Within months of assuming power in an exhausted and shattered country, food became the central issue of the Revolution. Lenin responds not only as a Bolshevik, but as leader of a new state, to the beginnings of what would be several famines killing hundreds of thousands as a civil war raged in a blockaded country. Published in Pravda on May 24, 1918, the letter points to what would become known as ‘War Communism.’

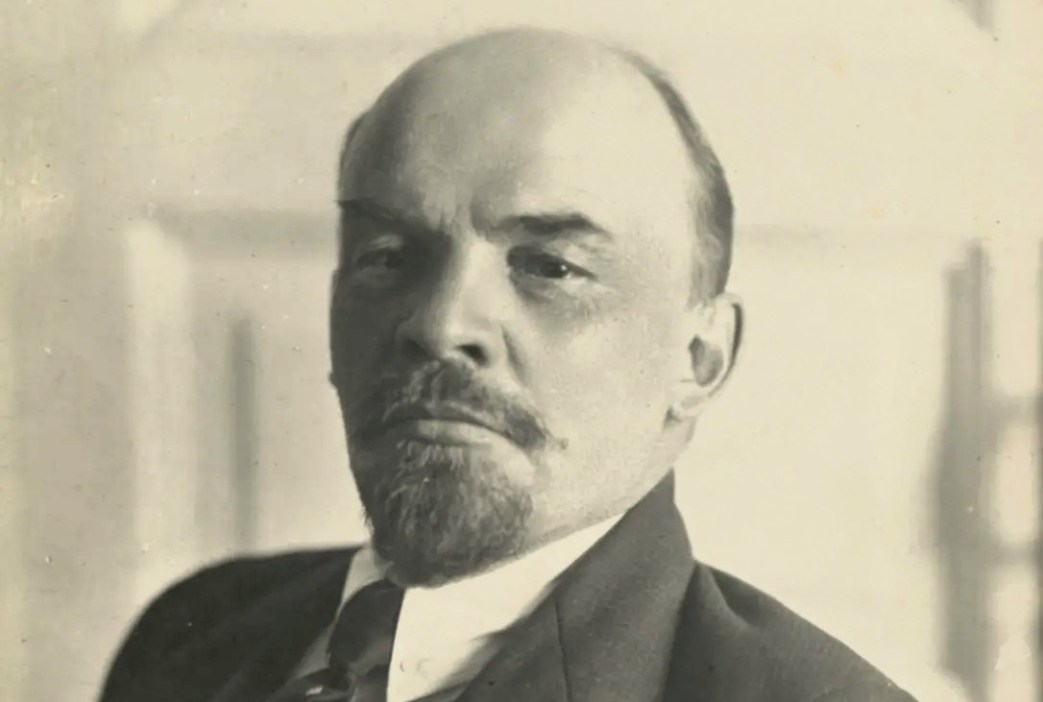

‘The Famine: A Letter to the Workers of Petrograd’ (1918) by V.I. Lenin from Selected Works, Vol. 8. International Publishers, New York. 1929.

COMRADES,

The other day I received a visit from your delegate, a Party comrade, a worker in the Putilov Works. This comrade drew a detailed and extremely painful picture of the food shortage in Petrograd. We all know that the food situation is just as acute in a number of the industrial gubernias, and that starvation is knocking just as menacingly at the door of the workers and the poor generally.

And side by side with this we observe a riot of profiteering in grain and other food products. The food shortage is not due to the fact that there is no bread in Russia, but to the fact that the bourgeoisie and the rich generally are putting up a last decisive fight against the rule of the toilers, against the state of the workers, against the Soviet government, on this most important and acute of questions, the question of bread. The bourgeoisie and the rich generally, including the village rich, the kulaks, are doing their best to thwart the grain monopoly; they are dislocating the distribution of grain undertaken by the state for the purpose of supplying bread to the population, and particularly to the workers, toilers and needy. The bourgeoisie are violating the fixed prices, they are profiteering in grain, they are making a hundred, two hundred and more rubles profit on every pood of grain; they are undermining the grain monopoly and the proper distribution of grain by resorting to bribery and corruption and by maliciously supporting everything tending to destroy the power of the workers, which is endeavouring to put into effect the prime, basic and root principle of socialism: he who toils not, neither shall he eat.

He who toils not, neither shall he eat—this is comprehensible to every toiler. Every worker, every poor peasant, even every middle peasant, everybody who has suffered need in his lifetime, and everybody who has ever lived by his own toil, is in agreement with this. Nine-tenths of the population of Russia are in agreement with this truth. In this simple, elementary and obvious truth lies the basis of socialism, the indestructible source of its strength, the indelible pledge of its final victory.

But the whole point of the matter is that it is one thing to signify one’s agreement with this truth, to swear that one professes it, to give it verbal recognition, but it is another to be able to put it into effect. When thousands and millions of people are suffering the pangs of hunger (in Petrograd, in the non-agricultural gubernias and in Moscow) in a country where millions and millions of poods of grain are being concealed by the rich, the kulaks and the profiteers—in a country which calls itself a socialist Soviet republic—there is matter for the most serious and profound thought on the part of every enlightened worker and peasant.

He who toils not, neither shall he eat—how is this to be put into effect? It is as clear as daylight that in order to put it into effect we require, firstly, a state grain monopoly, i.e., the absolute prohibition of all private trade in grain, the compulsory delivery of all surplus grain to the state at a fixed price, the absolute prohibition of all withholding and concealment of surplus grain, no matter by whom. Secondly, we require the strictest registration of all grain surpluses and the irreproachable transport of grain from places of abundance to places of shortage, and the creation of reserves for consumption, for industrial purposes and for seed. Thirdly, we require a just and proper distribution of bread, controlled by the workers’ state, the proletarian state, among all the citizens of the state, a distribution which shall permit of no privileges and advantages to the rich.

One has only to reflect ever so slightly on these conditions for ending the food shortage to realise the abysmal stupidity of the contemptible anarchist windbags, who deny the necessity of a state power (and of a power which will be ruthless in its severity towards the bourgeoisie and ruthlessly firm towards disorganisers) for the transition from capitalism to communism and for the emancipation of the toilers from all forms of oppression and exploitation. It is at this moment, when our revolution is directly tackling the concrete and practical tasks involved in the realisation of socialism—and that is its indefeasible merit—it is at this moment, and in connection with this most important of questions, the question of bread, that the necessity becomes absolutely clear for an iron revolutionary government, for the dictatorship of the proletariat, for the organised collection of products, for their transport and distribution on a mass, national scale, a distribution which will take into account the requirements of hundreds of millions of people, which will take into account the conditions and the results of production for a year and many years ahead (for there are sometimes years of bad harvest, there are methods of land improvement for increasing grain crops which require years of work, and so forth).

Romanov and Kerensky left as a heritage to the working class a country utterly impoverished by their predatory, criminal and most burdensome war, a country picked clean by Russian and foreign imperialists. Food will suffice for all only if we keep the strictest account of every pood, only if every pound is distributed absolutely systematically. There is also an acute shortage of food for machines, i.e., fuel: the railroads and factories will come to a standstill, unemployment and famine will ruin the nation, if we do not bend every effort to establish a ruthless economy of consumption and proper distribution. We are faced by disaster, it has drawn terribly near. An intolerably severe May will be followed by a still more severe June, July and August.

Our state grain monopoly exists in law, but in practice it is being thwarted on every hand by the bourgeoisie. The rural rich, the kulak, the parasite who has been robbing the whole neighbourhood for decades, prefers to enrich himself by profiteering and illicit distilling; that, you see, is so advantageous for his pocket, while he throws the blame for the food shortage on the Soviet government. In the same way are acting the political defenders of the kulak, the Cadets, the Right Socialist-Revolutionaries and the Mensheviks, who are overtly and covertly “working” against the grain monopoly and against the Soviet government The party of spineless individuals, i.e., the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries, are displaying their spinelessness here too: they are giving way to the covetous howls and outcries of the bourgeoisie, they are crying out against the grain monopoly, they are “protesting” against the food dictatorship, they are allowing themselves to be intimidated by the bourgeoisie, they are afraid to fight the kulak, and are hysterically tossing hither and thither, recommending that the fixed prices be raised, that private trading be sanctioned, and so forth.

This party of spineless individuals reflects in politics very much of what takes place in ordinary life when the kulak incites the poor peasants against the Soviets, bribes them by, say, giving some poor peasant a pood of grain not for six, but for three rubles, so that the poor peasant, thus corrupted, may himself “profit” by speculation, himself make a “deal” by selling that pood of grain at a profiteering price of one hundred and fifty rubles, and himself become a decrier of the Soviets, which have prohibited private trading in grain.

Whoever is capable of reflecting, whoever is desirous of reflecting ever so little, will see clearly what line this fight has taken.

Either the advanced and enlightened workers triumph and unite around themselves the poor peasant masses, establish rigid order, a mercilessly severe government, a genuine dictatorship of the proletariat—either they compel the kulak to submit, and institute a proper distribution of food and fuel on a national scale; or the bourgeoisie, with the help of the kulaks, and with the indirect support of the spineless and mentally confused (the anarchists and the Left-Socialist-Revolutionaries), overthrow the Soviet power and set up a Russo-German or a Russo-Japanese Kornilov, who will present the people with a sixteen-hour working day, one-eighth of a pound of bread per week, mass shooting of workers and jail tortures, as has been the case in Finland and the Ukraine.

Either—or.

There is no middle course.

The situation of the country is desperate in the extreme.

Whoever gives a thought to political events cannot but see that the Cadets are coming to an understanding with the Right Socialist-Revolutionaries and the Mensheviks as to who would be “pleasanter,” a Russo-German or a Russo-Japanese Kornilov, as to who would crush the revolution more effectively and reliably, a crowned or a republican Kornilov.

It is time all enlightened and advanced workers came to an understanding. It is time they pulled themselves together and realised that every minute’s delay may spell ruin to the country and ruin to the revolution.

Half-measures are of no avail. Complaining will lead us nowhere. Attempts to secure food and fuel “in a retail fashion,” i.e., every factory, every workshop for itself, will only increase the disorganisation and assist the avaricious, filthy and dastardly work of the profiteers.

That is why, comrades workers of Petrograd, I have taken the liberty of addressing this letter to you. Petrograd is not Russia. The Petrograd workers are only a small part of the workers of Russia. But they are one of the best, most advanced, most class conscious, most revolutionary, most steadfast detachments of the working class and the toilers of Russia, and the least liable to succumb to empty phrases, to weak-willed despair and to the intimidation of the bourgeoisie. And it has frequently happened at critical moments in the life of a nation that even small but advanced detachments of advanced classes have drawn the rest after them, have fired the masses with the spirit of revolutionary enthusiasm and have accomplished tremendous historic feats.

“There were forty thousand of us at the Putilov Works,” the delegate from the Petrograd workers said to me. “But the majority of them were ‘temporary’ workers, not proletarians, unreliable, flabby individuals. Fifteen thousand are now left, but these are proletarians, tried and steeled in the fight.”

This is the sort of vanguard of the revolution—in Petrograd and throughout the country—that must sound the call, that must rise in their mass, that must understand that the salvation of the country is in their hands, that from, them is demanded a heroism not less than that which they displayed in January and October 1905 and in February and October 1917, that a great “crusade” must be organised against the food profiteers, the kulaks, the parasites, the disorganisers and the bribers, a great “crusade” against the violators of strict state order in the collection, transport and distribution of food for the people and food for the machines.

The country and the revolution can be saved only if the advanced workers rise en masse. We need tens of thousands of advanced and steeled proletarians, enlightened enough to explain matters to the millions of poor peasants all over the country and to assume the leadership of these millions, tempered enough to cast out of their midst and to shoot all who allow themselves to be “tempted”—as indeed happens—by the temptations of profiteering and to be transformed from fighters for the cause of the people into robbers, steadfast enough and devoted enough to the revolution to bear in an organised way all the hardships of the crusade into every corner of the country for the establishment of order, for the consolidation of the local organs of the Soviet government and for the exercise of control in the localities over every pood of grain and every pood of fuel.

It is far more difficult to do this than to display heroism for a few, days without leaving the place one is accustomed to and without joining the crusade, and by confining oneself to a spasmodic insurrection against the idiot monster Romanov, or the fool and braggart Kerensky. Heroism displayed in prolonged and stubborn organisational work on a national scale is immeasurably more difficult than, but at the same time immeasurably superior to, heroism displayed in an insurrection. But it has always been the strength of working class parties and of the working class that they courageously and directly look danger in the face, that they do not fear to admit danger and soberly weigh the forces in their own camp and in the camp of the enemy, the camp of the exploiters. The revolution is progressing, developing and growing. The problems that face us are also growing. The struggle is broadening and deepening. Proper distribution of food and fuel, their procurement in greater quantities and their strict registration and control by the workers on a national scale—that is the real and chief approach to socialism, that is not so much a revolutionary task in general as a communist task, one of the tasks on which the toilers and the poor must offer determined battle to capitalism.

And it is worth devoting all one’s strength to such a battle; its difficulties are immense, but the cause of the abolition of oppression and exploitation for which we are fighting is also immense.

When the people are starving, when unemployment is becoming ever more menacing, anyone who conceals a surplus pood of grain, anyone who deprives the state of a pood of fuel is an out-and-out criminal.

At such a time—and for a truly communist society this is always true—every pood of grain and fuel is veritably sacred, much more so than the sacred things used by the priests to confuse the minds of fools, promising them the kingdom of heaven as a reward for slavery on earth. And in order to relieve this genuinely sacred thing of every remnant of the “sacredness” of the priests, we must take possession of it practically, we must achieve its proper distribution in practice, we must collect the whole of it without exception, every particle of surplus grain must be brought into the state reserves, the whole country must be swept clean of concealed or ungarnered grain surpluses, we need the firm hand of the worker to harness every effort, in order to increase the output of fuel and to secure the greatest economy and the greatest efficiency in the transport and consumption of fuel.

We need a mass “crusade” of the advanced workers to every centre of production of grain and fuel, to every important centre where grain is transported and distributed; a mass “crusade” increase the intensity of work tenfold, to assist the local organs of the Soviet government in the matter of registration and control, and to destroy profiteering, bribery and disorderliness by armed force. This is not a new problem. History in fact is not creating new problems—all it is doing is to increase the size and scope of the old problems as the scope of the revolution, its difficulties and the dimensions of its historic aims, increase.

One of the great and ineradicable features of the October Revolution—the Soviet revolution—was that the advanced worker, as the leader of the poor, as the captain of the toiling masses of the countryside, as the builder of the state of the toilers, went among the “people.” Petrograd and other proletarian centres have given thousands and thousands of their best workers to the countryside.

The detachments of fighters against Kaledin and Dutov, and the food detachments, are not new. The whole thing is that the proximity of disaster, the acuteness of the situation compel us to do ten times more than before.

When the worker became the vanguard leader of the poor he did not thereby become a saint. He led the people forward, but he also became infected with the diseases of petty-bourgeois disintegration. The fewer the detachments of best organised, of most enlightened and most disciplined and steadfast workers were, the more these detachments tended to degenerate, the more frequently the petty-property instincts of the past triumphed over the proletarian-communist consciousness of the future.

The working class has begun the communist revolution; but it cannot instantly discard the weaknesses and vices inherited from the society of landlords and capitalists, the society of exploiters and parasites, the society based on the filthy cupidity and personal gain of a few and the poverty of the many. But the working class can defeat the old world—and in the end will certainly and inevitably defeat the old world—with its vices and weaknesses, if against the enemy are brought ever greater and more numerous detachments of workers, ever more enlightened by experience and tempered by the hardships of the struggle.

Such is the state of affairs in Russia today. Single-handed and disunited we shall never put an end to hunger and unemployment. We need a mass “crusade” of advanced workers to every corner of this vast country. We need ten times more iron detachments of the proletariat, enlightened and unreservedly devoted to communism. Then we shall triumph over hunger and unemployment. Then we shall advance the revolution to the true gates of socialism and then too we shall be in a position to conduct a triumphant war of defence against the imperialist plunderers,

May 1918.

International Publishers was formed in 1923 for the purpose of translating and disseminating international Marxist texts and headed by Alexander Trachtenberg. It quickly outgrew that mission to be the main book publisher, while Workers Library continued to be the pamphlet publisher of the Communist Party.

PDF of original book: https://archive.org/download/vileninselectedwviiivari/vileninselectedwviiivari.pdf