An extremely valuable article for understanding not just the epic garment workers’ strike, but the divisions within the Socialist Party and labor movement . One of the most important strikes of its time, the 1910 Chicago garment workers strike went down to defeat, but began a wave of strikes and organizing in the industry. Robert Dvorak was the lead reporter on the strike for the Chicago Daily Socialist…until he began reporting on the rank and file’s rejection of the union leadership’s offers. Dismissed by his ‘Socialist’ editor, Dvorak gives the behind the scenes workings of the Party, particularly the lamentable conduct of future leading Communist J. Louis Engdahl. That this article was printed in ISR, bête noire of the Daily Socialist, is telling in itself.

‘The Garment Workers’ Strike Lost: Who’s to Blame?’ by Robert Dvorak from The International Socialist Review. Vol. 11 No. 8. March, 1911.

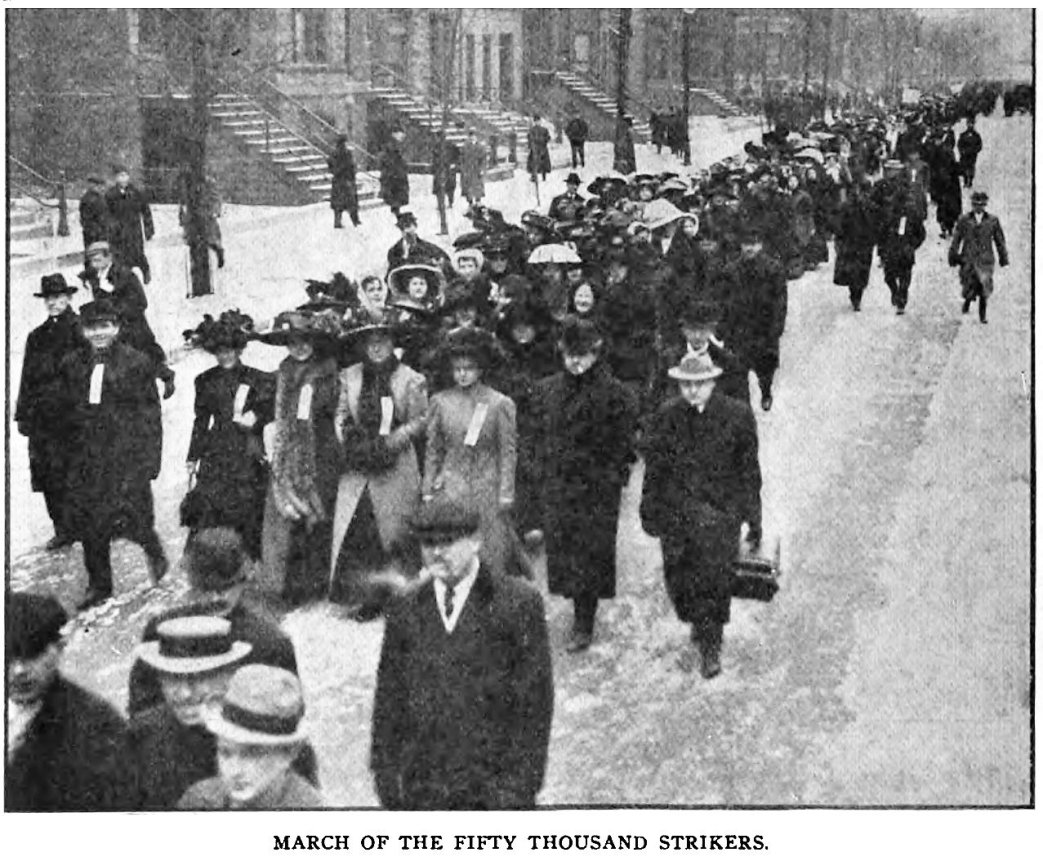

Having written the very first account of the great Garment Worker’s strike in the Chicago Daily Socialist and having worked with the strikers by day and night throughout the sixteen weeks of their marvelous struggle, I will now attempt to depict the many events that led to defeat as briefly as possible.

None who witnessed the wholesale and enthusiastic walkout of the tailors felt for even a moment that it might end disastrously.

The strikers were keyed to the highest pitch of enthusiasm and resistance.

Eighteen of the largest halls in Chicago were packed daily—some even twice daily—and speakers in every language counselled and spurred the thousands to action.

In spite of the first serious misstep of the union leaders, that of making the “closed shop” a battle cry, and later ridiculing it, I felt that the victory of the strikers was inevitable. The “closed shop” error, I thought, would be dropped if satisfactory terms were presented.

When I entered the strike field as a reporter for the Chicago Daily Socialist I had no idea as to what tactics would be pursued by the union leaders. I figured that only such steps as would lead to the earliest and best settlement would be taken from day to day. But imagine my surprise when about the fourth week of the great strike I discovered that no thought whatever had entered the minds of the “far seeing” and “competent” officials to call a general strike of all the tailors in Chicago, in spite of the unanimous demand for such a call.

Without delay I went to Robert Noren, president of the district council of the United Garment Workers of Chicago, who was handling the strike in President Rickert’s absence, and inquired whether or not he intended making an official call for a general strike. He grunted an evasive answer. I grew angry then and told him that I would put a call in the Daily Socialist in the name of the strikers unless he issued an official one. He then told me that one would be made the following day.

The next day I rushed to his office again and he handed me a call signed by him and others of the organizers. Imagine my surprise, however, when on reading the call I discovered that it affected all but the garment workers working in the union shops. I drew Noren’s attention to this and he told me that they could not conscientiously call a strike in the shops where they had signed contracts with the proprietors. This was the second and most serious misstep, for the strikers were already complaining that garments for the strike bound houses were being made in the union shops.

There were about 18,000 garment workers on strike before the call for the general strike. Inside of a week this number was swelled to 45,000. This great exodus was brought on because 50,000 copies of the Daily Socialist containing the call were distributed by the strikers throughout the city and in front of the unfair concerns’ doors.

Enthused by the response to the call, the strikers began to demand that engineers, teamsters, elevator conductors, electricians and janitors, employed in the strike bound shops, be called out. Noren was in favor of this step and I began to voice it in the Daily Socialist in spite of the ridicule of Editor Engdahl.

The cry for a general tie-up of all the garment shops in Chicago was at its highest pitch when the first peace, offer of Hart, Schaffner and Marx, signed by President Rickert, was presented to the strikers and indignantly condemned by them at all the halls.

Then began the attempt to demoralize the strikers and force them to accept the agreement. Benefit money was held back for various reasons and great crowds of indignant men and women gathered in front of the union headquarters at 275 La Salle street. These were each time dispersed by the police, amid the clicks of cameras manipulated by capitalist press representatives.

Up to this time the distribution of strike benefits was left in the hands of Miss Jennie Flint, treasurer of the United Garment Workers’ district council, who in spite of all her natural coolness of head was almost prostrated with fatigue and the excitement reigning at the office each day. She was forced to sit back to back with Noren, the hot-tempered gentleman who shouted and cursed at the little men and women who dared to approach him for information or aid.

It happened on several occasions that Miss Flint was late in coming to the office. The strikers came on the appointed time for their benefits, and the door would be shut in their faces. Noren would curse and roar and capitalist press reporters would be on hand inquiring loudly if the funds had given out or if Miss Flint had absconded with the money. This was done within the hearing of the strikers and pandemonium was the result.

Until the time of the Rickert agreement the Chicago Federation ‘of Labor officials positively refused to take a hand in the strike in spite of the many suggestions made to this effect. There was a personal animosity between the officials and Noren of almost six years’ standing.

Following the excitement brought on by the unfortunate Rickert agreement, a committee of the strikers appealed to the delegates to the Chicago Federation of Labor in meeting assembled and then it was that the Women’s Trade Union League and the Central Labor body took an active part in the struggle.

The Women’s Trade Union League, headed by Mrs. Robins, took upon itself the distribution of aid. Three commissary stores were established, meal tickets good at several restaurants were passed out and coal checks were issued.

This work was carried on in a fairly creditable manner until the slightly remodeled Rickert agreement was brought to life again and presented to the strikers by Mrs. Robins and President Fitzpatrick with an endorsement from the Chicago Federation of Labor and the Mayor Busse aldermanic committee.

Upon receiving a very indignant reception from the strikers, Fitzpatrick and Mrs. Robins grew very indignant and determined to push the agreement over, claiming that only a few hot headed agitators were causing the rejection.

Right here the real end of the strike grew visible. Orders were sent to the various hall chairmen to allow none but those speakers armed with credentials signed by Mrs. Robins or Fitzpatrick the floor, and a statement was issued broadcast that the agreement would not be considered turned down until another vote was taken.

In the Daily Socialist I stated that the cutters’ meeting at Federation hall had accepted the agreement with the proviso that a similar action would be taken by the other striker’s. Then when I witnessed the disfavor with which it was received at the other halls, I wrote that the cutters had turned it down also. In this report I was strengthened by the telephone message sent me by a United Press reporter who stated that it had been turned down by the majority of the cutters at a later meeting.

I did not know that I had committed an unpardonable crime until the next day, when Raymond Robins, who had some interest in the Daily Socialist, called me up and indignantly demanded why I had written that the strikers were not in favor of the agreement. I told him that I had reported only what had actually occurred, and he called me a liar.

Then upon cooling off slightly, he began to argue by telling me that the strikers were in a desperate condition and that the funds of the Federation were not large enough to continue the strike with the present number of dependents, and that I was inhuman in furthering their insane determination to stay on strike. He stated further that the cry for a closed shop was bosh and that the agreement was a good one.

I told Robins that I was not reporting news of the strike to suit the whims or desires of the Chicago Federation of Labor or the Woman’s Trade Union League, but for the workers involved in the strike, and that their decisions were the law which would govern my reports of the strike. Robins then began to bluster about losing the good will and favor as well as the support of organized labor, including that of his wife and himself. I informed him then that this was not my concern, but that of the Board of Directors, but that as far as I was concerned the good will of the 45,000 strikers was of more value to me than that of a hundred Federations of Labor and Robins families.

J.O. Bentall, States Secretary of the Socialist Party and a member of the Board of Directors of the Daily Socialist, was next appealed to by Robins and given the same ultimatum tendered him by me.

The following day I was visited by Miss Pischel, a Socialist woman who had secured work with the Woman’s Trade Union League during the strike. She began to upbraid me for sticking with the stupid strikers, who knew not what was best for them. She was soon followed by a Socialist named Esdorn, who declared that the strikers had not turned down the agreement, and that I had lied deliberately in order to satisfy a personal ambition. Bentall and I took Esdorn to a meeting of strikers in the Young People’s Socialist League hall, and upon hearing the sentiment of the strikers regarding the agreement he said no more and disappeared.

Failing in inducing me to write to suit the taste of the union leaders, the emissaries of the Federation of Labor and the Woman’s Trade Union League took the last step. Miss Pischel, Eleanora Pease and C.M. Madsen, all of them Socialists, closely allied with the Federation through various positions, wrote letters to the Board of Directors demanding my dismissal. They claimed that by my reports I had angered union officials and undone the good work of many comrades who were endeavoring to prove to the organized world that the Daily Socialist was its friend.

As a result of the letters I was called before the board the following Thursday. There the letters were read and I was told to prepare an answer for the next meeting. The unique part of the letters was the fact that they all read alike and began by a statement that the writer had heard I had written certain things. Evidently none of the writers had read the reports in the Daily Socialist. Instead of charging me, as they had when they had visited me, the writers based their attack mainly upon a story I had written in the January issue of the International Socialist Review.

When I appeared before the Board of Directors for the second time I had a complete statement of the work I had done on the strike and a declaration of my principles, in which I stated that as long as I reported the strike I would do it with a view to satisfying the strikers, in compliance with the national platform of the Socialist Party, and would not muzzle things to suit the Chicago Federation of Labor or any of its subordinate organizations, which were rife with internal squabbles, especially when these were condemned by the strikers at every hall meeting.

Prof. Kennedy, a member of the Board of Directors, arose with a motion that I be dismissed, as I was temperamentally unfit to work on the Daily Socialist as a reporter. There was no second to his motion and dissension arose among the Board of Directors. Kennedy then declared he would have to leave the meeting, as he had an appointment elsewhere. He was followed by George Koop and by Axel Gustafson. There was some more haranguing, and then Barney Berlyn arose with a motion that the matter be left for settlement with J.O. Bentall, Carl Strover and Business Manager Stangland. Thomas J. Morgan, the seventh member of the board, was not present.

The three deserted officials of the Daily Socialist argued my case for over an hour, Bentall would not stand for my being dismissed or even taken off the strike, and Strover held that I could not stay as the strike reporter. Finally I was asked to choose some other position on the paper. I was determined to see the strike through for many reasons and refused to accept any other position. As a result I did not report for other work.

Previous to the second board meeting William D. Haywood had arrived in Chicago upon the request of the strikers, who wanted him to speak at the hall meetings. On the Sunday following the first meeting of the board Haywood spoke to over 6,000 strikers in Pilsen Park. Fitzpatrick, Emmet C. Flood and a number of the union organizers were present. The audience would not listen to these until they had heard Haywood and cheered him for almost ten minutes. Fitzpatrick followed Haywood and opposed him on many points.

Haywood’s declaration that a general strike of all the tailors, including those in the union shops and other mechanics working in the strike-bound houses, ought to be called, was greeted with deafening cries of approval.

When I wrote the story for the Daily Socialist on Monday, Editor Engdahl cut out all reference to Haywood’s speech and his future meetings. I objected, and was told that he was running the editorial end of the paper. There was no gainsaying this and I had to be satisfied, but I told him that if it were not for the fact that my case was coming up before the board the following Thursday I would quit right away, as I had no desire to work on a muzzled paper. The next morning I found a new man at my desk.

The third meeting of the board over my case was held earlier than usual, and when I appeared at a quarter to seven o’clock my case had been disposed of. When the fourth meeting took place I asked to see the minutes of the previous session regarding my case and found the following:

“In view of the fact that the strike is practically settled, and the fact that Dvorak has not appeared for work, it is the sense of this board that he has resigned.”

As some of the biggest conflicts of the strike took place since the previous meeting of the board, Thomas J. Morgan, who was not present at the fourth meeting, made a written motion that my case be re-opened. Gustafson pushed the motion, but the board would not agree. Then I asked point blank why it was that the board desired to have me taken off the strike. After some hesitation I was told that I had antagonized the Federation of Labor by what I had written, and that for the well being of the paper it was best that I be removed. I then told the board that if such was the case I had no desire to work for the Daily Socialist, as I never would twist facts to suit the “Labor Body.”

After having had the agreement printed in five different languages the union organizers had the leaflets handed out at the halls preliminary to taking a vote. Four days elapsed before any step was begun towards taking a vote on the agreement, and when the time finally arrived the floors of the halls were strewn with the leaflets bearing the agreement torn into shreds. This show of anger and indignation on the part of the strikers frightened the organizers and no vote was taken. Instead, however, the peace offer was dropped temporarily.

I was not reporting the strike at this time, and no mention of the agreements being torn up was made in the Chicago Daily Socialist, but there were hints of the strikers looking upon the agreement with more favor.

About this time the strikers who were disgusted with the tactics of the union leaders almost a month back decided to take things into their own hands. They called a conference of the Bohemian, Polish, Slovak and Lithuanian strikers. This conference decided, since the union leaders were bent on offering only worthless agreements, that the strikers frame demands of their own and present these to the officials of the various strike-bound houses. The demands framed and accepted by over 18,000 strikers are as follows:

“All former employes to be reinstated in their former places of employment.

“All grievances of employes shall be presented to the representatives of the firms by committees representing the employes of each shop where such grievances may arise. Any adjustment of such grievances must be ratified by the employes of such shops. Parties not interested in the controversies shall not interfere except by mutual consent of the employes and employers.

“Fifty (50) hours shall constitute a weeks work. Nine hours shall constitute a day’s work except Saturday, when work shall be confined to five hours.

“All workers, without exception, shall be granted an increase of 15 per cent in wages as compared to wages paid prior to the strike. Piece work shall be abolished wherever agreed upon between committees provided for in Section 2 of these propositions.

“No employe shall be compelled, under any pretext, whatever, to sign individual agreements waiving any rights to the price established by the wage scale.”

As soon as the Federation of Labor officials got wind of the strikers’ action they molded the last link of the chain of despicable tactics. They decided to end the strike under any circumstances and forthwith, according to strikers who were present, packed Hod Carriers’ hall one Saturday afternoon with 1,500 or more tailors employed in the newly signed label shops. With these recruits, who were getting a half holiday, present in the hall another vote was taken and the strike at Hart, Schaffner & Marx declared off.

Thousands of the angry strikers rushed to their halls on Sunday in order to protest against the action taken, but found these locked. On the doors were cards declaring that the hall was closed by the order of the United Garment Workers’ Union and the Chicago Federation of Labor. Only the halls in which the Bohemian strikers met were open, and these, located on the southwest, side of the city, were crowded to suffocation with protesting strikers.

The reason that these halls, National, Pilsen Park, Sokol Chicago, Krizek’s and Radouse’s, were not closed was because neither the Federation or the United Garment Workers’ organization had paid for them. They were managed, by the Bohemian strikers independent of the union from the very beginning. The Bohemian strikers had received but very few dollars from the Federation because they had conducted their own relief and collection work in their own division. They had received only insults and slurs at the union headquarters, both from Noren and Fitzpatrick, as happened to Alberta Hnetynka, secretary of the Bohemian strikers, and James Balvin, president of the same organization.

Monday morning, following the ending of the strike at Hart, Schaffner & Marx’s, strike pickets who went to the shops were confronted with a more than redoubled cordon of police. The reinforcement had been asked by the union leaders, who wished those of the returning employes to be guarded against the pickets. Only several hundred of the strikers went back to work Monday, and many of these went to the strike headquarters that evening complaining of the sneer directed against them by the scabs, with whom they were forced to work side by side. At the end of ten days, when, according to the agreement tendered by Hart, Schaffner & Marx, all of the old employes were to be accepted, several thousand were still refused work, and it took the personal demand of the union leaders to get many back to work in the various Hart shops.

The firm of Kuppenheimer, when confronted with a committee bearing the demands of the strike conference, declared through Mr. Rose that these were agreeable. Again, upon hearing of the step taken, the union leaders took a radical step and informed the strike conference that if they carried out their intention they would be an outlawed body as far as present organized labor was concerned.

The new threat of the Federation was considered by the strike conference, and it was decided that as the backbone of the strike had been broken when the Hart, Schaffner & Marx strikers returned to work, there was but little use in trying lo rectify the harm done. The strikers were disgusted and were returning to work in large numbers, and before a week had elapsed only 500 of the 6,000 Bohemian strikers showed up at the meeting. All of the strikers realized that they had been duped, and they had no desire to wait for another of the so-called victories. They went back to work, but they had learned the great lesson that everything bearing the name “union” did not mean solidification of the workers’ ranks. They realized that solidarity could not exist in an organization that was split up into unions each scabbing on the other in time of strike in spite of the fact that they performed the same work. They realized that united action could not exist where the great body is chopped up into atoms widely separated and separately governed.

At all of the meetings held daily during the sixteen weeks of the strike the tailors condemned the Chicago Federation of Labor, which allowed union men and women to scab on the rest of their brothers and sisters for twenty-five cents a week, just because an agreement had been signed with the garment boss. They unanimously applauded the Industrial plan of organization as explained by Industrial speakers. They went back to work losers, the majority of them for much less wages than had been received before, but victors because of the great knowledge gained during the strike.

The great garment workers’ strike is at an end. The workers have gone back to the shops, although hundreds of them may never get work in the shops, but the doubts in the minds of the strikers can never be hushed.

Where did the fifty-cent pieces collected from about 35,000 strikers as initiation fees go to?

Was Arkin, the professional bailer, employed in the strike, being paid $3 for every one of the 850 or more strikers arrested? If he was, why was he when most of the bailing could have been taken care of by volunteers, as was the case with Mr. Tyl, who bailed out a large number of Bohemian strikers?

Why were there five or more paid lawyers hired to defend the strikers when a large number of Socialist attorneys volunteered their services free of charge?

How much were these lawyers paid?

Why was it that when Anna Krai and myself were arrested and tried before a jury Attorney Sonsteby and ex-Judge Herely spent over a whole day of their most valuable time in the court room, when Sam Block, a Socialist lawyer, was present and would have taken care of the case, which was dropped after a five-minute hearing given the policeman who arrested us?

Regarding the question of whether or not the strike was sold out I have only this to say: In my first story published in the January issue of the Socialist Review, I depicted the terrific competitive battle raging between the association of tailor bosses and the renegade firm of Hart, Schaffner & Marx. I pointed out in the story that the weakest would soon give in to the strikers as soon as the busy season began. Hart, Schaffner & Marx capitulated the minute it offered the first peace terms. If the screws would have been tightened on Hart, Schaffner & Marx harder than ever at this time by the Socialist press and the union leaders, the firm would have given in on’ terms much more favorable to the strikers.

Instead of tightening the screws, however, Mrs. Robins and her colleagues did everything in their power to discourage the striker and encourage the renegade firm. Mrs. Robins, for instance, gave capitalist press reporters column stories telling of the awful conditions in the ranks of the struggling tailors. She told vivid tales of the acute suffering among the men and women and of the lack of funds in the treasury of the league.

The strikers objected to these stories at every hall meeting, and in one even passed resolutions condemning the news items. When these resolutions were given to me by a committee from Washes’ hall, Mrs. Robins grew very indignant and forbade the publication of the grievance.

Just previous to the tricky acceptance of the last agreement, the Chicago Federation and the Woman’s Trade Union League shut up the commissary stations. This came as a hint of what was to happen if the strikers persisted in refusing the agreement. After the acceptance, the commissary stations remained closed for fear that some of the Hart-Schaffner people might not return to work.

All of the efforts of the strikers after once Hart, Schaffner & Marx offered peace terms were directed towards ending the strike with that concern. The firm was encouraged in every way to hold out and the strikers demoralized and condemned for daring to resist. It looked to me as if Hart, Schaffner & Marx had told the officials that if they helped it to settle the strike before the busy season advanced it would in turn help the strikers defeat the association. That I was not mistaken in this theory was proved when after the Hart, Schaffner & Marx people returned to work the organizers told the strikers to stick because even the efforts of Hart, Schaffner & Marx would be directed against the brutal Association. This was the policy that defeated the strikers.

The business men who gave from 10 to 25 per cent of their daily profits deserve great credit. The Women’s Socialist Agitation League, the members of which worked like Trojans on the special strike edition, under the direction of Mrs. Nellie G. Zeh, deserve honorable mention, as do the citizens who took the children of the strikers into their own homes in order to relieve the hardships of the heroic fighters. Then there are the grocers, butchers, shoemakers, bakers, druggists and milkmen who gave freely of their stock; the physicians, dentists, actors, musicians, barbers and occulists who donated their services throughout the strike; the landlord and hall owners who gave their property free during the struggle, and the proprietors of theaters and nickelodeons who gave benefit performances.

Of the unions affiliated with the Federation the greatest credit falls to the United Mine Workers in Illinois, who, in spite of the fact that they had just ended a serious fight of their own donated great sums to the garment strikers. The Bakers, Brewers and Ladies’ Tailors also gave considerable sums, as did the Arbeiter Kranken and Sterbe Kasse.

As I said before, the strike was lost as far as material gains are concerned, but it was an education which in the end, after all, is even better than a gain of a few cents. The strikers have come nearer to gaining a closed shop in reality than if they had it guaranteed on paper. They have learned that a closed shop exists as soon as the workers learn the lesson of solidarity and unity of action.

The one great proof that the strikers have learned this lesson lies in the fact that meetings independent of the Federation or the Garment Workers’ Union have been held twice weekly since the ending of the strike, and speakers urge the tailors to study class solidarity. The meetings have been well attended, the halls being just as full as at any time of the strike. The tailors are studying and when another strike does come another story will be written.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v11n09-mar-1911-ISR-gog-Corn-OCR.pdf