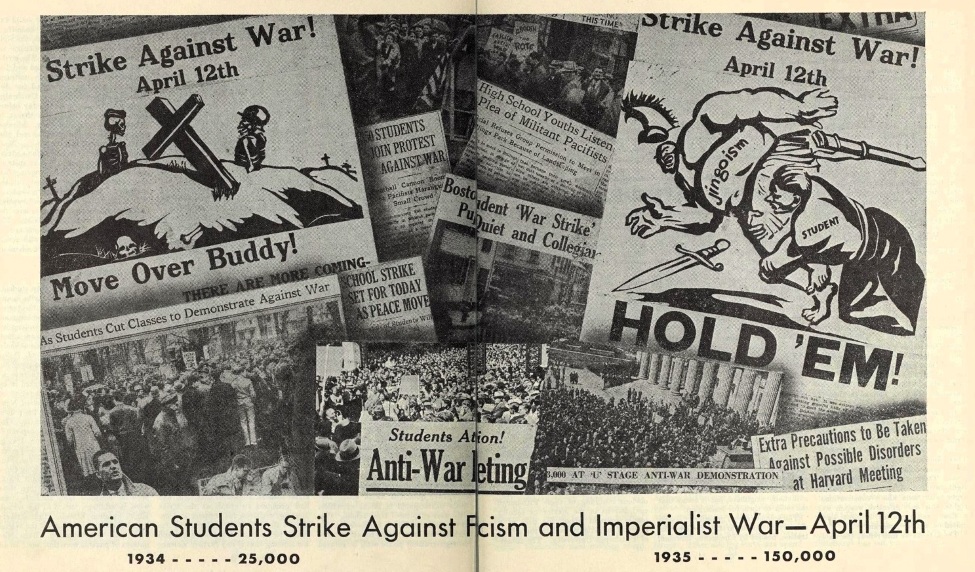

The hammer comes down on student activists as campus repression follows 1935’s mass anti-war strikes. Reports from around the country.

‘The War-Makers Strike Back’ by Jean Horie from Student Review (N.S.L.). Vol. 4 No. 5. May, 1935.

Scarcely a campus in the country escaped some aspect of the wide-spread drive of suppression against the April 12 Strike. Suspensions, expulsions, arrests, physical torture, organized counter-demonstrations, all testify to the bitter struggles which surrounded the victorious anti-war demonstration. Several thick volumes could not contain all the details of this battle. High school after high school, college after college could be listed, where administrations, local police, American Legion Branches, Hearst newspapers, and campus vigilante bands united for a drive against the student anti-war movement unprecedented in open violence and brutality. If we examine a few of the major cases of terror against the strike, we soon see that there are certain similarities. in all the attacks.

California

In California, weeks before the strike, school administrations were lining up student vigilante bands, who patrolled the campuses of the University of California and the Los Angeles Junior College watching for strike leaflets to confiscate. Students distributing leaflets were called in by the administrations. The colleges and high schools were surrounded by plainclothesmen and Hearst reporters. The Hearst press headlines ridiculed the strike and warned citizens of subversion in the schools. As strike preparations continued to spread, the attacks sharpened. 18 Berkeley students were arrested for distributing anti-war literature. In Pasadena, two girls were picked up for hanging anti-war posters. Margot Lamb of Los Angeles Junior College was arrested for distributing leaflets. Bernice Gallaher of John Marshall High and Harold Breger of Fairfax High were suspended from school until they would promise to stop anti-war activity. Strike preparations gained ‘ momentum with each new attack. A thousand students at the University of California in Los Angeles poured out of their classes on April 12 and conducted an orderly strike meeting on the campus. At Pasadena, the school band stood by to protect the successful strike of 500 students. It was in the high schools of Los Angeles that the day of April 12 was marked by most violent suppression. All schools were surrounded by cordons of police. The strike leader at John Marshall High was physically removed from the campus. Class schedules were changed at Fairfax High to keep students in the rooms. Two hundred police at Roosevelt High seized strike leaders and penned hundreds of striking students in the building. The principal of Belmont High hastily called a Peace Assembly. Two thousand students of Los Angeles Junior College, crowding the campus for their strike meeting, heard popular tunes played by a huge amplifier that had been shunted toward the meeting. At the same time, Director Ingalls of the college administration appeared on the scene tooting a whistle to marshall the vigilantes into action. Still the strike meeting continued uninterrupted. Squads of police flooded the campus. Students were pushed, knocked down, kicked, beaten into unconsciousness with blackjacks. The shout, “police off the campus” gained momentum as students charged the cops and drove them from the meeting. The strike demonstration continued successfully. Later in the day, Ingalls ordered four suspensions, Hans Hoffman, Margot Lamb, Kenneth Jampoul, and Eugene Droginsky.

Chicago

Chicago strikers were attacked with a violence in many cases equaling the brutality of Hitler’s methods. Students who distributed strike leaflets at Crane High school were called to the office of the administration. When they refused to answer questions as to which students participated in strike activities, they were suspended from school. One of the students, Lester Schlossberg, was turned over to a “flying squad” of student government police after he refused to answer to the administration’s grilling. The vigilante student group, with the knowledge and sanction of the administration, took Schlossberg to the engine room of the school and applied torture to force answers to the administration’s questions. They put pins under his fingernails, punched him in the face and body, beat him with a heavy rope and tied a noose around his neck in a threat to lynch him. Next day another strike leaflet was issued, Again the students who distributed it were dragged to the engine room and beaten by the “flying squad.” A third strike leaflet was issued. This time, with the sanction of the administration, the strike leaders were taken out of school and beaten. Later that afternoon, as Schlossberg was leaving school, he was again attacked and then suspended. Abe Held, President of the Open Forum Club of Medill Junior College, was suspended for refusing to turn over his leaflets to the administration. Two students of Wright Junior College were arrested for distributing strike leaflets. One of them, Art Rodrequez was suspended from school and two other students were placed on probation. Suspensions and expulsions were threatened at Tuley High School. Police surrounded all the Chicago schools on the day of the strike. Exits were barricaded. Five students were arrested at Wright Junior College and at a branch of Tuley High school over 40 students who walked out were suspended.

New England

Attacks on the strike in New England developed most sharply at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where, a week before April 12, Robert Landay, one of the strike leaders, was kidnapped by a group of R.O.T.C. men. They shaved his head and beat him. Then they entered the dormitory rooms of strike leaders and destroyed their books and papers. A few days before the strike, they kidnapped and beat several other strike leaders. President Compton, who had promised to speak at the strike meeting, withdrew his support and endorsed the R.O.T.C. vigilantes by refusing to take action against them and announcing that if any further violence took place on the campus he would expel all members of the strike committee. On the night before the strike, the vigilantes hauled the fascist swastika to the top of school flagpoles. The strike meeting next day was attacked and disrupted by RO.T.C. men in uniform. Eight students were arrested for distributing strike leaflets to Cambridge High school students on the day before the strike. At Harvard, a threat to kidnap the strike leader was defeated by an all-night watch of several students who moved into his room. Next day 3600 students gathered for a strike which continued successfully in spite of a counter-demonstration, directing fascist salutes and angry shouts at the strikers. Boston Superintendent of Schools Campbell called a joint meeting of school officials and police to meet the emergency of the student strike. The city “red squad” was put on special duty. Campbell threatened with severe penalties any student who left school on April 12.

New York City

Over 40,000 New York City students participated in the largest strike in any one area. It was here that the terror in high schools was most widespread. Attempts at suppression began long before the strike, when exams were scheduled for April 12 in most of the schools. Strike preparations continued. Police surrounded the high schools on April 12. Several hundred striking students at James Madison High were locked in by police and monitors. A delegation of speakers and parents was arrested. Newtown High students, fighting the police, managed to hold a strike meeting. One student was expelled and five suspended. Monroe, Morris, Washington Irving, and Stuyvesant High schools held meetings after battles with the police. Students were kept in the buildings by force at Eastern District and Bryant Park. Fire engines were ready to turn their hose on Erasmus Hall students, who were, in addition, locked in the school. Eight hundred Lincoln High strikers were refused readmission to the school after their demonstration. Even delegations of parents were shut out. In all parts of the city, the number of arrests and suspensions of high school strikers reaches a staggering total. At Hunter College, where a strike of 2200 students was led by 17 campus organizations, including all the publications and the Junior and Senior classes, the administration banned the campus Peace Council before the strike and suspended two of its officers, Millie Futterman and Theresa Levin. On the day before the strike, President Colligan issued to every student a statement condemning the strike. Following the tremendous walk-out, Lillian Dropkin, Chairman of the Strike Committee, Margaret Wechsler, President of the Upper Junior Class, and Jean Horie, Editor of the Year Book were suspended, bringing the total number of suspensions to six, including the freshman anti-war leader, Beatrice Shapiro, debarred several weeks before the strike.

Why These Attacks?

What was identical in all the attacks on the strike was the array of forces. School administrations in all parts of the country worked hand in hand with police and small bands of student vigilantes, often recruited from the R.O.T.C., to terrorize and disrupt the demonstrations. In the light of this suppression, the tremendous total of striking students gains added significance. The campus walk-outs represented concrete victories over the active opposition of these exponents of war and fascism in the schools. The strikes gave us a taste of what the student anti-war movement will have to face in time of war.

We saw that our administrations interests are so inexorably linked with the war-makers on our Boards of Trustees that they were driven to stop our anti-war activity at any cost. They did not hesitate to disregard our alleged rights to free speech and press. Theirs were the methods of outright fascism. We could not quietly argue with them about constitutional rights. Our only effective weapon was a firm, well-organized student body united on a clear program.

The attacks we met reflect the whole wave of reaction in America, initiated by the representatives of Capitalism, striving for the preservation of profits in the face of an ever-deepening economic crisis, fighting for existence in the midst of wide-spread unemployment and misery, seeking to suppress all who oppose the imperialist war they are rapidly preparing. Heralded by Hearst, the drive toward fascism found concrete expression in the brutal attempts to smash our April 12 strike.

Where strikes were solidly organized, where the terror was prepared for and faced firmly, the actions were tremendously successful. Disrupters were isolated. Administrations were forced to cease disciplinary measures. Police were driven off the campuses, With the lesson clear in their minds that a solid organization can defeat terror, strike meetings all over the country endorsed permanent anti-war committees in each school—and an anti-war congress in the Fall to consolidate the whole student front against the increasing attacks in our anti-war activity. Our response to the terror on April 12 was a strike over five times the size of last year’s. Our answer to threats of future opposition will be the broadening and strengthening of all our forces for the fight that faces us.

Emerging from the 1931 free speech struggle at City College of New York, the National Student League was founded in early 1932 during a rising student movement by Communist Party activists. The N.S.L. organized from High School on and would be the main C.P.-led student organization through the early 1930s. Publishing ‘Student Review’, the League grew to thousands of members and had a focus on anti-imperialism/anti-militarism, student welfare, workers’ organizing, and free speech. Eventually with the Popular Front the N.S.L. would merge with its main competitor, the Socialist Party’s Student League for Industrial Democracy in 1935 to form the American Student Union.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/student-review_1935-05_4_5/student-review_1935-05_4_5.pdf