A report on Korea’s 1926 June Tenth Movement, and Communist participation, against Japanese imperialist rule to coincide with the funeral of the last Korean emperor, deposed as a child by Japan’s 1910 invasion.

‘A National Anti-Japanese Demonstration in Korea’ by Kim-Sa-Hom from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 6 No. 58. August 26, 1926.

The last Emperor of Korea, I-Van, who died on April 26th in Seoul, was one of those responsible for the annexation of Korea by the Japanese. It is not surprising that he enjoyed no popularity in Korea. The ingenious notion occurred to the Japanese Government of exploiting his death by preparing a magnificent burial, arranged with the aid of the Japanese police, as a proof to the whole world of the “reconciliation” between the oppressed Koreans and the oppressors, the Japanese Imperialists. They wished to show their concern for the people of Korea and at the same time undertake a further effort towards a reconciliation with the native nobility and a portion of the intellectuals. This plan was frustrated by the Communists and the supporters of the national liberation movement on June 10th by means of a well prepared demonstration about which the Japanese police were fully informed and against which they used every means in their power, including arrest and maltreatment. That is the form which the reconciliation took. Since the revolutionary events of March 1919 and the defeat which the liberation movement then suffered, this demonstration is the first publication of the National Party now in course of formation. It is a turning point.

We have already mentioned the fact that the death of the ex-emperor was to have been exploited for certain purposes by the Japanese Imperialists. As a matter of fact, however, it was the signal for a general offensive of the nationally and economically oppressed broad masses of Korea. Immediately the news of the death spread, two organisations formed and declared national mourning. The Japanese General Governor sounded the alarm in the fear that the long suppressed hatred would find expression in overt anti-Japanese actions. Arrests were made throughout the country. The exact number of the arrests is not known, but is appears probable from report to hand that many thousands were arrested.

The national mourning was observed also by the students, who, in response to the reprisals of the Japanese and Japanophile teachers began a strike which led to fresh arrests.

How bitter the feeling of the population of Korea was, and still is, can be judged by the fact that a Korean planned to assassinate the General Governor Saito, though he mistook for him the president of the Korean branch of the Japanese Fascist Society, Takayama, whom he killed. In addition he wounded Sato, one of the presiding members of the Korean-Japanese Company. The Japanese Fascists replied to the assassination with an armed demonstration and this further gave rise to counter-action on the part of the journalists and lawyers of Korea. They protested to the Japanese Government against the attitude of the Fascists and succeeded in getting the order passed to the Fascists to keep in the background. The reprisals of the police, however, continued throughout May and June.

One week before the demonstration, the Japanese police captured a great part of the Communist proclamations, which were being printed in an illegal printing-works, and as a result many Communists and members of the Communist Youth were arrested. Still, about 50,000 proclamations were distributed to explain to the population the purpose of the demonstration and the slogans used.

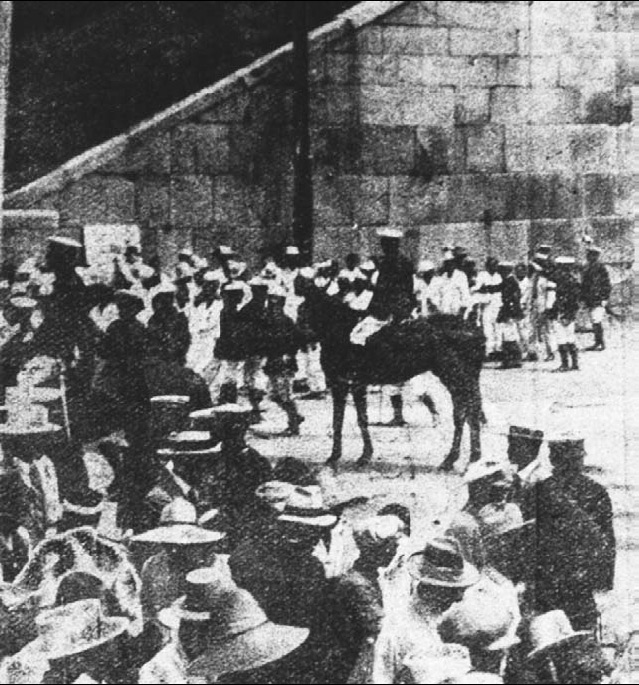

The whole of the Japanese police force was gathered at the funeral to protect it from the demonstrators. This, was, however, not accomplished. The storm troops of the demonstration, armed with leaflets, got into the funeral procession. When a certain signal was given the leaflets were distributed. The cry arose: “Down with the Japanese Imperialists! Set the political prisoners free! Withdraw the Japanese troops and police! We demand the rights of a free people!” Addresses were given by speakers shouldered by the crowd, and, according to the whole of the Korean Press, they got a most sympathetic hearing from the masses. The crowds protected the speakers from the detectives who wished to arrest them.

At the same time as the political demonstration in Seoul, official processions were also held in other big towns, and at these too, hand-bills were distributed. During the funeral in Soul more than 200 arrests were made by the police.

The Japanese police, who fully recognise the significance of the existence of a closely knit Communist Party organisation for the further development of the national liberation movement in Korea, spread the report through the newspapers that the Communist Party had been completely dissolved and that it would never be formed again, etc. They further endeavoured to represent the demonstration as a purely Communist affair, in order to create a split between the Communists and the intellectuals of the national revolutionaries. They will be successful in neither of these things.

The demonstration proved that the movement has reached an advanced stage of development, that the Communists are well established among the masses of the workers and the peasants and that all the supporters of the national liberation movement are co-operating in common actions along an unbroken national-revolutionary front. It further shows that the illusions, upon which the action of the year 1919 was based and which consisted of relying on the support of Wilson and hoping for the liberation of Korea by the Conference of Versailles, have now completely disappeared.

The necessary circumstances for a revolutionary movement in Korea are provided by the social-political relations which have been created by the Japanese forces of occupation: The economic development of Korea has led to the formation of a young native working class, which is being exploited according to the time-honoured colonial system. The position of the Korean workers is indescribable. They have a working day of 10 to 13 hours, and there are absolutely no holidays and no safety contrivances.

The position of the peasants is even worse. About 77% of them have very little or no land at all of their own. They are compelled to lease from the Japanese land-owners and the big stock-company concerns the land of which latter have robbed them. More than half of the arable land is in the hands of Japanese. The rent amounts to 60% to 70% of the harvest. In addition to this the farmers have to submit to a tremendous burden of taxation, compulsory enlistment in public service, the raids of the usurers and, in many cases, unpaid labour for the land-owner.

It must further be stated that the intellectuals and the petty bourgeoisie also suffer severely under the political and cultural oppression exercised by the Japanese. Even in the schools and in the various public the Japanese carry out their programme ruthlessly.

The most active elements in the struggle of the working masses of Korea are the workers and the farmers, who in 1925 organised a total of 300 actions, in which 91,000 farming families took part. The organising of the workers is also greatly advanced. Upon the initiative of the Communists the so-called Workers’ and Peasants’ Congress of Korea was held in April 1925 and attended by the various Women’s and Youth organisations, as well as by representatives of socialistic circles. The weakness of the Korean revolutionary movement lies in the numerous political factions and the fact that they are but loosely in touch with the masses. To this cause must be attributed the recent growth of the terrorist movement.

The left wing of the national-revolutionary movement has been trying hard during the past year to do away with the factions and combine the available strength. There arose the young Communist Party, which has already been recognised by the C.I. and whose vital force has been shown on several occasions, including the demonstration of June 10th. The other groups in sympathy with the C.I. will no doubt consolidate in the course of the fight and form a united left wing. The fact is a very important one that through this demonstration the ground has been prepared for a broad mass movement, not, of course, under the leadership of the Communist party, but under the banner of the national liberation movement and under the leadership of the revolutionary intellectuals. The Korean Communists must do their best to promote the formation of this organisation.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly. Inprecorr is an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1926/v06n58-aug-26-1926-Inprecor.pdf