Ed Falkowski was not just a fine writer, he was an extraordinarily perceptive one. In this wonderful essay, he looks at his own Pennsylvania mining community, exploring the class and social fault-lines between the miners’ families and their ‘learned cousins’, the local teachers.

‘Those Who Educate the Anthracite: Timid Teachers Who Almost Rebelled’ by Edward Falkowski from Labor Age. Vol. 17 No. 1. January, 1928.

I. “WHO IS THIS MAN?”

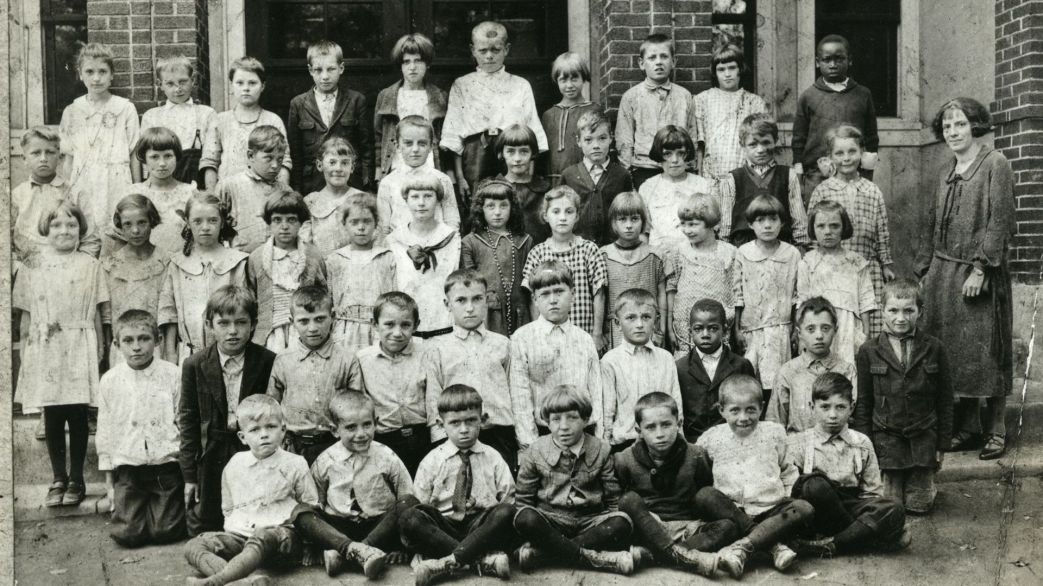

There are more than 200 school teachers in the immediate region of Shenandoah in whose hands the future generations of hard coal diggers are being trusted. Formidable people emerging from middle class-homes to whom the sweat of a miner’s sooty skin is loathsome are engaged in the mass production of American education. Children are so many “heads” to them. The tiny enigmas that grow inside those “heads” are permitted to harden into complexes whose result can be seen in the tough-fibred politician, the frowning pool-room fixture, the slick-haired insurance Valentino, the Charleston cobra and other patterned type that pass on the endless belt of people that live out their destinies in the cracked and pitted undermined country of culm piles and breakers and harsh metallic whistles. Few of these 200 teachers have ever dared to enter a mine. These miners, hundreds of strange, smeared men, whose leather-peaked caps carry battered lamps on them, pass by their homes through the morning fogs in answer to the summons of the colliery whistles. But these teachers never see the world at that hour—never see the miner pounding the pavement and spitting “black marbles” on his way. But when half-past three comes, and the chorus of whistles shouts quitting time, the streets are filled with these black-smocked creatures, many of them dripping wet, stamping the slush off their boots as they walk, and dropping into various saloons for their evening beer.

This dark army of silent men are the anthracite. Their sore backs, swollen hands, blue-marked faces, in which sharp lump etched tales of narrow escapes—often their snail-pace, a mere shuffle with plenty of sit-downs in between—tell something which commission reports and state statistics hardly convey in their interminable legends of figures and technical data, useful only to the expert. But these items of anthracite bureaus that sit on door steps of strange houses to catch their failing breath tell more of hard coal than piles of intricate data, whose deviations tempt students to master the problems which the industry confronts.

Yet to teachers these ragged men are a curious breed whom they cannot understand. Sentiment sprays its tears over them, and strike-periods enlist pedagogical sympathy to the struggling side. But, as these tremendously educated people strut down the streets after the day’s work they never cease to wonder at the miner walking calmly up the street—“Who is this man?”

II. LOWER AND UPPER CRUST

In his home town the miner is the lowest strata of local society. School teachers look with discreet disfavor upon the children of this mucker who must shed his few pints of sweat while he waits for his sons to grow big enough to help him in his struggle for existence. The children of the lumber merchant, the grocer, the saloon keeper, the undertaker, the politician catch warm smiles and intimate attentions. For they are of the upper crust, and will carry on the important work of the universe when they emerge from the educative process. Mining is labelled as a low class of work—degrading, low-paid, dangerous. American history points out vividly how ability percolates upward and reaches its place in the sun here where experts poke long telescopes to the horizon, waiting for genius to show itself. Stories of millionaire grocers, cabin boys who stepped calmly into the immortality of the presidential chair are told over and over again, until the miner’s son regards his sweated father with secret horror, and his daughter aspires to play the piano and take up fancy needle work.

The miner becomes a hopelessly unambitious toiler, blind to the invitation of gilded opportunities. He is a failure in this world where all good things meet with accurate rewards. Business people embody the very spirit of growth and are the spine on whose frame the structure of this national organism depends. The miner drinks. He smokes. He stays out late at nights, and is seen wasting his time playing cards. He never comes to night school. He doesn’t buy lyceum tickets, and fails to attend high school interpretations of stage classics. He yawns in church, and misses days after payday from work. Can one wonder why they will never become foremen, superintendents, stock holders? Not in their path does success lie.

III. MYSTERIOUS UNDERWORLD

Most of the big things in a mining region take place beneath the surface. The smug quiet that surrounds the finer streets, as well as the rattle of Main Street, have only a secondary connection with the life of the miner. Yet the teachers who never touch the elemental things—never walked through miles of darkness so thick one could cut it with a knife—never felt raw drips of water sneaking behind their collars—never dodged the loosened lump as it crashes from above, nor felt the deadening pressure of gas-filled holes, nor ducked the mule’s lifted hoofs—walk through the sunlit slices of earth with their mental trouser belt tightened, their lust for knowledge oozing with smeary phrases borrowed from a thousand authorities.

The underworld is a mystery that fails to arouse energetic curiosity. Eager wonder faints away to a timid shudder as these bloodless creatures consider the hazards of that world whose terrors leap into printed notice which casually tell a bored world that this and this person met his fate today as a rock crushed him to a pulp. Miners read this with a shrug, and turn to the sports. Teachers grin and seek out football scores.

No one is interested in the fate of the humble toiler who walked that very morning in response to the whistles— perhaps whistling himself—full of health and eagerness for work—who now lies in the front room of his panicky family home, a shattered mess of corpse, whose chill face still asks the question it has always asked— “Why?”

IV. THE EMPTY TEACHER

Where being anything other than a mine worker lifts one instantly to higher planes of consideration, the school teacher becomes a being of a higher order and acquires the superior pose. That he himself is pressed down to a mechanical routine, and lacks the rounding out of mature contacts as well as direct experiences of life does not occur to him in its naked significance. He can repeat what he learns which is to him the essence of the teaching process.

He reads Mencken and Cabell—the wicked chorus girls of contemporary letters—and his nose tilts sniffily in disregard of industrial issues. Strikes and tumults of capital and labor are faraway echoes to him, which he regards from the aloofness of historic background. He has no definite opinions, since the cult of Questioners emphasized the cultural importance of losing ourselves in a wilderness of Whys and Wherefores—a road which hardly leads to any Therefores, in the estimation of our learned cousins.

The miners’ union he looks at impersonally—although his own background may have been the humble uprearing of a miner’s son. His interests are above those of labor and unionism. He is a professional worker, and although at a low salary the white collar and the reputation that attends it balances the merely pocket shortcoming.

He is afraid to become a person. A school teacher is a nebulous possibility that never materializes into a full personality. One can almost pass one’s hands through the body, so vaporous and empty is he. He acquires the shape of any vessel he is blown into, and scatters the mist of his insight over the pebbles of small heads before him. Their absorption is the measure of their intelligence. If they are lacking in gray matter, their opposite poles must be appealed to in hope of loosening the brain cells to a proper temperature of receptivity.

V. SUNDAY MANNERS

Yet history secretly records a time when the idea of organization was whispered among them. Low wages, discrimination, political pressures stirred them to protest. Miners’ officials got on the job, hoping to band the teachers into a labor organization. Dim notices of these conspiracies reached the hairy ears of the creaky superintendent, whose religious fires spurted high, and intense indignations poured forth from his office.

The timid teachers wore guilty faces as they felt their economic security slide from under them. The school board roared bulls of protest amid the pounding of the gavel and the wringing of hard fists. The inspirers of youth shook in their patent leather shoes and their hair became disordered as they got wind of this hot fury. They preferred safety first, and dreams of organization quietly faded into the family closets with other dread mementos.

They learned the awful lesson of patriotic duty—devotion to the state, responsibility to the future—and these intellectual boy scouts shivered and their stamina poured out of them like sand out of a torn bag. Since then they have been empty sacks, kicked about left and right by a political school board. Each incoming administration alarms them; they must patronize bosses and live inconspicuous and quiet lives. Their “nice” homes wear the heavy frown of respectability. Their “cozy” furniture is the very perfection of stuffiness. Their Sunday manners have entombed their budding personalities and their lives fade away into endless routine amid ringing of school bells and marking of papers. One sighs to think that beneath this mountain of regimented activity may smolder one whose destiny might have been sharper, clearer cut—whether a cry of agony out of the dark, or a leap of joy springing out of utter happiness of self-realization. But these are only dreams!

VI. TERRIBLE SECRETS

School teachers are no less enigmas to the grim miner, who regards them with a shade of silent contempt. Between them are thin walls of so-called intellect. But the miner has the naked feel of the earth in him. His instincts are fully alive, and he has roots. The pallid teacher is a thin, colorless creature, whose creative wonder is worn away amid the drudgery of every-day discipline and intellectual cowardice. He is a “squib” that sputters out in a fizz that never amounts to more than a squirm and a choking gasp.

But why should it be thus? The teacher must be the mediator between inexperienced youth and the tangled and deep emotions of life. He must introduce curious youth to the profound joy and malice of the universe. It is his task to inspire youth, to seek out the creative spark, the human note, the blind struggling spirit that is seeking roots. This is a task for spiritual heroism, and not mental sneaks who squirm in perpetual degradation, dreading the wet and the cold and the stink that surround a real existence! Give us beauty, give us light—but give us guts and the nausea and rot from which the finer things must spring! Even the most beautiful flowers have their roots in manured mud! We want not mere beauty, but vital beauty! Not mere truth, but living truth. Not only words, but dynamic words.

In the very heart of the anthracite—and of all industries as well—the teacher is one who knows least of life. The patterns of the surface engage them in a gossip of commonplaces. But the so-called artist, living all his life here, has never felt the blinding darkness of a gangway. The business man never felt dooley smoke. The boosters don’t know how it feels to ride down a shaft every morning. Priests know a mine only when they see the outside of it. Newspaper men prefer words to facts. Only the miner knows what the mines are like. His heart burns with their terrible secrets, and the long silences of endless tunnels he carries in his breast.

“Wise” people look at the stern face of the miner and wonder. The miner wonders too—but he doesn’t show it

Labor Age was a left-labor monthly magazine with origins in Socialist Review, journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Published by the Labor Publication Society from 1921-1933 aligned with the League for Industrial Democracy of left-wing trade unionists across industries. During 1929-33 the magazine was affiliated with the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) led by A. J. Muste. James Maurer, Harry W. Laidler, and Louis Budenz were also writers. The orientation of the magazine was industrial unionism, planning, nationalization, and was illustrated with photos and cartoons. With its stress on worker education, social unionism and rank and file activism, it is one of the essential journals of the radical US labor socialist movement of its time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborage/v17n01-jan-1928-LA.pdf