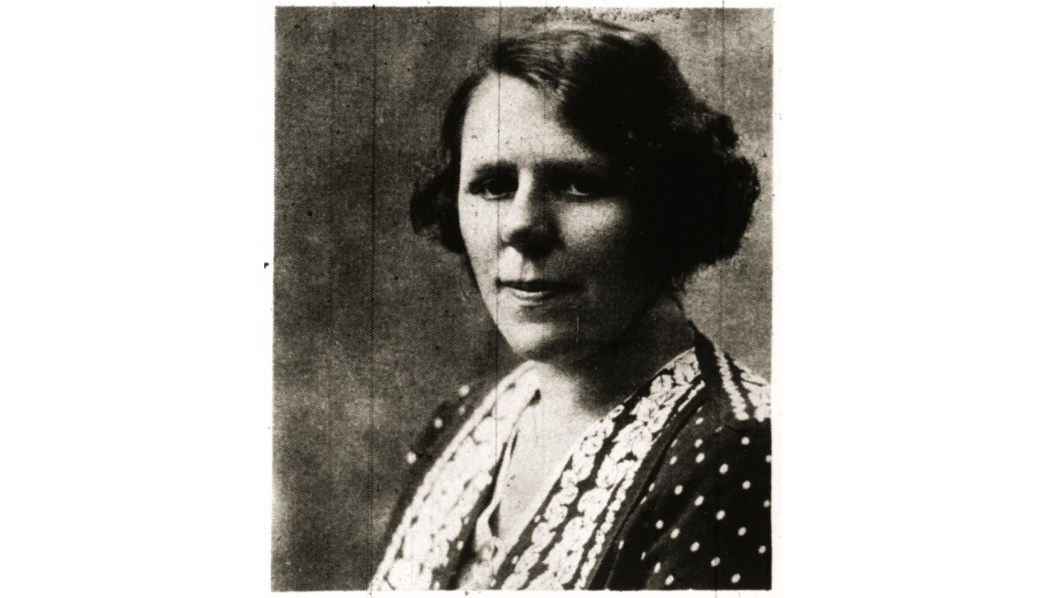

Militant class fighter Stella Petrosky was s a divorced miner’s wife raising eight U.S.-born children facing deportation to Poland after her arrest for activity with the Wilkes-Barre Unemployment Councils.

‘A Dangerous Woman: The Story of Courageous Stella Petrovsky’ by Martha Kieth from Working Woman. Vol. 6 No. 7. August, 1935.

According to the “best people” of Wilkes-Barre, Pa., there is a “dangerous woman” at large. Stella Petrosky is her name. Wife of a coal miner, mother of eight American-born youngsters, this tall strong, blond woman of 36 faces deportation to Poland.

What makes her “dangerous?” Why is the American government anxious to send her out of the country? The following short story of her life will give workers a good idea of what Stella Petrovsky has done to merit the close attention of our so-called “guardians of law and order.”

STELLA and her daughter Alice took part in the first nation-wide unemployed demonstration on March 6, 1930, when over a million and a quarter people from coast to coast demanded more relief. They had their first experience with police terror in Wilkes-Barre. About 75 people assembled but there were more police than people. Before the Chairman’s first sentence, police threw a tear-gas bomb and everyone ran. All were searched for non-existent weapons. Four were arrested but released after questioning.

In spite of this beginning, Stella began to feel that organization was the only hope for help. Things were not well at home. Her husband, Thomas, was drinking pretty heavily. He could see no way out of the poverty of a working miner and became quarrelsome and brutal. The situation grew so bad that Stella began to fear for the effect on the children. She tried to reason with him, to show him that she was not to blame for the rotten conditions and at times he would seem to understand. Then things would grow black again and he would drink himself out of his misery into brutality.

Once when Stella was sick in the hospital, a social worker spoke to her very plainly and urged her to divorce her husband. Even though she did not believe in divorce, she decided to do so for the sake of her children and moved to Wilkes-Barre from the small coal town of Ashley where they had been living.

When there was no longer even meager support for the family, they were forced to take to relief. For many weeks this was less than $5 a week for nine people. There was no other allowance for rent or lights, coal or water. Stella would herself go out to pick coal because she thought it dangerous for the children. It was nearly impossible to feed so many on so little.

Organization Wins Relief

After literally years of starving. Stella heard that the Unemployment Councils, organized in 1933, would help her. There she found out that according to the relief budget she should be getting $10 a week for food. They went with her on a committee and took this up with the board. Her relief was increased at once.

And this was how she got her first ton of coal in the winter-time: when she told the Council that she could not cook without coal and that the relief kept promising but that the coal did not come; the committee got busy. When Stella got home the coal was already in the cellar. Results taught her that organization brings strength. Knowing that her battle was not the only one to be fought, she joined the Council and began helping her neighbors in every way she could.

She helped organize the first “Hunger March” which demanded increases in relief, coal, milk, shoes. Her children and hundreds of others marched as they were, bare-footed, carrying empty milk bottles. The Times Leader of July 3, 1934, reported “100 Children Parade in Blistering Heat; Leaders Secure Audience with Relief Chief.”

Stella’s next activity was a big victory. A family was to be evicted and appealed to the Council. A committee was elected to reason with the owners and a large number of workers gathered at the home where the eviction was to take place. The police arrived and tried to break up the gathering crowd. Clubs were swung right and left and Stella was arrested, getting a bad bruise which still bothers her. The newspapers wrote plenty about the eviction. A committee went to the mayor and insisted that the four who were arrested be released at once. Stella and her daughter Genevieve, were freed with apologies from the mayor for the police brutality and a promise that no further evictions would take place in Wilkes-Barre. The others were released the next morning when a police station packed with workers frightened the Chief. He did not dare send them to jail.

But the people she helped were not the only ones who now took notice of Stella Petrosky. Almost every night the police patrol car would go by and throw its spotlight on her porch. Sometimes a car would stop and, after a while, go on.

Schoolboys Imprisoned

Then the miners’ strike against the Glen Alden Coal Company began. Several schoolboys were sent to jail for a year because they had stones in their pockets. Their fellow students in the G.A.R. High School decided to strike for their release. The strike spread to Dana Street Public School and Stella kept her children out. When she saw police riding on horses, firing into the air to frighten the children into school, she got together with her neighbors and organized a committee to protest to the mayor.

“It is not safe,” she said, “for children to be on the street whether they are going to school or staying home.” The committee was refused admittance but the Chief of Police told them not to worry. Tomorrow there would be more police and more horses! It was on the charge of leading this strike that Stella was later arrested. That was given as the main excuse but there were other charges.

One day in April, as Stella was baking bread and preparing lunch for her children, some men came into the kitchen. They said, “Come with us!” When she wanted to know where and why, they said someone wanted to see her downtown to ask her a few questions. She said the children would be home for lunch soon–would it take long? Oh, no, they said, it will only take a little while, you’ll be back before that. When Stella got into the car, they shoved a paper at her and she knew she was under arrest. She thought she was a citizen because she thought her husband was. They showed her she was not.

She was charged with being an undesirable alien under four specific counts, but especially because she was a “member of an organization affiliated with an organization that believes in the destruction of property and overthrowing the government by violence.” This was a false charge since the since the Councils are not affiliated with any political organization. Held on bail of $1,000, Stella Petrovsky was released only after two nights spent in jail and after the pressure and indignation of her friends reduced the bail to $500, which was paid by a member of the Civil Liberties Union.

At the hearing in her case no defense witnesses were allowed. Irving Schwab acted as her lawyer for the American Committee for Protection of Foreign Born which had taken up her fight.

The hearing was a farce. The first witness, Mr. Henning, Headmaster of the G.A.R. High School testified Stella called the school strike. He declared she said, “Organize! Bomb the houses of kids that don’t strike. Break windows.” Schwab in cross-questioning obtained an admission from Mr. Henning that he had never seen Stella before in his life. The testimony by detectives was of the same stripe.

A Stella Petrovsky Defense Committee was set up to aid in the fight against her deportation. At a conference, there was even testimony from Mrs. McCarthy, local relief administrator. She is herself a widowed mother of six and had received most of Stella’s complaints to the relief bureau. She said: “I come here to show everybody that I, for one, think that Stella Petrosky is a most desirable type of woman to have in this community or any other, and a wonderful mother to her own children and also to the children of many poor miners. She is not a dangerous woman.” During the last two years I have come to admire Stella more and more. She has come before me as many as two or three times a week, bringing cases nobody else would touch with a ten-foot pole. I don’t know what would happen to the children in the mine patches if Stella were deported:”

The final hearing on Stella’s case was on this June 24. The Director of Relief submitted a letter stating how much had been paid Stella’s family and also a letter from the “poor district.” All this was to prove that it would be cheaper if Stella were deported–separated from her children.

The testimony has already been sent to Washington. It is now up to us to send wires and resolution from our organizations and trade unions to bring mass pressure heavily to bear in fighting for Stella’s freedom! Spread far and wide the little pamphlet called “A Dangerous Woman,” which shows how we can stop the Roosevelt Labor Department’s vicious policy of terrorizing and breaking up workers’ families. We must not let Stella Petrosky be deported!

“A Dangerous Woman” by Sprad, 3 cents each; published by the Ameri can Committee for Protection of Foreign Born, 100 Fifth Ave., New York, N.Y.

Stella Petrovsky is an “undesirable alien” according to the bosses in Wilkes-Barre and the Department of Labor is always willing to oblige these gentlemen. If the Department, headed by Frances Perkins, stood for the workers’ interests, it would not be trying to deport this fine woman; fighter for relief; admirable mother; militant, courageous worker. Her eight children need her, American workers and their children need her, and we can still save her from being shipped to fascist Poland where dungeons wait for militant workers.

The Working Woman, ‘A Paper for Working Women, Farm Women, and Working-Class Housewives,’ was first published monthly by the Communist Party USA Central Committee Women’s Department from 1929 to 1935, continuing until 1937. It was the first official English-language paper of a Socialist or Communist Party specifically for women (there had been many independent such papers). At first a newspaper and very much an exponent of ‘Third Period’ politics, it played particular attention to Black women, long invisible in the left press. In addition, the magazine covered home-life, women’s health and women’s history, trade union and unemployment struggles, Party activities, as well poems and short stories. The newspaper became a magazine in 1933, and in late 1935 it was folded into The Woman Today which sought to compete with bourgeois women’s magazines in the Popular Front era. The Woman today published until 1937. During its run editors included Isobel Walker Soule, Elinor Curtis, and Margaret Cowl among others.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/wt/v6n07-aug-1935-WW-R7524-R2.pdf