The ‘Forgotten Famine’ of 1925. Upheaval in the revolution and Civil War, a strike of English landowners, fuel shortages, extreme austerity by the counter-revolutionary Cumann na nGaedheal (modern Fine Gael) which cut farm laborers wages by 16%, and a poor harvest in 1924 all combined with others factors to to create famine conditions in the west of Ireland during 1925.

‘Fighting the Famine in Ireland’ by Robert Stewart from The Daily Worker Magazine. Vol. 2 No. 100. May 9, 1925.

IN 1897 there was a partial famine in Ireland just as there is this year. The English government then acted exactly as the Free State government is acting today. Thru its official press it denied famine and minimized distress. In the house of commons when confronted by the Irish M.Ps. With the names of the people who had died of starvation, Mr. Balfour jocosely asked if the Irish expected him to supply the peasants with champagne. Today Minister McGilligan in the Free State Dail, replying to the labor T.D., admitted that there would be deaths from starvation in Ireland, but added, it was not the business of the Dail to provide work for the people and the sooner they realized this the better.

IT WAS in Mayo during the last big election, and in some of the homes I visited while canvassing, there was no food. Women told me they had not broken their fast that day. The woman showed me a bit of dry bread she was giving to a sick child, and said it had been given hey by a neighbor, and I saw that the sugar bowl was quite empty. Hunger is written on the thin faces of the crowds of unemployed men standing listlessly about the streets. They will tell you “we want work” and turn away ashamed lest you should take them for beggars. Except the professional beggars who follow you around promising prayers, no one asks for alms. The people are very proud and very sensitive, and try to hide their poverty as if it were a disgrace. Only when someone is ill, or when the crying of the children for food becomes too intolerable some woman will burst forth and tell the truth. How they are maintaining existence on the relief that is being given them is a question that I have not been able to solve. Four shilling per week for a widow with seven children! No wonder the children are naked under the outer ragged garment, no wonder consumption is rife.

WHAT makes the danger of the present situation is that the shops also by giving credit have tided the people over many bad years, are themselves in bad straits and are able to give credit no longer. This is the second bad harvest following on the disorganization caused by the war. In Charlestown and Swinford this is plainly evident, if one looks at the empty shelves, and the shop windows filled with dummy boxes and empty bottles, and notes the general air of depression. Many of the shop-keepers are on the verge of bankruptcy, they are going “wallop” in the local expression.

IN Ballina which is one of the most prosperous trading towns of the West and where the depletion of stocks is not so evident, I saw women from the country in shawls, buying tea by the ounce and sugar by the quarter pound, and meal by the pound, and so ashamed and so timid, fearing anyone should notice the tiny marketing, and still more fearful that their credit was outrun and that they would meet with a refusal.

Though the roads are such as to make motor traveling exciting, little is being done to repair them. In some places, however, the Free State government has opened relief works just before the election. Three shilling four pence per day seemed to be the average pay, and compared to the one shilling per day given by the English it looked good; but the rate of living has trebled in Ireland since 1897, and the English gave work six days a week and did not make relief work conditional on belonging to any political organization while the Free State authorities generally only provide two or three days’ work a week and make employment conditional on the man first paying one shilling and joining the Cumann-na-Gael organization. In cases where the man was too poor to pay the one shilling, eggs were taken in lieu of payment to the Free State party fund.

The famine is partial and curiously patchy. It was the same in 1897. In Klllala for instance, and in Ballycastle last year’s potato crop was splendid and farmers have seed to sell in Portacloy, and other places not forty miles distant it has failed completely and the people have been able to sow no seed. The oat crop on which their poultry industry so largely depends was also a failure, and the hens are dying for want of food. Seed oats and seed potatoes are the urgent need if an even worse famine is to be avoided.

After the famine in 1897 fish curing stations were put up at Belderring and others of the worst districts so that the people might salt the fish so plentiful along the coast. Fishing used to be the main industry of the people. Today the fish curing stations are closed. There are no fish. During the Anglo-Irish war and since the Free State came into existence, the English steam trawlers have been allowed to come right into the coast within the prohibited 3-mile area.

With their large nets and powerful engines they have, as the poor fishermen say, “dragged the bottom out of the sea,” in other words, they have destroyed the spawning beds, and now there are no fish, the little fishing boats are idle and the nets have rotted. An inspector of fisheries told me that it would take five years probably for the fishing to recover, even if the English trawlers were now to be kept outside the coastal area. The Free State evidently fears antagonizing their English masters, and makes no effort to protect the fisheries. The Helga, the gunboat used by the English to shell Dublin in 1916, has been taken over by the Free State for the protection of the coast, but the English captain is still retained and it is not likely he will be disagreeable to his own countrymen. An occasional little French fishing boat is caught and fined, but the big English trawlers who are doing all the damage are left in peace to ruin the fishing grounds on which the life of the western seaboard depends. This means that whenever, like this year, there is a partial failure of the potato crop, it means actual famine and people dying of starvation, and amongst the children only the fittest survive. Emigration goes up. The English colonies where conditions are hard, and cheap labor is wanted, profit thereby.

AS I returned in the train from Mayo, at each station I heard the emigrant “keane.” All who travel by the western line know it, and it is hard to forget. It tears one’s very heart out. The crying of the mothers as the train bears off their dearest to foreign slavery, the shrill cry of the old people who know they will never see the bright boys and girls who are going again, the “keane” echoes right along the line as the train steams away, to be taken up at the next station where more emigrants are waiting. The emigrant “keane” which had almost ceased during the war when the republic brought hope to the people, is echoing wildly again thru the Free State.

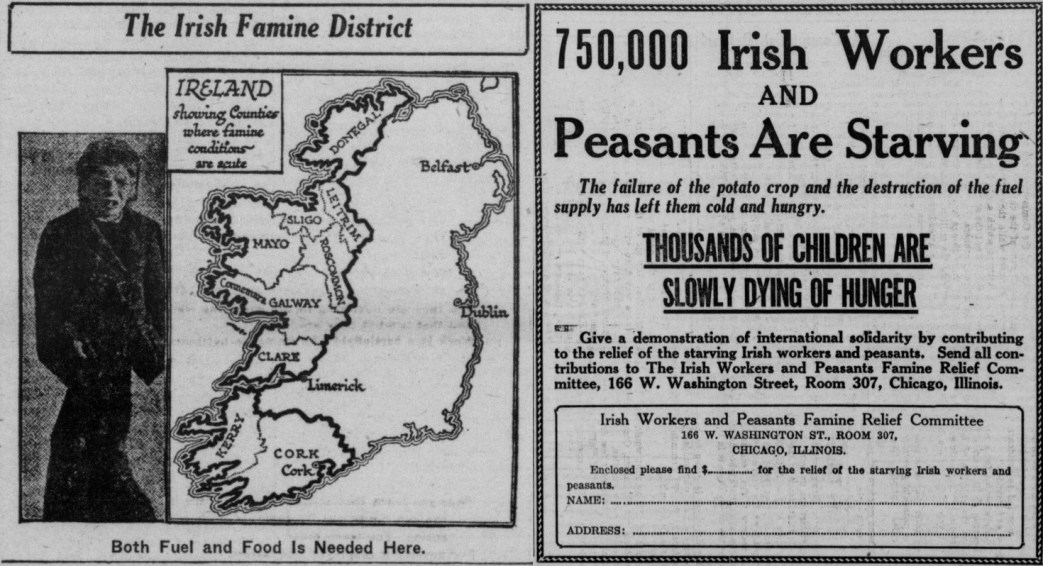

At the Workers’ International Relief committee I have seen letters telling of the conditions in Donegal, letters from people like P. Gallagher of Dungloe (Paddy McCope) from which it is evident that things are quite as bad there as in Mayo. Col. O’Callaghan Westhropp’s statement at the farmers’ congress described alarming conditions in Clare. The Irish Times had an article published from a correspondent contradicting this, but a few days later had to admit everything as far as the wiping out of the cattle and the desperate need of the small farmers.

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1925/1925-ny/v02b-n100-supplement-may-09-1925-DW-LOC.pdf