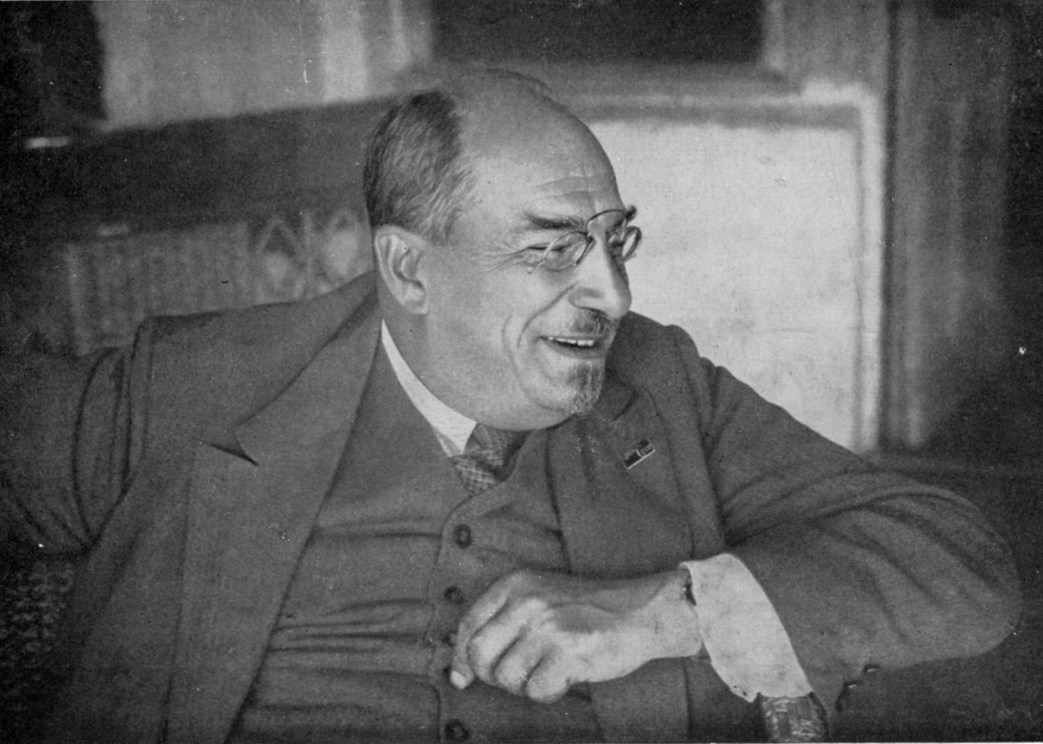

Lunacharsky reacts to the anti-Soviet bias that scuttled the elections of Deborin, Fritsche, and Lukin to the Scientific Academy.

‘The Struggle for the Alliance of Science with Labour’ by Anatoly Lunacharsky from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 9. No. 9. February 22, 1929.

In January of this year there took place the election of new members to the Scientific Academy, increasing the number of academicians from 40 to 80. The candidatures were considered and proposed with the active participation of the scientific workers and institutions of the Soviet Union. After the secret ballot among the old members, it was found that three candidates supported by the whole Soviet public, and chosen almost unanimously as candidates at the public preliminary ballot, had not received the necessary two-thirds majority at the final ballot, which was a secret one. These three candidates were: the philosophic researcher Deborin, well known to the workers both at home and abroad; the literary historian and philologist Fritsche; and the Marxist historian Lukin. The cause of the frustration of the election of these comrades is to be found in the anti-Soviet attitude of a section of the old members of the Academy, and great indignation has been aroused by the cowardly double game played by those academicians, who were unable, at the public ballot, to bring anything against the scientific services of Comrades Déborin, Lukin, and Fritsche, but made use of the secret ballot for an anti-Soviet manoeuvre. Scientific bodies of various kinds passed numerous resolutions demanding the correction of this blunder. An extraordinary session of the Academy, participated in by the newly elected members, decided to request the Soviet Government to agree to the election of the above three comrades by the Plenum of the Academy–without recourse to the preparatory procedure prescribed by the statutes. This agreement has already been given by the Council of People’s Commissaries. The importance of this occurrence is shown in the following article by Comrade Lunatcharsky, taken from the “Isvestia”. For technical reasons the article is here published in abbreviated form. Ed.

The Scientific Academy is the most conservative part of our cultural world. It is no secret that the tsarist government treated the Academy as an extremely privileged institution. It took great care that the Academy was not contaminated by the admission of members with too radical views.

The revolution, in taking over the human and other material belonging to the order which it destroyed, was exceedingly careful to destroy nothing unnecessarily. We saved everything which could possibly be saved. Often enough what we had saved seemed suspicious, seemed to conceal in dubitably disagreeable elements within it, but we said: We shall put this in order later on. The time will come when we are stronger, and will be able to judge what we can take over entirely into the new life, and what we can only take over in part, or after considerable reform. It is better to throw away later what we do not require than to destroy now what we may still need.

With respect to Science the revolution was especially cautious. It is obvious that bourgeois science has been distorted in the interests of the bourgeoisie, and that it rejects such conclusions as Marxism, drawn from the total development of scientific thought. But for our times science without Marxism resembles the world view of the church when it rejected Galileo’s teachings. It is simply a half-science. The proletariat cannot content itself with a science trimmed by bourgeois society to fit its own requirements. I repeat, however, that in this respect we proceeded very cautiously.

We granted the utmost freedom to the scientific workers; we were well aware that here nothing could be attained by force, but only by conviction. On the neutral territory of science we permitted scientific thought to go its own way, hoping that in time this way would merge into new channels under the influence of the stupendous force of attraction exercised by the Marxist way of thinking. We have waited. We have been patient. Lenin said: The worker has his own path to Socialism. The peasant arrives at Socialism along another path–that of the co-operative; the agronomist and the physician have their own paths leading to the great road to Socialism; the scientist too will come to us, if he belongs to the type of the strong and sincere human being naturally impelled to replace uncertain and crippled half-truths by the unshakeable truth of the new view of life. It need not be said that when we observed in the scientific world a decided tendency against us, open strivings to injure us, to lure the vacillating masses by deception into the camp of the bourgeoisie or of reaction, and to influence our youth, we found ourselves obliged to take fairly strong measures.

The Soviet power found that the point had been reached when the Academy, which had received more support from the Soviet power than ever before, must be imparted a more living character, and must be transformed into a real centre for our science.

For this purpose it was necessary to renew its composition, to complement it by a number of new scientific forces, including those of Marxist science, and to establish a closer contact, as far as possible, with that immense scientific and cultural work which is going on in a country being renewed from the bottom upwards.

Undoubtedly the Academy contained a number of members who have informed themselves sufficiently on our work during the last decade, even if they have not arrived at a “hundred per cent” faith in our building up of Socialism. Among these people the measures taken for the revival and reanimation of the Academy found ready support. At the opposite pole, however, there gather the reactionary forces in the academy. They have not liked those academicians who are faithful to the Soviets, and have regarded them almost as traitors, but they have put up with this “treason”, since it has supplied a certain guarantee for the continued existence of the academy, and has brought with it certain material advantages.

This situation has naturally been clearly understood by the government; it has been aware that among these 40 “immortals” class hatred is equally immortal, and often reveals a touch of monarchist colour. The government has been aware that sometimes a great scientific name and valuable purely scientific services may be combined with fossilized views, with the vanity of a scientific mandarin, and with an instinctive antipathy towards the revolution (an antipathy substantiated by a few cheap sophisms). The Soviet public demanded the energetic discussion and settlement of the question of an actual renewal of the Academy, transforming this into a living member of our society.

Thus the election of new academicians and the extension of the number of the members of the Academy was decided upon. The election was organised as publicly as possible. Every scientific and cultural force in the country represented its standpoint. The lists of candidates were drawn up in an atmosphere of widest publicity, and were examined, sifted, and proposed by the academy itself. The statutes gave the academicians the right of secret ballot. Careful preparatory work laid down the lines upon which the renewal of the Academy must be carried out if it was to be effective. The results of the voting in the separate sections left nothing to be wished for. The section of humanist sciences elected all candidates.

The adherents of “moderate academism” may perhaps object that the Academy showed every willingness, that at the last Plenary Session it elected by secret ballot, with an overwhelming majority, the candidates proposed to it, including even a number of Marxists. It reserved to itself only the very small liberty of frustrating the election of one philosopher, one philologist, and one historian. The statutes grant the Plenary Session the right of a final decision by secret ballot.

Such objections as these, by which even representatives of the “centre party” in the Academy attempt to hide the real significance of the above-mentioned facts, must be decisively rejected. The Academy should have realised that the Soviet public, the revolution, sets it very definite conditions. The Academy should have realised that it is being put to the test: to what extent is it capable of standing the somewhat difficult operation of Sovietisation; to what extent is this still possible at all without quite another type of reform the reform which raises the question: how can we build up our scientific world, from the socialist standpoint, without paying regard to any relics of the past which may still exist, but by shattering the whole structure of the past and erecting the edifice of science according to an entirely new plan?

Does the Academy perhaps believe that the Communist Party, the Soviet power, and the people, have not the courage to set aside the Academy and to hand over its material goods to a differently organised scientific institution? Does it believe that its foreign friends are powerful enough to protect the Academy against the “designs” of the Soviet power by either immediate help or “authoritative protest”? Well, if the academicians do believe this, then they have played with fire, and I fear they will burn themselves severely.

The majority of the academicians–it may be replied–have shown themselves entirely loyal. All that was the matter was that the two-thirds majority was not reached. The Presidium of the Academy took immediate steps to avoid prejudicial consequences, etc.

Very true, there is something positive in this. The Academy has been the prey of inner schism brought about by the combined influence of the forces to which it has been exposed. There are some who believe in the Soviet public, and are ready to march forward with it shoulder to shoulder. Others have grasped that if they do not follow this example they will lose the game. But there have been quite a number people who have come forward with open visor–their faces hidden only by the very transparent veil of various formal considerations–in opposition to the correction of the absurdities which have been committed.

To throw dust into the eyes of the Soviet public, to provoke a small scandal under cover of the secret ballot, to meet the Soviet public to the extent of 90 per cent. whilst retaining 10 per cent. as a field of action for their reactionary views–this has indubitably been the politically oppositional idea pursued by a very considerable section of the academicians.

These dignitaries of science have done no more than reject three candidates, and this only at the last secret ballot, entirely without responsibility, whereby some of them altered their standpoint again a few days later.

But every candidate proposed by public opinion is a necessary part of the future work of the Academy. Tact alone demanded that the Academy should comply with this categorical demand made by public opinion. The academicians have desired to oppose their formal right to liberty to the public opinion of the Soviet Union.

If they have done so, they will find themselves in contact with the flame of revolution, and this may lead to a very painful burn.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecor” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecor’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecor, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1929/v09n09-feb-22-1929-inprecor.pdf