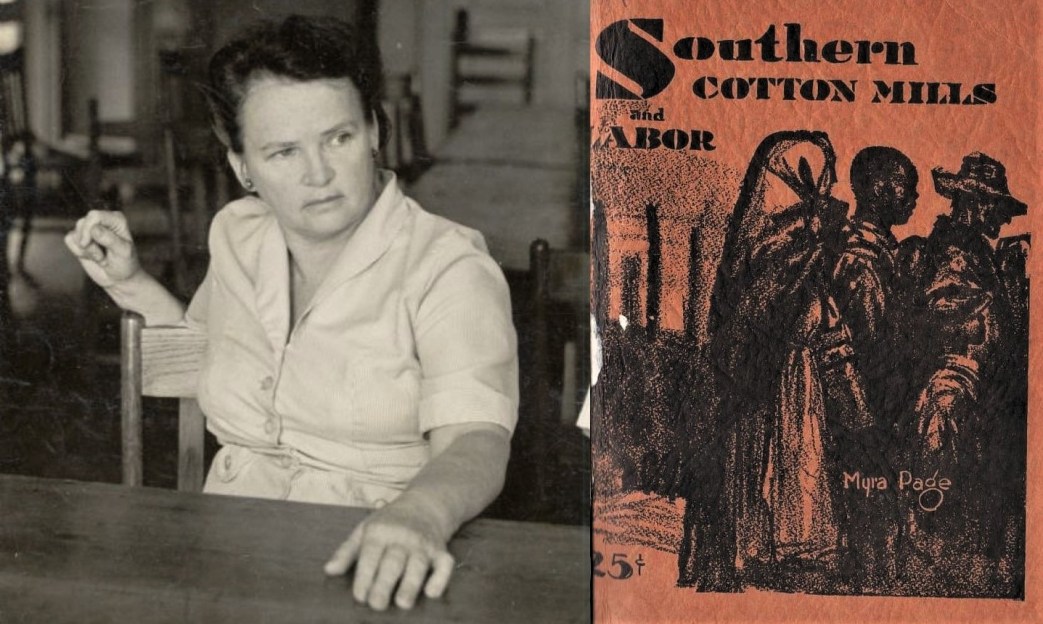

Race was, and is, the central issue around which U.S. politics and its class struggle are waged. Myra Page was born into a progressive, middle class Southern family. Introduced to radicals through the Rand School, including Scott Nearing, she was one of group intellectual women who who became union organizers and Communists, most importantly starting the Labor Research Association. As both her doctoral thesis and work with the movement she investigated emerging Southern industry and conditions among workers in the South. Particularly involved the Gastonia strike of 1929, the Communist Party’s first big campaign in the South, where it confronted that central question in practice. Here, Page writes just as the Party begins to shift its orientation towards Black self-determination in the South as its major focus.

‘Inter-racial Relations Among Southern Workers’ by Myra Page from The Communist. Vol. 9 No. 2. February, 1930.

The Communist Party is assuming, and must assume, a steadily increasing role as leader of mass upheavals in the rapidly industrializing south. Consequently, our program relating to Negro workers and the relations of colored and white labor takes on tremendous significance. The importance of this question is by no means confined to the south, but it does hold especial meaning for us here.

Our Party’s aims and methods concerning these matters were much clarified by the Sixth World Congress, and our general line of procedure worked out. It now remains for us to continue and amplify the analysis of problems and tactics relating to racial factors among the American proletariat, and to train our membership so that correct applications to our policy will be made in concrete situations, as these arise. One very essential task is a thorough analysis of the factors and strategical questions involved in overcoming race prejudice among colored and white workers and poor farmers in the south, A number are entering the south for the first time to do Party or revolutionary union work, and some of these have little knowledge of the character or bases of race prejudice. Therefore they are unprepared for some of the tasks which confront them. On the whole our Party’s recent procedure in dealing with these racial questions has been correct, but at times a dangerous, opportunistic tendency has shown its head— as when Weisbord, then N.T.W. organizer in North Carolina, allowed the lawyer Jimison to “interpret” the union’s program for full racial equality and inter-racial solidarity as “being the same policy as we have always followed in our southern churches.” This gross misconception placed before southern workers was later corrected—but not until the C.E.C. received information on what had taken place. Other opportunistic mistakes could be cited, all of which have sprung from an incorrect understanding on the part of some comrades of the Party line and how it should be applied to the present situation among southern workers. Also, these errors have often resulted from an overestimation of the differences involved, and a shameful retreat before them. It would be a serious mistake, likewise, to underestimate this problem, but in general, the danger is from the other direction.

Our attack on these misconceptions and errors must include a thorough exposition of the historical background of the present racial divisions and antagonisms existing among southern workers, It is obvious that these divisions have had their origin in economic and social conditions, and not in any “innate feelings of antagonism,” as some psychologists would have us believe. Race prejudice first appeared in the “old south” of pre-civil war days, under the economic system of large-scale agriculture, manned by Negro slave labor and dominated by white slave and plantation owners. Besides the two classes of slaves and owners, another class was created by the economic forces of that time—the poor farmers, who tilled a small acreage of rented or highly mortgaged land and owned no slaves.1 Their lot was equally as hard as that of Negro slaves, for while they were “free men,” and could not be bought and sold, and personally maltreated and worked limitless hours as the slaves were; neither were they fed, sheltered and clothed by the slave holders—for the very reason that they were “free labor” and not the personal property of the plantation aristocrats. Their standard of living was often below that of the slaves, which no doubt gave rise to the Negro saying, still current in the south, “I’d ruther be a N***r than a po’ white trash.” The ruling class exploited both their colored slaves and the small farmers.2 The exploitation of this peasant class they accomplished through their role as landlord and extender of credit. Both slaves and poor farmers were kept illiterate, and were the despised and outcast of southern society. The ruling aristocracy gave these agricultural poor derisive nicknames of “Poor Whites,” “No ’Counts,” and “White Trash”—terms which have clung to this day—while the utter contempt which they felt for their slaves was expressed in the term “n***rs.”

Both Negro slaves and Poor Whites despised their exploiters, but unorganized, isolated and backward as they were, and deluged with the master class propaganda on every side, it was natural that the exploited masses of both groups should remain inert. Only the most advanced of the slaves and poor whites dared to protest, but history reports many of these revolts, especially among the slaves.3

However, these were generally spasmodic, local uprisings and in no case joint movements on the part of slaves and white toilers. They were divided from one another by the caste system, and their relation to the economic system of this period was not the same, so that their work and daily life did not draw them together. It was under these circumstances that race prejudice among southern toilers first developed, to be passed on from generation to generation. For the bitterness which the Negro slaves felt toward their white owners was carried over to all whites, since their experiences gave them no reasons for differentiating among them. They had no experiences of inter-racial solidarity, or no knowledge of the possibility of the oppressed of both races uniting in a common struggle against their oppressors. The discontent which the Poor Whites felt against their position the slave-holding aristocracy tried to divert from themselves to the Negro slaves! In this they were partly successful, through their control of pulpit, press and school. The myth of “Anglo-Saxon superiority” which the masters used to justify their subjection of the colored people they now used as a bribe to these Poor Whites, offering them some shreds of “respectability.” The greater economic security of the slaves gave added weight to the growing feeling among Poor Whites that somehow the slaves were partly responsible for the white toilers’ predicament. Looked at from a distance, it is hard for many to see how such a ridiculous idea could gain ground—the slaves held responsible for slavery and their masters’ exploitation of the small farmers as well! Yet even today our comrades will encounter this argument among southern white workers, “But for th’ slaves, we’d never bin Poor Whites.”

It is not a thing of reason, but of insidious emotional conditioning. Like the Negro masses, Poor Whites were isolated, unorganized, and with no other source of information to counteract the ruling class philosophy which dominated southern life. However, the mountaineer section of the White Trash were consistently opposed to slavery and have never been as prejudiced against the slaves.4

The civil war and reconstruction period strengthened the mutual suspicions of Poor White and Negro toilers in the south.

During the conflict, ruling class propaganda along anti-Negro lines became greatly intensified, being used as a means of getting recruits for the southern army. However, Poor Whites were not so easily taken in by this ruse. Large numbers were forced into the southern army but the bulk of them remained indifferent to the planters’ appeals. After the freeing of the slaves many of the southern mountaineers joined the federal army, in order to help destroy slavery and ruin the slave-owning aristocrats. New bitterness was engendered in the complete disintegration of the reconstruction period, which followed the defeat of the southern plantation interests by the northern industrialists. For a short period the old political order was turned upside down; with all whites who had fought in the southern army disfranchised, and the former slaves freed, enfranchised, and in many cases promoted to high political office. (The state of South Carolina, for instance, had a colored governor for a short period). The former slave holders, stripped of economic and political power, once again utilized the race question to mobilize Poor Whites to serve their purposes. This time they were more successful. The extra-legal Ku Klux Klan was formed and used, along with murder, rape, and incendiarism, to terrorize the still unorganized and leaderless Negroes into subjection.

The Negro freedmen soon found that not only southern whites, but northern white men also were now on hand to exploit and betray them. Some of those who came down from the north, it is true, came to give aid, but in general the black man found these newcomers had ulterior purposes. After a few years of “reconstruction,” the northern industrialists and their federal government realized that they had accomplished their aims, having reduced the former ruling class of the south to destitution and made it powerless as an enemy. Furthermore, they saw dangers in the political situation now in the south, and so hastened to act as silent partners in the regaining of political control in the hands of the former southern ruling class. Needless to say, these northern capitalists had nothing but indifference, fear, and contempt for the former slaves, and had only freed them as a politically strategic measure, two full years after the Civil War had broken out.5 The federal authorities now winked at the operation of the Ku Klux Klan, and the adoption of laws in the southern states which again disfranchised the Negroes, by one means or another. So once more the Negroes said among themselves, “No white men kin be trusted. They doan mean no good to us colored people. They’re all for theirselves. When they treat you well, they got an ax to grind.” This tradition of distrust of all whites and holding aloof from them, has been passed down from generation to generation, and still flourishes today. Another saying, which originated in those post-civil war days and still survives, is, that “The white man is all right to deal with, so long as the black man knows his place.” (That is, accepts his role as inferior, exploited, and outcast.) But the willingness to “keep his place” is far less prevalent today, even among the unorganized southern Negroes, than it was at that period.

With the coming of the industrial revolution in the south, beginning the latter half of the nineteenth century, a new situation has developed. The emergence of the southern proletariat, composed of both colored and white, has established the necessary basis for inter-racial solidarity in working class struggle. But until recently this new basis for unity has remained a potential factor, rather than an active one. (Our Party’s entrance into the south marks the opening up of a new era for southern workers, with these factors making for solidarity and struggle organized and given direction.) The old practices and traditions of racial segregation and mutual distrust still flourish, and there are, in addition, actual factors in the present situation making for racial divisions. The capitalists nourish the old racial antagonisms, especially among the Poor White workers, using, as their forbears did, their control of press, pulpit and school to this end. They also use propaganda about “racial purity” and “inferiority of the black race” to build up feelings of superiority in the white workers, while sex fears are played upon until the white population in the south is almost morbid on this subject.6 On the land, in the factories and other places of work, one group has been played against the other. Sections of the more skilled workers, largely white, have been bribed with better (although poor) conditions; and all whites have had the threat over their heads, that colored men will be given their jobs or let into the trade. Furthermore, these workers under capitalism, as long as unorganized and non-class-conscious, are pitted against one another in a mad scramble for jobs, with colored usually forced to underbid whites in order to get work. Colored workers have had access to more types of work here than they have had in other parts of the country, due to the special conditions surrounding the industrial revolution in the south. Consequently, direct competition has been more keen. At the same time, the necessity for joint action has become increasingly more apparent. For wages, hours and working conditions are the worst to be found in the United States. For example, farm laborers and tenant farmers in the south make $24.89 a month and board, or $35.00 without board—just about half of the earnings of agricultural workers in the west or north. (U.S. Department of Agriculture Report for 1928). Wages in textiles, the south’s most important industry, for 1927 averaged $12.80 a week, or about half the average earnings of all wage earners in the United States. Wages for unskilled Negro labor run from a dollar to a dollar and a half a day, and for skilled from two to two and a half dollars. The wages of Negro women and children are the very lowest, ranging from $1.00 to $12.00 a week, with the bulk getting from four to six dollars. These show what the general situation is, where each racial group has been used against the other, to beat down wages.7

Nevertheless, due to capitalist propaganda and their general backwardness, both colored and white workers have not only despised their bosses, but have also blamed toilers of the other race for much of their misery. The A.F. of L. has played a sorry role in this connection, with its capitalist outlook and narrow craft policies. White workers have sought relief through setting up a monopoly on certain types of work. In South Carolina, for instance, there is a law forbidding any but white men to work at the machines in textile mills. White workers refuse, generally, to work alongside a Negro worker, and employers, of course, encourage this segregation. White workers have often entered the Ku Klux Klan, which was revived after the world war, urged on by the fears which obsess them that they will “be dragged down to the level of the blacks.” Driven by this same fear, southern mill workers have told me that “thar is only one mo’ war I’ll fight in, ’n that’s to drive th’ N***rs out of th’ country.” The white workers have formed “white unions,” either excluding Negroes entirely from membership, or merely allowing them in separate locals. Usually the Negroes have simply remained unorganized. Often these unions have been means also of “keeping the n***s in their place.” When Negro locals send delegates to the central labor union, they literally “sit in the back seats,” and take no active part. In some instances a meager cooperation is extended by the white unions to the colored sections, but in general it is a one-way process, with colored workers expected to support the policies and organizations which the whites have initiated and control. Nevertheless, even this very limited type of association shows that there exists a beginning—recognition on the part of both colored and white workers in the south that they must join their forces against the employers. The poor character of their union relations is primarily the fault of the American Federation of Labor, the parent body of these local associations. In practice, it has always assumed the imperialist position toward the Negro as an inferior race of men, whose terrific exploitation was not their concern. The A.F. of L. has officially denied it countenanced discrimination against colored workers, but its record, not only in the south but also in the north and west, disproves its words.

In the face of this general discrimination, not only on the part of white bosses but on the part of white workers as well, the Negro toilers have struggled as best they could. Needless to say, their traditional distrust of white men has not been lessened by their present conditions. But racial consciousness has grown apace. The increasing spirit of revolt was expressed by one southern Negro in these words, “There’s agoin’ to be fewer lynchin’s ’n mo’ riots in this here country. Th’ difference between ’em is this: in a riot, we black men fights back.” Obviously, this racial consciousness offers great possibilities, and also some dangers. It requires direction into constructive, revolutionary channels. The issue must be made clearly one of class against class, never race against race.

The situation between the races in agriculture, in which a majority of the colored toilers in the south are still engaged, has been even more difficult. For besides the negative factors already discussed, of segregation, mutual distrust and lack of organization, there must be added those of the extreme individualism and greater isolation of rural life. Nevertheless, there are dynamic factors in agriculture, also, which can be utilized to draw colored and white tenant farmers and agricultural laborers together, increasing misery and common enemies, of landlord and creditor. But it is in industry and thru the rapid growth of industrial forces of the south that we will make our greatest advance.

It is into this general situation which our party has entered, with its program of inter-racial solidarity of all workers in common struggle for the establishment of militant unionism and better standards of living, for full economic, social and political equality for Negroes, against capitalist speed-up, American imperialism and its war danger and for defense of the Soviet Union. We have begun our task of building the southern section of the Communist Party into a mass organization, through which the vanguard of the Dixie workers, colored and white, in common with the rest of the world proletariat, will lead their fellow workers in their struggles for immediate demands (which today inevitably take on revolutionary significance) on to final emancipation.

It is obvious that our task in the south is not a simple one. However, the dynamics of southern economic life are today of such a character as to assure us increasing headway in bringing together workers of both races on the basis of our program. Our experiences in Gastonia and in other textile and mining centers and the Charlotte conference have demonstrated the correctness of our party line and the readiness of southern workers to follow it. At the same time, we realize that racial prejudices and caste system practices will continue to furnish us with serious problems in our work in the south (and, to a less degree, in other parts of the country). Realistically, we must recognize that as long as capitalism continues its ruling class will do all in its power to foster racial divisions among the workers, at the same time that the main dynamics of economic life and the intensifying class struggle will enable the workers to free themselves more and more from these barriers. A workers’ society is necessary before the old ideological and economic factors can be entirely destroyed and the basis established for full understanding. Race prejudice is one of the curses which systems of exploitation have visited upon the toilers. However, this is not to say that the present situation must continue, where white and black are divided into two hostile camps and pitted against one another by their exploiters. The most advanced section of the proletariat, both colored and white, will be able to free themselves entirely of their former prejudices. These, naturally, will be those who are most class conscious, those who enter the ranks of the Communist Party. In fact, this achievement on their part will be one irrevocable test of their qualification for proletarian leadership, for no chauvinism can be tolerated within the party’s ranks. In this connection it is necessary to keep clearly before us the double objective which we have in our work—the organization and training of the Communist vanguard for mass leadership and the organization of the less advanced masses of workers for revolutionary struggle. These two phases of our work are, of course, vitally related, but it is important that correct attention be given to each phase and to the problems and objectives involved. As far as the question of inter-racial relations is concerned, we will make our best progress, on the one hand, through drawing colored and white workers into common struggle and, on the other, through equipping our southern party members with a thorough theoretical understanding of the revolutionary significance of inter-racial solidarity. Once our southern comrades fully understand the origins, history and working of race prejudice, the harm it has wrought on the toilers of both races and the necessity not only for united action for concrete demands, but also for complete and joint emancipation, once they realize that freeing the proletariat from race divisions is an essential phase of our revolutionary struggle, then these comrades will make the most effective propagandists and leaders of the southern masses along the line of inter-racial solidarity. For they will be able to speak out of their years of experience under this caste system and in phraseology which even the most backward can comprehend. Our party has already made progress in training up such revolutionary leaders from among southern toilers, but this task is so imperative that it demands even greater consideration. Also the attention being given to training of colored comrades from the south should be greatly increased, since objective conditions among the intensely exploited and ostracized Negro masses are most favorable for our work.

For the less advanced, the broad masses of poor white and Negro labor, more and more progress in racial understanding and cooperation will occur. As our party has already demonstrated, these workers can be drawn into joint struggle and into unitary, militant organizations for common objectives—objectives which combine immediate, elementary demands with far-reaching, revolutionary ones. Unions are, of course, our main base for this mass work. Workers will learn, through their actual experiences on the picket line, in mass defiance of police and state force, and in carrying on of union, defense and relief work—what inter-racial solidarity means. A policeman’s club indiscriminately swinging at white and black strikers will do more in an hour to open the workers’ eyes than we might accomplish by other means in two or three months. This is not to say that persistent ideological campaigns are not of prime importance. They are. Southern workers’ experiences must be constantly interpreted and supplemented at union and mass meetings and through the press and workers’ study groups. The problem will require patient and continual work, for at various times points of friction will occur and reactionary tendencies appear, aroused primarily by provocateurs and other agents of the employers. But now that organized struggle is an established fact in the south, the main weight of the bitterness and antagonism which the workers feel can be more and more directed where it rightfully belongs, against the capitalist system and its ruling class.

Our work against this disruptive factor of race prejudice requires also that pamphlets and other literature be prepared, setting forth in simple, direct language the Marxian analysis of this question. Workers must be shown how the ruling class has always used race prejudice in order to “divide and rule,” but that it is the historical mission of the proletariat to smash this caste and class system and establish workers’ and poor farmers’ soviets, in which workers of all races and age groups and of both sexes will work and live on a co-operative equality basis. The accomplishments of the Soviet Union along these lines will prove useful. Furthermore, we must make it clear that if the Negro people desire racial autonomy this shall be realized, just as the Soviet Union has brought about self-governing autonomy for its national and racial minorities. We must be careful, however, both in our literature and daily activities, to keep clear of any opportunistic handling of this question. Racial consciousness is to be utilized only as a means for drawing the toilers of oppressed groups into revolutionary struggle against capitalism, and, in a workers’ society, for furthering these workers’ development toward socialism. It is clearly part of our task to expose such petty bourgeois programs and organizations as that of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, pointing out in concrete fashion how the issue is not one of race against race, but of class against class, with racial factors entering in only as a phase of this class struggle. In this connection, colored workers need to realize more fully that Negro as well as white masters exploited Negro slaves, and Negro employers, creditors and landlords, as well as white, exploit both Negro and white workers.

Our ideological campaigns must also systematically destroy certain myths which have been spread among southern workers through capitalist agencies. One is the myth of racial inferiority of the Negro to the white. This doctrine of “Anglo-Saxon superiority” is widespread among the white population. The shaky evidence on which this myth is based must be examined ani its false character revealed. For our more advanced workers a detailed analysis is necessary. The scientific explanation of the origin of races and the accidental role which race has played in history should be set forth, as well as the materialistic explanations given for the present situation throughout the world, where the dominant imperialist groups happen to be largely of the white race and the subject peoples of the darker race.8 Furthermore, the hypocritical claim of the bourgeois apologists that “the mental tests prove the Negro mentally inferior” must be exposed. Finally, the myth of “instinctive hatred of colored and white” must be utterly destroyed, as well as the various sex fears associated in the minds of many with race equality. The whole question of racial inter-mixture requires a clear presentation, since the current ignorance of southern whites on this matter is as great as the emotional significance which it has for them. This is evidenced by the fact that the first question put by white southerners to anyone advocating political, educational or social equality for the Negroes is, “Would you want to marry a n***r?” or, if the person happens to be a man, “Would you want your sister to marry a n***r?” This is clearly a bourgeois prejudice, yet we have to deal with it among southern workers. In the first place, the confusions and hypocritical assumptions lying back of this statement should be analyzed. A tremendous amount of intermixture has always taken place in the south, and every southerner knows it. This intermixture has been due primarily to the aggressiveness of white males toward Negro women, who usually have been in a position where they could not prevent the advances. Sexual use of colored women slaves by white slave owners and overseers was a recognized practice, and today, while intermarriage is not allowed, intermixture still flourishes. As Communists we oppose the exploitation of Negro and all women for sexual purposes and demand its abolition. At the same time we advocate the removal of all legal restrictions and social censorship of intermarriage. The establishment of personal relations, like those of sex, should be left to the choice of the individuals concerned. In addition to the methods already discussed for breaking down the caste system among southern workers, there are others which ought to be applied more widely than we have done as yet. In union and mass work we can utilize the emotional and other potentialities which music, recreation, sports and dramatic work offer us for welding new bonds of understanding. For example, revolutionary songs and mass singing should be widely developed and used to popularize proletarian philosophy. Since the traditional antagonisms which exist have strong emotional elements, it is necessary to give specific attention to this phase of our activities. As a matter of fact, the American section of the revolutionary movement has generally neglected these forms of creating and expressing working class solidarity. We can learn much from the Russian and German movements in this as in other respects. In all of our activities colored workers should be given every encouragement to assume leadership and take the initiative. This is of vital importance from many standpoints. Also workers of each group should be encouraged to exchange experiences and describe their problems, so that all will see more clearly how similar their difficulties are and how it is the same class which oppresses them all. Under the isolation of the caste system southern toilers are apt to be unaware of these facts. In general, they are simply “n***s” and “poor whites” to each other, not human, flesh-and-blood fellow workers.

The outlook for the revolutionary movement in the south is becoming increasingly favorable. Also our drive against caste system practices and ideology among southern workers has the compelling pressure of modern economic forces behind it. The present-day south offers a striking example of the increasing contradictions of capitalist imperialist and the intensification of the class struggle, with capitalist rationalization and growing pressure on labor on the one hand and the steadily mounting radicalization of the southern proletariat on the other. Due to developments in this revolutionary epoch, Dixie workers will learn with surprising rapidity to destroy racial schisms which have formerly existed and will struggle as a united class for their objectives. Racial prejudice among wage earners has little basis in current economic life. It is largely an inheritance from past economic systems and is now perpetuated primarily by capitalist propaganda and manoeuvers. Every new factory built, every worker drawn into industry, is a blow at the caste system.9 It simply remains for us to recognize and give leadership to the dynamic forces making for inter-racial solidarity of southern workers in the period of fierce class battles which is now opening up.

NOTES

1. The relative sizes of these three classes is estimated as follows: total slave holders in the south prior to civil war, 350,000. Of these, 10,000 were the large-scale producers and owners; Negro slaves, 3,200,000; Poor Whites (small farmers, artisans, workers), 8,000,000.

2. It is worth noting that while the overwhelming majority of the Negroes were slaves, there were Negro freedmen in the slave south, and also Negro owners of Negro slaves.

3. More than thirty revolts took place prior to the civil war.

4. How deep-going and far-reaching the feelings and social tabus of race prejudice are, for both races, perhaps only those who have grown up under a rigid caste system can realize. Both colored and white children are often whipped, scolded and warned against playing and mingling with those of the other race, and lurid stories are told them. Evidence is plentiful that the young do not feel these antagonisms, they have not inherited any antipathy; but their elders, schoolmarms and pastors see to it that they develop them.

5. For a Marxian analysis of events leading up to northern forces issuing of the proclamation, declaring they would “free slaves in those states which would not lay down their arms and submit to the northern army,” see Bimba’s History of the American Working Class” (pp. 113-129). It is necessity for our comrades to become well familiar with this history in order to break the loyalty to the memory of Lincoln and the Republican party, which still has such a hold on the Negro masses.

6. As illustrations of this morbidity: Few southern white women could be located who would venture near a colored section after dark. Needless to say, this superstition has no factual basis. In many mill towns white workers elbow Negroes off the sidewalk into the streets, for daring to intrude into the “white part” of town.

7. Nearing’s Black America contains a wealth of factual material on the economic situation among southern Negroes, and also, to some extent, among southern whites.

8. For further analysis of these questions see D. Gary’s Developing Study of Culture, chapter in “Trends in American Sociology.”—Lundberg, editor.

9. The revolutionary effects of industrial developments on the caste system of India hold lessons for us here.

There are a number of journals with this name in the history of the movement. This The Communist was the main theoretical journal of the Communist Party from 1927 until 1944. Its origins lie with the folding of The Liberator, Soviet Russia Pictorial, and Labor Herald together into Workers Monthly as the new unified Communist Party’s official cultural and discussion magazine in November, 1924. Workers Monthly became The Communist in March ,1927 and was also published monthly. The Communist contains the most thorough archive of the Communist Party’s positions and thinking during its run. The New Masses became the main cultural vehicle for the CP and the Communist, though it began with with more vibrancy and discussion, became increasingly an organ of Comintern and CP program. Over its run the tagline went from “A Theoretical Magazine for the Discussion of Revolutionary Problems” to “A Magazine of the Theory and Practice of Marxism-Leninism” to “A Marxist Magazine Devoted to Advancement of Democratic Thought and Action.” The aesthetic of the journal also changed dramatically over its years. Editors included Earl Browder, Alex Bittelman, Max Bedacht, and Bertram D. Wolfe.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/communist/v09n02-feb-1930-communist.pdf