Gramsci writes on Italian Fascism’s attempts at creating fascist labor unions and their relationship with the country’s industrialists.

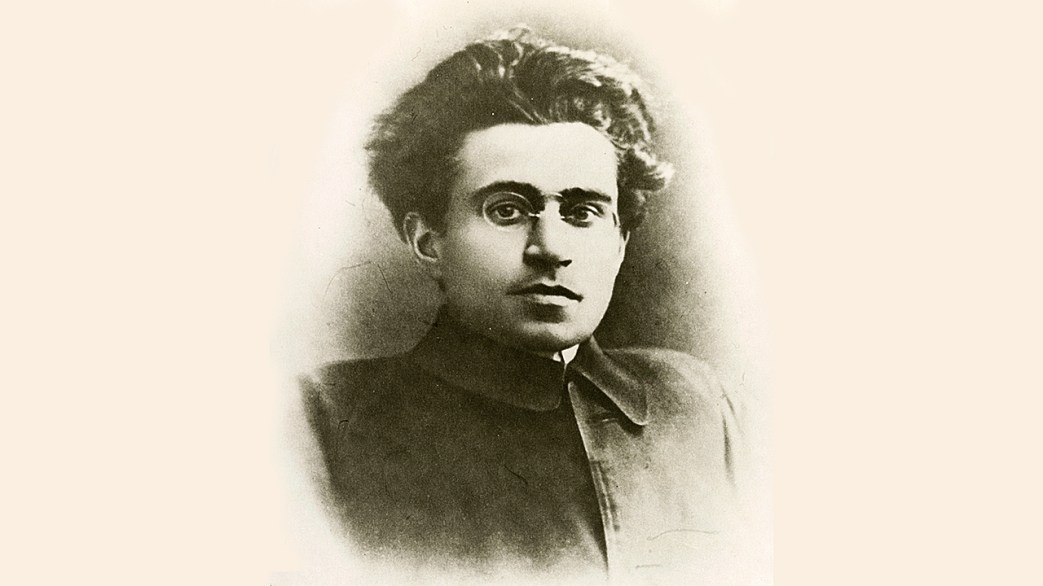

‘Letter from Italy’ by G. Masci (Antonio Gramsci) from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 4 No. 1. January 4, 1924.

At the Conference held on the 19th December under the direct auspices and in the presence of the Prime Minister Mussolini, between the leaders of Italian industry and the principal leaders of the Fascist Trade Unions, the complete failure of the programs and the practice of Fascism in the spheres of Trade Unionism had to be recognized.

The feverish attempts made by Fascism, before and after having obtained power, in order to create a trade union movement which would be at its service, are well known. It is also known, how these attempts, while succeeding to a rather considerable degree in the agrarian field, have failed almost completely in the industrial sphere. It was easy for the Fascisti, in view of the life and working conditions of the poor peasants, and of the rural workers dispersed in a great number of villages with feeble ties between the Trade Unions, to destroy the Socialist organizations of the land workers and to force the rural masses by means of physical terror and of the economic boycott, to enter into their corporations. It was otherwise in the industrial sphere, except with the railway employees, amongst whom much can be obtained by state coercion and by the ever threatening menace of discharge, and also with the dockers who had already their strictly guild-like organization determined by the conditions in the traffic at the Italian ports which is developing very spasmodically, in relation to the preponderance of exports and imports and to the seasonal activities for grain, coals and coffee.

In the large industrial towns, the Fascists only succeeded in gathering inconsiderable groups, consisting nearly everywhere of unemployed and of criminal elements, who, by means of the Fascist party ticket obtain impunity for sabotage, theft in workshops and personal violence against foremen. And yet it was necessary for Fascist politics to win the masses at any price.

The Fascist Government can only maintain power for any time so for as it renders life impossible to other organizations which are not Fascist. Mussolini bases his power on large strata of the petty bourgeoisie, which (since they have no function in the productive life and hence do not feel the antagonisms and the contradictions resulting from it), in fact believe the class struggle to be a diabolical invention of the socialists and communists. The entire so-called hierarchic conception of Fascism is dependent upon that fact. It is indispensable for this conception that no independent organization of a typical class character exist and that the modern social life be organized in a series of petty corporations subject to and controlled by the Fascist elite, being the concentrated expression of all the prejudices and utopian visions of the petty bourgeoisie. Hence the necessity for Integral Trade Unionism, which is a revised conception of the Christian democratic Trade Unionism, substituting the deified nation for the religious idea.

This program was resolutely opposed by the industrials, who refused to enter the Fascist corporations, viz. to allow themselves to be controlled by Rossoni and his like. The Fascists, some months ago, in face of the repulses by the industrials, began a demagogic fight, which went so far as to their announcing and propagating in great style a general strike of the metallurgical and textile workers. The campaign against the industrials culminated immediately after the visit paid by Mussolini to the Fiat works of Turin on the anniversary of the Fascist “March on Rome”. The workers of the Fiat, six or seven thousand of whom had been gathered in the courtyard of the factory in order to hear a speech by Mussolini, received the leader of the Fascists in a hostile manner. The Fascists accused the Turin industrials of having fostered the anti-Fascist spirit of the masses, of preferring to treat with reformist organizations instead of with Fascist ones, of discharging from the Works the Fascist workers, thus preventing the development of the Corporations and so on; they went so far as to attack personally in a coffee-house the chief of the Fiat, Senator Giovanni Agnelli. The situation became very serious for the industrials as well as for the Government. The Communist Trade Unions Committee intervened in the agitation, inviting the working masses to take part in the struggle against the industrials in order to enlarge the movement, even though the struggle had been engaged in by the Fascists. The agitation was stifled by the central leaders of the Fascisti, and the Conference held on the 19th of December was convened. In the speech Mussolini delivered there, he recognized, that it is impossible to organize workers and industrials in one and the same trade union. Integral Trade Unionism, according to Mussolini may be applied, only in the sphere of agrarian production. The Fascists have to respect the organizatory independence of the industrials and have to work only in order to avoid the outbreak of class conflicts. The meaning of these words is clear. The Fascists abandon even the keeping up of the appearance, not only of a struggle against the industrials, but also of any attempt to equilibrate, under their arbitrary control, the interests of the classes and they have only the confessed task of organizing the workers in order to surrender them to the capitalists bound hand and foot. This is the beginning of the end of the Fascist Trade Unionism. Immediately after the Conference, many land owners protested loudly against the discriminating treatment shown by Fascism to industry and to agriculture. They denounced the violence which they said the Fascist Trade Union Organizers exercised to the detriment of the owners’ interests, by compelling them to respect labour contracts, which of course they declare to be absurd and opposed to the interests of the nation, and they claim to be allowed to reconstitute the General Confederation of Agriculture which had been absorbed by the Fascist corporations. At Parma the agrarians have placed themselves in direct opposition to Fascism, provoking a whole series of incidents and conflicts. At Reggio Emilia, the deputy Corgini, former Under-Secretary of State to the Government of Mussolini, has been expelled from the Fasci and leads a raging campaign in favour of the organizatory independence of the land owners.

It is to be remarked how great a success was obtained by the tactics applied by our Party, in order to unmask before the masses the Fascist Trade Unions Leaders who had raised such a hub hub against the industrialists. It is true, these tactics procured to the Fascists the satisfaction of having meetings attended by many thousands of workers, but they led also to forcing the Fascists to the wall, to causing them to eat their words and to discrediting them even in the eyes of the most backward portion of the working masses. If these tactics were generalized and also extended to the agrarian field, it would be possible to accelerate in a high degree the disintegration of Fascism and hence the reorganization of the revolutionary forces. But against this there are the reformist socialists, as well as the maximalist socialists who still have control over the Trade Union Centrals and of the only periodicals of a proletarian character still published in Italy. Thus they demonstrate yet once more that they do not really intend to fight against Fascism. It is true, they risk much if they want to attack Fascism in order to contend with it, within its own Trade Unions or in the agitations sometimes got up by it, for control and leadership of the masses entering the movement. On the other hand, it is certain that large strata, not only of rural workers, but also of factory workers who have no other chance of fighting against the bourgeoisie are drawn to these agitations by the Fascist demagogy, hoping thus to wring something from their employers. The intransigeance shown by the reformist and maximalist gentry, is in fact no intransigeance against Fascism, but against the poorest and most backward portion of the workers. Moreover, it is never true to itself and makes many concessions to the Fascistsi who are governing.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly. Inprecorr is an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: