Reflections on their execution from Michael Gold, William L. Patterson, James Rorty. Grace Lumpkin, Arturo Giovannitti, Clarina Michelson, James Lilly, and William Gropper.

‘Sacco and Vanzetti, A Symposium’ from the New Masses. Vol. 3 No. 6. October, 1927.

Thirteen Thoughts by Michael Gold.

1. There is no white virgin daughter of Platonic perfection living in this bad world and named: “justice.” There is a bloody battle between classes, and one side wins or the other, and the victory is Class Justice. In Soviet Russia the workers imprison businessmen and their military allies. In America rebel workingmen are burned in an electric chair. This must go on until there are no more classes.

2. This Governor Fuller is a sadist. Revolutionists are not sadists. When their enemy is powerless, as in Soviet Russia today, they grant him wholesale pardons.

3. This murder was committed with all the etiquette and fine, delicate restrained manners of the old Boston families. A sensitive person, I think, would rather be killed by a cursing maniac longshoreman running amuck with an axe. Good manners have become the enemy of freedom in America. They are the last refuge of our scoundrels.

4. Mr. Villard of the Nation owes the world an apology. Because he had dined with Governor Fuller, and found him a man of polite speech and correct table manners, he issued a page of fulsome praise of the murderer on the very day this sadist announced his decision to go through with the killing. Mr. Villard also deprecated violence so often that Nation readers must have gotten the notion Sacco and Vanzetti were men of violence. Also Mr. Villard seemed to believe the subway bombs and the bomb at the juror’s home were placed by anarchists. If I were going to be hung, I should not want such friends to stand by me. They are too weak and faithless.

5. Others to be blamed were Walter Lippmann and his fellow editors of the New Republic. It was they who once proudly announced that they had “willed the war.” This case was one of the many gallows-flowers of the beautiful liberal Wilsonian war they had willed. I hope it will be tigers or monkeys or madmen who are to “will” the next war.

6. The highly-paid respectable lawyers for the defense tried for many years to confine this case only to the law courts. They were indignant when workers all over the world roared in savage voices that Sacco and Vanzetti must not die. One must not trust lawyers in labor cases too much. They are as infatuated with their jobs as are policemen or society women. Fred Moore, the first lawyer in this case, was the only one who appealed to the workers of the world to save the two Italians.

7. Every recent immigrant in America now is certain that the immigrants who stole America from the Indians are a weak, dying, bloodthirsty, superstitious pack of assassins.

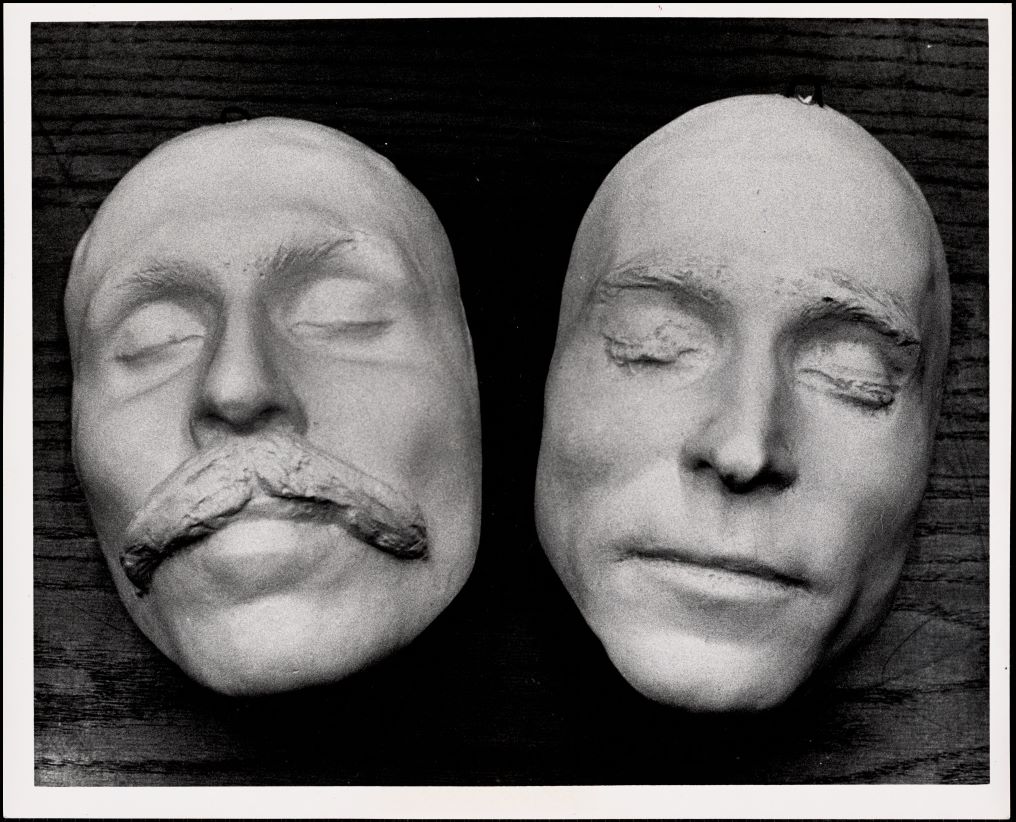

8. The death masks of Sacco and Vanzetti were on exhibition for three days at an East Side hall in New York. About one hundred thousand men, women and children passed the guard of honor, workers in red shirts. They saw the serene face, the long, gaunt face of Vanzetti, the peaceful face of the poet of revolution, who sees through the storms and reads the Red future of humanity. They saw the bold, proud, gallant sneer on Sacco’s face. He looked at judges, wardens, ministers, newspapermen and politicians in black coats around him at the electric chair, and called them: “Gentlemen!” and called them “Merde!”

9. When the bodies were taken from the chair they were bursting with blood at various points, as if President Lowell had been jabbing them with a knife, over and over again, with loud cries.

10. To become a legend for millions of fishermen, coolies, peasants, miners, steel workers, housemothers, Red soldiers, pick-and-shovelmen, war cripples, hounded girl prostitutes, prisoners, Negro slaves, poets, Einstein, Barbusse, ablebodied seamen and Jewish tailors: to Be their battlecry, their red flag:

That is a beautiful fate, it cheats the grave of darkness, it makes sweet even those last leaping fiery minutes in the electric chair!

11. Most of the world now hates America. When the war comes in which Europe and Asia unite to down the new bloody Empire, the cry of “Sacco and Vanzetti!” will be on their lips.

12. Millions of American school children will remember the names of Sacco and Vanzetti, and will study their lives through curiosity when they grow up. Governor Fuller has sped the revolution in this country by ten years.

13. How Sacco and Vanzetti grew during their martyrdom! What great men live in the obscure depths of the ocean of the workers’ revolution!

Farewell, Sacco and Vanzetti!

Hail, the World Revolution!

A Negro in Boston William L. Patterson.

For generations Boston Common has remained inviolate, the place where the voice of the people might be heard. But I soon discovered that the traditional right of the people did not include the right of criticism of a government bent on murder. I became one of a small group armed with placards bearing such inscriptions as “Gov. Fuller, is your conscience clear, have you examined the report of your advisory committee?”, “Sacco and Vanzetti must not die!”, “Is Justice dead in Massachusetts?”, “Has the Cradle of Liberty become the arc of tyranny?”. The effect of our appearance on the Common thus armed was instantaneous. There was little time given us to speculate about our reception. The preparations Boston had been put to, had a use value, and Bostonians were eager to measure its extent. Cheers mingled with boos, curses with words of sympathy, hand claps with cat calls, and then the first delegation of the reception committee, the mounted cossacks, charged down upon our line. One gently ran his fingers down my back, and lifting me off my feet, tenderly, yet in unmistakable terms of welcome, said, “You are the first nigger anarchist I ever saw. Just think of a n***r bastard a Bolshevik!” The placard was torn from my hands and destroyed, and I was marched to a patrol wagon which had been kept waiting at the Tremont Street entrance of the Common for those of Boston’s visitors who had the temerity to comment upon her dishonor. There I was greeted by one of my comrades who had also been gathered in by the reception committee. She was assisted into the wagon, then one of our guardians said, “We can’t put the nigger in the Wagon with a white woman, we will let him ride outside.” And there I rode to the building prepared to receive me, the ante-chamber of the house of Liberty.

They Won’t Eat Crow by James Rorty.

“There are people in the world who will never eat crow. They will die or kill first.”

An old friend, a native New Englander who has lived in the vicinity of Boston for thirty years, offers this explanation of the Sacco-Vanzetti executions.

The interpretation seems plausible—more plausible than the theory, to which some of our liberal journals still cling, that Lowell, Stratton, and Grant signed a statement which fudged and distorted a legal record as crookedly as any hired shyster would have done it and yet remain honorable and sincere gentlemen.

I think my friend is right. The gentlemen just weren’t men enough to eat crow. Instead they killed with a public deliberateness which has shocked and amazed the world. Now it remains for them to die, spiritually very soon, and ultimately of course in the flesh.

With the pack behind them they had just courage enough to kill, much as a sadistic old man continues to beat his child, to prove to his outraged neighbors that he is master in his own home.

They were so poor in spirit, even in simple physical gallantry, that they couldn’t afford to confess how stupid, how terror-stricken they and their whole community of “respectables” had become.

How they must envy those two obscure Italians who remained so vibrantly true to themselves, who soared while they wallowed, and who at the last came to regard their slayers with simple wonderment and pity!

I don’t believe that Sacco and Vanzetti died for anarchy. I doubt that these brave deaths will appreciably nourish the sick body of the labor movement. I think Sacco and Vanzetti, victimized by a chain of circumstances in which one almost reads the hand of fate, died for the honor and truth of humanity. They died to show the world once more the power and beauty which is given to men who steadfastly love something more than themselves. They died well, and for us who have suffered too much and too long from the spiritual ineptitude, the shoddy greed and cowardice of our America, there is healing and power in those deaths.

There remains a task: to hunt cowardice in high places; to redeem the mortgaged code of truth and gallantry by which alone men can live together on the earth. Let’s get on with the task.

Swamps Stink by Grace Lumpkin.

Last summer a southerner who has lived in Boston for the past seven years said, “It is a privilege to rest in such an atmosphere of broadness. Such a center of culture tends to make the whole nation broader and finer.”

Down in South Carolina we had a jingle that began like this:

The River Saluda

Salutes the Broad River.

and we played in the swamps made by the broadening of these rivers. The gnarled old trees were fascinating in their decay and the green gray moss hanging down from twisted limbs. But swamps stink. We couldn’t play very long.

Sunday afternoon, the twenty-first of August, on Boston Commons the municipal band played Nearer My God to Thee while the police clubbed workers down near the gates. A Christian Scientist murmured: “It is terrible to bring forth this error of strife in human souls, but I see both sides and I know the Lord will bless all concerned.”

During the evening of August twenty-second the Baptist Babbit in the State House welcomed all petitioners with Christian breadth of mind,—and with a Christian’s devotion to duty stayed in his office until after twelve when, his work, for the day being over, he entered his closely guarded limousine and drove to his summer home like a snake crawling home through the bog. While the Baptist Governor sat in his chair in the State House,—out in Charlestown it was quiet—and dark. We had crossed the bridge, and were in the shadow of the buildings at the corner of two narrow streets. The air quivered with death. Across black houses, the only light that showed was a soft gleam, like a jack-o-lantern hovering over swamp death. Outlined by the light we saw a huge coffin shaped bulk, its base sunk into the general shadow—Charlestown jail and the death house.

Once, in South Carolina, while we were driving through the swamps late at night we saw a gang of men get out of a wagon and carry a coffin into the woods close by. While we waited for the men to go, the coffin was sucked down by the broad waters of the swamp.

Vindication Futile by Arturo Giovannitti.

There is only one thing more futile than to protest in behalf of martyrs, and that is to attempt to vindicate them. In the particular case of Sacco and Vanzetti, the only world which they loved and respected is satisfied with their innocence and needs no additional proof of it. The other world is the world which assassinated them, and surely they have no further reason for wanting to convince it of wrong.

Let them rest in peace; do not stir their ashes to prove that Judge Thayer was a bloody knave and Governor Fuller a heartless imbecile. Do not belittle their tragedy to make it serve so inconsequential an end. Their lives were too high a price to pay for the useless purpose of disturbing an evening at the club or an afternoon on the links of two estimable gentlemen whose remorse—should they be capable of it—is already provided for and condoned in advance by the salaries and the honors they get and by the assumption that the law is an abstract and impersonal force.

Sacco and Vanzetti were two inexorable enemies of that society of which the Thayers and the Fullers and the Lowells are the pillars and the props. They died like two soldiers in battle, or were killed like two hostages of war. It is useless to vindicate such men. Anarchists, like all true rebels, have no souls to save, anyway, and no reputation to rescue. The only important thing is the war. Renew the battle, and march on.

“A Million Men” by Clarina Michelson.

Boston is like a stagnant pool with a Book of Etiquette beside it. There are many things Bostonians do not think about, among them the Sacco-Vanzetti case. They feel they do not need to think or know about it. They bow humbly and reverently before Authority. Governor Fuller and President Lowell—one of the Lowells—neither of them crazy radicals, thank God, or foreigners. Authority and Good Form. After all, those are the only things that really matter. Well, of course, the children must be kept well, and your husband get to business on time. I always think if you live by the sea, it is wise to spend a month in the mountains. When we murder, you must admit we do it politely. The great gods Authority and Good Form have wiped out thoughts and feelings. Boston is like a stagnant pool. The only alive thing is Vanzetti’s voice from over the wall; “Organize a million men!”

The needle trades workers of Boston know what it’s all about. They know that Sacco and Vanzetti are going to be murdered tonight because they are workers, because they are radicals and because they are foreigners. They know, with Sacco, that all the petitions, all the cables, all the telegrams, and all the last hurried visits of respectables and intellectuals will not stir Fuller one hundredth of an inch from his place in the capitalist class. A strike-breaker for President; why should a Governor be untrue to his class? They know that the voice of the American workers shouting “Sacco and Vanzetti shall not die!” is not yet loud enough. And they know, with Vanzetti, what must de done; Organize a million men, and again a million.

Death House by Joseph Lilly.

It is difficult sensibly to attach a meaning to the set of a man’s mouth, to the stare of his eyes, the tilt of his head, as he walks to his certain death. But it is easy to say now that on Sacco’s face these marks meant eagerness. It is easy to say it now because he said it as he sat down.

“Viva anarchia!” He said it, rather, blurted it, as two keepers, utterly unperturbed, hastily strapped the spongy electrodes to his shins. Before the executioner, among whose duties is that of applying the death cap, moved furtively from behind, Sacco said something else.

“Farewell, my wife and child,” he said, his voice much lower, but still steady. “Good evening, gentlemen. Farewell mother.”

* * *

The witnesses didn’t look to see Vanzetti, but he looked at them, interestedly, curiously, bravely.

He looked up to the bright electric light directly over the chair, and to the noxious smoke circling about it, and then he recognized the Warden. He shook hands with the Warden. He shook the hand of one guard, then another, and then, calmly, he sat down.

“I wish to tell you I am innocent,” he said. “I never committed any crime,—but sometimes some sins. I thank you for everything you have done for me. I am innocent of all crime, not only this one, but all. I am an innocent man.”

He paused so as not to inconvenience the executioner while he fitted on the death cap.

“I wish to forgive some people for what they are doing to me.”

Those were his last words. They were hardly uttered when the Warden, with the slightest nod of his knobby head, signaled the end. The generator whirred again, the sparks dangled over the death cap, the smoke around the electric light became darker.

They Will Remember by William Gropper.

There stands on a street in Boston a huge clock with two black hands. I shall always remember it as the death clock, for there I with many others waited for the hour of twelve. Our eyes were lifted to that clock with its two black hands, and in terror we watched a hand crawl slowly towards the deadly middle with the Roman numerals. And then the clock struck and I heard someone beside me count slowly from one t( twelve. He counted, and in that simple count I heard twelve little death songs. And soon on a board near us appeared the words, sacco, vanzetti DEAD. Then nothing mattered, nothing except the morrow…for I knew the workers would remember.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1927/v03n06-oct-1927-New-Masses.pdf