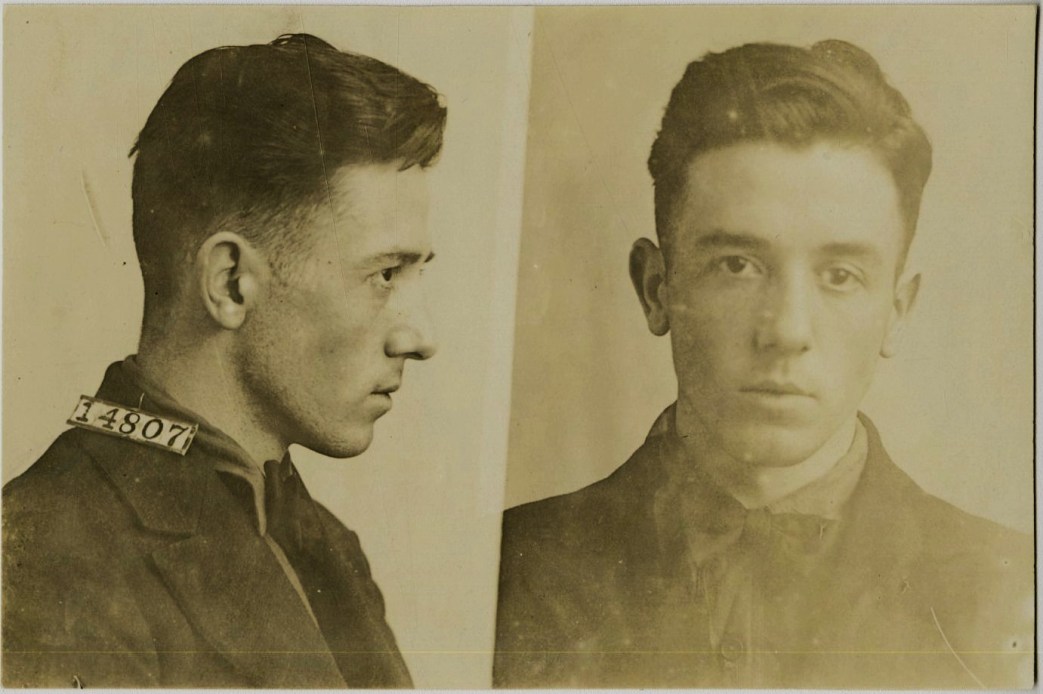

Many legal elements of the large-scale political deportations and imprisonment of the First Red Scare became institutionalized afterwards. Its particular playbook, with accompanying mass racial violence and xenophobia, extra-legal organizations, frame-up, and murder, has been dipped into a number of times since. Leavenworth Penitentiary was a hell where hundreds of conscientious objectors, war resisters, labor leaders, and radicals of all stripes were sent in the crackdown that began with entry into World War One. It became a ‘university of revolution’ in those years. Each prisoner had their own experience. Here is Albert Barr’s. Tarred and feathered in Tulsa by the Klan in 1917, Barr was one of the Kansas wobblies sentenced to federal prison in 1919. An incredibly rich tradition of prisoner solidarity and defense began in that period. A tradition we will need to draw on.

‘Leavenworth’ by Albert Barr from Debs’ Freedom Monthly. Vol. 1 No. 3. October, 1921.

The writer started for Leavenworth from Kansas City, Kansas, wondering whether the well-known Federal prison would be as he had been told it would be, or some otherwise. However, as, sick and trembling, he neared the end of a mile-long walk from the car line with his twenty- five fellow prisoners, and the prison buildings came into view, frigid against a frigid winter sky, his wonderment gave way to relief at the thought that no matter what else Leavenworth would be, it would be a change from the twenty-five stinking, freezing, vermin-infested months of life in Kansas jails–the worst jails in these gloriously free United States.

A short walk from the road–a guard–a gate. A few hurried words–a clash of steel doors and keys and he was in–in–hell.

He was taken to temporary quarters until he had been bathed, de-loused, shaved and clothed. The clothing consists of flesh-rasping, shapeless underwear, rough shoes and socks, coarse, striped shirts, brass-buttoned, gray cotton coat and trousers for winter, and blue overall suits for summer wear. But in all the writer’s eighteen months in Leavenworth he could not escape the feeling that his clothes consisted mainly of numbers; for there are large black numbers stenciled on shirts, caps, coats, trousers, underwear, and in the bottom of all new shoes.

The writer, with most of his fellow prisoners, was assigned to work on the rock gang–known in the prison as Number Three gang–where the main body of the I.W.W. prisoners worked while he was in Leavenworth, and where they still work. Rock breaking in Leavenworth is not the hardest work in the world, considered from the muscular point of view; for the hours are not long and no “task” is set. But he breaks rock today, knowing–how too well–that he will break rock tomorrow, the day after tomorrow, the week after tomorrow, the month after tomorrow, the year after tomorrow. And this ineffable monotony is the essence of Leavenworth.

Almost the only break in the monotony of his days came when he was reported to the Deputy Warden, J. Fletcher, for some real or fancied infraction of the prison rules. And since no one–not the Deputy Warden himself–knows just what the rules are, he was reported not infrequently.

Reported, he was called to the Deputy Warden’s office, where he sat, a stone spider in the stone web of the prison, meting out impartial justice–impartial, because no one ever escapes him. The writer argued with him, cursed him to his teeth–and then received sentence; which is anything from denial of yard and mailing privileges for a few weeks to permanent isolation. Five of the spider’s victims, I.W.W. men, have been in “permanent” for two and one-half years, and will remain there until death or an unjust government releases them. They have all been beckoned by death’s dark hands since they went to “permanent”; and when the first one answers, no one in Leavenworth will be surprised.

But, ignorant and cruel though he is, the Deputy Warden has learned to respect the political–particularly the I.W.W’s.–for they are men, whereas the majority of the other prisoners are just prisoners; society’s misfits, possessing neither courage nor brains.

The chief cause of dissatisfaction in the prison is, understandably, not the work, but the food. Excepting that given the patients in the hospital, all the food is steam cooked, which means that it comes to the table soggy, tasteless and offensive in sight and smell. Much really good food is bought, more is raised on the large prison farm; but after the writer saw the large working force in kitchen and mess hall–“mess” is so expressive of the Leavenworth cuisine–he could find no excuse for the dirtiness and poor preparation of the food. The fact of the filthiness of the food is made plain by the following passage of words overheard at the table:

White Prisoner: “I can’t eat today–I have no appetite.

Colored Prisoner: “Appetite man, you don’t need no appetite to eat here–you needs nerve.

You can read in your glaring cell in Leavenworth; you can study, after a fashion; you can see baseball games and motion picture shows; you can write a few letters a week; yet nightly nearly two thousand men lie down in their cheerless bunks with the feeling that Ralph Chaplin translated so admirably in one line of a recent prison sonnet:

“God, shall we curse or weep.”

Debs Freedom Monthly was published in Chicago to highlight Debs imprisonment, the curtailment of civil rights and free speech, political prisoners, and demand his and others freedom after his jailing in 1919 for sedition. Beginning in August, 1921 and edited by Irwin St. John Tucker, the Monthly carried an eight-point program. After Debs’ early 1922 release the journal was renamed ‘Debs Magazine’ and continued as a vehicle for his writings until 1923, when illness and a contracting Socialist Party closed the magazine.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/debs-magazine/v01n03-oct-1921_Debs.pdf