Albert Barr looks at the exponentially growing oil industry and its increasing dominance, urging a industrial union campaign in what is still the primary fuel of capitalism.

‘Oil and Oil Workers’ by Albert Barr from Industrial Pioneer. Vol. 1 No. 8. September, 1921.

LONG ages before the enslavement of one man by another and longer ages before anything even remotely resembling modern civilization existed, oil was evolving, drop by drop, in old Earth’s chemic depths—evolving, accumulating, awaiting the time when a certain desire of man’s would drive him to seek an assistant to the functioning of the machines he had builded as a result of other desires. Yet the liquid treasure that the ages had stored was not drawn upon until, in the late 50’s of the last century the treasure house was smashed open with a giant steel drill a short distance from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S.A.

Swiftly around the industrial world went the news that crude mineral oil had been found in large but unknown quantity. Every intelligent owner of machines knew not only that a new industry had been born, but also that the way had been opened for rapid and almost unlimited advancement in his own industry; and but a few years elapsed after the finding of oil, before that oil became an industrial necessity.

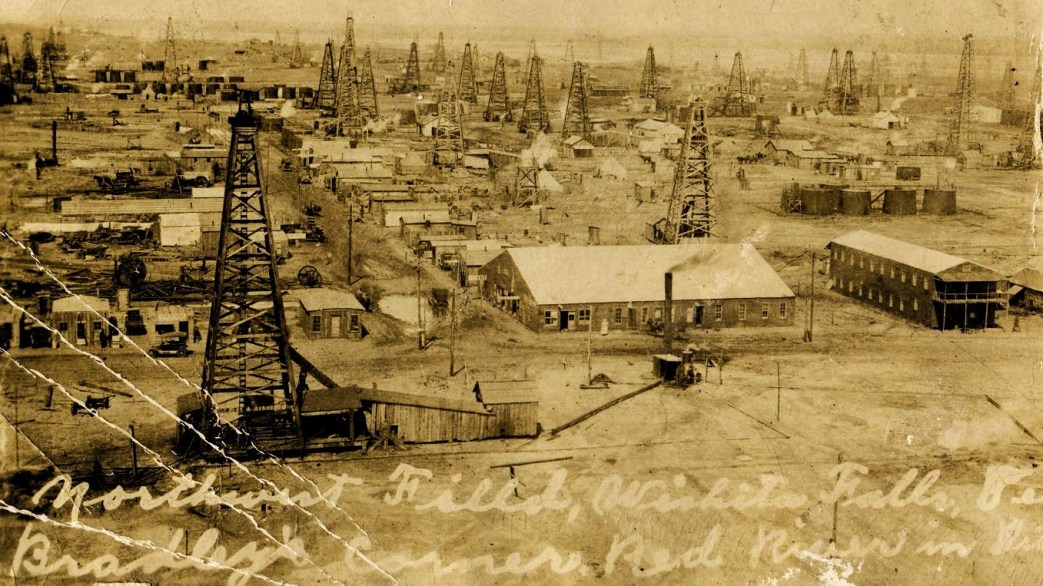

With remarkable swiftness there sprang up in Pennsylvania many “boom” towns inhabited chiefly by men who had money to put into the new industry and men who had nothing but hard muscles and a desire to live. New wells were drilled; new fortunes were made certain; and a new slave group—oil-field workers, sires of those who were to be shot down at Bayonne, of those who were to be mobbed at Tulsa, and of those who were to be sent to Leavenworth from Wichita—was added to that larger slave group—the working class.

The first oil shipped out of Pennsylvania was barreled and floated on barges down the creeks and rivers. In a few years, however, came the pipeline. And the pipeline’s quick coming is typical of the application of improved mechanical methods to oil production. The industry originated lately enough to have profited by all that other industries had been long years in evolving.

From Pennsylvania, the oil industry spread westward across the United States.

With the growth of the industry went the growth of the oil working group of the working class; and with the growth of this oil working group went inter-group specialization of function—one man becoming definitely a driller; another a pipe-liner; another a pumper, and so on. And concomitant with this growth of specialization went what we may call functional clannishness—the hobnobbing of “tankies” with “tankies,” pipe-liners with pipe-liners, etc., etc., each group isolating itself from and treating with contempt all other groups. To be sure, the owners of oil property encouraged this proneness of workers in one line of oil production to treat with contempt the workers in other lines, as it made and still makes for lack of working class solidarity.

As oil production in the United States spread westward, all oil-producing and many other states were dotted with a new kind of industrial plants—drilling rigs, earthen and steel storage tanks, refineries, gas-pumping stations, gasoline plants, etc., etc. As the total production for the United States increased, the number, size and modernity of these plants also increased; and while the total number of oil workers also increased, due to the addition of new fields to already producing fields, improved machinery was displacing men in certain lines of oil production. This displacement of man by machine continues in the oil industry as in all industries.

From the United States the oil industry leaped around the world. For 1918 the figures for oil production (figures compiled by the U. S. Geological Survey) are, in barrels of 42 gallons:

United States–355,928,000

Mexico–63,828,000

Russia–40,456,000

Dutch East Indies–13,285,000

Roumania–8,730,000

India–8,000,000

Persia–7,200,000

Galicia–5,692,000

Peru–2,536,000

Japan and Formosa–2,449,000

Trinidad–2,082,000

Egypt–2,080,000

Argentina–1,321,000

Germany–711,000

Canada–305,000

Venezuela–190,000

Italy–36,000

The figures for total production from 1857 to 1918 in barrels of 42 gallons are:

United States–4,608,572,000

Mexico–285,182,000

Russia–1,873,999,000

Dutch East Indies–188,389,000

Roumania–151,408,000

India–106,162,000

Persia–14,056,000

Galicia–154,051,000

Peru–24,415,000

Japan and Formosa–38,498,000

Trinidad–7,432,000

Egypt–4,849,000

Argentina–4,296,000

Germany–16,664,000

Canada–24,426,000

Venezuela—318,000

Italy–974,000

U.S. figures are limited to quantity marketed.

These figures show that while there has been some changing of places among other countries, the United States has always been easily the greatest producer of crude oil—producing 67.82% of the world’s total in 1918, Mexico coming next with 13.58%; from 1857 to 1918 the United States produced 61.11% of the world’s total; Russia coming next with 24.66%. And from the following table of production for 1919 by fields, in barrels of 42 gallons, it will be seen that the Mid-Continent field is the largest producer in the U.S.

Mid-Continent—196,891,000

California—101,564,000

Appalachian–29,232,000

Gulf–20,568,000

Rocky Mountains–13,584,000

Illinois–12,436,000

Indiana–3,444,000

The growth of oil production in the United States from 500,000-42 gallon barrels in 1860 to 377,719,000 barrels in 1919 followed the demand for oil and more oil, as more industrial uses for oil were found. As exemplifying the fact of the necessity for oil in the present social and industrial scheme, consider the minor fact that the number of officially registered motor cars in the United States for 1921, is 12,000,000. These cars, excepting perhaps one half of one per cent, are driven with gasoline, one of the most important of oil by-products. As exemplifying the anarchy of the present methods of oil production—production for profit—consider the important fact that the Capitol Crude Oil Co. has a refinery—their only refinery—at Santa Paula, Calif., with a total daily capacity of only 40 barrels, while at Bayonne, N.J.—Bayonne, city of evil reputation where the lives of 18 striking oil slaves were ended by company-gunmen’s bullets—The Standard Oil Co. has a refinery with a daily capacity of 88,000 barrels.

On the part of the large oil companies there has been, of course, some striving towards concentration of plants and coordination of working forces; but even so, the waste of effort in the oil industry is notorious.

In 1916-17 the Oil Workers Industrial Union (I.W.W.) carried on a vigorous organizing campaign in the Mid-Continent oil fields. The oil workers responded to the call of the I.W.W. for organization, some thousands joining and remaining in the union. The oil companies expressed their resentment of the I.W.W.’s activity at Tulsa in 1917, by organizing a mob of very law-abiding citizens to beat, tar and feather a group of active I.W.W. oil workers; and in Kansas with the well-known Wichita indictment, on which 26 men were sent to Leavenworth prison for terms ranging from 3 to 9 years. With the last-named atrocity, organization work in the oil fields ceased, unfortunately.

After the signing of the armistice, hundreds of soldier workers went back into the oil industry; the labor market became swollen and the unusual wages paid to oil workers during the war were cut and working conditions became bad.

Now, since the supply of crude oil surely cannot be unlimited; since present methods of oil production are extremely inefficient, and wasteful of oil and energy; and since the great mass of oil workers is unorganized—two things must be done:

The oil workers must be organized industrially; and such plans must be made as will insure rapid and complete concentration of energy in oil production when the oil industry as we know it today crashes in the general—and inevitable—collapse of the capitalistic system of production. Both of these tasks are gigantic and cannot be completed without hard thinking, hard working and hard fighting. Therefore, the sooner and more seriously they are begun, the sooner will they be completed.

The Industrial Pioneer was published monthly by Industrial Workers of the World’s General Executive Board in Chicago from 1921 to 1926 taking over from One Big Union Monthly when its editor, John Sandgren, was replaced for his anti-Communism, alienating the non-Communist majority of IWW. The Industrial Pioneer declined after the 1924 split in the IWW, in part over centralization and adherence to the Red International of Labour Unions (RILU) and ceased in 1926.

Link to PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/industrial-pioneer/Industrial%20Pioneer%20(September%201921).pdf