Itinerant wobbly Nils Hansson with a classic account of two years’ experience riding the rails, seeking work, organizing his fellow wage-slaves, and going to jail from Los Angeles to Yuma, through El Paso to New Orleans, up to Chicago and New York, then back to California.

‘The Promised Land of Work: Seeing America First’ by Nils H. Hansson from International Socialist Review. Vol. 15 No. 6. December, 1914.

IN these historical days there is a great howl going the rounds of the American press about “seeing America first.” Of course, it is the tourists who go to France or Germany or England to spend their parasitical days to whom they refer and not by any means those useful members of society in overalls—the producing class.

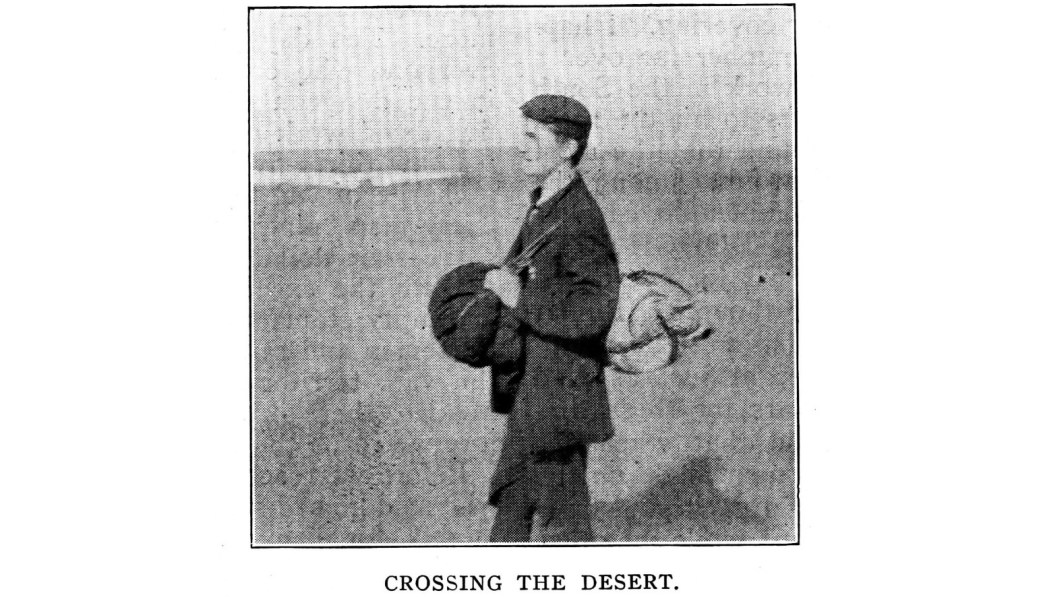

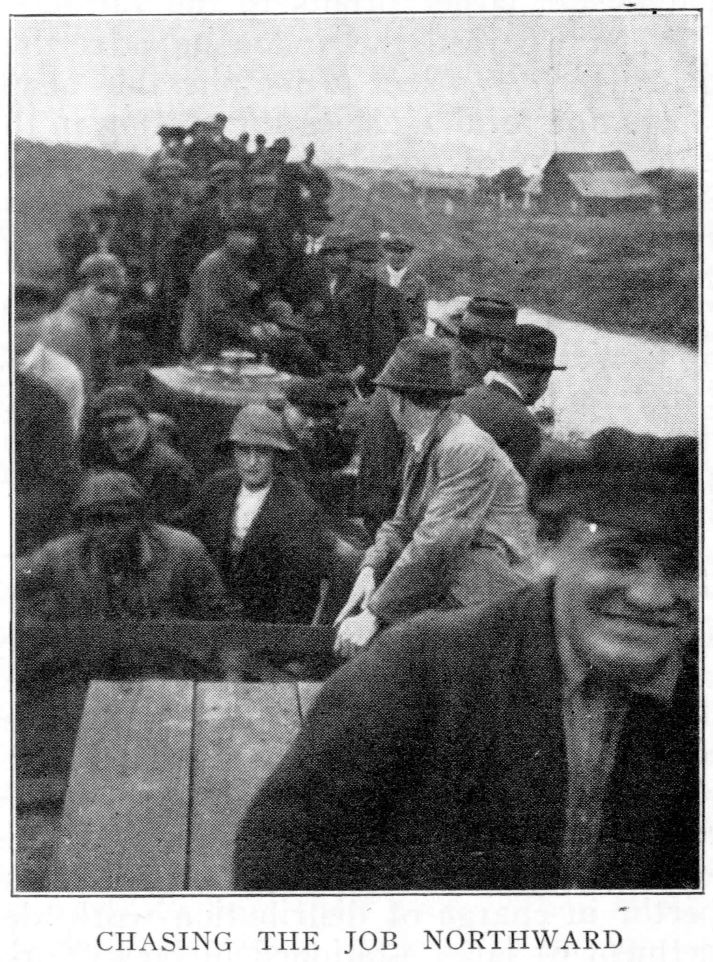

The only land useful folks usually see is their native country—and they rarely get outside of a twenty-mile square in it in their lifetime. Of course, there are many of us who are given the opportunity (though not the MEANS) to see America. We are the migratory workers who are floating from one part of the country to another, always looking for the Almighty Job.

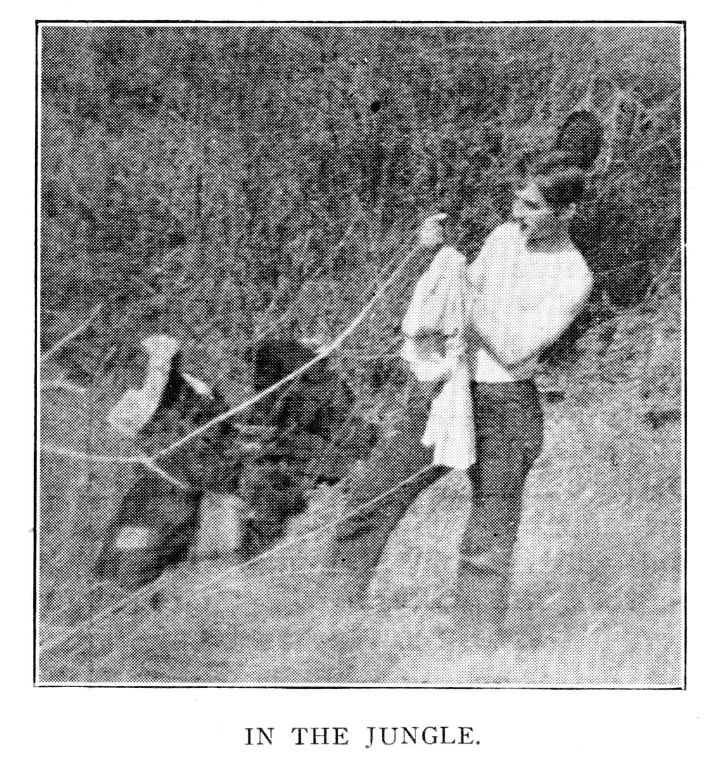

We certainly do “see America”, not generally because we like to, but because society forces us to do so. There are always rumors reaching our ears that the next place, or the next city, may be better. So that we are ever drifting into strange territories lured by the hope of work. Ahead of us lurk the dangers of “the road.”

For the past two years I have been one of this kind of tourists and I will try to tell you of some of the wonderful sights my eyes have seen in this glorious Land of Liberty (?).

Six Doughnuts in “Los”

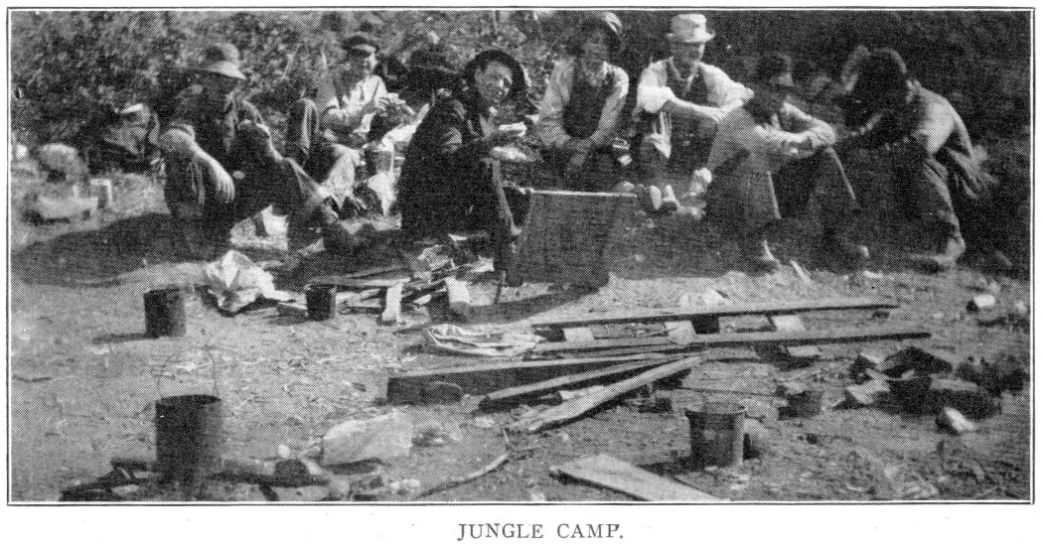

Last December a small unemployed army marched here and there through California, making from eight to twenty miles-a day carrying their bundles on their backs. It was a raggedy little bunch of slaves who had united for the purpose of getting a little to eat and, perhaps, a leaky old warehouse to sleep in. Often, however, the sky was their roof and the rain was their covering. I happened to be of their number for over a week, but the lure of work in the South led me and many others to hit the road.

In Los Angeles I found that the most popular word passed around among the tens of thousands of unemployed was, that you could get SIX DOUGHNUTS and a CUP OF COFFEE for: five cents: God, such a heaven! I thought. But at the same time if one has not the requisite five cents they might just as well have made it five dollars for these lifesavers. There I found that when the available funds of two men made up the required sum, one would go in and have coffee and two doughnuts while the other waited outside for FOUR doughnuts and no coffee. They were both saved for the time being. Then they took turns begging another nickel for the next day’s provisions. And each nickel was hard to get although Los Angeles was supposed to be a “good town.”

The winters are tolerably warm in “Los,” though I have seen a quarter of an inch of ice on the ponds around there. So do not imagine it is a real paradise to sleep outside with a “California blanket” (a newspaper and gunnysack) for shelter. But it is so warm in the day and one’s blood is so thin that the nights FEEL like thirty below zero weather.

I wish the tourist parasites traveling through California might see the thousands of hungry men whose busy hands have made it possible for them to “see America” and to live in luxury. A bluelipped “bum” might spoil the whole picture.

Last winter “Los” had an extra police force for the purpose of arresting all persons who happened to land in town at night or who resembled some “undesirable.” After I had spent one night in their filthy jail it was sixty days or leave town for me.

The Hoboes’ Paradise

Yuma, Arizona, was the next point to stand out for especial interest. It used to be called “The Hoboes’ Paradise” because it is the warmest place in America. So, many who have not warm clothing and no chance to get it, tried to keep around there in winter time. Not so any more. Ten days is what is handed to everyone who comes through—ten days in the dungeon on bread and water or five days’ work on the rockpile.

I saw thirty-five men arrested there on a charge of vagrancy in one night. For every man “pinched” the police get their share—one dollar a head.

With the exception of long walks on an empty stomach, the dangers of brutal brakemen and railroad police all through the vast territory of Arizona and New Mexico, there-is not much to relate before we reach the city of El Paso, Texas.

Before we reached there we met a man who said he had served two hundred days merely for being found on the streets at night without the price of a bed. His face told the same story. He said that before he reached El Paso he was strong and healthy, but when we saw him there was not much left of him. Consumption was eating his life out very fast. He said that when you look up at the sun for a moment from the El Paso rockpile, there is always a black-jack or a pickhandle ready for you.

Shackles and Chains

Before we arrived in El Paso my partner and I suggested that we remain outside the city till daylight. But the third in our party, whom we had picked up on the road, an elderly man, urged us to go on and take a room for the night. “They won’t arrest us workingmen,” he said. And as he had money and was going to pay for us, we allowed ourselves to be persuaded.

We had not walked two blocks before we were approached by two detectives who had searched the freight we came in on, and in a most decisive manner we were taken to the police station.

Finding no guns upon us and only four dollars (belonging to the old fellow who thought they would not “arrest workingmen”) we were let into the kennel. It was a filthy room about 60 by 30 feet. On each side were about eight cells running one-third the way up to the ceiling. On top of each cell and everywhere on the cement floor were crowded men of our type—most of them serving their time or waiting for what the judge would hand out to them in the morning.

The night was chilly and there were no blankets—only a few rags and not half-enough of them. A couple of drunks were howling in the cells and disturbing those who had done a hard day’s work on a Texas rock pile.

At about 5 o’clock the Get-up signal was given and there was a hurrying and scraping of feet and a “reading of shirts” before they were put on. Five dope fiends were in the bunch. One, a miserable little creature with eyes sticking out, hair standing erect and back bent because of “the habit,” cried out at the door, “Say, Captain, can’t I have a little medicine?” The door was opened and for answer he received a chair on the head with a promise of death if he asked for dope again.

“Line up for breakfast” was the next order and inside a second we were all in line. Some discipline there! A few beans, some bread and weak coffee were given us, which, by the way, was very welcome to our party, as we had had little to eat for two days. A few minutes later a tough-looking individual entered carrying a big Texas hat in his hand. He was guard at the rock pile.

“Line up, chain gang,” was his greeting as he came in, and it wasn’t said in a friendly way, either. They lined up faster than I can tell it. I never saw anybody move as fast as those slaves in the El Paso jail. We were given a hint to climb up on top of the cells if we didn’t want to get “sapped up.”

One by one the men, whose crime was lack of work, put on their chains and fastened their shackles, each shackle locked to the leg with a big padlock. To assure the fastening, a small steel bar was used to test each lock. Not much time was lost in assuming the chains. All worked swiftly like a machine.

In that chain gang were three Mexican boys between the ages of eleven and thirteen bearing the heavy chains and shackles. One man was beaten into unconsciousness because he said “I am sick and cannot work.”

I happened to land in New Orleans just before the Mardi Gras celebration, when all strangers are herded in or fined $2.00. The police are in evidence everywhere, but I learned how to avoid them and they did not get me there.

Leaving filthy New Orleans and the Dark South with its small shacks without doors or windows, its ragged men and women, its whipping of boys and negroes, we will proceed on our “journey.” Next stop, Kansas City, Mo. The Helping Hand In that great Missouri town the authorities have “solved the problem” of the unemployed in their Helping Hand (?) Institute. There all suckers. are given a chance to make “coffee and,” even in the Winter. Instead of using a rock crusher the men break rocks by hand. You get five cents a box for breaking rocks—and a big box at that. Three boxes pay for a meal at the H. H. Evidently if we only abolish the new machinery there will be work for everybody. The men seem glad to work all day for a bed and a couple of scanty meals.

I don’t think you could ever use the Western workers in this way. They are too rebellious and too intelligent. They might use a little direct action where the commodities they produced are piled up.

Breadlines

Next point, Chicago. It was almost snowing and the March winds were blowing hard when I ran against the bread line at Union and Randolph street. I failed to see the healthy faces one finds in the West. Everybody looked pale and sickly. Surely, I thought, these men don’t know how to get chicken or how to cook “mulligan.” They stood there shivering, waiting for the doors of the Municipal Lodging House to open.

We were roundly questioned and finally given a ticket for eats and a bed—more than a thousand of us, when the man just ahead of me fell to the floor in a lifeless condition. He was taken away and the report was that he was almost starved to death.

Everybody carried a newspaper and I wondered why. I found out later. We were given a piece of stale bread about two inches thick and a cup of watery coffee and they seemed to like it, too.

We walked up to the third floor, passing two on the way, already filled with the jobless. Each floor was one huge room where five hundred men were piled in on the floor like sardines in a box.

The whistle for rising blew at 5 o’clock and there was a hasty search for vermin through the room. Out we marched and were given more bread and coffee (?) when we were turned out into the cold. No chance to wash or bathe was given us. The windows were kept closed. You can imagine how thick the air was.

There are societies and societies for fighting tuberculosis, but what good are they when diseased men are thrown in with well ones as we were here?

Chicago has a five-cent “flop” where some thousands are lodged and many ten and fifteen-cent lodging houses.

Many of the men I met here in the Breadline seemed not to desire or hope for anything at all. They were so weak in mind and body that they had lost all spirit of rebellion. Day and night they slunk in to warm corners in the chance that there might be “free shipping” to some better point. Of work in Chicago most of us found none.

After a few days in New York, I left the East and its Breadlines, the South with its prejudices and brutalities and went back to the Pacific Coast after a few more experiences with the railroad police. Now I hear that the unemployed here are organizing to defy the drones higher up; that they are refusing to eat soup and swill—these men who have produced EVERYTHING and are starving and shelterless because of the profit system of today.

Thousands already are sleeping in the San Francisco parks in the daytime and walking the streets at night. Others are “hitting” back doors and “bumming” on the street for the price of something to eat.

If some of those who talk about “seeing America first” realized that in Virginia and West Virginia between those beautiful mountains are men and women, who, when they ask for bread are given cold lead instead; the picture might. lose some of its charm.

When we see the hundreds of thousands of children wearing their lives away in the cotton mills, the lovely colors fade away. There are so many things, rude things, crude things in the background.

See America first! See the picturesque hills of Colorado—and the starving miners where bloody Ludlow stares you in the face., Travel through the sunkissed valleys of California, and murderous Wheatland, San Diego and the pickhandle administration against the unemployed rob the scenes of their attraction.

Large sums of money are being spent upon the World’s Fair with its wondrous buildings shimmering against the smiling sun over the Golden Gate. I wish that the thousands of hungry men and women out of work could stand at the entrance to show just what all this splendor really means.

Wherever you go it is much the same. East, West, North, South—misery beyond description, black-jacks, chain gangs, jails and pens, and shackles for those who dare tell about them.

And it will always be so until those hungry beasts of burden awaken to their power, arise and unite to take back what they have produced!

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v15n06-dec-1914-ISR-riaz-ocr.pdf