A thorough report on the the conditions in Denmark and its revolutionary movement from Marie Nielsen shortly after her release from prison. A central figure in the Danish left and early Communist Party, Nielsen was a delegate to the Second Comintern Congress as one of the two Danish Third Internationalist, one a Syndicalist, one a left Social Democrat, groups. Expelled for ‘Trotskyism’ in the late 1920s, she was readmitted in 1932, to quit in 1936 after denouncing the new Soviet ban on abortion.

‘The Situation in Denmark in 1920’ by Marie Nielsen from Communist International. Vol. 1 No. 11-12. June-July, 1920.

During the world war Denmark was in a favourable condition in comparison with the warring countries, as the latter were purchasing at high prices all that was being produced by her. At the Bourse speculation was running riot, day by day fortunes of millions of krowns were being made and numbers of bogus companies started.

The commercial situation was most favourable. In contrast to the time preceding the year 1914 Denmark had acquire considerable assets abroad.

But from a wider social point of view the nation’s prosperity had diminished. Only quite a small clique of industrials and merchants had obtained profits under the existing circumstances and only the larger fortunes had greatly increased, whereas during the whole 5 years the workmen were under the yoke of high prices and a great lack of employment (from 60.000 to 70.000 men in winter time and 20.000 in summer, to the 3.000.000 population of the country); the clerks and employees had become paupers, their salaries haying remained the same in spite of the rising prices.

The Government tried in vain to diminish the contrast between the rich class living in luxury and the impoverished population, by means of the system so well known in all countries of half-hearted governmental “socialism,” which goes no farther than a control over the import and export, the rationing of the foodstuffs, Government subsidies for lowering the prices, relief for the poorer people under various forms, etc.

But these measures had very little bearing on the situation, and even the rationing of the food was felt to be but a class measure, because the rich people were always able to buy anything in the quantities that they wanted.

After the conclusion of peace a change occurred. The whole economic life of Denmark is completely dependent on other countries, as Denmark has neither the raw material nor the sources of energy that she needs, and even the rural industry which is her principal nerve, depends on the import of machinery and forage. The rural industry of Denmark produces almost exclusively ham, eggs, butter, meat, etc.

During the period of war the number of cattle diminished ten times, partly owing to speculation, partly to absence of forage; all the storehouses were emptied, and the population was hungry.

Therefore, as soon as the international trade was resumed, the change in the trade balance was unfavourable to Denmark. During a short period of time we not only spent all our reserves, but the import exceeded the export to such a degree that at present we are owing other countries 2 milliard crowns for goods, and the value of the Danish crown, in comparison with the currency of other countries, has fallen rapidly.

The national debt has grown double during the last 5 years, all the communities have had to contract large loans. These loans are all invested in the Danish banks, and in consequence the latter, besides receiving a good and sure income, have acquired an influence over the political life of the country. (Thus, in 1916 the banks compelled the Government to introduce a whole series of indirect taxes).

A considerable concentration of capital took place during the war, and a number of trusts was formed, both in the banking and industrial branches of business.

The year 1920 brought together with a change of the trade situation a series of bankruptcies of the bogus companies of war time; some of the older firms and a few of the smaller banks broke up also; evidently we are on the verge of a great economic crisis.

The productivity of the country during this period has been declining.

Situation of the workmen.

The Danish workmen are organised into industrial unions, and the latter in their turn have formed into a “Collaboration of Industrial Unions” (De Sammvirkende Fagforbund, D.S.F.). Set against them is a strong Union of Employers.

The liberty of action of the separate unions is bound by the agreement of 1899 (September agreement). The direction in the industrial unions belongs to the moderate opportunists. Negotiations have the preference over strikes, and subsidies over an increase of pay.

The opposition, which has a syndicalist character, has formed its own special clubs in most of the unions; these clubs are united in the “Union of the opposition of the industrial movement” (Fagoppositionens Sammenslutning, F.S.), which publishes a small daily paper of its own Solidaritet.” (Solidarity).

In consequence of internal frictions in the D.S.F. part of the industrial unions became divided and formed the “Federation of Free Industrial Unions” (De Freie Fagforeningers Sammenslutning), in which each union is allowed full freedom of action. The most important among them are the unions of the construction workmen, the seamens’ organisations, and the union of the workmen of the port of Copenhagen.

Some of these organisations have a syndicalist character, others not.

During the course of the war the relative rates of wages became lower, because the increased rates did not correspond with the high prices.

In accordance with official statistics, the pay of an average workman in 1914 amounted to 1350 crowns, in 1918 to 2004 crowns; the purchasing capacity of the crown (according to official statistics), in 1918 amounted to 56 dre, so that the real income was only 1120 crowns, which entailed a deficit of 230 crowns; in the years between 1914 and 1918 the deficit was 50. 110 and 150 crowns.

In 1919 the conditions improved and the deficit in comparison with 1914 amounted only to 185 crowns.

By January 1st 1912 the deficit amounted to 455 crowns, and a statistician calculated that without an essential change in the conditions about 3 years will be necessary for the workman to be able to cover it. That means only, that no effectual improvement has been made in the workmen’s position, except the diminution of the working hours.

The workmen had obtained the increase of pay and the improved labour conditions by their own direct action, by means of agreements and their professional unions, in some cases by hard struggles and “illegal” strikes.

In 1918 the construction workmen obtained the introduction of the 8 hour day by the help of a strike which lasted three months. Later on this improvement was confirmed by legislative order.

On the 1st of February 1920 the terms of 114 agreements expired and the Employer’s Trust declared forthwith that it would not agree to any concessions and at the same time it handed in 25 million crowns to its current account at the banks for “military” expenses.

The D.S.F. was nevertheless compelled to demand concessions for its members in the sense of increase of pay and the improvement of the labour conditions.

Many unions were working at incredibly low rates. The situation of the rope-makers, weavers, paper manufacturers, bakers and some other trades, was especially bad.

However, the D.S.F. informed its members that it had not sufficient funds to continue the struggle.

The negotiations went on for 2 months and led to nothing; at the end of March the employers threatened to have recourse to a general lock out (with the exception of a few branches of production).

The situation suddenly grew more acute owing to political reasons.

During the war the Cabinet was under the direction of the radical bourgeois Zale, who was supported by the Social Democrat party whose representative during the last years in the Cabinet was Stauning.

The cabinet possessed the majority (by 2 votes) in the Folketing (1st Chamber), whereas in the Lendsting (2nd Chamber) the majority was held by the conservative opposition.

In regard to the question of re-elections the Folketing showed an equality of votes, and the King took advantage of the situation to dissolve Zaler’s Cabinet and form a Conservative Ministry.

In reply to this royal coup d’état the Social-Democrat party demanded that the D.S.F. organise a general strike.

The general strike was hailed with enthusiasm by all the labour organisations; it was joined by the railway service and post office employees. All political dissensions were cast aside. The syndicalist organisations joined the strike as well, but they proffered special economical demands, and also a demand for the amnesty of political prisoners. (Many revolutionary and antimilitarist workers were in custody). This demand was included in the programme of the general strike.

The bourgeoisie retired before the unbending will of the workmen. The King dissolved the Conservative Cabinet and formed a business Ministry with 2 Social Democrat members. The political amnesty was accorded. The idea of a general lock-out was given up and it was notified that special negotiations would be held with each industrial union and that the possibility of concessions being made on the part of the employers was not excluded. The “Free Unions” participating in the strike, did not however sign any agreement, as their economical demands had not been satisfied.

They passed an agreement between themselves, and as the seamen and transport workmen in the pert of Copenhagen considered the moment to be a favourable one for a struggle for their interests (a contract had just been signed with England for a large delivery of agricultural products) they did not end the strike but proffered their demands to the larger shipping companies, which had been earning enormous dividends during the war. The other industrial unions decided to resume work, as their refusal to discontinue the strike would have no effect on its course, and to support the strikers economically. Th’s strike is still continuing at present (28.V) for the 8th week. Trade has become completely paralysed, the agricultural products are lying immovable in the storehouses. The strike has caused a fall in the prices for food stuffs.

On the part of the capital the struggle is being carried on with great exasperation. The entire bourgeois press is mobilised against the strikers; attempts have been made to provoke them to various demonstrations; but up to now the workmen have exercised great discretion in respect to provocation. There was an attempt to imprison the leaders, and the bourgeois corps of strike breakers, the “public assistance” (Samfundshjalpen) worked in the port under the protection of the police; the first time it was called to action by the social-democrat Jegen, a member of the Government.

At the time that this stubborn struggle was going on some of the industrial unions had entered into negotiations with the employers. However, the concessions made to the workmen are so insignificant that they cannot lead to a “social peace”; the first “illegal” strikes have already been declared in the shoe industry, after the agreement was signed. But the majority of the industrial unions have not signed any agreement.

Revolutionary movements.

The Danish Social-Democrat policy is following precisely on the lines of the German Scheidemannists. The result of this has been the formation of a new revolutionary organisation in the spring of 1918, the Socialist Labour Party (Socialistiske Arbeiderparti), which is working against the old party. This organisation suffered from the very beginning from a lack of leading forces, because only an insignificant part of the party opposition had entered it, the majority, the leaders of the Social-Democrat Union of Youth, remaining in the party out of tactical considerations with the object of waiting to see what would be its position after the war.

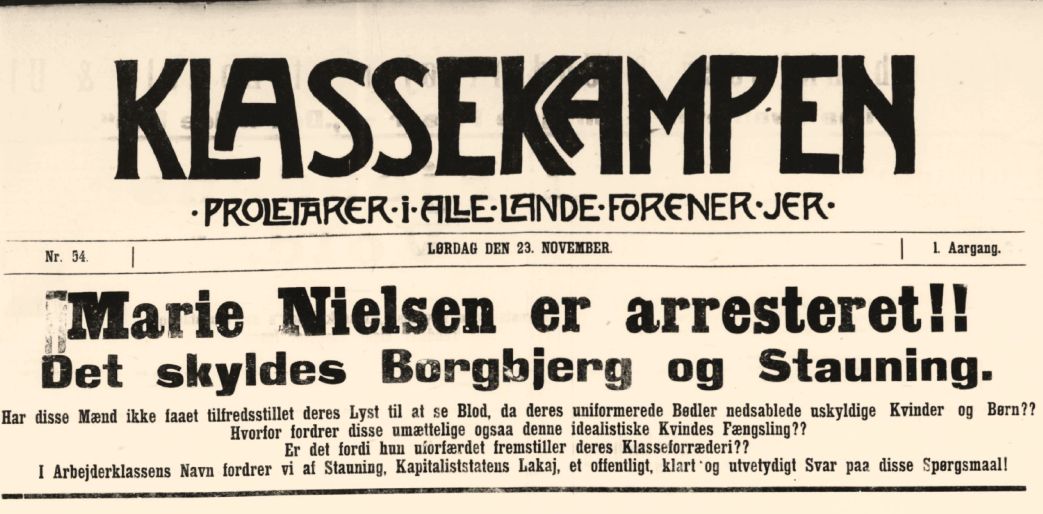

The Socialist Labour Party meanwhile started a strong revolutionary campaign, and in the summer of 1918 conducted several large labour demonstrations (against the high prices and against militarism). The party was soon increased by a number of new members and in October it proceeded to the publication of a small daily paper “Klassenkampen” (Class struggle).

In November 1918 the party together with the “United opposition of the industrial movements” (F.S.) carried out two more large demonstrations in favour of the amnesty of the political prisoners. Matters came to a collision with the police (undoubtedly the work of provocation). The leaders of the party, chairman Tegersen and the editor of the paper “Klassenkampen” Maria Nielsen, were arrested together with a number of syndicalists and put in prison.

After a senselessly long period of detention during 6 ½ months, to which the prisoners put an end by a hunger strike, the leaders of the movement were sentenced to 18 months of severe imprisonment and the rest to shorter terms.

The Socialist Labour Party soon fell into a decline owing to its youth and unstable organisation, and the publication of its paper was stopped.

In the Summer of 1919 the Social-Demokrat Union of Youth decided to break with Social Democracy and they formed a new organisation conjointly with the so-called independent Social-Democrats and members of the Socialist Labour Party, the “Left-socialist party” (Venstersocialistiske Parti), with a small weekly paper “Arbeidet” (Labour).

This party was very weak from the beginning owing to the absence of leaders The latter were to have been given by the Social-Democrat Union of Youth, but it did not take advantage of the favourable revolutionary situation of 1918. By that time the moderate elements gained a considerable supremacy in the Union of Youth; it became divided and its revolutionary part is weak at present.

The party has a parliamentary character to a considerable degree, and distinguished itself by its campaign during the last elections, and a little by its paper, which has but a limited circulation.

The political situation is unfavourable for such a party.

The elections carried out in April 1920 gave the conservative parties a majority both in the Folketing, and in the Lendsting, so that Government power has passed to them.

Social Democracy had regained in a considerable measure the sympathies of the workmen during the general strike and was now forced to pass into opposition. It has broken with the bourgeois alliance and for the forthcoming elections in July it is producing a very radical programme republic one-chamber system, universal suffrage beginning from 21 years of age, “industrial soviets”!

It is undoubtedly incapable of carrying out any truly socialist policy, it is too much infected by the bourgeois frame of mind, but during a certain period of time it will be able to maintain its influence over the parliamentarily inclined working masses, thanks to its “state of opposition.”

At the same. time the class contrasts are becoming more acute; this may be seen from the ever-continuing strikes during which the Social-Democracy is mostly collaborating with the bourgeoisie, helping the latter to disorganise the strikes. Thus, it proclaimed the strike begun by the Copenhagen Bureau of Industrial Unions, to be ended. However it is going too far in this policy and concurring thus in the development of an anti-parliamentary feeling among the workmen.

The so-called “Free Unions” are not only carrying on their strike policy on purely economical grounds, but they are energetically striving to obtain the so-called “right of participation” and the control over the production. In connection with this movement the “Opposition of the industrial movements” is acquiring a leading role and its organ “Solidaritet” is circulated in a considerable number of copies (10,000).

In 1919 “The Opposition of the industrial movements” enlarged its organisation and at the re-elections took up a position in favour of the system of soviets.

However out of fear of the “party” and the parliamentary policy it did not find it possible to join the International.

Almost the same position is occupied by the Socialist Union of Youth, of anarchist tendencies, with a monthly paper of its own “The Red War” (Den réda Krig).

Quite recently in its Congress this Union pronounced itself in favour of the Soviet idea, but it refused to join the Third International, in order “not to be bound by certain methods and tactics.”

In total the organised revolutionary movement in Denmark is still very weak, whereas at the same time the fermentation among the workmen is very strong.

A union between the Left Socialist party and the “Opposition of the industrial movement” (F.S.) and a paper to be published by both together would be very useful.

In this way the revolutionary elements amidst the workmen would be united under a general direction.

However at present a struggle is to be foreseen between these two groups (although up to now they have remained indifferent towards each other); the Left Socialist party has begun to organise its own clubs of industrial opposition; it will meet with the resistance of the “Opposition of the industrial movement” (F.S.)

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/old_series/v01-n11-n12-1920-CI-grn-goog-r3.pdf