country, regarding the landlord slavery, the conclusion must inevitably be drawn that the agrarian question, the struggle of the peasantry under the leadership of the proletariat for the land and against the landlords represents one of the pivots, one of the central tasks of the future revolution in Japan. The underestimation of this factor constitutes a most serious mistake of the Japanese comrades. The Japanese comrades for the same reason are ignoring the revolutionary possibilities of the middle peasantry also and are adhering to the completely mistaken view, which has been refuted by the experience of the movement, that the middle peasantry in Japan is incapable of a revolutionary struggle against the landlords and the existing régime.

On the other hand, in advancing the thesis of the proletarian character of the future revolution the Japanese comrades are displaying an underestimation of the role of the monarchy, this principal bulwark of the political reaction and of all the relics of feudalism in the country, this enemy of the toiling masses of Japan against which the main blow must be directed. The Japanese comrades ignore the absolutist character of the Japanese monarchy and draw the hasty and incorrect conclusion that “the State Power in Japan is in the hands of the bourgeoisie and landlords under the hegemony of financial capital.”

The absolute monarchy which was formed in Japan after the so-called Medsi revolution in 1868 has maintained complete power in all the subsequent years, covering itself up only by pseudoconstitutional forms, but interfering in reality with any limitation of absolutism, with any restriction of the rights and powers of the monarchist bureaucracy. True, the Japanese monarchy which is an historical product of feudalism, formerly based itself upon the landlord class, while now, as a result of the peculiar capitalist development, as a result of the fusion of finance capital with the overwhelming relics of feudalism, it has developed into a bourgeois-landlord monarchy, and is basing itself upon the landlord class on the one hand, and upon the bourgeoisie on the other, thus representing the interests and, carrying out the policies of these two exploiting classes. But this class character of the Japanese monarchy does not in any way remove the question of the independent role played by the monarchist bureaucracy.

Remember what Lenin said about the Russian monarchy: “…The class character of the Czarist monarchy does not in the least lessen the tremendous independence of the Czarist power and of the “bureaucracy” from Nicholas II. down to the last local magistrate. This mistake, the overlooking of the autocracy and monarchy, its reduction to a “pure” rule of the upper classes, was made by the “recallists” in 1908/1909 (see “The Proletarian” supplement to No. 44), by Larin in 1910, and is still being made by certain authors (for instance, M. Alexandrov), and by N. Rykov, who has joined the liquidators.” (Lenin, volume XV., page 304).

The Japanese comrades must ponder seriously these words of Lenin. They must realise that precisely because of the monarchy, is the country still governed by the most reactionary police régime, are the workers and peasants completely disfranchised, and the toiling masses subjected to the most barbarous economic and political oppression. Now particularly, during the plunderous war started by Japanese imperialism, is the role of the monarchist bureaucracy, particularly of the military, its most reactionary and aggressive section, becoming even greater. The Japanese comrades must clearly realise that the future revolution in Japan will be directed primarily against the bourgeois-landlord, military-police monarchy.

What are the basic tasks of the coming stage of the Japanese revolution? They are (1) the overthrow of the monarchy; (2) the liquidation of the landlord system; and (3) the establishment of the seven-hour day and a radical improvement of the situation of the working class. But the revolutionary situation will at once put on the order of the day also the task of merging all the banks into a single national bank, of control over it as well as the big capitalist undertakings, primarily all the concerns and trusts, on the part of the Soviets of Workers, Peasants and Soldiers’ Deputies. The economic dislocation, the oppression and ruthless exploitation by trustified and banking capital will prompt the masses to carry out this measure during the very first days of the Japanese revolution.

The worker-peasant revolution in Japan, upon overthrowing the monarchy and removing all the exploiting classes, including the bourgeoisie, from political power, upon establishing the power of the Soviets and carrying out revolutionary measures, will take up the path of speedy development into a Socialist revolution and transition to the dictatorship of the proletariat. That is why we have the right to define the character of the coming revolution in Japan as bourgeois-democratic, with a tendency towards a speedy development into a Socialist revolution.

In calling the future stage of the Japanese revolution bourgeois-democratic we do not in the least deprecate its tasks and importance. “The struggle of the working class against the capitalist class cannot develop sufficiently widely and end in victory until all the more ancient historical enemies of the proletariat are overthrown.” (Lenin.) A consistent and determined struggle for the tasks of the bourgeois-democratic stage of the revolution will bring about a close alliance between the working class and the peasantry, the capture by the proletariat of the hegemony, this decisive condition of the victory and development of the Japanese revolution.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/vol-9/v09-n07-apr-15-1932-CI-riaz-grn-mfilm.pdf