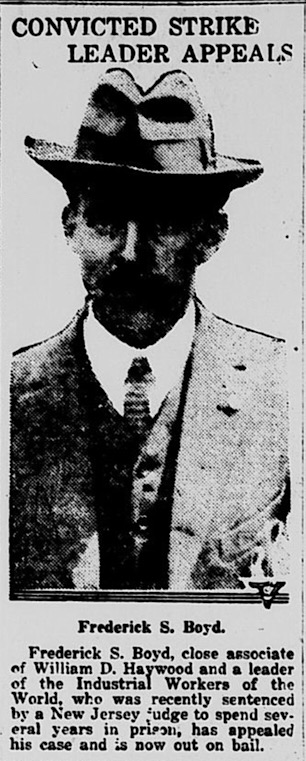

Marine organizing has its own special difficulties; a multiplicity of companies, vastly different legal jurisdictions, multi-national and multi-lingual crews, to name just a few. Frederick Summer Boyd on the strike of tens of thousands of transport workers in 1912.

‘The Atlantic Transport Workers Strike’ by F. Sumner Boyd from The International Socialist Review. Vol. 13 No. 2. August, 1912.

Out of misery and degradation grown unbearable has come another proletarian revolt—the strike of the Atlantic coast transport workers, the strike being called and organized by the comparatively newly-formed National Transport Workers’ Federation, which is industrial in spirit and method, having for one of its moving spirits Jaime Vidal, industrialist and labor organizer.

Upwards of 30,000 workers are already involved in practically every port on the Atlantic coast from Maine to Texas and Cuba. Vidal declares that it is not only for a wage raise that the strike is called, but to organize and protect the transport worker, whether he be sailor, longshoreman, fireman, coal passer, hoisting engineer, waiter, oiler, watertender or checker.

The strike is to some extent a continuation of the general strike last year of the British seamen and transport workers. The British strikers urged their fellows the world over to strike with them, and in response to the appeal the workers this side of the Atlantic quit work. Their own conditions were as bad as those in Britain, and they would have won last year but for the cowardice or treachery of certain “labor leaders.” But conditions remained the same and the fight was merely delayed for a year.

No better accounts of the working conditions can be given than the following from Labor Culture, the official organ of the Federation:

“You, sailors, slaving away for a ridiculous wage under the contemptuous commands of a captain who though himself exploited has no consideration for you, except perhaps when the ship’s in trouble. You, who in cold or wet weather have to be on deck or shin up a mast and often become the plaything of the waves and winds.

“You, cooks, who pass sleepless nights preparing the delicious dishes to be tasted and nibbled at by the over-fed passengers while you are sweating your lives away before the kitchen ovens merely to please those who reap a profit off your work! Your fellow workers aboard the same ship go to bed hungry—or take what they can get out of the “black pan,” warmed over for them, as though they were animals to be fed bones already gnawed at!

“You, stokers, slaving away in those floating hells face to face with red hot furnaces and becoming incapacitated in the prime of your youth because you have chosen to exhaust your health for a petty wage. You, who crawl over heaps of coal in search of fresh air to breathe, often fainting from a lack of it after you had worked overtime under the gibes of your bosses.

“You, stewards, who have to smile and put up with the insults of the chief! You who have to endure the ill temper of the men you serve, having to lower yourself to the doing of things which no steward nor any man should be called upon to do.

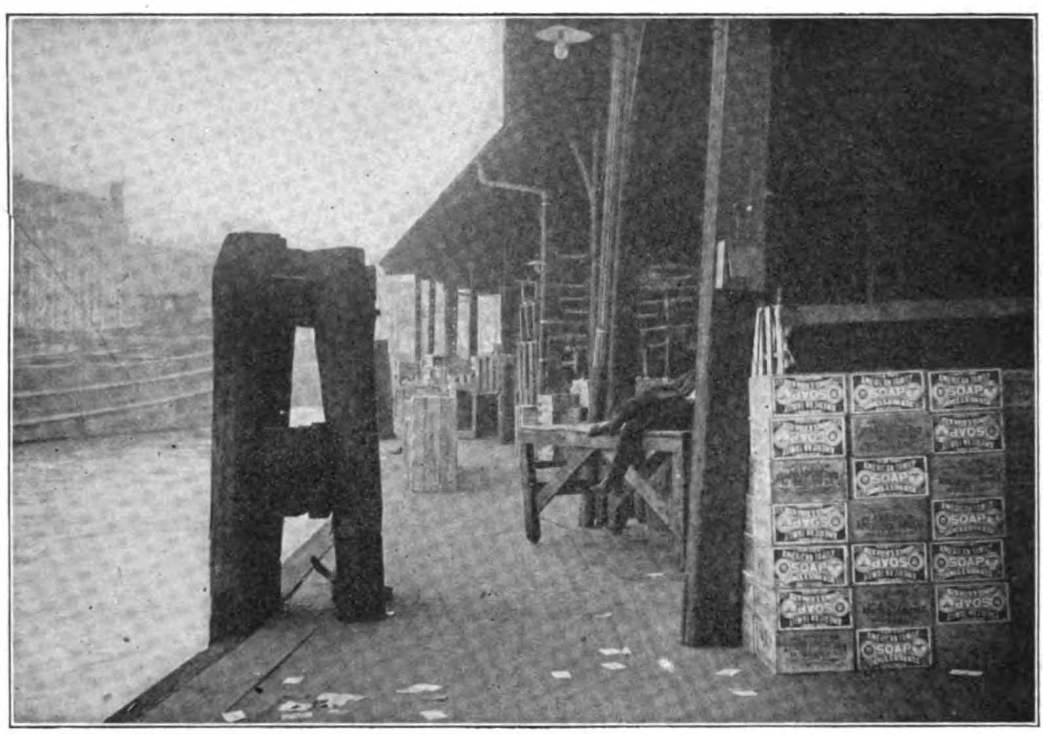

“You, longshoremen, who slave away in the darkness of the warehouses at the risk of being crushed to death under barrels and cases of massive weight. You, whose work is so uncertain and so poorly paid. You who are divided by race prejudice and exploited by your own fellows as well as by your bosses. You who most of all need organization.

“Comrades, unite; for the hour of battle is approaching. Think of the long years of oppression which we have already suffered. It’s about time we were putting an end to it. Let’s burst asunder the chains that bind us! Let’s take advantage of

this golden opportunity! Remember, to be respected these days, we must be united. Then, let us unite! Workers of the World, Unite and Fight!”

Again, M.H. Woolman, in “A Word to You, Longshoreman!” says on June 15: “Over there in Brooklyn the Warehouse Freight Handlers get a miserable wage of 20c an hour. If a ship comes in and he gets through in a couple days, he has earned a dollar or two. And that measley dollar is to last him until there is more work to be done, until another ship comes in! Isn’t that a shame? But who’s to blame. Are not the men themselves? Haven’t they the collective power in their hands to put an end to such capitalist contempt? Five or six hundred men are sometimes at work on one dock, unloading six freight steamers, three on each side and all at once. Then comes the day when they haven’t a thing to do—but ORGANIZE!”

The issue of June 1 under the heading UA Burning Shame,” tells of the abuses heaped upon the marine:

“If the life of the seaman (about which we have had to complain so often) is bad, worse yet is the life of the marine—the man who has to slave away on a collier of the war fleet for a pretty 35 dollars a month.

“Besides that they fine a man ten dollars or more for the merest trifle, as if they were soldiers. In order to get a job on a (collier a fellow has to pay a certain amount, and WHOEVER LATER BALKS AT KEEPING UP THIS GIVING OF PRESENTS IS FIRED.”

To remedy to some extent their vile conditions of work the Longshoremen presented the following demands:

Day work, 7 a.m. to 6 p.m., 35 cents an hour.

Night work, 7 p.m. to 12 a.m., 50 cents an hour.

Night work, 1 a.m. to 6 a.m., 60 cents an hour.

Sunday, 7 a.m. to 6 p.m., 70 cents an hour.

Sunday night, double Sunday rate.

Meal hours (12-1 noon, 6-7 p.m., 12-1 a.m., 6-7 a.m.), 70 cents an hour.

Men working over twenty hours to a finish, to receive last overtime rate.

Fifteen minutes before or after an hour, to call for a half hour.

Men to be hired or knocked off on even time, hour or half hour.

Five minutes to be allowed for putting hatches on.

No bonus or extra pay is to be allowed to gangway men or header.

No timekeeper is to have the power to hire men or blackball them.

No dockmen are to be used to load or discharge lighters for outside contractors, excepting over the side.

No bag stuffs weighing over 100 lbs. to be carried on the docks. Trucks to be used inside when possible.

No case goods to be carried on docks.

The following, taken from the official circular of the Strike Committee, constitute the demands of the maritime unions:

“Shipment of crews by the union. “Four hours on and eight off.

“Sanitary improvements in the sleeping quarters.

“A new bill of fare.

“Also other justified and necessary demands, such as the abolition of the medical examination, and the payment of salaries per trip, etc.”

These demands were presented by the Union of Firemen, the demands presented by the Union of Sailors being analogous, yet adapted to their trade.

The demands were refused by the companies, which include the big Morgan combine, against which the biggest fight is necessarily conducted, and a general strike was ordered, to go into effect at 10 a.m., on June 29.

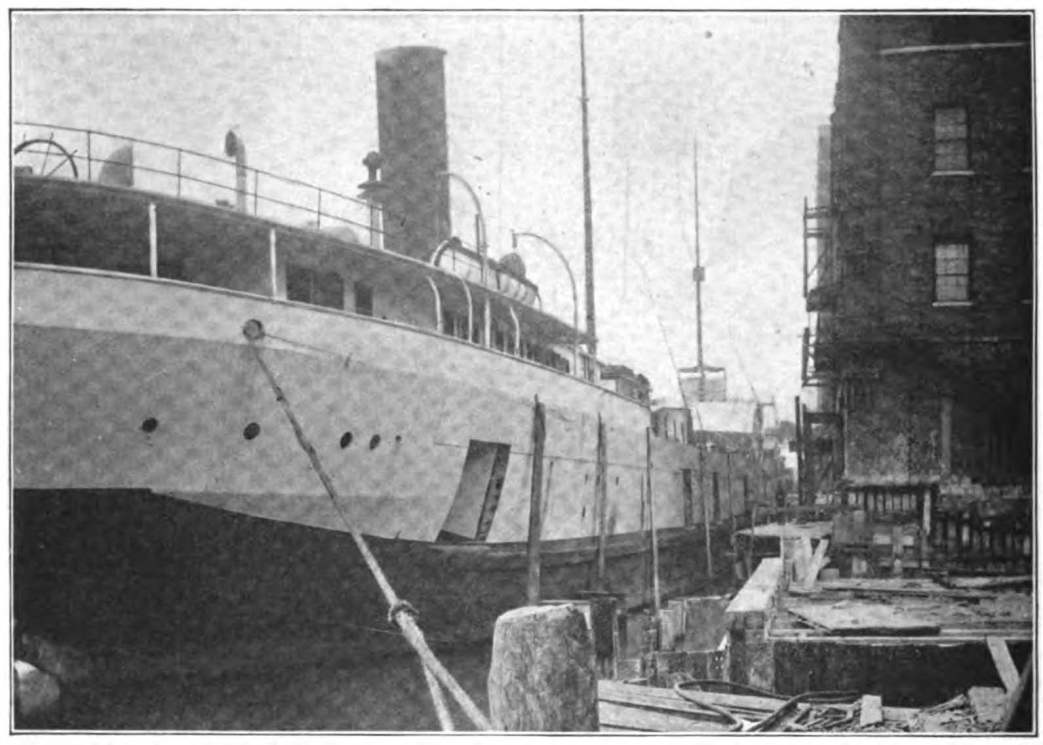

Saturday morning there were to be seen stretched along the waterfront of New York a long line of policemen, on foot and mounted, which served to awaken the interest of the passersby. Even before 10 o’clock the crews of certain ships began to pour forth from the docks of the various companies, among them sailors, firemen and waiters. Everywhere were to be seen the seamen, grips in hand, making for the headquarters of the union. The enthusiasm was great. At 10 o’clock there were no crews left on the American ships in the port of New York. Some English ships were also struck.

At 12 o’clock noon (sailing time for the majority of the ships) some were towed to the Statue of Liberty! Think of that; And there they were stuck, like a stationary fleet of merchant marine, while the companies went everywhere during the afternoon in search of strikebreakers to take the places of the strikers. The purpose of the shipping companies was plain.

They towed their vessels out to the Statue of Liberty because in last year’s strike many of the passengers came back ashore, tired of waiting for the sailing of the ships.

Thus the companies held their passengers prisoners for more than eight hours in front of the Statue of Liberty!

Within a few hours the Strike Committee received telegrams from practically every port on the Atlantic Coast from Maine to Texas and Cuba, stating that ships were tied up and Longshoremen on strike.

The companies, meantime, had been preparing, and had housed scabs in boats along the river, and with these men, incompetent, drunken and vicious, and with the help of the authorities in winking at flagrant acts of peonage, some ships managed to clear New York, many hours late and with a fair chance, of never been seen again save as derelicts.

But the most significant thing in connection with the strike is the use by the government of naval seamen to man the ships of the Panama line, which is government owned. In any considerable battle between the capitalist and the proletariat, such as a general strike of transport workers, the whole of society is affected, and class interests as distinct group interests are at stake. Under these conditions the capitalist class calls to its aid all its forces to crush the revolt of its slaves, and then is seen the true character of the State. The State then proclaims itself by its acts as the representative, not of society, but of a class, the dominant class, today—the capitalist class.

This has been demonstrated in Italy, France, Germany, England, and is now again demonstrated in these United States by the action of the State in compelling United States naval seamen, working men themselves, to scab on their fellows and thus to aid in breaking a strike for better living and working conditions.

The National Transport Workers Federation was formed after the A.F. of L. Atlanta, Ga., convention, when the Waterfront Federation asked that a Transport Workers Department be organized on the lines of the Building Trades Department. Andrew Furuseth of the International

Seamen’s Union, moved that the matter be referred to the Executive Council, which is the A.F. of L. morgue, to which is transferred undesirable motions that it is not polite openly to oppose. The Waterfront Federation then gave way to the Transport Workers Federation, composed, until a little time before the strike, of the following affiliated unions:

Marine Firemen, Oilers and Watertenders of the Atlantic and Gulf.

Atlantic Coast Seamen’s Union.

Marine Coast Seamen’s Union.

Marine Cooks and Stewards Association of the Atlantic and Gulf.

Harbor Boatsmen’s Union of New York and vicinity.

National Sailors’ and Firemen’s Union of Great Britain and Ireland.

General Longshoremen of the Port of New York.

International Longshoremen’s Association.

International Union of Steam Engineers.

The Marine Cooks and Stewards are—or, rather, have been—manipulated by one Henry P. Griffin. When the time arrived to take a ballot of the union membership on the question of a general strike, this A.F. of L. labor leader managed to obstruct so well that no ballot was taken. Continuing to obstruct the taking of a ballot the Transport Workers Federation was obliged to throw out this union a week before the strike was declared, and, although it is probably just what Griffin was playing for, the Federation had no alternative, since it obviously could not continue to be associated with a union that submitted to what it calls “gentlemen’s agreements” between its own and the capitalist bosses.

However, the union members were each sent a circular by the strike committee, urging them to strike with their fellow workers, and at this writing a ballot, initiated by the men themselves, in defiance of their gentlemanly officials, is being taken. It is likely to result in the downfall of another labor leader.

T.V. O’Conner, president of the International Longshoremen’s Association, has also been compelled to display his yellow streak. His “association,” in addition to six locals in New York City, has six locals in Brooklyn, three in Hoboken, one in Jersey City and one in South Amboy. As the strike propaganda grew in enthusiasm and July 1 drew near, when the agreements expired, the locals in Brooklyn, Hoboken, Jersey City and South Amboy withdrew from the Federation and are now scabbing under the protection of the American Federation of Labor. Despite this weakening of the ranks of the workers the strike is spreading daily, and upwards of thirty thousand workers are on the fighting line. The watchword of the Transport Workers Federation is “Workers of the World, Unite and Fight!” and its officials believe with Karl Kautsky that “today the worst enemies of the working class are the pretended friends who encourage craft unions and thus attempt to cut off the skilled trades from the rest of their class.”

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v13n02-aug-1912-ISR-gog-ocr.pdf