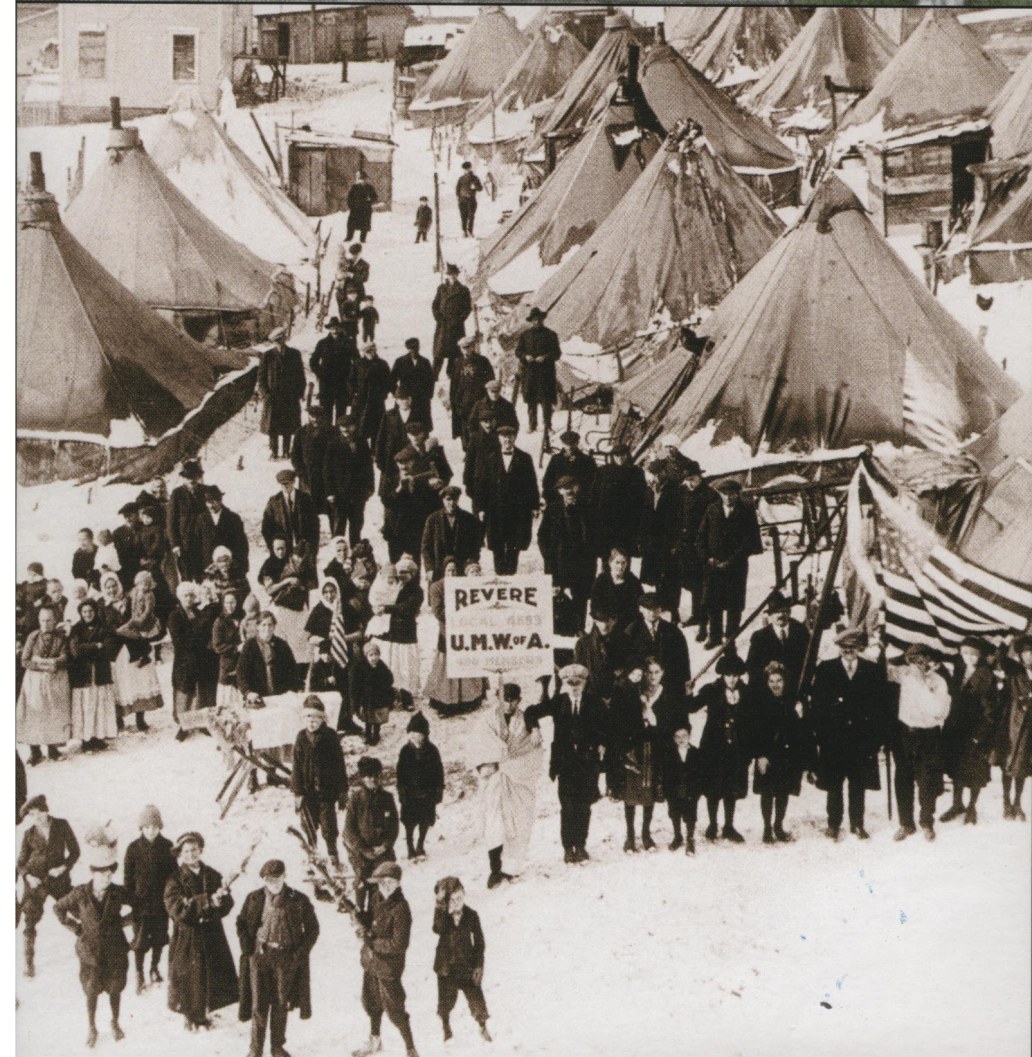

The threat of eviction from company-owned homes was a major weapon of the miner operators in discouraging strikes.

‘Two Hundred Tents for Miners Families Evicted by Operators’ by Art Shields from Truth (Duluth). Vol. 5 No. 21. May 26, 1922.

Cresson, Pa. Two hundred tents now on their way to central Pennsylvania will help in stemming the tide of distress arising out of the dispossession of miners’ houses. This is the first batch of tents the district has found necessary to order since Secretary of War Weeks refused John Brophy’s request for a thousand army tents.

The tents are ordered as a counter to the eviction weapon which is regarded as the most dangerous weapon immediately at the disposal of the operators. This policy of throwing people out of their homes is not so dangerous as in the West Virginia communities however, because the proportion of company-owned houses is not so great in Pennsylvania.

Of the 43,000 miners unionized before the strike hardly more than one-third are supposed to live in company houses. In the late non-union fields of this district, where some 20,000 men have been organized and called on strike, the ratio is higher, ranging up to 50 and 70 percent.

So far nearly 2,000 eviction notices have been served, though only a few hundred families have. actually been vacated. The value of the eviction notice lies rather in its threat than in its execution. Once the miner has been evicted and found other quarters the company’s bolt has been shot.

President Brophy announces that all evicted families can be cared for as fast as they lose their homes. Tents will be used only in extreme cases, as for instance in towns 100 percent company owned, where there is no other place to put them. The men 50 far put out have for the most part been taken in by miners who live in their own homes, and in some cases by sympathetic farmers and in others in halls and outbuildings.

Lawyers for the miners warned fight that housing preparations should be made as there was no legal recourse where miners had signed the usual five-day notice clause. This clause in the lease nullifies the usual 30-day notice rights of Pennsylvania tenants. It was made legal by a joker inserted in some farmer’s legislation more than 20 years ago.

Miners in the nonunion fields say they had no opportunity to read the leases when they were hired and given housing, the company officials telling those who started to read that if they didn’t sign at once they would have to go, but attorneys say this fact does not take away the evicting power of the company. Legal redress is theoretically possible only where women and children are put out with violence or where household belongings are damaged in the summary dumpings out which have been so common.

Evictions have seldom been attempted in the long established union fields an exception being at Bitumin, Center county, where 41 families were put out by the Kettle Creek Mining Co. In general the union operators hesitate to run the risk of permanently-embittering the men with whom they will have to make another working agreement if they fail to win the present fight to end unionism in the coal fields.

Somerset county leads in the eviction program; Cambria and Indiana counties coming next. In these three counties some 20,000 formerly nonunion men have been organized and taken into the strike movement in the drive that began April 1. In Somerset county the leaders in the eviction program have been the Berwind-White and the Consolidation Coal companies, controlled respectively by the Pennsylvania railroad and the Standard Oil. The Berwind people have served about 400 notices and the Consolidation company nearly half as many.

More than 200 families have left their homes in Windber, half of them forcibly ejected and the rest leaving and putting up with friends in spite of a recent company announcement, privately given out, that there would be no more evictions in the next few days. The situation in Windber is unusual; it is such a comparatively large place that there are many independent property owners who are able to absorb the evicted ones, and this readiness of the miners to meet the conditions has halted the company’s action.

Some Windber families who have moved out of company-owned houses after 20 years’ occupancy have uprooted fences and taken down outhouses, in order to leave nothing behind for the company. One sees trucks moving through the streets with household belongings, and the planks and posts of fences, chicken houses and cowsheds.

It is in the smaller places that eviction presses most cruelly places where the company owns everything and eviction means leaving town. Such a place is Ralphton, the Quemahoning mining town, where D.B. Zimmerman is boss, or in the Consolidation village of Jenners. The tents are for such places as these.

Truth emerged from the The Duluth Labor Leader, a weekly English language publication of the Scandinavian local of the Socialist Party in Duluth, Minnesota and began on May Day, 1917 as a Left Wing alternative to the Duluth Labor World. The paper was aligned to both the SP and the IWW leading to the paper being closed down in the first big anti-IWW raids in September, 1917. The paper was reborn as Truth, with the Duluth Scandinavian Socialists joining the Communist Labor Party of America in 1919. Shortly after the editor, Jack Carney, was arrested and convicted of espionage in 1920. Truth continued to publish with a new editor JO Bentall until 1923 as an unofficial paper of the CP.

PDF of full issue: https://www.mnhs.org/newspapers/lccn/sn89081142/1922-05-26/ed-1/seq-1