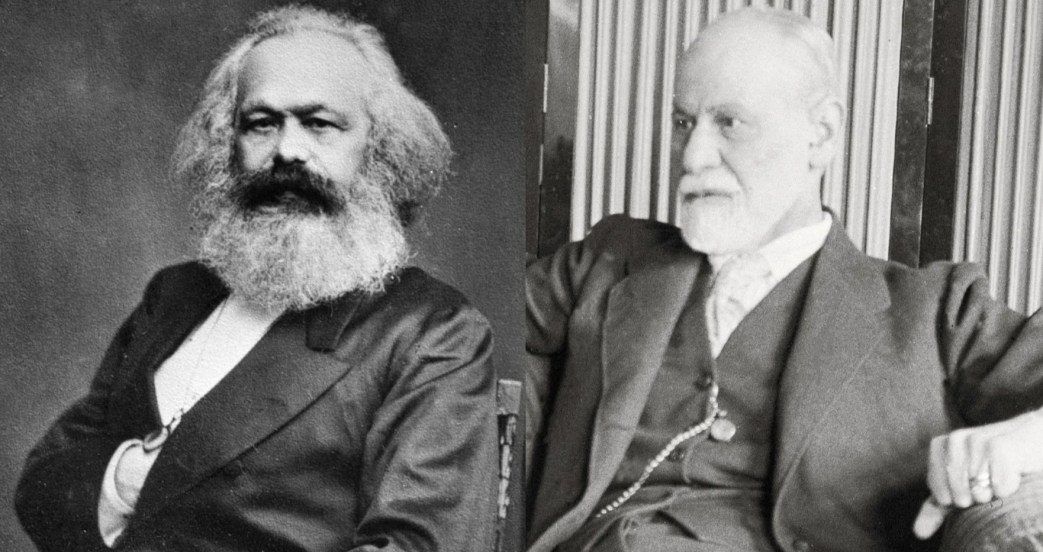

Marxist philosopher Leon Samson weighs in on the perpetual, century-long, leftist discussion of the relationship between Marxism and Freudianism.

‘Freud and Marx’ by Leon Samson from New Masses. Vol. 3 No. 11. March, 1928.

“IN the beginning was the deed,” says Freud, at the end of his little book, Totem and Taboo. Thus also Trotsky concludes his Literature and Revolution. Marxians and Psychoanalysts agree that thought arises from action. This superficial similarity has, however, deceived many people into placing both within the materialistic camp. But to Freud the “deed” is the original crime against the old man of the primitive herd committed by his sons, who, jealous of his monopoly of the women of the herd, killed him and ate him,—out of which is supposed to have come the ambivalence of the emotions of all sons toward all fathers: on the one hand, a desire to kill him, and on the other, a sense of guilt accompanying that desire,—giving rise to the so-called Oedipus Complex. To Marx, on the other hand, the “deed” is equivalent to the mode of production of the material means of life, or the violent revolutionary overturns that transform one mode of production into another,—giving rise to changes in institutions and ideas that constitute the culture of an epoch. Not to see this is to ignore a vital historical difference.

Likewise is it wrong to associate Marx with Freud on the ground that they are both determinists. According to Psychoanalysis the infantile trauma, or the Trauma of Birth (Otto Rank) are said to determine a man by pararlyzing his adult will, so that, frightened by the realities of life, he seeks refuge in the pleasure principle, day-dreaming, the flight to disease, or to his mother’s womb. Marx, on the other hand, shows us the historical springs that determine the positive activity of normal men, living and working as members of a class in well marked epochs of social history. How different this from Freudian determination that deals with isolated individuals thrown out of action by a neurosis.

Marx and Freud have been coupled together because both are said to believe in the doctrine of rationalization, namely that the noble ideals for which men fight in reality conceal their crude, material desires, for food and sex. But when a peasant fights for a farm and calls it liberty, or a worker for a job and calls it socialism, the ideal corresponds quite closely with the reality. The possession of a farm or factory does give substantial liberty to the bourgeois and the “Right to Work,” the negation of Bourgeois liberty, was the first historical slogan of workers fighting for Socialism. When one compares this with the rationalization of over-sexuality by romantic love or of sexual impotence by Platonic love, the analogy is thin indeed.

Although Psychoanalysis can only by a wild stretch of the imagination be placed side by side with Marxism, it can, however, be best understood by the Marxian method.

For example, the theory of sublimation, whereby a Peeping Tom can become a scholar, a sadistic schoolboy a general, an exhibitionist, an actor, or in general, when Cross nurse, or in general, when an abnormal sexual urge is said to be transformable into a normal social activity, it is plain, that the economic relations out of which such activity springs are, in the final analysis, the determining factors in the ultimate biography, not only of the normal man, but also of the neurotic.

The Oedipus Complex, which, (although Freud recently modified it by the Castration Complex) is still held by psychoanalysts as the main source of the neurosis, can be shown by a Marxian Critique to be based upon an historical bubble. The old song of how primitive man roamed about the earth in Cyclopian families headed by jealous sires, who, withholding the women from his still more jealous sons, provoked them to organize sexual revolutions against him,—this song, whose only theoretic foundation is a few stray passages from Plato’s Laws and Darwin’s Descent of Man, is now definitely silenced by an overwhelming mass of evidence as a result of the researches of modern Anthropology. Bachofen, Morgan, Frazer, Hartland, and recently Briffault have clearly proven the priority of the primitive matriarchate. How, then, could the sons have been jealous of a father who had no power? Moreover, it is agreed by practically all responsible Anthropologists that the transition from Matriarchy to Patriarchy takes place historically by the transfer of the mother’s power first to the maternal uncle and finally to the father. The Avunculate phenomenon has been shown to be practically universal. Here the Freudians found a real stumbling block, for, during the rule of the paternal uncle, the father has no power over his sons and therefore they could not have developed an Oedipus Complex against him. Psychoanalysts were at a loss to overcome this difficulty but some of them soon found a way out. Malinowsky, for example, came forward with a theory that the Oedipus Complex takes on a different form in different types of social organization,—that, whereas in genuinely patriarchal societies, the Oedipus Complex is a desire to kill the father and marry the mother, in avunculate societies, it changes into a desire to kill the uncle and marry the sister. This, however, did not satisfy the orthodox Freudians who wished to retain the complex in its pure form, so that one of them, Ernest Jones, originated a still more fantastic theory. “If,” says he, “the sons actually carried out their desire to kill the father, society would have been plunged into bloody wars of mutual extermination. To prevent this calamity, the Oedipus Complex stepped in to cause a change in the social organization. The fathers were saved from the vengeance of the sons by having their power transformed to the maternal uncle. The murder was not carried out, and so the Oedipus Complex remained in the form of a death wish.” Thus Malinowsky would change the Oedipus* Complex: to conform to the Avunculate phenomenon while Jones would have us believe that the Avunculate society itself was a result of the unchanging Oedipus Complex.

All these ingenuous absurdities can be avoided if we consult the real facts of history in the light of Marxian materialism. It will then be found that the earliest social struggles of humanity were indeed struggles against the rising power of the Patriarchs not, however, on account of their sexual monopoly, but because they were the first owners of private property. Patriarchal society rose on the ruins of Primitive Communism and brought with it the first historical antagonism between man and man. The antagonism was economic, not sexual. It was a fight for property. If woman becomes a prize in this fight it is because with the dissolution of primitive communism, she too, becomes private property. The Freudian struggle between fathers and sons for the possession of women is in reality the Marxian struggle between the rulers and the people for the possession of social wealth As for the Collective Unconscious, it will not do to brush it aside with a negative criticism, as the Behaviorists do. The subconscious does exist. It is composed not only of the Freudian anti-social, but primarily of the truly social instincts of man, which have been suppressed by the ruthless discipline of civilized culture.1 In primitive days the conscious and the subconscious are one because man is at one with society. Civilization, through private property, gives birth to the Ego and forces him to war against his fellows. Only Communism can re-establish, on a higher historical plane, the primitive harmony between the individual and society and thus abolish the psychic discord between the conscious and the subconscious, which the psychoanalysts attempt to but never can solve.

The same is true with Adler’s Inferiority Complex. A man’s feeling of inferiority may or may not be based on a real organic deficiency. (Adler does not supply sufficient clinical proof for his theory.) But what really matters is the Will to Power which Adler borrowed from Nietsche and which is the philosophical basis of the Inferiority Complex. But the Will to Power can exist only in a competitive society during which it manifests itself as a struggle to overcome an organic inferiority by substituting for it some form of social superiority. But if Demosthenes is to make up for his speech defect by becoming a orator, or if Napoleon can conquer Europe because he is undersized, types of society must first be assumed in which orators and generals can function. The destiny of the Inferiority Complex is thus determined historically. Today our competitive system may be likened to a chorus in which every singer, urged on by the Will to Power, tries to sing on the top of his voice. Under Communism such chaos is impossible. In its place there is born the now nameless pleasure that all men must feel by each taking his place, however humble, naturally chosen by himself under the functional principle, in a society of harmonious life and work—a society that will thrill by its very perfection everyone who consciously participates in the creation of its social music.

In this epoch of War and Revolution, the psychoanalysts accept bourgeois society and its institutions as normal and offer as their chief cure the re-education and re-adaptation of the abnormal individual to the world about him. Can they not see that a society based on exploitation, slavery and crime is, from the viewpoint of the future, itself abnormal? Why assume that the fundamental passions are wrong and his institutions right? Is it not possible that in the war of the primitive passions against the civilized institutions the institutions themselves might prove historically wrong? The psychoanalyst is fundamentally conservative and reactionary. He assumes that the fundamental instincts of man are antisocial, while his social institutions have a refining influence on them. In this he is mistaken. Marxism throws the burden of proof upon the defenders of family, church, state, stock exchange and battle field. It maintains that the primitive instincts of man are fundamentally sound. Once Communism gives these instincts free play, the reign of the politician, the priest, the philosopher, and their friend, the psychoanalyst, will be at an end.

1. See Holsti, War in Relation to the Origin of the State for a masterly refutation of the primitive war instincts; for an historical proof of the primitive instinct for democracy, hospitality, kindness and sociability see Morgan, Houses and House Life Among the Iriquois Indians. Westermark, Origin and Development of Moral Ideas, and Kropotkin, Mutual Aid.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1928/v03n11-mar-1928-New-Masses.pdf