Jobs our parents relied on to raise us are gone, as are those their parents relied on. The modern working class has constantly been confronted by technologies which could make work easier, but makes jobs disappear. The once proud stenographer replaced by a dictating machine.

‘Modern Office Machinery’ by James E. Griffiths from The International Socialist Review. Vol. 14 No. 10. April, 1914.

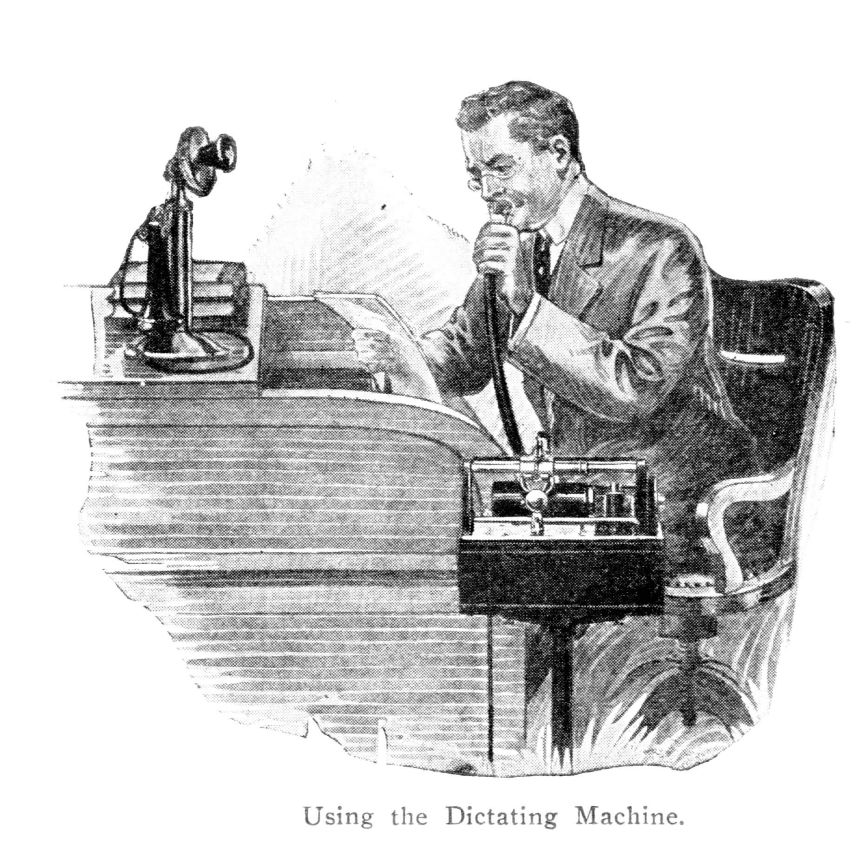

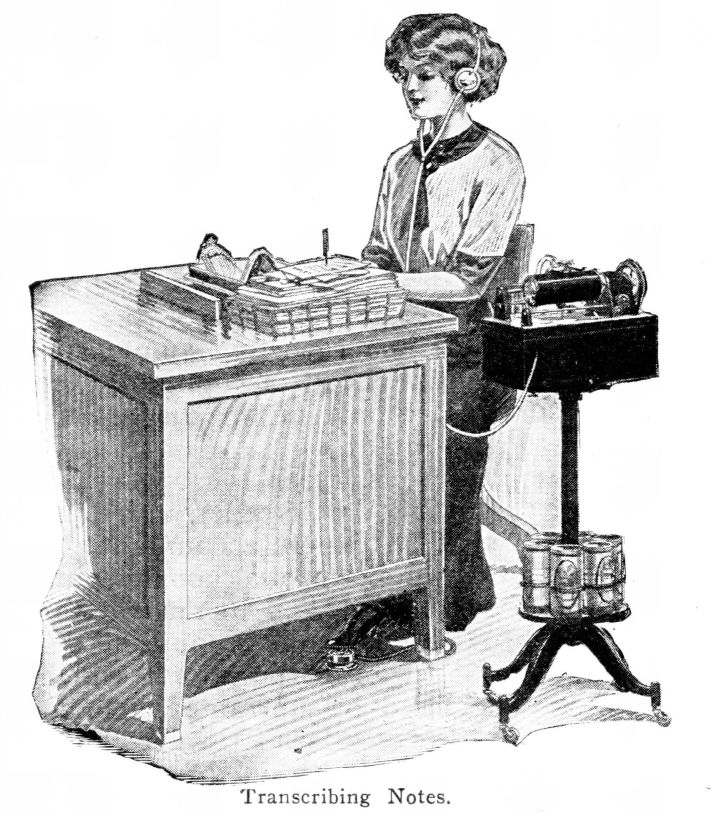

The business phonograph, a machine made expressly for the purpose of handling correspondence, is now used in most large offices to replace the shorthand writer. It records the dictator’s voice on a wax record, which is then taken from the dictating machine and placed on the machine of a transcriber, who proceeds to type the matter recorded on the record. An economical shaving device can be purchased with the phonographs and the records can be shaved and re-used one hundred times, so that the cost of the records really does not amount to more than the cost of supplying notebooks to the shorthand writer.

ONE OF THESE DICTATING MACHINES, COSTING EXACTLY ONE HUNDREDS DOLLARS REPLACES PERPETUALLY IN A MODERN OFFICE, ONE EXPERT, STENOGRAPHER COSTING ONE HUNDRED DOLLARS A MONTH. THERE ARE AT LEAST A DOZEN OTHER MACHINES NOW COMING INTO COMMON USE WHOSE EFFECT IS TO THROW OFFICE WORKERS OFF THE SALARY LIST AND INTO THE STARVATION ARMY.

These machines are causing an entire revolution in the method of handling correspondence and also in scientific office management. The plaint of the business man who had stenographic work to be done was that he was unable to find high grade stenographers. But the modern office manager, the “scientific efficiency expert,” in the application of “scientific office management” to his business, has found how to avoid this difficulty.

Machines the Solution

The shorthand reporters of the courts throughout the country had long since discovered a solution of the problem of inefficient stenographic help which faced the business man. When the reporter was in court for four or five hours taking shorthand notes it was necessary for him to spend three or four times that long to transcribe them himself. Or it was necessary to sit at the side of a typist and dictate to her. Of course, this latter method was inconvenient to the reporter, because he had to waste almost as much time waiting for the typist to “catch up” as it would take him to transcribe the notes. And the strain of taking and reading his own notes made it almost impossible for a busy reporter to transcribe them himself.

In searching for a solution of his problem, he became acquainted with the phonograph or dictating machine. He found that by simply reading his notes into one of these machines, as fast as he could talk, and sending the records as they were finished to typists—who would put them on other phonographs set to reproduce the dictation—he could divide his work up so that two or three typists would be transcribing at the same time he was dictating, and he would thus be able to finish up his work in a very rapid and efficient manner.

So, likewise, the office manager found that the dictating machine would solve his problem. But unlike the court reporter he was not willing to pay a good salary for this character of work. The very nature of the service required by the reporter made it economical and necessary for him to hire the highest grade typists and to pay them on a piece-work basis, because of the fact that speed and absolute accuracy were the first essentials of his profession. He could only get the kind of service he required by making such an arrangement. On the other hand, the office manager found that where it formerly took the services of five fifteen-dollar-a-week men or women, making a total expenditure of seventy-five dollars a week for stenographic help, he could now hire five girls at a salary of eight dollars a week. And by having them use the phonographs, these eight-dollar-a-week girls would turn out as much work as the high grade stenographers had been able to do, and at a saving of thirty-five dollars a week in his expense account.

Half the Stenographers Lose Jobs

Or the office manager could dismiss half of his force of experienced stenographers and the remainder would be able to do as much work as the whole force had formerly done, using the dictating machines. He found that by buying enough of the machines to keep the operators busy at all times, he could thus increase the work produced one hundred per cent. The operator’s whole time was now occupied in transcribing dictation, and transcription from the machines could be carried out at a considerably more rapid rate than from either notes or copy. And in addition to this he found that the phonograph would record dictation at a much faster rate than any stenographer could, and reproduce it with absolute accuracy. It always “got you.” It never missed a tense—it never skipped a syllable. It could not transpose. And in addition to that it was always “on the job” day and night, to take his dictation whenever he desired it, and the records could be turned over to the typist during the day, and thus keep the typist busy from the time she reported at the office in the morning until she went home at night. The office manager can now make a machine of the operator. When the operator reports in the morning, regardless of when the boss arrives, she immediately goes to work and transcribes the “canned” notes until lunch time; after luncheon the work is resumed and the typing is continued until quitting time.

If the typist does not want to become a machine and complains, the manager simply says, “Well, you can quit, I can easily find somebody to fill your shoes.” And so he can. He simply has to call the typewriter company’s office, and the employment department will put him in touch with another typist within a half hour. There are hundreds waiting at all times, and all glad of an opportunity to go to work.

There are now in operation, in Greater New York alone, more than twenty thousands of these business phonographs. The stenographers and typists, realizing the dawn, of a new era, are forced to overcome their dislike to being made machines of, and a great many of the most competent, educated shorthand writers are now forced to do phonographic transcription work, because of their inability to secure positions as shorthand writers which pay a living wage. The regime of the stenographer, excepting, of course, the professional reporter, is surely passing.

But the modern office manager has not alone confined his attention to the stenographer and typist. He has made his inroads into the clerical and bookkeeping forces as well. And here again machinery has been his greatest aid. One addressing machine with an office boy to operate it, will replace the services of a dozen clerks who addressed envelopes by hand. The machines for the reproduction of facsimile typewritten letters have entirely revolutionized the circulation departments of large offices. One of the machines will replace dozens of typists. And office boys can operate them efficiently. The adding and calculating machines have likewise caused similar changes in the accounting departments.

The invention of modern bookkeeping systems has almost eliminated the ordinary old-time bookkeeper. This position in the modern office is now filled by mere clerks. And dealing, as each clerk does, with only a certain portion of the accounting, and then reporting summaries to a confidential head accountant, the firm’s affairs are only at the disposal of this head accountant.

These conditions lessen the opportunities for the trained bookkeeper, unless he can qualify as an expert accountant, by lessening the number of real bookkeeping positions to be filled, and increasing the number of positions in the accounting departments of large corporations which can now be filled by untrained help at considerably lower salaries than it would be necessary to pay to trained men.

The “clerk” does not need be able to figure accurately, or even to write a legible hand. He has machinery to do all of this for him. He simply needs be a machine operator. And the machines are so simple that anyone can operate them. The only essential requirement of the clerk is that he be able to read. He can learn to be as efficient in a few weeks through the use of modern office machinery as if he had put in years of study at mathematics, penmanship and business practice. The head accountant will supply the business practice for him, and the machines will write and calculate for him.

And so, if, on a stormy winter night, you should chance to walk down and scrutinize the faces of the men in the bread line, you will see among the longshoremen and the teamsters, the stenographer and high class accountant, each glad to get his midnight chunk of bread and tin cup of black coffee. And don’t forget! For each man in the bread line there are two girl stenographers out of a job, shivering in some hallway over night, “cleaning up” in some public washroom and hurrying with empty stomachs and aching hearts to the employment agency of the typewriter company or the Y.W.C.A. Vain hope! Her job is gone, and gone forever—while the machines are owned by the capitalist class.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v14n10-apr-1914-ISR-riaz-ocr.pdf