An introduction to the background of Britain’s enviably rich workers’ education tradition with a look at the Plebs’ Leagues.

‘The British Labour College Movement’ by J.F. Horrabin from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 4 No. 13. February 21, 1924

There is no need to remind students of social history that the most significant social factors are not always those most widely advertised. And what is true of society in general is true also of the working-class movement itself. It is all too easy often–indeed, it is almost inevitable–to judge of the character and strength of any particular section of that movement from its platform orators, its leader-writers, its Trade Union negotiators, and all those other figures (or “figure-heads”) who, by superficial observers, are accepted not only as representing, but as actually typifying, the personnel of the movement at large. Generalisations based on such slender evidence are unsafe guides–either for action or for criticism.

One of the most significant facts in the “inside” history of the British Labour Movement during recent years has been the striking growth of the demand, by the rank and file of the movement, for Education in the Social Sciences; for a grounding, that is, in the broad facts of History and Education, studied from the working-class point of view. Yet the Labour College Movement which has grown up as a result of that demand is by no means as yet widely known–and that despite the fact that the Times and the Morning Post have recently done what they could in the way of greater publicity!

From quite small beginnings, 15 years ago, the Labour College movement in England, Scotland and Wales has developed into a widespread national organization, with (this year) upwards of 17,000 students enrolled in its various classes. Most significantly, the whole movement–the original demand, and the machinery by which that demand has been met, has been, in the main, an entirely “rank and file” affair. Until quite recently none of the more prominent working-class leaders, political or industrial, have been identified with it. It had its origin in a quite spontaneous expression of “rank and file” opinion–a strike of Trade Union students undergoing training at Ruskin College, Oxford, an educational institution carried on with more or less “liberal” aims and standing definitely for the idea of social solidarity” so far as education was concerned. The Trade Unionists who supported this institution perceived no contradiction between this attitude and their own independent working- class action in political and industrial affairs. But the students who revolted (in the spring of 1909) realized the contradiction very clearly; and they were able to persuade a sufficient number of the members of their Trade Unions (chiefly railway-men and South Wales miners) to make possible the establishment of a resident college based on a recognition of “the antagonism of interests between Capital and Labour” and on the fact that this antagonism expressed itself, so far as educational matters were concerned, precisely in those subjects of most interest and importance to the workers: i.e., in all those subjects dealing directly or indirectly, with the structure of society and with “social problems”.

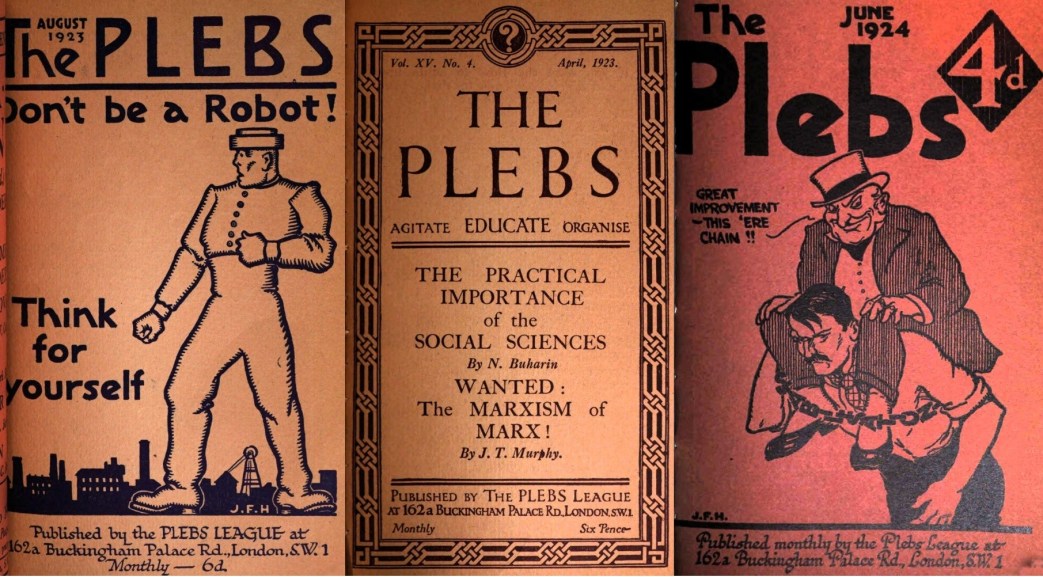

For the first four or five years the greater part the energies of those interested in the movement were directed towards keeping the Labour College in existence–and a very precarious existence it was at times! But during his same period, evening classes began to be established in various industrial centres–in Lancashire, Yorkshire, and South Wales, especially; while the Socialist Labour Party group, centred in Glasgow, were laying the foundations of a similar educational movement in Scotland. During all this time, the propagandist organisation established by the pioneers of the movement–the Plebs League–and its monthly organ, the Plebs Magazine, served as links between the different centres and gained fresh converts to the cause of Independent Working Class Education.

In 1914 the resident Labour College in London was definitely taken over by the two Unions–the National Union of Railwaymen and the South Wales Miners Federation sections–of whose members had from the first been its most active supporters; and from this year onwards, accordingly, the mass of the movement was able to concentrate on what, after all, was its most important aim–the establishment and development of the evening classes for workers up and down the country.

During the war years, despite the absence of many active workers in the army or in prison, this class-work increased by leaps and bounds. The existence of a rival organization in the field, the Workers Educational Association–which stood for the same ideas of “social solidarity” as Ruskin College had done, and which aimed at making ruling-class culture more accessible to the workers–made it possible for the whole of the Plebs propaganda to be conducted on a definitely class basis; and fought out–in Trades Councils and local Trade Union branches–as a definite class issue. It was the very essence of the movements’ slogan, Independence in Working Class Education, to force this question of working-class independence–i.e. of class–“consciousness all round”–into the forefront. The discussions which went on everywhere between the advocates of the two opposing points of view, had accordingly far more significance than a mere debate on educational problems pure and simple. On the one hand, the men of the Plebs Labour College group took their stand on the Marxian view of history, on Marxian economics, and on the need for the workers, starting from these bases, to develop their own “fighting culture” as a weapon in the class-struggle; on the other, the University-trained champions of the Workers’ Educational Association proclaimed that education was “above the battle”, that it was concerned chiefly with the “humanities”, based on eternal verities and unaffected by ephemeral things, like class distinctions, and that, even apart from the humanities, it was possible (and desirable) to teach quite impartially the fundamental truths about society and existing social systems, without any bias on the side either of capitalists or proletarians. It was impossible to conduct such an argument without raising basic questions about the very foundations and aims of the whole working-class movement. Labour College propaganda, accordingly, cannot be regarded as confined to a specialised field and as having, therefore, but minor reactions on the workers’ movement generally.

By 1921, the various class-centres had increased both in numbers and activities to such an extent that some more definite form of national organization was generally felt to be desirable; and in the autumn of that year a conference of representatives, convened by the Plebs League, decided on the formation of the National Council of Labour Colleges, now the central organization of the movement. It is composed of the Labour College, London (the only residential institution in the movement); the Scottish Labour College, co-ordinating the various districts in Scotland; over 70 local Labour Colleges, i.e. evening-class centres in different towns; the Plebs League, which enrols individual enthusiasts, and which serves as the publishing department of the movement; and of such national Trade Unions as inaugurate educational schemes for their members and make financial grants to the N.C.L.C. for this purpose. (The two most important of these are those established by the Building Trade Workers (A.U.B.T.W.) and the Distributive Workers (N.U.D.A.W.)) Very many Trades Councils; local Labour Parties, and Trade Union branches are affiliated to the local Colleges.

Last year, 1922-23, the number of students attending classes was just under 12,000. This year, as has already been stated above, that number promises to exceed 17,000. The great majority of the tutors are voluntary workers. But the support of the national Trade Unions has made it possible to establish whole-time organizers in the principal centres, and these men invariably act as tutors also.

Not only has the actual class movement been thus organized, but the equally important task of providing textbooks and other literature has been tackled. The Plebs League–which in addition to its monthly magazine–had previously issued short economic and historical text-books by W.W. Craik, Noah Ablett and Mark Starr, has during the last two years issued four volumes in a uniform textbook series. An Outline of Psychology (fourth edition now printing), An Outline of Imperialism, An Outline of Economics, and An Outline of Economic Geography (first edition of 5000 copies already nearly sold out within three months of publication). Each of these books was originally drafted by one hand, then discussed and revised by an editorial committee. In addition to them, several smaller books and pamphlets–including What to Read: A Guide to Books for Workers Students–have been issued by the League; as well as cheap “students’ editions” of such books as Philip Prices’ Reminiscences of the Russian Revolution, and R.W. Postgate’s Revolution, from 1789 to 1906. In the Plebs Magazine itself, of course, numerous short studies on economic, historical and geographical subjects are published.

The main problem which the Labour College movement is setting itself to solve–both as regards actual teaching and publications–is that of so simplifying and condensing the essential facts of History, Economics, and Social Theory, as to make practicable the provision of at least an elementary training in these subjects for the whole rank and file of the workers’ movement. This, under existing circumstances, is a more pressing problem than the carrying on of further research work, or the development of theory–though of course the two sides of the educational movement cannot be kept entirely separate. But the very weakness of the workers’ press in Britain, as compared with certain other countries, makes all the more necessary this “popularization” of the fundamental facts about society, from the working-class point of view, by means of educational machinery. The dangers of over-simplification, of “short cuts” to knowledge, must be faced and overcome. The need for a more widespread understanding, by proletarians, of the “whys and wherefores” of the proletarian position is obvious. It is that need which the British Labour College movement is trying to meet.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1924/v04n13-feb-21-1924-inprecor.pdf