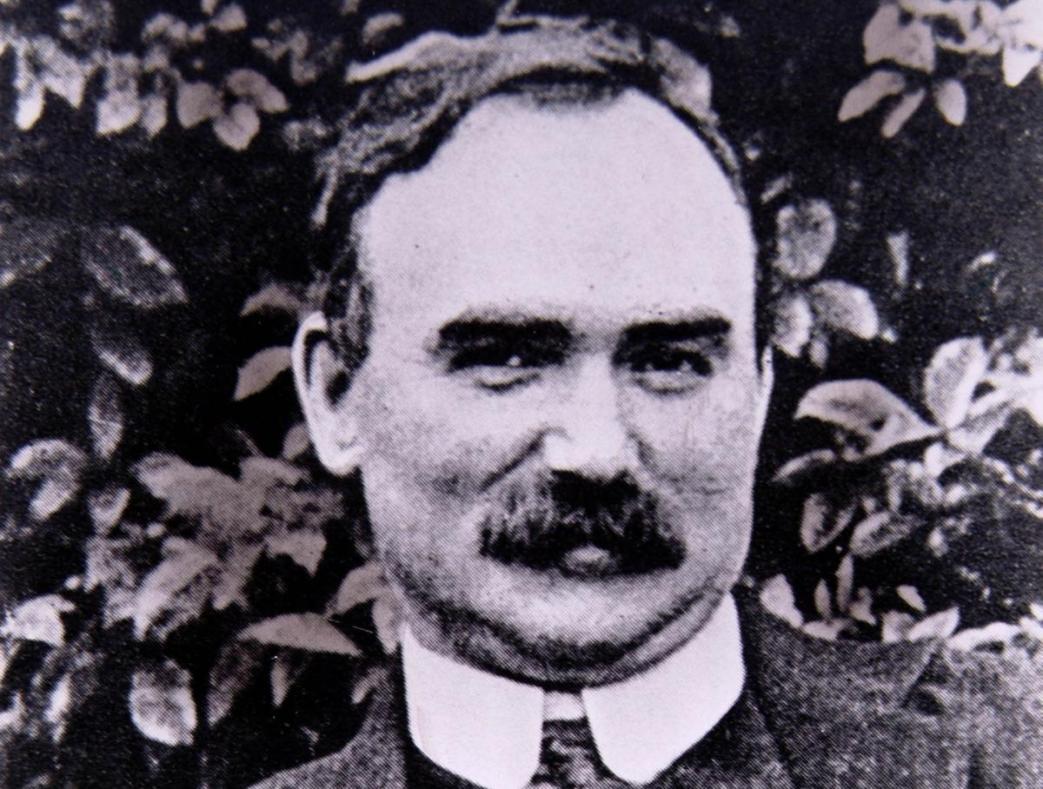

A wonderful essay published 100 years ago today, T.A. Jackson, who met and was inspired by Connolly, seeks to rescue him from the misconceptions about his role and politics already rampant less than a decade after his execution.

‘James Connolly—In Memoriam’ by T.A. Jackson from the Daily Worker Magazine. Vol. 2 No. 89. April 25, 1925.

“The working class can only think and speak in language as hard and definite as its life. We have no room for illusions in our struggle, least of all for illusions about freedom.” James Connolly, July 31, 1915.

WHATEVER it may mean elsewhere and otherwise, “Easter Week” in Ireland is fixed and sacred to the memory of James Connolly and the “men of 1916.” So much so that there grows a danger one that Connolly himself would have been the first and fiercest to revolt against- the danger that he himself will be lost in the devotions paid to his corpse.

JAMES CONNOLLY was more than the commandant-general of the forces of the Irish Republic. For the firmness and thoroughness of his nationalist faith his end speaks unanswerably. His whole life testifies to the equal force and virility of his internationalism.

He who would explain Connolly must be able to unriddle the paradox–“How came the first and greatest leader of working class internationalism in Ireland to be the last and greatest leader of an Irish nationalist rebellion against the British crown and empire?”

THAT the Irish common people should be passionately nationalist was inevitable from their history.

When the Norman invaders first passed over from England to begin the process of “extirpating vice” and establishing the supremacy of holy mother church–with incidental “pickings” for themselves and their overlords the kings of England–there clashed, not two armies of differing speech and descent, but two distinct and incompatible social systems.

EVERY step in the establishment of British rule in Ireland meant to the conquered, not merely the temporarily physical losses of defeat, conquest and dispossession. It meant the destruction of everything traditional and sacred in Irish social existence.

The Irish clans could only survive as clans in the teeth of perpetual war and ravage. Inevitably to be “Irish” meant to be “poor, miserable, hunted and outcast.” The Irish survived as a peasantry tolerated because they were too poor to be worth disturbing–except so far as their very poverty combined with the inaccessibility of the hills and the bogs to which they were driven, had by driving them to live as plunderers of the plunderers provoked reprisals.

To be born of the poorer peasantry in Ireland at any time between 1600 and 1916 was of necessity to be born into a tradition-they are Connolly’s own words–of “stubborn physical resistance to the forces of Britain.” And this was intensified through every generation from the peasants’ rising of 1798, through the Tithe war, the Black famine, and the Fenian days to culminate in the bitterness and fury of the land war of the ’80’s.

To be so born was to have added to all the other incentives to rebellion incidental to a worker’s life, a tradition, not merely of revolt, but of the fact that even defeat could be borne, recovered from and avenged.

James Connolly was born in County Monaghan, in 1870, of peasant ancestry.

BUT it would be folly to attempt to explain James Connolly–one of the least emotional of men–in terms of personal psychology and heredity wholly.

Had he been a nationalist born and nothing more, he would never have returned to Ireland in 1896 with the express and avowed object of founding an Irish socialist movement.

CONNOLLY was above everything a proletarian. His Irish birth and breeding and his knowledge of Irish men and things made it easier for him to organize Irishmen and deal with Irish politics than another. But that he should want to organize the Irish workers, and into an Irish socialist republican party, came from his proletarian instincts and his training in the working class movement.

And both as a socialist theoretician and as a practical Irishman (and hereditary rebel) he saw from the first the need to organize the Irish workers on Irish soil, since they alone could grapple with Irish problems as Irish historical development had forced them forward for solution.

THE natural revulsion of an Englishman–not too far gone in sin–at reading the history of the British empire is one of shame, disgust, and pity for the victims.

The shame is soon shed; since it is that of others. The nausea passes. But the pity abides. And that is possibly the worst that could happen.

Connolly could not have lived ten days in Britain without meeting “pity for Ireland.” You or I can walk into the street, now, and find quite a lot of “pity” for the Indians, the Egyptians and so on. And when the industrial development of Britain was in such a stage that British factory lords and financiers had no use for either Ireland, India or Egypt, except as milch kine from which to draw sustenance for their home industries, pity was, possibly, as much as could then be placed upon the order of the day.

BUT that day has passed and Connolly saw clearly that a new era had come and seeing it, hated with all his splendid power of hate the Irish politicians who, at Westminster, had no other song to sing than of the woes of their “distressful country.”

He saw that the very need to get cheaper and ever cheaper raw materials for the expanding manufactures of Britain had done two things–not only in Ireland, but elsewhere.

It had crushed the peasantry down to the level of a proletariat, and it had made possible the development, on their backs, and at their expense, of a native small-capitalist class who in time, with British surplus capital, would grow into a native capitalism even more rapacious (if possible) than the alien capitalism had been.

SEEING that, he saw, too, that while this native small-capitalist class would be (for sound fiscal and other reasons) even more violently nationalist than the common mass–nationalist from ingrained tradition–they would in equal measure be the first to flinch from a fight which entailed arming the common mass against the “common enemy.”

For, at long last, whatever his nationality or nationalism, the capitalist is–a capitalist. The native, Irish capitalist was willing enough to be freed from his English exploiter and rival. But when the price of that release was to run the risk of placing himself at the mercy of his proletarian fellow-countrymen he, “with one consent, began to make excuses.”

GO over the history of Irish revolts–1798, 1803, 1848, 1867–everywhere there is to be detected, if one reads aright, the same symptom. Always the moral is that of the old piper in Tom Burke “curses on the gentlemen: they always betrayed us.”

Go over the more modern history of India and Egypt–go over the history of Easter week, 1916. The lesson ‘s no different.

WHEN the chance came in 1914 to arm a body of working class volunteers Connolly was glad to seize it. He of all men had “no Illusions about freedom”—none about the power and relentlessness of the British empire.

He seized the chance, first, because before him, too plain to be missed, was the chance to put the Dublin workers on something of an equality with the police guards of the strike-smashing Murphys. Secondly, because he saw (as no man else in Ireland) that only the working masses could be trusted to put up a fight even for so limited a thing as a democratic Irish republic—that the strength of the volunteers was in the workers.

And there was yet another motive soon to become actively operative.

• • •

WHEN the war came, it is not too much to say that to one of the “old guard” of Marxism, in the English speaking world (as Connolly was) it seemed as though the end of every hope had come. Only slowly did such as he recover from the horror that came with the realization that the world army of social democracy had melted overnight, leaving behind nothing but “leaders” serving their kings and kaisers, and the masses disorganized into mobs drifting every whither “as sheep having no shepherd.”

As the horror of shame and disgust was replaced by the horrors of war, so there grew, even with the sound of the guns and the tales of the slaughter, the sense that the masses were regathering—however blindly; that there was a chance that the right lead at the right time might be the spark to explode their stored-up wrath.

FROM the first day of the war, when he had decorated his headquarters with the legend–all across the front of the building–“We serve neither king nor kaiser; but Ireland!” Connolly had grown fiercer and more impatient.

He pressed ever closer his relations with the more ardent among the republican volunteers. He won his way by the sheer compulsion of his command of the technique of the business, until he stood high in the inner councils of those ready to risk all upon the chance that “England’s difficulty was Ireland’s opportunity.”

IT is known now that it was he, more than any other, who had urged on the rising; that when at the eleventh hour MacNeil cancelled the order for mobilization, which was the agreed signal for the volunteers of all Ireland, it was he who insisted, backed by Pearse, in going forward whatever betide.

It is told how he said as he marched out–without emotion or display, in his natural matter-of-fact tone, talking to an intimate–that he knew he was going to his death.

Is there any explanation–to those who knew him–other than this: that his whole being was filled with the desire to strike such a blow as might even by a change rouse the revolutionary explosion which would lay capitalism, its wars, subjections and exploitations, conquered beneath the feet of the workers of the world?

AND how far was he wrong?

He had said that with 1,500 men he could take and hold Dublin for long enough for all Ireland to rise, with half that number he held it for a week.

Only twelve months after he had fallen before the firing squad the Russian masses stirred, czardom crashed, and the Russian workers-revolution had begun.

• • .

IMPATIENT? perhaps. Duped, in spite of himself, by national conceit?

Neither of these. His heart was with the working mass, and he scorned to live safely while they were passing through the torments of hell. He took his chance, knowing it was a chance. He fought for Ireland. But he lived, fought and died that the workers of the world might rule.

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1925/1925-ny/v02b-n089-supplement-apr-25-1925-DW-LOC.pdf