The Mexican Revolution begins. The most radicalizing international event of the twentieth century for U.S. workers before the Russian Revolution was easily the revolutions in Mexico. The journalism of John Kenneth Turner was an important element in popularizing the struggle, as well as the role of U.S. imperialism in Mexico. Many of those articles appeared, like this one, in International Socialist Review. Turner had a long relationship with the Mexican Revolution, morphing from chronicler to participant, including gun-running and often donned a persona for his journalistic outings.

‘The Revolution in Mexico’ by John Kenneth Turner from the International Socialist Review. Vol. 11 No. 7. January, 1911.

The prophecy of “Barbarous Mexico,” that “Mexico is hurrying toward a revolution in favor of democracy,” has been fulfilled.

If a revolution of the same proportions existed in Spain, in Russia, or in any other European country, as at this moment rages in Mexico, there would be columns and columns about it in the American press, there would be pagewide headlines, there would be special war correspondents—in the field, there would be magazine articles explaining the situation.

As it is, the newspapers consider it of most importance to iterate and reiterate the official pronouncements, that the revolution is over, that the revolutionists are little more than bands of marauding bandits, anyhow, and that the reports of conflict which have leaked through the censorship were grossly exaggerated.

Were it not that a part of the truth has evaded the stifling hand of the censor, chiefly by means of travelers from the interior who have arrived at the American border, were it not that Diaz has failed to control the press of Mexico even as well as he has controlled the press of this country, it would be impossible to guess at this time either the extent or Seriousness of the rebellion. The day the revolution started, Diaz suppressed every independent newspaper in the country, and yet the subsidized papers themselves told more of the truth than did the American press! Even the press of England, which is much farther away from Mexico in the news sense, has so far printed two columns about the uprising to our one!

If the revolution is of no importance, if it does not seriously threaten the Diaz regime, why did the government seize the telegraph wires and prevent the sending of any private messages referring to the situation? Why did it prevent the sending of news messages except messages dictated by itself? Why did it suddenly suppress all the independent papers in the country? Why did it bar out every foreign newspaper containing news of the rebellion? Why did it hold up private mail both entering and leaving the country for days and days? Why did it spend huge sums of money buying up firearms and ammunition in stores in all parts of Mexico? Why are soldiers patrolling the streets of every border town, and of every interior town, as far as we can find out? Why, if it is nothing serious, were not Diaz’s inauguration ceremonies observed in the usual fashion? Why, if there is no revolution in Mexico, did the Federal Government, or at least the state government of Chihuahua, appoint a peace commission to make promises to the rebels and try to induce them to lay down their arms?

That all of these things have been done seems pretty well authenticated. One needs to know nothing more than these things to know that there are some very serious happenings going on in Mexico. Exactly how serious they are, the detailed stories of the fight, we may not know for many weeks. If the government triumphs in the end, we may never know half the story.

Why is there a revolution in Mexico? Not, as some would have us believe, because Mexicans have revolution in their blood. It is rather because they have manhood in their blood, because they are unwilling to be slaves, because they are ruled by a despot and they want democracy, because there is no way to progress under a despotism except through revolution. I am afraid that Americans generally do not approve of revolution any more, no matter what the provocation. Even some socialists will tell you that armed rebellion is out of place in the twentieth century. It is the despotism of Diaz that is out of place in the twentieth century. Free speech, free press, the ballot—these are modern safety valves against armed rebellion. By denying them, Diaz has made revolution inevitable in his country. Hence, for the blood that is now being spilled in Mexico, Diaz and his partners—including his American partners—are entirely to blame.

The immediate cause of this most recent attempt to overthrow the perpetual Mexican autocracy was the persecution of the Anti-Re-electionist party. About a year ago a movement was started to oppose the plans of Diaz to “re-elect” himself as “president” for the eighth time. This movement was entirely peaceful; its program would be considered conservative in this country; its appeal was merely that the people insist that there be an actual election, that they insist on their right to vote, and that they vote for the Anti-Re-electionist ticket, which was headed by Francisco I. Madero. The speakers and the press studiously observed the laws and even refrained from criticising the character or the acts of the “president.”

Nevertheless, as soon as it became evident that the opposition movement would sweep the country, Diaz proceeded to annihilate it. The story of that campaign I have embodied in one of the chapters of my book, “Barbarous Mexico.” Suffice it to say here that it is a story of press suppressions, political imprisonments, banishments, assassinations and massacres, perpetrated by the government to destroy a peaceful popular movement. Madero was among those thrown in jail for “insulting the president,” and when “election day” arrived the “election” was a stupendous farce.

Following the announcement of the “election” of Diaz and Corral, Madero, as soon as he was admitted to bail, issued a statement to the effect that all peaceful avenues for a re-instatement of the constitution had been exhausted except one, that if that one failed, then the people “would know what they must do.”

The one peaceful means referred to was a protest that might be filed with the Mexican congress against a ratification of the election on the grounds of fraud. This protest, backed by the evidence contained in hundreds of affidavits sworn to by thousands of citizens in all parts of the country, specifying the frauds committed, was duly filed in September. Since the Mexican “congress” consists entirely of appointees of Diaz, this step was merely a matter of form. Of course, the petition was denied.

When Madero announced that the people would know what they must do, he meant that they must oppose force with force. Immediately he began plotting and immediately he was compelled to flee to the United States to escape arrest on new charges.

The revolution was set for November 20. So well organized is the political spy system of Diaz that it was impossible to keep this fact from the government, and a week before that date the prisons began filling up with political suspects. For months the government had closely watched the sale of arms, but at great expense and danger thousands of rifles had been smuggled into Mexico and distributed among some of the secret rebel groups. Many of these rifles were seized; thus was a terrible blow inflicted before the appointed day. The loyalty of the army was doubted. Officers who were suspected of being favorable to Madero were transferred from their commands; according to rumor, some of these were summarily shot; it is said that eleven were shot in Mexico City alone. Soldiers who were suspected of disloyalty, notably at Chihuahua, were disarmed.

A dramatic incident exemplifying the activity of the police previous to the appointed day occurred in the city of Puebla on the morning of November 18. The chief of police and a squad of gendarmes surrounded the home of Aquiles Cerdan, a political suspect. Knowing that they would be killed anyway, the inmates of the house gave battle, five heroic women, Cerdan’s wife and four others, standing shoulder to shoulder with the men in the fray. The senora Cerdan shot and killed the chief of police and the invaders, were repulsed. Reinforcements came quickly. Federal troops surrounded the house and a battalion of regulars was even sent from Mexico City. For many hours a fierce battle raged, in which it is said that more than one hundred lives were lost. The revolutionists who were defying the whole Mexican army did not give up until nearly all of them were killed and their last cartridge was gone. Two hundred rifles were taken from the house by the government.

Despite such set-backs, November 19 Madero left San Antonio secretly and crossed into Coahuila, and on the 20th and 21st the people rose in many cities and towns in widely different sections of the country. In the city of Zacatecas, capital of the state of the same name, the government having seized the arms of the revolutionists, an unarmed demonstration took place in the streets, and there was a wholesale massacre by the soldiers.

Near Rio Blanco, scene of the bloody strike of 1907, there was a fierce battle, the details of which are not yet known. During the first days the government poured soldiers into this section.

Battles are reported to have occurred at Torreon, Lerdo, Gomez Palacio, Parral, Acambaro, Puebla, Zacatecas, Orizaba, Cuatro Ciengas, Chihuahua, San Luis Potosi, Camargo, San Andres, Tomosachic, Reynosa, Santa Isabel, Durango, Namaquipa, Cruces, Hermanas, Santa Cruz, Pedernales, Madera, Ahualulco Etzatlan, Cocula, San Martin, Mazapil, Juchipila, Concepcion del Oro, Moyahua, Irapuato, Acultzingo, Valle del Santiago, San Bernardino Contla, San Pedro de las Colonias, Matomoros de la Laguna, and a number of other places. Some of the reported battles undoubtedly did not occur. On the other hand, it is more than probable that a good many battles occurred that were not reported at all. Uprisings were reported from as many as a dozen different states, but nearly all of those mentioned are reported from the states near the American border.

In the battles the rebels were many times reported as being successful. Gomez Palacio, a large town near Torreon, was captured, but the report that Torreon itself was taken seems to be untrue. Cruces, state of Chihuahua, Santa Cruz, state of Tlaxcala, Guerrero, state of Tamaulipas, and several other small towns seem pretty certain to have fallen within the first few days.

At this writing, December 7, by reason of the government’s control of the telegraph, absolutely nothing is known of the southern part of the country. The opposition to the dictator is stronger in the South than in the North. Naturally, it would be expected that the rebellion would be more successful in the South. From Yucatan have come very meagre reports. There was an uprising in Yucatan and it was reported that fifty soldiers were killed and many wounded. Yucatan regularly has several thousand troops to quell disturbances, yet November 28, a regiment of cavalry was hurried away from the capital to reinforce the government troops in the peninsula. A serious revolt in Yucatan might never be heard of until the rebels were in entire control.

In the North the revolution seems to have focused in the state of Chihuahua, a large section of which is absolutely in the hands of the rebels. Here the army of the opposition defies the government, and in several battles has routed strong forces sent to subdue it. In the last days of November General Navarro, at the head of 600 soldiers, made a sally from the city of Chihuahua to engage the revolutionists. He was met at Santa Isabel, where nearly half of his men were killed and he was compelled to flee in disorder back to Chihuahua.

November 29, a body of 150 soldiers, which had sailed from Chihuahua, were met at Pedernales and the whole force was destroyed or captured.

Representatives from an El Paso paper, who penetrated the southwestern part of Chihuahua, reported that they found nine tenths of the people of the farming districts against the government. These people have risen in arms, have taken possession of the Chihuahua-Northwestern railroad and seem to be in absolute possession of a stretch of 150 miles of the road and a large slice of country on each side of it. In these parts they are so strong that the government has so far not dared to penetrate very far into their country.

Indeed, the operations of the Diaz troops in Chihuahua just now seem to be devoted entirely to defending themselves. Big guns have been rushed from Mexico City, fortifications have been erected, trenches dug; Chihuahua, with nearly 5,000 regular soldiers within its limits, is preparing for a siege. So, whatever the situation in other sections of the country, at least in Chihuahua the revolution is not dead.

During the fighting in Chihuahua the whereabouts of Madero himself has been in doubt. It is probable that, after crossing the border from Texas, he found himself unable to effect a junction with rebel forces which he had planned to lead, and was forced back, after a battle near Monclova, into the mountains of Coahuila or Tamaulipas, or possibly back into Texas, though if he is in Texas he is keeping very quiet.

This revolution of the Anti-Re-eléctionist party should not be mistaken for a movement of the Liberal party, many members of which have been subjected to persecution in the United States during recent years. While, as always, the working class will do most of the fighting and endure most of the suffering, the movement is dominated by middle class interests. If Madero wins, his party will undoubtedly free the slaves, ameliorate the condition of the peons, pass a few labor laws, and establish free speech, free press and actual elections. As these things would constitute a tremendous step forward, I, personally, wish the revolution every success, whether, in the end it is dominated by the Liberal party, or, as now, by the Anti-Re-electionists. The Liberal party, would, of course, go farther. The Liberal party would take immediate measures to break up the vast haciendas and give the lands back to the people. It would also rigidly enforce the existing laws against the Catholic church, which it suspects Madero would not do. In my opinion the Mexican Liberal party is as thoroughly a movement of the toilers as is the Socialist party of the United States.

While the leaders of the Liberal party will not endorse Madero or his program, there is little likelihood of there being a clash between the two elements, at least not until after the Diaz regime is overthrown. When the revolution started, the Liberal junta, located in Los Angeles, issued a manifesto setting forth the difference between the two movements, but advising its members to take the opportunity of the Madero rebellion to strike a blow at the government. If the revolution grows the Liberal leaders will throw themselves into it and attempt to dominate it in the interests of the more radical Liberal program.

Will the revolution triumph? It is difficult for the ordinary American to understand the tremendous odds against which these patriots are fighting. The Diaz government is at least ten times as well prepared to cope with insurrection as is the United States. Mexico has a standing army of 40,000, which is three times ours in comparison with the population. Mexico has a force of nearly 10,000 rurales and a tremendous organization of regular and secret police. The capital has 2,000 uniformed policemen—double the number of New York, in comparison with population.

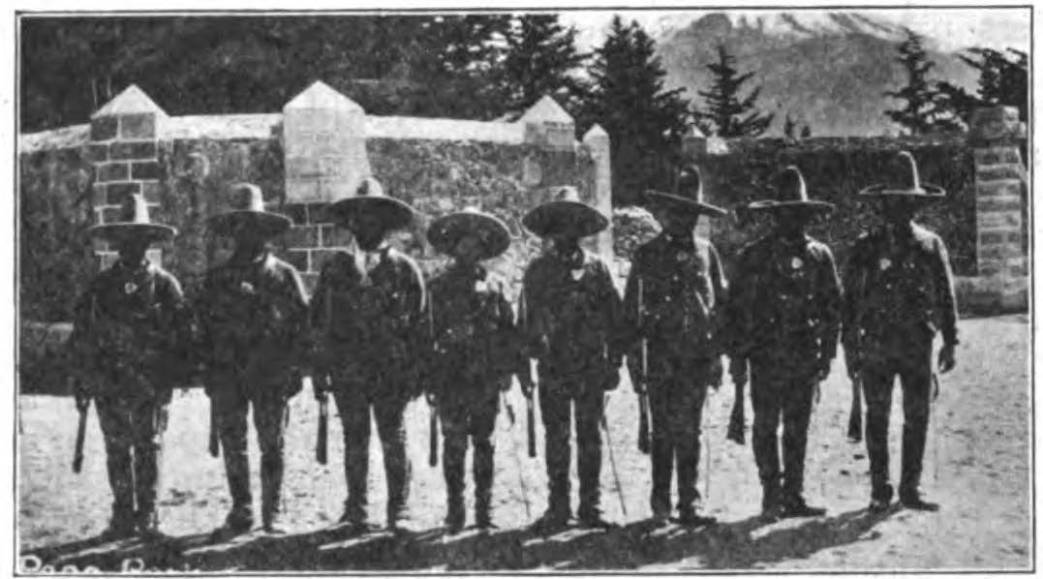

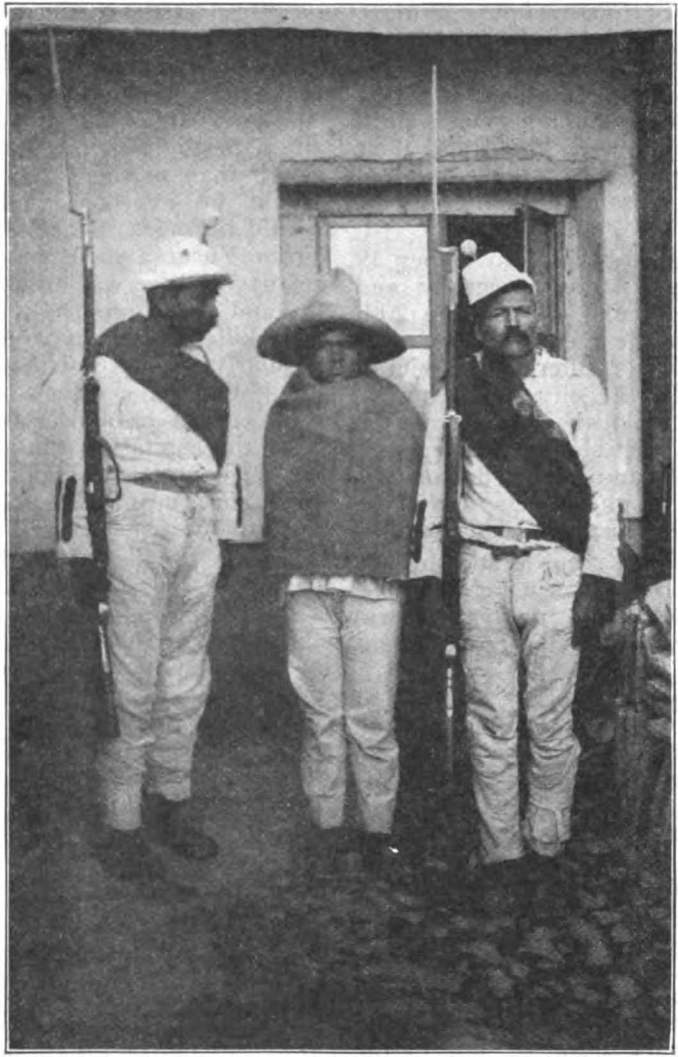

And these soldiers, rurales and police are everywhere. There is not a town of respectable size in all Mexico that has not at least one company of soldiers, as well as its quota of rurales. The barracks are situated in the heart of the city; the discipline of war is kept up at all times. Even the equipment of the army is especially designed with a view to putting down revolt; the Mexican army makes a specialty of mountain batteries, and mountain batteries are most useful in internal warfare.

The strength of the revolution lies in the fact that the people are with it. Were a fair election held, Madero or any other opposition candidate would defeat Diaz ten to one. But majorities do not count in a nation that is ruled by the sword. If the revolution wins, it will probably be only after a desperate struggle in which at least a part of the regular army is won over to the revolutionist cause. Luckily, the army is made up largely of political suspects, labor agitators and workingmen who have been drafted, and they will fight for the purpose of improperly intimidatswords [sic] of their officers are threatening them. Give them a chance for their lives and they will desert, almost to a man. Whatever unreported success the revolution may have at this time, it is certain that the government, in general, has the upper hand; but if the rebel nucleus can be maintained as at present in Chihuahua for a reasonable time, it must mean the serious embarrassment and probable overthrow of the Diaz regime.

This article would not be complete without brief reference to the part the United States government is playing in the Mexican crisis. Hundreds of miles of the Texas, Arizona and New Mexico border are being patrolled by United States troops, ostensibly for the purpose of enforcing the neutrality laws, actually for the purpose of improperly intimidating Mexicans who wish to go home and fight for the freedom of their country.

The exact text of the neutrality law is as follows:

“Every person who, within the territory or jurisdiction of the United States, begins, or sets on foot, or provides or prepares the means for, any military expedition or enterprise, to be carried on from thence against the territory or dominions of any foreign prince or state, or of any colony, district or people, with whom the United States are at peace, shall be deemed guilty of a high misdemeanor, and shall be fined not exceeding $3,000, and imprisoned not more than three years.”

Does this mean that a Mexican may not go home—armed, if he will—to engaged in a movement against the despotism?

Not in the opinion of United States Judge Maxey of Texas, who reviewed some of the cases brought after the uprising of 1908. January 7, 1909, the San Antonio Daily Light and Gazette quoted Judge Maxey as follows:

“If Jose M. Rangel, the defendant, merely went across the river and joined in the fight, he had a perfect right to do so, and I will so tell the jury in my charge. This indictment is not for fighting in a foreign country, but for beginning and setting on foot an expedition in Val Verde county.”

And yet the United States government has persistently prosecuted Mexicans who have done just this thing and no more. When I set forth these points in a public interview some days ago, an official of the State Department took issue with me, declaring that a Mexican has no right to arm himself and cross the line into Mexico. The official must have known that he was not speaking the truth, but made the statement with the distinct purpose of intimidating Mexicans residing in the United States and preventing them from joining the rebel forces. The presence and activity of the troops at the border themselves constitute a threat that is undoubtedly effective. The police of the border towns, too, have been viciously active. A special campaign has been directed against Mexicans. Hundreds have been held up and searched on the streets and hundreds have been jailed for carrying concealed weapons or for vagrancy.

The American authorities are certainly doing their part in helping Diaz crush the movement against him. So far the American troops have remained on this side of the Rio Grande. If the revolution grows it is extremely probable that they will be sent across, ostensibly to protect American lives and property, actually to hold Diaz, the Mexican partner of Wall Street, chief slave-driver of “Barbarous Mexico,” on his throne.

If, under such circumstances, the American people are quiescent, I shall be ashamed that I am an American.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v11n07-jan-1911-ISR-gog-Corn-OCR.pdf