Mary E. Marcy and her co-reporter look at the myriad impacts of invention on cotton growing and milling, particularly in the South.

‘Machines That Have Made History’ by Mary E. Marcy and M.G.R. from International Socialist Review. Vol. 15 No. 9. March, 1915.

Just about one hundred and forty years ago, the English farmers who were unable to raise their rents by the products from their farms, earned the balance by spinning and weaving cotton cloth at home. A little later farming became for them a by-product and their principal earnings came from spinning and weaving.

One of the first lines of specialization among laborers was the severing of these connections and the gathering of the weavers in the hamlets and towns of England, when, in order to prosper in the making of finer fabrics, weavers were forced to perfect themselves by close application. Some were journeymen in small domestic shops while others worked by the piece. This latter class was swept away as the industry grew.

Hand-loom factories were on the increase and the product of their labor grew so greatly in demand that a spirit of revolt began to make itself manifest among the workers, when John Watt’s steam engine became commercially practicable and revolutionized the whole industry by forcing the would-be-successful manufacturer to run his machines by steam instead of by human power.

The “mule” and spinning jenny, which had been steadily improved since their invention were now run largely by steam power. Then came the fly-shuttle, greatly increasing the output of the single weaver.

But power looms won their way very gradually, fought every inch of their progress by the hand-loom weavers, who hated factory life, and by the manufacturers of small capital, who could not afford to install steam power plants. But the ease with which the art of weaving could be acquired by the new process helps to explain the wretched straits into which the hand-loom weavers were driven in their battle against the new machine.

But month by month one by one went down to defeat—small employer and skilled weaver—just as all manufacturers and all skilled workers must eventually succumb before the superior machine, the superior motive power and larger capital. The application of steam power to the new machines so lowered the cost of cotton cloth that Lancashire, England, became the cotton factory of the world.

How the Cotton Gin Formed the “South.”

Arkwright’s spinning-machine gave England a monopoly on the manufacture of cotton cloth, because England kept the design of this machine a profound secret from America. It was only a few years after the Declaration of Independence that the Assistant Secretary of the United States Treasury caused to be secretly circulated in England, the following paragraph: “A reward of $500 in gold will be paid to any one who will make and smuggle out of England an accurate model of Richard Arkwright’s cotton spinning machine. Every protection guaranteed and the strictest secrecy assured.”

Arkwright, who was an English barber, had invented the machine that did away with the laborious spinning of cotton by hand. For years it had been his chief pleasure in life to experiment with different sorts of machines and to attempt the making of new ones. His wife complained bitterly that he was always neglecting his real duties in life and playing with foolish machinery when “he ought to be shaving customers.*’ She finally became so disgusted with his “shiftlessness” that she left him. Her relatives approved this step and utterly disavowed all connection with the “lazy, dreamer” Arkwright.

But this is life. The people who follow undeviatingly in the paths laid out for them by their predecessors never are heard of. They are so deeply immersed in the ruts worn deep by their ancestors that they cannot see outside. All they have ever accomplished is to wear the rut still deeper. It is only the people who avoid the beaten path of established habits and customs who have ever done anything at all for society. Later, Arkwright was made Sir John, and must have greatly shaken the faith of his ex-relatives-in-law in their prophetic powers.

England jealousy guarded the secret of the Arkwright machine and passed rigorous laws prohibiting the taking of the machine or models thereof out of the country. In spite of England’s refusal to sell, the young United States were determined to have that spinning machine.

There was as yet no cotton industry in America. Cotton was not even a portion of the Southern farm crop. The very little that was raised was spun by hand by the women, but there were no cotton mills.

In response to the United States’ offer for $500 for a model, an English machinist made brass models of the Arkwright machine to be shipped to America. But he was discovered and his models confiscated. Later a young man in one of the Arkwright mills heard of the American offer and embarked for the United States after some months with only his head filled with plans of the machine he hoped to duplicate in the new land. He soon went to work for a firm which was trying to pattern after the Arkwright method. Here he worked a year before perfecting the new spinning machines.

At this time the cotton that was woven into cloth in America was imported from the East Indies. Cotton raised in America was of low commercial value owing to the difficulty of separating the staple from the seed. This operation was performed laboriously by hand. The foreign cotton, with its looser seed, did not thrive in American soil.

Here then was a great need for cotton cloth and yarn, machines at hand for spinning and weaving it into cloth, but no practicable home cotton supply, because it was cheaper to purchase raw cotton abroad than to pick the seeds from’ the cotton raised at home.

The Cotton Gin.

It was about this time that Eli Whitney, a young Massachusetts nailmaker, turned his attention to the study of law. A prospective job teaching, having failed him in the South, he spent some months visiting a friend who was then experimenting with a small cotton crop. Whitney was amazed to learn that it took a whole day to separate one pound of cotton from the seed.

“I believe I can make a machine that can remove those seeds,” he said. The eagerness with which this possibility was greeted encouraged Whitney to set to work upon his cotton gin. In 1793, his first practical machine was perfected. Though very crude, it performed the difficult work of separation.

This invention gave the much-needed stimulus to cotton growing in America.

England refused to purchase any cotton that had been ginned by the Whitney machine, and, altogether, the inventor received very small reward for his work on the machine that revolutionized American agriculture.

Capitalists took up the invention and made vast fortunes from it and Samuel Slater, who had duplicated the English spinning jenny, became one of America’s pioneer cotton manufacturing millionaires.

The cotton gin multiplied the productive power of the workers from ten to an hundred fold and enabled the cotton planters to increase their product from 18,000,000 to 93,000,000 pounds without any decrease in price during the years 1801 to 1810.

Following the age of machinery in the cotton industry came transportation by water and on land. By 1835 the railroads had penetrated the south and the southern states of America found themselves producing most of the world’s supply of cotton by chattel slave labor. Today they have practically a monopoly of the supply of raw cotton. Our annual crop would outweigh 50,000 persons. By-products.

Dr. Benjamin Waring, grist mill owner, first extracted oil from cotton seed, but not for commercial purposes. Forty years later a small capitalist began to successfully produce cotton seed oil. Other small oil mills sprung up and, in 1890, one of the big American packers visited one of these mills, tasted the oil and sent samples to his northern chemists. Then came a new epoch in food production.

The French government found that cotton seed oil made the base for a fine substitute for butter in the army. This was the origin of butterine. The planters found themselves with a valuable cotton by-product that had formerly been a white elephant on their hands.

Cotton seed oil is really a nourishing and wholesome food product. It is the basis for “hogless lard,” salad oil and one of the best grades, bleached, appears in nearly all the “ice cream” purchased from confectioners—in lieu of milk and cream.

$25,000,000 worth of cotton seed oil goes into substitute lard products annually; 20,000,000 gallons are consumed yearly for culinary purposes, salads, etc. Of the mass of seed shells, after the extraction of the oil has taken place, $4,000,000 worth of hulls are used in making trunks, sample cases, washers, valves and gear wheels. The hull bran makes paper and fertilizer.

The cotton seed kernels are crushed and pressed and the remaining mass is ground into meal for stock feed. Over $40,000,000 worth is now used in stock raising every year.

When we remember the development of chattel slavery in the south attendant upon the raising of cotton, when we recall the titanic battle that ensued between the capitalists employing wage labor and the chattel slave owners, we begin to understand what a tremendous factor machine invention has been in the history of the United States.

The Cotton Mill Workers.

In a recent article on the Southern Cotton Mills (printed in solidarity), by M.G.R., she says:

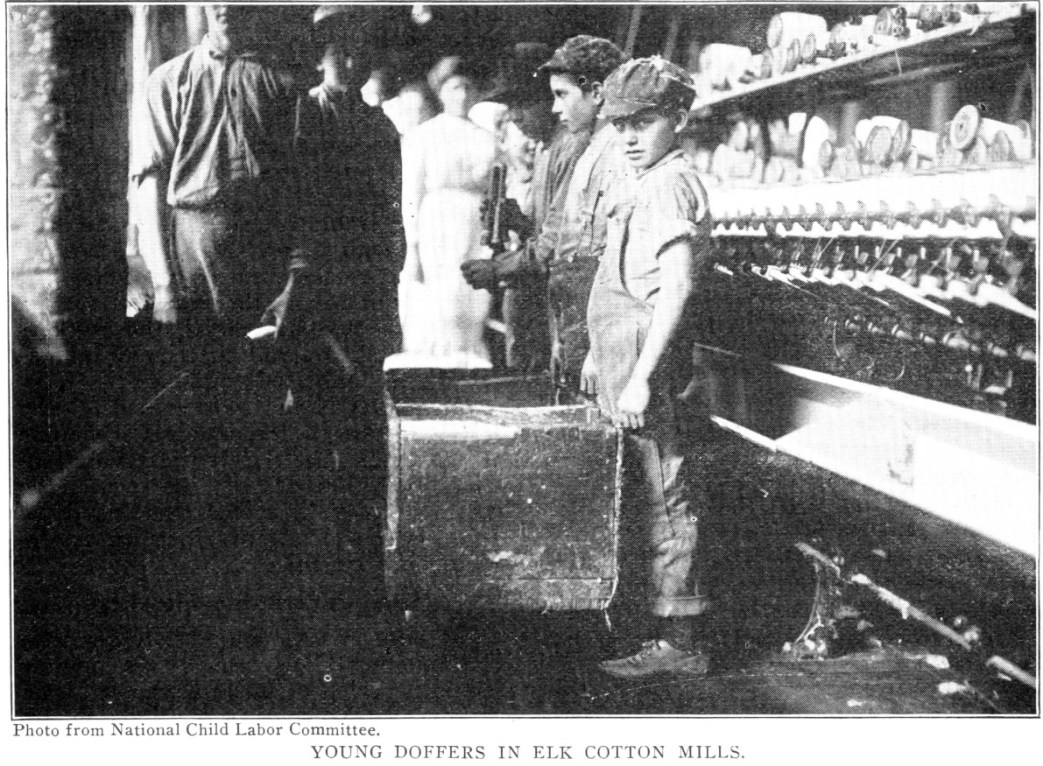

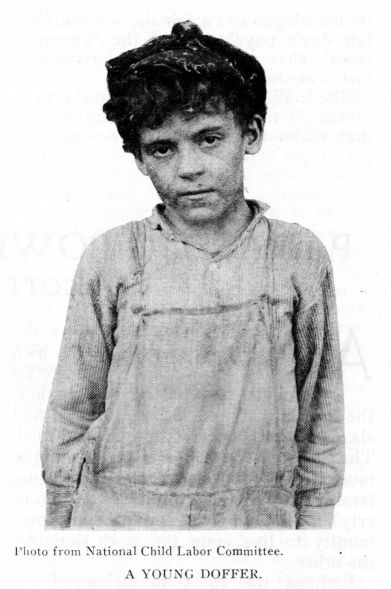

“The cotton mill industry has revolutionized the south. It has taken a new place, and a big place in the American industries. There are now 800 cotton mills in the southern cotton belt where a quarter of a million workers produce an annual output valued at $268,000,000. Modern mills containing the most modern machinery are used and the owners get the greatest results for the lowest possible pay. The southern mill workers receive annually $27,000,000 in wages and produce nearly ten times this amount in value. Northern mills producing $270,000,000 worth of cloth a year, pay $65,000,000 in wages, more than double the wage paid in the South.

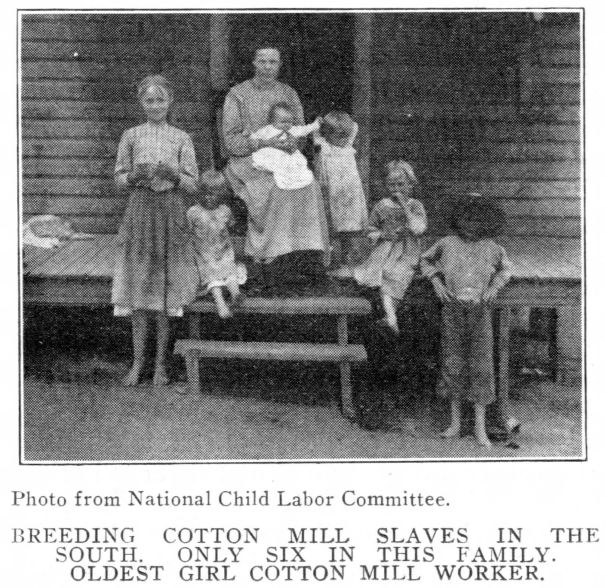

In the South labor is cheap everywhere. It is the cheapest commodity on the market; a commodity that can be obtained at any time, any place to be used until worthless to the buyer and then discarded for a fresh supply. The life of the worker counts for nought.

Nowhere in this country is the life and labor of the workers so cheap and so degrading as in a southern cotton mill. The textile mill worker of the North has, through his many struggles, won for himself some concessions and has, in a measure destroyed some of the feudalism which can be seen in the South in all its hideousness. The northern worker has wrested for himself the right to live where he can; to buy from whichever store his meagre wage will permit; to send his children to a public school.

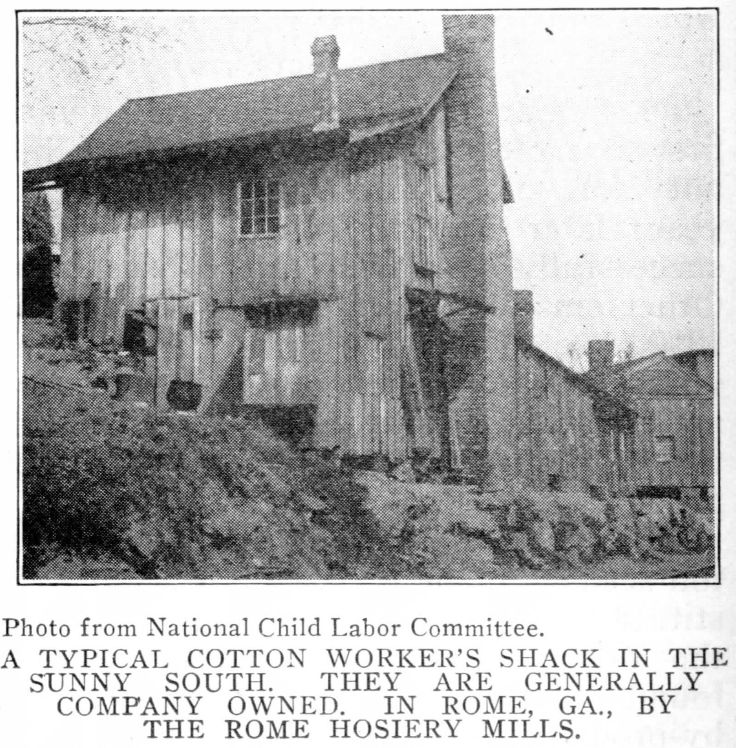

The worker in the southern cotton mill is as true a vassal as ever labored under a feudal lord. He lives in the company house, buys his fuel from the company and usually trades at the company “graball” or store. When not snatched up by the mills, his children attend company schools, instructed by teachers paid by the company. The church itself belongs to the company and the salary of the preacher is usually supplemented by the company. The labor offender is arrested by a company paid constable and tried by a company official, who is a magistrate. And this—in “free” America.

The southern mill worker is a foreigner to the townspeople. They don’t know him and have no desire to know him. When he comes to town it is usually to buy something—on credit—or to attend a moving picture show. More often he just drifts about the streets of the town on Saturday night, wan, ragged, unrelated, a monstrous abortion of industrial tyranny.

The mill worker of the south shifts from mill to mill and from village to village with great frequency. Having little difficulty in obtaining a job, the work being practically the same in all mills, he leaves one mill, vacates a company house and goes to another. The scanty furniture and the children are packed on a dray and he moves. Often I have been to a mill workers’ “home” one week, and coming back the next, found a new family occupying the house and no trace of the old tenant. He changes house, school, store—everything along with the new job.

The same conditions obtain throughout the entire cotton industry in the South. A type of worker has been produced far more proletarian than our brothers of the North. Skill-less, propertyless, unorganized—the South has a real proletariat without the dignity and class consciousness of rebel against his terrible lot.

Organization.

It is out of this material that the industrial union of the South must be built. The greatest obstacle is the apathy of the workers themselves. To teach these workers the first principle of direct action is a Herculean task. We must have a patient, unending campaign—the work of pioneers in this industrial wilderness. It may be possible, by a great deal of agitation, to arouse the textile workers of the South, but unless a permanent organization is effected and a continuous educational propaganda carried on for industrial unionism, the results cannot be far-reaching. To effectively combat the master class an organization must be drilled and trained constantly in the use of its weapons in industrial warfare.

The conditions in the textile industry preclude any form of organization, but industrial unionism. The principal reason, no doubt, why the A.F. of L. has made no attempt to organize the textile workers is that craft organization is not, and never was, possible in the cotton industry. A quarter of a million workers, entirely unskilled, unable to pay big initiation fees or dues, nor to be aroused by the slogan or “a fair day’s work for a fair day’s pay,” are not the “cream of labor” that appeals to the aristocratic tastes of the A.F. of L.

The I.W.W. will have to do the work in the South. And it is a big job; of that make no mistake. The work has been started, some ground turned and some seed scattered. But the big work is ahead of it. To succeed it must be brave, patient and determined to carry the message of revolutionary industrial unionism into the hearts and heads of the cotton mill workers.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v15n09-mar-1915-ISR-riaz-ocr.pdf