The so-called ‘Silent Defense’ during the mass trial of dozens of wobblies arrested in Sacramento at the beginning of the First World War is broken as the comrades speak with absolute contempt at their sentencing.

’43 I.W.W.’s Take Their Sentence With a Laugh’ from Truth (Duluth). Vol. 3 No. 6. February 7, 1919.

Defiant Stand of Unionists in Sacramento Told in Eye-Witness’ Account.

An eye-witness’ account of the court room scene when 43 members of the I.W.W. were sentenced in Sacramento 10 days ago, after having maintained a “silence strike against capitalist justice” din, the trial, has just been published by the New York Defense Committee, 27 East Fourth street, New York City. After being out only 70 minutes, the jury brought in a verdict of “guilty as charged” against all of the defendants, showing that the case of each had been dispatched in a minute and a half.

The men seemed rather glad to have it over with, it is reported. There never had been any doubt in their minds as to what the verdict would be. As they were led out of the court room they sang “Solidarity Forever!”

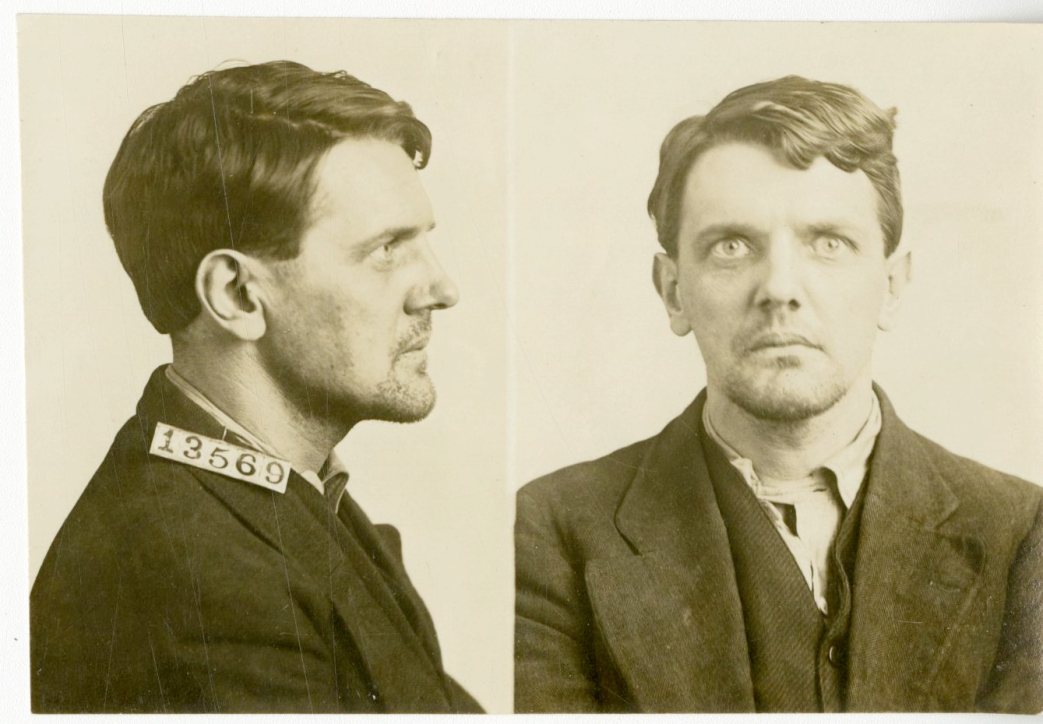

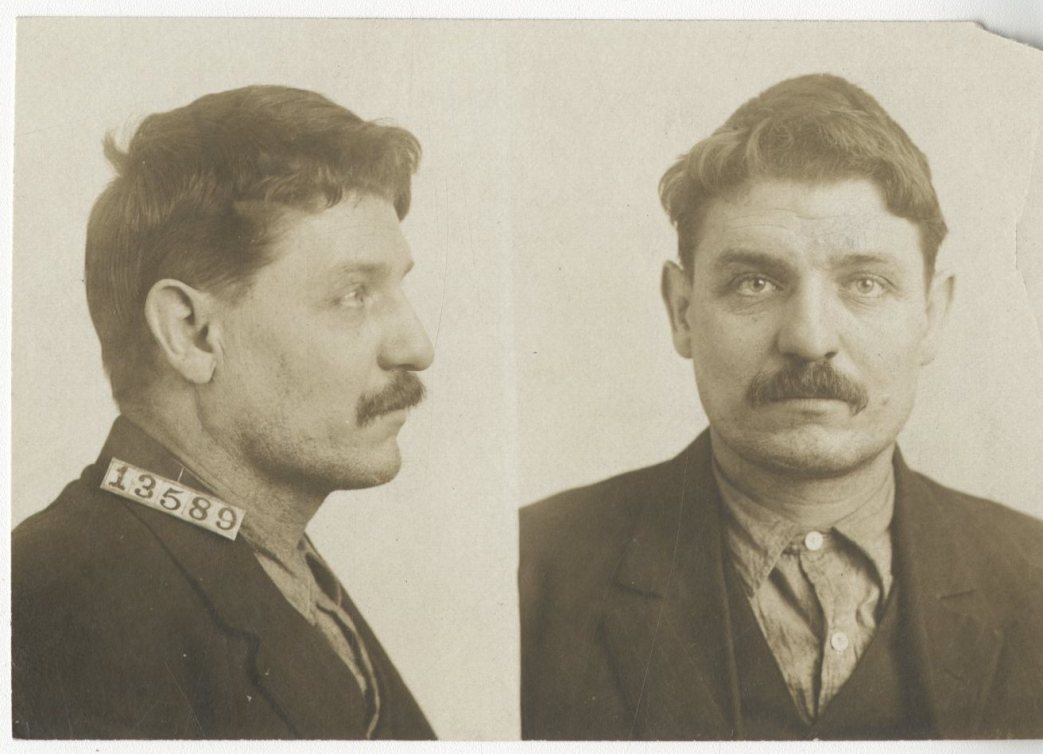

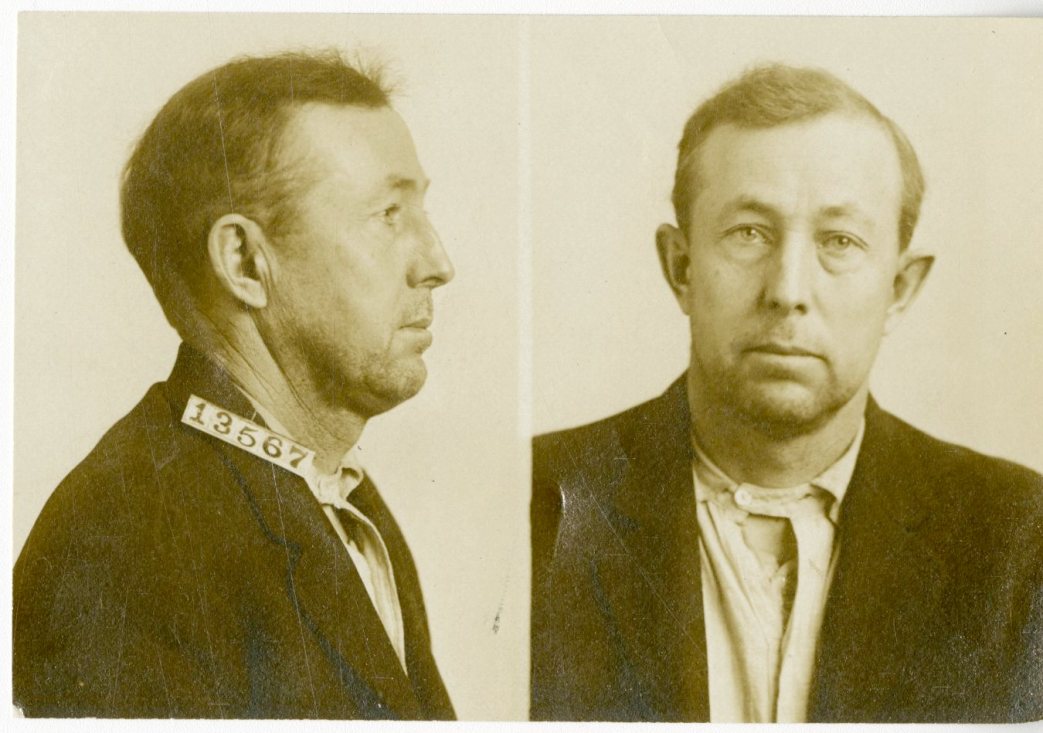

The next morning, January 17, the 43 “silent defendants” were brought in for sentence. The three who had refused to join in their decision to put up no defense were absent. “Have any of the defendants anything to say before I pass sentence?” asked Judge Frank H. Rudkin.

They had, indeed. Their pledge of silence, “in contempt of court,” was to last only until they had been convicted. Their tongues were now loosed. Eleven of them spoke, occupying the entire morning, during which time the 43 stood shoulder to shoulder before the court and delivered probably as seething an arraignment of capitalist justice as has ever been voiced by workingmen.

Through every speech rang the spirit of unflinching defiance, which the men had consistently shown during their 15 months’ imprisonment and their long trial. Not one of them sounded the ingratiating note customary under such circumstances. “Perjurers” was their scornful characterization of the witnesses for the defense and their denunciation of the methods used by the prosecutor was so merciless that finally United States District Attorney Robert Duncan pleaded, “May it please your Honor, I assure you that not one witness I put on the stand perjured himself.”

“The defendants will proceed with what they have to say,” was the judge’s reply.

Mortimer Downing, one of the spokesmen, pointed out that two of the convicted men, W.H. Faust and Felix Cedno, were not even members of the organization in which they were accused of having conspired; that official records showed that defendant O’Connell was in the hospital at the time when one of the government witnesses swore that he had set fire to the building, and that he himself already had been “railroaded” to jail at the time when the government detectives swore that he was out on the picket line in connection with the Wheatland hop pickers strike in 1913.

The evident embarrassment of the government officials at these charges was increased when Downing bitterly arraigned the authorities for forcing a sick man, Frederick Esmond, now believed to be dying of heart disease, complicated with consumption, to sleep on the jail floor without bedding for over two months, along with the other defendants, five of whom died of influenza or pneumonia. “Every employer claims the right to set the hours and wages and conditions under which his men shall work,” said Downing. “Well, I will tell you what we mean by direct action and action on the job. We mean that the worker is going to tell how much and under what conditions he will work. The I.W.W. have taught this, and will continue to teach it, until the workers gradually become stronger and stronger, and finally take over the industries.”

“I am glad I am a member of the I.W.W., whom the District Attorney calls the scum of the earth,” said James Price, another defendant. “At least, I have kept my word and stood by my principles. The District Attorney swore to uphold the laws of the land, but he has violated every principle of the Constitution. When it comes to sabotage, he has the I.W.W. backed clean off the boards.”

In a short, fiery speech defiance, James Mulrooney told the judge why he had become an I.W.W. after witnessing in Butte, Mont., in the summer of 1917, the lynching of a sick man, Frank Little, a member of the executive committee of the organization. He also witnessed the Speculator Mine disaster, when 167 workers were killed.

“I uphold every principle of the I.W.W.,” was his closing challenge. “I am not much of a speaker,” said Frank Elliot, “as I come from the ranks of labor, but I want to express my supreme contempt for the whole gang.” Frederick Esmond, referred to above, made an impassioned address, in which he tore to shreds the testimony of the government, detectives and stool pigeons, denouncing the whole trial as a disgrace to the country.

One short sentence was the speech of Roy P. Connor: “I have nothing but contempt for a court where perjury is considered patriotic.”

Godfrey Ebel told how he had been arrested without a warrant and, when he refused to give perjured testimony against s fellow workers, put in solitary confinement not even being allowed anything to read, and, when his release was ordered by Judge Dooling of San Francisco, re-arrested and thrown into jail along with the others. Will Hood, another of the convicted men, declared that “Dublin Bob” Connellan was imprisoned at the very time when the prosecution’s witness, Bollhorn, had testified to having seen him near a building which he was accused of having fired. Hood’s denunciation of Bollhorn and of the methods used by the government to secure a conviction was so vigorous that the judge finally brought him to a halt.

“We didn’t come here expecting justice,” said Phil McLaughlin. “We want all you will give us. We’ll do the same to you when our turn comes.”

The reading of the sentences was greeted with scornful laughter by the 43 workingmen, more than half of whom, with a smile of contempt on their lips, heard themselves condemned to ten years in prison. They were led back to jail singing:

“Hold the fort, for we are coming. Union men be strong.”

Julius Weinberg, who had turned state’s evidence, was then led forward to make his plea.

“I know these men, your Honor,” he read from his written plea for mercy, “and know the harm that would come to you and me and the United States, if they should achieve their aims.”

The judge let him off with two months in jail. Meanwhile, the 43 men who had stood by their principles could still be heard in the jail tank downstairs, singing “Solidarity Forever.”

Truth emerged from the The Duluth Labor Leader, a weekly English language publication of the Scandinavian local of the Socialist Party in Duluth, Minnesota and began on May Day, 1917 as a Left Wing alternative to the Duluth Labor World. The paper was aligned to both the SP and the IWW leading to the paper being closed down in the first big anti-IWW raids in September, 1917. The paper was reborn as Truth, with the Duluth Scandinavian Socialists joining the Communist Labor Party of America in 1919. Shortly after the editor, Jack Carney, was arrested and convicted of espionage in 1920. Truth continued to publish with a new editor JO Bentall until 1923 as an unofficial paper of the CP.

PDF of full issue: https://www.mnhs.org/newspapers/lccn/sn89081142/1919-02-07/ed-1/seq-1